The Kheer Bhawani festival starts Monday in Kashmir. But the Hindu Pandits who celebrate it are still mostly in exile from violence. Can they truly return? Do they even want to? A deep look at Kashmir’s dilemma

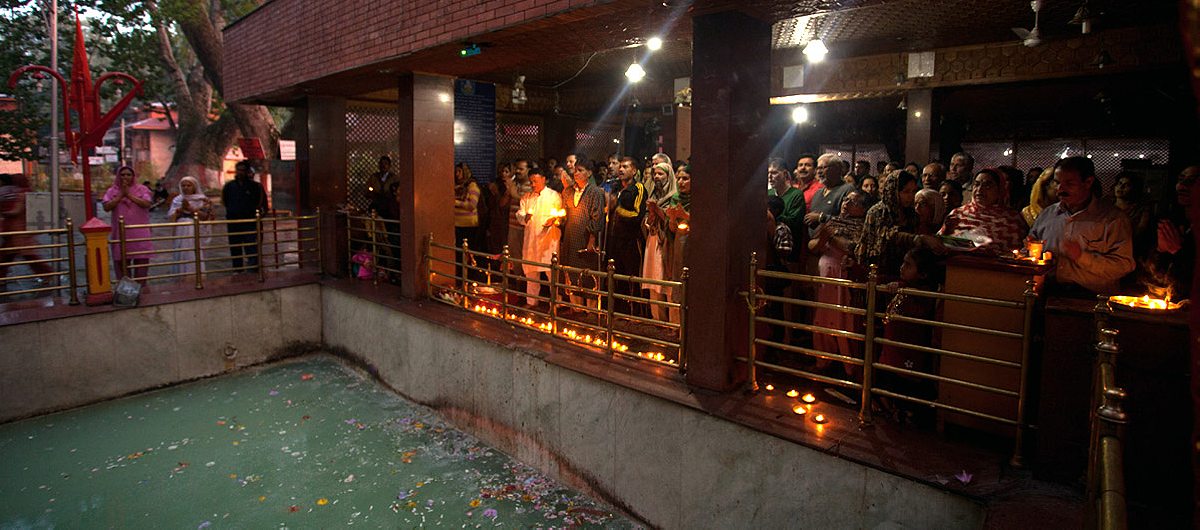

On a night in late May last year, the buses arrived from Jammu, a white flood of headlights rushing by vacant paddy fields. When, at four A.M., I woke to the muezzin’s low, reverberant prayer, they were still coming. They did not slow. The annual festival at Kheer Bhawani, a temple on the outskirts of Srinagar, in the Kashmir Valley, has historically been the world’s largest gathering of Kashmiri Hindus, or Pandits, as they are called. The Pandits believe that the spring on which this shrine to the goddess was built changes its color as a forewarning; at the height of violence in the region, they say, the water was black.

Outside the temple gates, worshippers were bathing in the cold stream. Local Muslims had erected stalls and were selling devotional literature and offerings. Beyond them, a barrage of muddled footwear and a few unsmiling men, the keepers of the shoes. Thousands of barefooted Pandits had overtaken the holy place and were spread out on blankets, picnicking, napping. A man burst into ecstatic song before the deity in her pool, its color obscured by flower petals, and was answered by a congregation of voices and a tabla. Police officers stood watch; volunteer workers dispensed chai and rice. The air was cool and the sanctum shaded, overhung by old chinar trees. A teenage girl pointed upward at a patch of sky delineated by the leaves. “Its shape is India,” she said, and she was right: the country, in pale blue, was floating above us.

In 1994, just a few years after the Pandits left the valley in a mass exodus, a couple of hundred devotees attended the festival. Last summer, over the three days of observance, somewhere near 25,000 Pandits passed through the temple complex. Everywhere there were banners welcoming the pilgrims. This year, the festival will begin on June 17 and if anything, there could be even more worshippers.

The questions that arise this year are the same that were posed last year and the year before: Does this swelling pilgrimage suggest the possibility of a lasting return of the Pandits to the valley? Even if it does not, how to begin to integrate the many thousands of Pandit tourists who used to call this place “motherland”? These may seem obscure, but New Delhi has a clear stake in Kashmir’s rehabilitation and the Pandits are central to any discussion of regional stability. A Pandit presence in the valley is a powerful indicator of normalcy; a placated Pandit community, even one that has no intention of coming back, would restore faith in the region nationally and globally. It would reaffirm India as an integrated democracy. And India knows this.

You’ll notice, as you move through the Kashmir Valley, that fertile strath that cuts between the Greater Himalayas and the more humble Pir Panjal mountain range, whole neighborhoods of empty, deteriorated houses. The window frames are charred black cutouts and the roofs collapsed; the bricks have fused together into vast blocks of sand. Some houses aren’t houses at all, but single ragged walls. There are houses with open cavities like from the swing of a wrecking ball, so you can see the dusty nothingness inside. Children with book bags run between the half-buildings on their way to school, impervious to the ruin.

For centuries, and all through the brutality and bloodshed of British India’s partition, the valley was an improbable bastion of tolerance. Kashmir’s Muslim majority and the Pandits, its upper-caste Hindu minority, lived peaceably in the same districts. The Kashmiri Hindus were closer in culture to their Muslim counterparts than they were even to Hindus outside the India-administered valley. They shared rituals of food and song, certain sacred sites; they spoke the same language; they were physically indistinguishable. While shooting abandoned Pandit homes for this story, photographer Abid Bhat was twice asked by passersby if he is a Kashmiri Hindu. He is not. But there is nothing in his face or his speech to identify him. The only clue is his Muslim name.

Portions of Kashmir are claimed by India and Pakistan both, and have been since the simultaneous birth of those nations. The state of Jammu and Kashmir, of which the fabled valley is a part, was never especially happy under Indian control, preferring independence. But Indian Kashmir was relatively tranquil until the start of a separatist rebellion in late 1989. The uprising was funded partly by Pakistan, fueled by Kashmiri nationalism and mounted by local youth consumed by some notion of azadi, or freedom. The Pandits were early targets of this insurrection. There are stories of mosques that began to blare anti-Hindu rhetoric by loudspeaker and of public hit lists bearing Pandit names. By government records, a couple of hundred Kashmiri Hindus were murdered by Islamic militants—a small percentage of the 60,000 or so people, most of them Muslims, who died during the insurgency, but a number high enough to rain fear on the community.

Anil Saproo was born in the valley in a five-story house bounded by fruit and walnut orchards. In the spring of 1990, when he was six, his father was shot twice and killed by militants. The following day, the body was cremated; afterwards, at dark, the family took a bus to the sanctuary of the Hindu temple town of Jammu, some 300 kilometers, and a drive of seven or eight hours, south. That year Anil’s relatives were joined in sudden flight by over a quarter-million—and by some counts 400,000—Pandits for whom the threat of the militancy had become a given of daily life. The migrants imagined that they would be back in a matter of months. Years passed. No one returned.

Most facts of the migration are contested. Was the exodus purely volitional or of urgent necessity? Even some among the Pandits who went seem unsure. Despite what is printed by Pandit nationalist groups, there was no Pandit genocide. No one was forced into exile, as evidenced by the few Kashmiri Hindus who remained in the valley. Many Kashmiris believe that any Pandit assassinated was an agent of India. And many insist that the administration of the day had a hand in the Pandits’ leaving, that it ushered them out on buses in the night—for how else could they have defied valley-wide curfews? It is commonly thought that the government engineered the migration to malign the separatist movement. Jag Mohan Malhotra, governor of the state at that time, has denied the existence of any widespread effort to encourage them to go. In any event, it’s clear that the Pandits no longer felt secure in the valley. It’s clear also that the state did not do much to reassure them of their safety.

Their houses, still full of their things, were looted and gutted and burned.

In some ways the Pandits are suited to life outside Kashmir. They held high social and economic status in the valley, serving, typically, as its doctors, lawyers, teachers, engineers. The community is widely literate. Much before the insurgency began, it was already ordinary for a Kashmiri Hindu to pursue his education in one of India’s bigger towns or overseas. Even without the uprising, surely some large part of the younger generation would have gone. But the Pandits who withdrew from the valley in 1990 withdrew to refugee tents. Their houses, still full of their things, were looted and gutted and burned. And when the violence did not subside, they felt they couldn’t so much as visit.

Certainly Anil thought he would never see this place again. He was educated in Jammu; he married there; he took a position as an assistant manager at Bajaj Allianz Insurance. “But destiny plays a big role,” he told me, smirking to distract from the sadness in his oil-dark eyes. In 2011, he came back to the valley. So did thousands of his fellow Pandits, most for the first or second time in over two decades.

The road blocks, the army caravans, the Indian soldiers in olive flak jackets are still ubiquitous. But Kashmir is entering a third year of diminished attacks; the insurgency has mostly been vanquished. In this time of rare calm for the valley, the Pandits are returning by the busload, mostly to visit, to escape Jammu’s summer temperatures, to marvel at the snow-white peaks and lucent saffron fields, to worship at the temples so essentially tied to their practice, to show those temples to their children. The exiles are anxious that this time away has weakened their Kashmiri identity and, by a fortunate confluence, the valley is readier than ever to receive them.

“The government has been encouraging them to come back at least, as far as I can remember, since 1996, when elected governments came into being,” said Omar Abdullah, the Muslim, half-English chief minister of the state of Jammu and Kashmir, sipping tea at his residence. “But every time a government made a move to bring back the Kashmiri Pandits, there was a backlash, and the Pandits who remained in the valley were actually attacked [by militants]. At this point it’s been ten years or thereabouts since the Pandit community was targeted. That in itself tells you how far we have come.”

Together, the central and local governments are offering incentives to Pandits open to a more permanent homecoming. Those who would restore their battered houses or build new ones can register for a rehabilitation package worth seven and a half lakh rupees ($13,800). And in 2008, Prime Minister Manmohan Singh announced that 6,000 coveted government jobs in the valley—half of them funded by the state, the other half by New Delhi—would be made available to Pandits under thirty-five, young men and women who were born here, but who came of age there, in the heat. 1,400 of those posts have so far been filled. Anil returned to teach Muslim students at a government school fifteen kilometers from where his father was gunned down.

Omar Abdullah made a brief appearance at last year’s Kheer Bhawani temple festival and was trailed by an assembly of devotees who threatened, in their following of him, to crush one another. It was packed. I wove, with difficulty, between the bodies. Yes, they said, we got along well with our Muslim brothers. Yes, we get along with them still now, we miss them. Yes, we are happy to be back. So happy to be back. Maybe, if the government will help us, we will come back here to live. The weather is very good, very fine. It is too hot in Jammu.

I sat with a group of young idling men in the shade. They had relocated to the valley in December of 2010 on the so-called Prime Minister’s package, which has afforded them government jobs and transit accommodation. That is where they met, in the village, Mattan, to which they were assigned. When I asked if they were glad to be back in the place of their earliest memories, they all three nodded. “My childhood friend, his name was Imtiaz, he was Muslim,” said Ranjan Jotshi, a Pandit with dark skin and heavy eyebrows. “I used to just sleep in my house and the whole day I would stay in his house. So when I first came back to the valley I straight away went to their place. Not to my own house; I went to their place. Imtiaz’s father was in the room and my friend told him, ‘Papa, do you recognize this person?’ And his father said, ‘That is my other son.’” Ranjan exhaled deeply. “First time I visited the valley after migration, when I just crossed the tunnel, tears were rolling down my eyes. That is the love for our Kashmir.”

Ranjan and another of the men wandered off and I was left alone with Amit Koul, a twenty-six-year-old social welfare worker. He had been laughing, but once his friends were gone his face became suddenly hard. “Let me tell you the truth,” he said, wrinkling the spot of red paint in the center of his forehead. “I was born here. So this place runs in my blood. But we are only here for the job. Hardly there will be any people who would like to live here. Everyone is settled outside. Whenever I get the chance, I will go to Jammu.” I asked him why. “Technology is lacking. You cannot roam here like we used to. Nightlife. There is no nightlife. You have to go to your job and then come home. That kind of thing is very difficult. But there is no other option. We have to live here until retirement. You cannot leave a government job.”

Young Pandits seem certain that this present peace is temporary.

By the conditions of the Prime Minister’s package, young Pandits can’t put in for transfers and take their government jobs elsewhere. As I would come to learn, most of them are actively unhappy about this and hopeful that the next government will reverse it. They feel that they are owed these jobs by reason of the trauma of migration, but resent that the posts are being offered as an avenue to resettlement. They seem certain that this present peace is temporary; they worry about being trapped in the region in a time of renewed violence. Almost all of the returnees on the plan have come back to the valley without their spouses and children, having left them in Indian cities with movie theaters and department stores and better caliber schools, cities more open on the world.

Ranjan’s Facebook profile still has him living in Jammu. His wife and daughter are there and he would be there, too, if not for the allure of government work. Most of the young Kashmiri Hindu returnees on the Prime Minister’s plan were formerly employed in the private sector. A lot of them were trained in jobs that don’t yet exist in the valley. The consensus among them is that the chance at a government post cannot be foregone. In India, such a job brings retirement benefits, generous holidays, fixed working hours, a near impossibility of being laid off. Pandits in their twenties and thirties remember their parents’ despondency and there are few things they wouldn’t do for an exceptional degree of job security.

What is a migrant community owed if indeed it left home of its own accord? What are its rights? And how to define “of its own accord”? Do a few dozen Pandit killings, amid tens of thousands of murders, justify a mass exodus? Does mounting fear justify a mass exodus? Does it matter that the Pandits have a history of escaping Kashmir for places of opportunity? Does it matter that most among the community had the resources to decide whether they wanted to flee or not? That while some migrants languished in refugee camps, others found better lives than the ones they had given up? These are the questions that arise when a government trying to rehabilitate its image internationally invites a migrant community to return using financial and other incentives. Many of the migrants have regained enough wealth to be able to respond to that invitation; so few of them were the victims of violence that they are actually willing to come. At the same time, about 3,000 Pandits stayed to live through the insurgency and have been all but ignored by the administration.

The Pandits who remained in the valley did so at the urging of their Muslim neighbors. “It never came to my mind to leave,” said R.K. Mattoo, a retired Pandit government officer, as we sat in the well-coiffed garden by the house his father built. “Everyone around here told us to stay on. They said, ‘We will take protect you.’” One afternoon, during the militancy, Mattoo told me, he was cornered by a band of young insurgents and he ran from them to the house of a neighbor. His Muslim driver convinced the men to leave. Meanwhile, the rest of the area was alerted and Mattoo was marched, in a procession of local Muslims, to the safety of his own home. His wife, Neerja, who had been trying to talk over him as he recalled the incident, nodded her head vigorously. “We didn’t have school-going children here,” she said. “If we had, perhaps we wouldn’t have been so brave.”

There are six Hindus left in the elderly couple’s locality. All of the others went without so much as a goodbye. “Trucks were sent everywhere to take us,” Neerja remembered. She was adamant that former governor Jagmohan had facilitated the departure and that he had acted in accordance with the agenda of India’s Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party. “He should have told the Pandits not to worry,” she said.

I had imagined that the Kashmiri Hindus who stayed behind would be happy to see the young returnees. But the relationship between them is immensely strained. By and large, the Pandits who remained in Kashmir are seen to have assimilated. The migrant community is certain that they could not possibly have maintained their faith and convictions under the conditions of the past two decades. “The migrants say we are taking beef, they are viewing us as traitors,” a man who did not go, Sanjay Tickoo, told me, “but it is we who kept the candle burning.” Having fled, the migrants received (and still receive) a monthly allowance; now they are entitled to resettlement benefits. They who endured the militancy and came out on the other side did not and are not. There is little fellow-feeling there.

The Kashmiri government, in calling for a Pandit return, often conjures the notion of Kashmiriyat, Kashmir’s self-asserted culture of diversity and tolerance. “I think the departure of the Kashmiri Pandits is a huge scar on Kashmir and our Kashmiriyat,” Chief Minister Omar Abdullah told me. “We would like that scar to gradually, if not be erased, then at least to fade away.” It is a nice idea. What is evident from the administration’s near-complete neglect of the non-migrant Pandits is that this great welcome is, at least in some part, a political tactic, a gesture of goodwill meant for the media. Prominent Kashmiri nationalists like Yasin Malik, chairman of the Jammu Kashmir Liberation Front, have been quick to adopt the same stratagem, visiting prominent Pandit places of worship for photo ops. Said Tickoo: “If Yasin will hug me that won’t make any big deal in the papers because I’m not a migrant.”

Last year, an article in the local daily Greater Kashmir proclaimed that no Pandit family had permanently resettled in the valley. Those who took greatest offense to the report were, naturally, Pandit families who had permanently resettled in the valley. Ashwani Raina, a Srinagar-born man with a round, kindly face and a flattened nose, left a geomantics job in Hyderabad to join in the Prime Minister’s package—so badly did he want to shake off the instability of the private sector. His wife, a Delhiite, moved with him to Kashmir; so did their two sons. She has an enduring chest cold and spends all day, every day, in front of the television. Until recently she was afraid to mark her forehead.

“My family is suffering here,” said Ashwani, now a draughtsman in Kashmir’s civil department. “You can compromise in each and every thing, but you cannot compromise in the basic things, the basic needs of your children. Cool climate is okay, you can enjoy climate, but you cannot eat climate.” Too much of his salary, he said, is spent on the renting of a modest house and too much of his time penning letters to officials, pleading for financial help. “I think they don’t want to distribute that package that they got from the center,” he said. “I have given the proof that I want to stay here. My family is here, my children are studying here. What now? Now the government should fulfill their promises so I can live the normal life.”

Most Pandits say that the government did not want or expect its invitation to be answered. They say that it’s happy for their tourist dollars, is glad to have them as visitors, but that is all.

They say, too, that the rehabilitation package on offer is nothing but a bit of propaganda. Just a quarter of the 6,000 government posts on offer have been filled, and that was in 2010. In June, a group of Pandit men arrived to Srinagar from Jammu and staged a hunger strike to demand that the next wave of successful applicants be announced. That request has not yet been met. There is not enough accommodation for the young people who have been brought over and what apartments exist are tiny and in disrepair. A new package, which would bring the amount of aid up to twenty lakh rupees, is under review. Meanwhile, close to no one has received the originally advertised seven and a half lakh rupees.

It is difficult to determine if the migrants left of their own accord. But definitely they have come back of their own accord. Most of the young returnees took a significant cut in pay upon their homecoming to the valley and they miss those extra dollars, big-city life. The Pandits who stayed find it more than a little hard to sympathize with them, except perhaps insomuch as the government is using them as political pawns. “The migrant youths have seen the larger world,” Tickoo said to me. “They have seen peace.” He grapples with the idea of thousands of Kashmiri Hindus who grew up elsewhere, and who would prefer to be there still, accepting a “resettlement package.” He wonders if this can be called “resettlement.” He wonders if they can even be said to belong to this place.

The road southeast from Srinagar is lined with cricket bats that swing like wind chimes from their display stands, and the lean Kashmiri willow trees from whence they came. An hour’s drive brought me to Mattan, where the government has established transit accommodation for incoming Pandits on the Prime Minister’s plan in the amount of three secluded brick buildings. Close to one hundred Kashmiri Hindus live there, in sixteen dormitory apartments (or “sets,” as they are called); a seventeenth is occupied by Indian security forces. The administration had advertised “individual accommodation,” but in Mattan, as elsewhere in the valley, every six or so people have been given to a few cramped rooms. Guests are asked to sign in on a firearm registration form.

One Pandit returnee, Kamal Butt, left the dorms after some time and began to rent a house from a Muslim lady so that his family could visit in the summer months. We sat in a circle on his living room floor, he and I and the young men from the Kheer Bhawani temple. “When I used to live with these guys, those were the charmed days,” he joked. “I quite enjoyed those days.” The conversation turned to which of the men were married, which unwed and which, by force of circumstance, just felt like bachelors. Many of them had met their wives in Jammu—Pandit women from Kashmiri villages far from their own. They considered the romantic potential of migration and broke into a collective giggle.

“It’s not just about giving people jobs and throwing them in the valley,” Kamal said, gripping his gurgling infant by the waist. “Government needs to construct more and more. Time is coming soon when they have to provide everybody with a separate set so that everybody can bring his family over. I think they must do it; they have to do it. They cannot leave us in the middle of the ocean.”

I asked to speak with Kamal’s landlady, a tall woman with a patterned headscarf. She is happy to rent to him, she said. She is happy that some Pandits are back. This is the most I managed to get from her on the subject. Finally, just once, she uttered a full sentence. “She thinks you look like a pigeon,” Kamal translated, pointing toward my neck, which had been bobbing as I laughed, and they began to laugh so hard that he struggled for breath. Many times I heard Pandits protest that the Muslims were only glad of their return because they saw it as a business opportunity. It was good to see them laughing together.

This is an important moment for Kashmir. Forgetting, for an instant, the politics surrounding their return: The young migrants are here. They will be here until they reach the age of retirement. They are very highly educated; they have known freedom and the type of modernity that has not yet reached this region stagnated by conflict. One wonders what the valley owes them, but one might also ask what they will wind up giving to it. They haven’t resettled after two long decades for nostalgia’s sake or for the weather. They are in their twenties and thirties and they’ve come back to work. If and when they feel comfortable speaking openly, they will find themselves in a position to make Srinagar more closely resemble the cities they so miss.

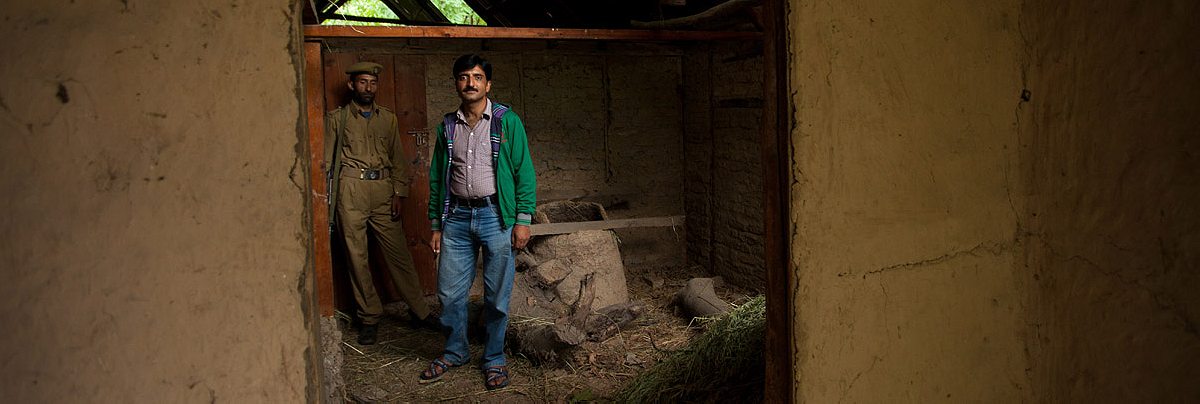

Sundeep Kichloo was born in Mattan and he, among the men who had been cross-legged on Kamal’s floor, was chosen to guide me. He pointed past the garlands of barbed wire, past a police volleyball game, to the forsaken Pandit homes. He remembered them as they were then. “This house belonged to a mister… I don’t remember what’s his actual name, but we used to call him ‘Bituji.’ And this, too, was a house. This belonged to a KAS officer from the community. At that time he was a little chap.” We came to a narrow stream and Sundeep let the rest of our group stray ahead. “This was a good place for we people,” he said softly. “It’s not so deep. But in our childhood, we used to bathe in this spring. It was near to our house.”

And then we were there, at Sundeep’s birth house. He looked at it, that corroding barn, as if at a photograph. “We missed our house for a long time. We will miss it for long, maybe until death.” And even as he stood there, just a few minutes’ walk from the dormitory where he sleeps, in the village that he is likely to inhabit for more than thirty years, he said, “But the thing is we will not come back to the valley again.” In his mind he had not yet returned. He was completing a job in some far-off place, nothing more.

I wondered: If the government were to make good on its promise of financial assistance, would he build a new house, bring over his wife and newborn girl? “Giving money is not enough,” Kamal interjected. “Suppose he takes money from the government and suppose he rebuilds his home. But he has to practically live there. It’s not so simple. The government needs to take steps to ensure his security. Kashmiri Pandits are in the minority and we always are scared of the majority. That’s a fact. Living here is not so easy. We are hundreds and those people are in lakhs.”

“Yes,” Amit said. “What is in their hearts nobody knows.”

I found him in a lawn chair on his porch, screaming words of affection and encouragement at the Muslim workers fashioning his new screen door

The Pandit migrants who sold their land did so by hasty verbal agreements and for many times less than it was worth. So many of the houses were—and still are—owned by joint families that could agree on nothing but to let them decay. I met a Kashmiri Hindu husband, wife and child who had made a permanent return in their boxy apartment and asked the father, Sanjay Koul, why they didn’t recover his birth house, which apparently was in habitable condition. “Because a number of shareholders are there,” he said. “It does not belong only to me, so I alone cannot do anything. It belongs also to my cousin brothers who have migrated from here and it is disputed among our relations.” Sanjay also owns a house in Jammu, which has been left behind, locked up. “We will decide what to do with it after retirement.”

Some of the abandoned Pandit houses have been populated by security forces, some by Muslims and many more have been set on fire. No one is certain of who burned them. Several Pandits told me that they had been set ablaze by militants bent on ensuring that the Hindu community would never return. Several Muslims told me that the Pandits burned the houses before fleeing, to further victimize themselves.

Only on rare occasions do Pandits come to restore the homes they vacated, as with Dr. Muju and his kin, who already have mended the ground floor and are renting it out to a Muslim family. When I visited, the concrete upstairs of their house was still in a shambles wrought first by the militants, then by the police and finally by nature. Its wooden steps were covered in bird shit and small white feathers. The officers who, for years, used the place for barracks took even the wood beams from the ceiling and the metal plumbing pipes from beneath the bathroom wall. The only thing that had not been stolen was a giant metal trunk, which apparently wasn’t worth the effort to haul down.

“A house is a house—even if it’s damaged, what does it matter? It’s our house,” Dr. Muju’s nephew, Praful, said. He pointed out the window to where the cherry tree and the black grape tree stood before they were pilfered. “Every person in the world identifies himself with some land. We identify ourselves with this land. This is what brings us back here.”

Dr. Muju, whose 80-year-old father refused to leave with him to Jammu and was killed in this house, sat out on the grass. He wondered why the administration officials were taking so long to inspect his reconstruction efforts and recompense him. “The government must help us if they are sincere about removing this stigma from their face: the migration of a minority community from a secular country in the twentieth century without any war, without any external threat,” he said. “We are very serious about coming back. Even today I can go to any Muslim family and they will show me the same love that they showed me twenty years ago. I can go there, knock on the door, ask for a cup of tea. The older generation still feels the loss of that.”

Only once did I encounter a Pandit who had received government money—an older man from the village of Mattan who spoke in exasperated shouts as though everyone around him were hard of hearing. Having returned to the valley, he began in 2011 to build a new house just steps from the wreckage of his erstwhile residence. Apparently, the government gifted him five lakhs, which he is using to complete an upper story. I found him in a lawn chair on his porch, screaming words of affection and encouragement at the Muslim workers fashioning his new screen door.

It is likely that this man, J.C. Kher, will return to Jammu in the bitter winters. Same for Dr. Muju and any other retirees rebuilding in the valley. Which is why some Kashmiris have accused the government of offering to help fund summer vacation retreats. Can someone’s battered ancestral house, or even the new building someone is erecting next to his battered ancestral house, be called a “vacation retreat”? How many months a year must you spend in a place to be considered to have permanently returned? Should the government be giving money to returnees who have decided to keep houses outside of the valley? I can only say that I watched Dr. Muju visit his neighbor, the huddled Muslim woman he had lived next to for years, and I saw her delight, and it looked very much like he had come home.

The Pandit returnees of the younger generation are united in many things, but mostly in confusion. They spent their formative years in refugee tents on the outskirts of Jammu, where Kashmir became just a name for their parents’ heartache. When finally they were grown and had regained some of the wealth and stability that their families had lost, they left it behind to come back to the valley and claim jobs that would ensure that they’d never lose everything again. They say that the private sector robbed them of social lives, but here, when they leave their government offices in the middle of the afternoon, they have no one to socialize with. They feel that Kashmir is stuck in time and that they’ve regressed; they feel the loss of their Muslim childhood friends, but still don’t know if it is safe to walk with them. They see themselves as being stationed here, not as living here, like soldiers on a tour of duty, only this tour won’t end for decades.

At least that is what they would tell me. But then sometimes, I would be driving with one or two or more of them, and the landscape would open in front of us, verdant mountains rising into snow or a lake overcome by the lilies of the season, and, reminded suddenly of the transcendent beauty of this imperfect place, they would fall quiet.

Kuldeep Raina and I ascended the hill to Wussan, a village on the other side of the Sindh River. Our car squealed in the mud. The house of Kuldeep’s birth, which is relatively intact, is being used now for police barracks. His family keeps three rooms locked and collects a meager rent from the officers occupying the downstairs, a band of young local Muslim men, who, Kuldeep remembered, used to call on him for help with their homework. When he returned to the valley for a government post, he came to this house, opened one of the bedrooms and decided he would live there, among them. The administration did not like that idea. He was asked, for reasons of security, to join the others on the Prime Minister’s package in the housing units reserved for them, which he did. He still visits Wussan once or twice a week.

Kuldeep’s in-laws by his sister’s marriage were among the Pandits who stayed behind. He nodded at their houses—at the little wooden boxes that hang off their façades, for enjoying the breeze, and at the old brick work. A cow lowed so loudly, Kuldeep had to raise his voice to be heard. “They who stayed have nothing to say; they have just to say yes for everything. When we are at Jammu, we can oppose anything which we do not like, anything we would like to agitate against. When we are here, if anybody says that we are Indians, we are Indians. If anybody says Pakistan Zindabad,”—long live Pakistan—“we, too, have to say Pakistan Zindabad. Only then we can survive here. That still exists.”

The Pandits who never left Kashmir have houses among the Muslims. But if thousands of incoming Pandits accept to properly reside here, they will surely establish their own colonies, or colonies will be established for them and those colonies will be heavily surveilled. Publically, the government has railed against the idea of Kashmiri Hindu settlements: “I don’t want to set up an enclave of Kashmiri Pandits, sort of an island of Pandits in the middle of nowhere,” Chief Minister Abdullah told me. There is a reason, though, why the administration has provided the returnees with separate transit accommodation abounding in security guards. If anything were to befall a young Pandit who had come back in response to government coaxing, it would be disastrous for Abdullah.

Some of the young Pandit migrants will have their families visit for months at a time. Some will have kids in this place and those kids will grow up Kashmiri, in the way of their grandparents. Even in the event of concentrated Pandit neighborhoods, things will be different. There are still Muslim children who have met so few Hindus that, when they see a woman in sari, wonder desperately where her feet are. That is going to change.

We came to Kuldeep’s own house and ambled inside. The police officers milled about in the dark and loam of what was formerly the dining hall. In every closet, every small opening, they were storing long, dry grasses for cattle feed. The kitchen was a mess of damaged clay. Kuldeep imagined what his mother would have said if, back then, he had tramped through the kitchen with his shoes on. Then he imagined what his wife would say if he were to present her with this dishwasher-less room, this defunct hearth. His eyes opened wide and he shook with laughter. “Really, I am happy to be back here,” he said and he seemed to mean it. “I love Kashmir very much.”

We climbed the stairs, warily. At the top, in a room full with cow grass, we looked out from the balcony at the wet fields and all of the gray untenanted houses. It was summer, but something gave Kuldeep to remember, with a start, “We used to take the snow from here and eat it!” He gestured towards a gap under the roof. “Papa would say, ‘No! Don’t do it! The cold will attack you!’” His children might never come to live in the valley, but one day he would show them the snow, he said.