A Dutch trio of coffee enthusiasts prove that the future of coffee looks an awful lot like its past

A bold statement surely, from someone who by the way pays his rent and buys his food with the money he makes pressing shots at an espresso bar. But as befitting the Dutchman who said it (Olivier Vos: buzzcut, with thick glasses, and a determined enthusiasm that would take apart a floor in order to fix loose grout), there is a tremendous amount of logic to what sounds initially like a blustery provocation. Coffee – even the finest, most confident, most edifying – is still just roasted beans and water. There are three young men in the Netherlands who want to take the barista, whom they see as a part-TEDx presenter, part-birthday magician, out of the equation. They want people to make their own coffee, and to make coffee they can be proud of.

Okay, so it might be a bit more complicated than that. The trio founded Koffie Leute calling themselves “personal assistants on the way to the perfect cup of coffee.” For them, the perfect cup is full of “slow coffee”, a liquid made with 21st century supply chains and 19th century patience. “It’s not just taste, but the experience of coffee,” says Olivier. Their coffee is ground fresh and by hand, put into a cup via V60 (a conical pour-over coffee filter used by most serious baristas these days), and ideally enjoyed over conversation (and maybe a cigarette, as Dirk, the most hirsute and least talkative of the bunch demonstrated often during our chat). “Espresso bars are espresso,” explains Olivier. “But Dutch history is just a good cup of coffee.”

You see, the protagonist of the story of the Netherlands isn’t William of Orange, Johan Cruijff, or Vincent van Gogh. The story of the Netherlands is all about coffee. Joint-stock companies formed in coffeehouses brought coffee to East Indies plantations to sell the beans back to the coffee houses, creating the need for enormous banks, even bigger ports, and something to go better with a cup than the native endive. Chocolate and tobacco, Moluccans and Arubans, shipwrights and navigators, were all brought in to an empire and later a nation founded on coffee. This is not to say that it’s a heroic protagonist, and one of the greatest Dutch novels, Multatuli’s Max Havelaar, describes and decries the plantation economy. But until the 20th century, Dutch coffee was Dutch coffee: fresh ground, more brown then black, and enjoyed with friends.

So what changed? Olivier says that factory owners forced their workers to take shorter coffee breaks, driving the men towards instant coffee. It is more likely that the bombing of Rotterdam, the World War II occupation (and starvation), and the subsequent loss of the Royal Dutch colonies did as much to coffee culture as modernization. Coffee was no longer a Dutch right but a commodity to share with the rest of Europe. Though Koffie Leute is attempting to reject the commodification of coffee, they are sharp enough to realize that much of coffee’s history is best left in the past. Bringing an Old World coffee culture back to the city while embracing ethically-grown coffee is tricky. A question about the beans’ origins led to a short if impassioned soliloquy by Martijn, the lanky Frisian with a Skrillex haircut. “The roaster knows the plantation. People tend to forget that…do you know if the guy who sold these beans to you went to the farm to get these beans?”

The beans we shared when I met them were Colombian by way of a Danish roaster, and at events Koffie Leute sells beans that are, if not from friends, from friends-of-friends. They have their origin stories memorized and are always ready to share this knowledge. It’s what they believe separates them from the standoffish irony that coffee people are infamous for. Knowing the beans’ story, the equipment’s story, and the country’s story – along with the enthusiasm to launch into well-timed expository – demands a dedication to the craft that purveyors of quicker coffee usually don’t have.

Slow coffee is different, perhaps because it comes from beans. Most coffee comes from tins or from coffee-extruding machines, known in the Netherlands as a Senseo. Martijn explains this and his distaste for the latter is palpable. Palpable distaste is a familiar reaction if you’ve ever had Senseo coffee. “It’s easy to sell something faster, not to sell something better.” The highfalutin espresso machine is even stranger to him, a Rube Goldberg contraption full of bells and whistles that purports to make the best coffee but is most notable for needing a jockey. The barista.

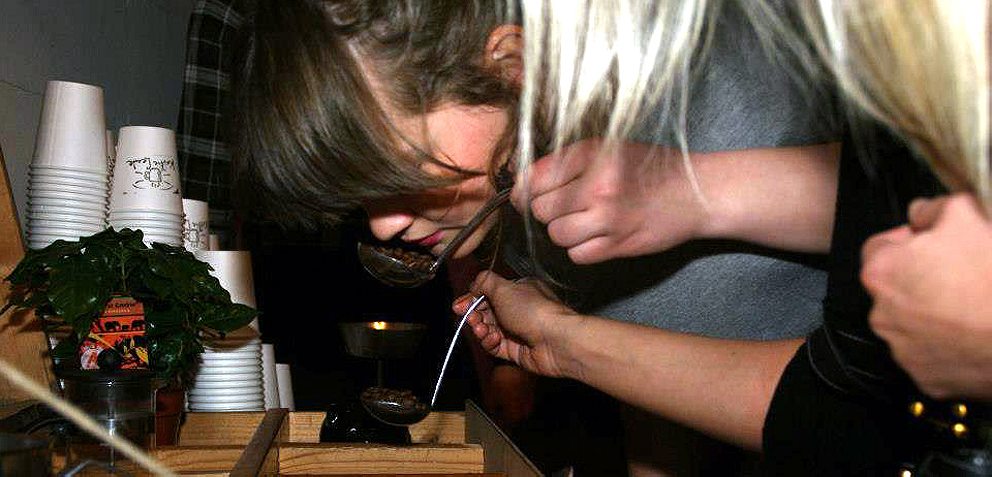

“All these people go to the expensive espresso bar with a hipster, rockstar barista. That’s not what we do. We want people to relearn what was lost.” Martijn and his friends thought the first step in this reeducation was breaking down walls. Particularly, the one between the front and back of the counter. Koffie Leute doesn’t hand customers coffee, it hands them the beans. The customer then pours the beans into a hand-powered burr grinder, closes its hatch, and gives the thing a good minute of spin. Next up is a trip to a specially rigged table the Leute made in the backyard, where filters are wetted and placed in V60s, with a fresh cup waiting on the gravity end. A few steady pours later and the coffee is ready to drink. This takes time, yes. But so does the thousand-euro rig on a matte-black counter. And here, the coffee masters are guiding and chatting every step of the way.

The grinders are all gorgeous pieces of mid-century carpentry. The little wood boxes were all bought at yard sales or spirited away from friendly attics. Refurbished by the trio, the chests hide the blades deep inside like pearls. A few spins on the brass handle leave one with a box full of fresh coffee grounds. Koffie Leute’s hand-ground beans are set to be a bit coarser, the better to be used with the slow-funneling V60. Most importantly, the hand grind with its dramatically lower revolutions-per-minute prevents frictional heating, which “pre-heats” the beans and gives them a slight – but noticeable – microwave effect. As one can expect from machines with generations of on-and-off use grinding coffee, they smell and look fantastic.

Olivier talks of grandparents seeing the grinders and coming up to him, telling stories of how they used grinders like these to make coffee for their grandparents in foggy old days. He tells the story of a guy who walked towards their booth and paid to grind coffee beans and pour cups, giving away the coffee he made. At festivals people mill around for the smell, and then share cups with complete strangers. The magic of the beans and the beauty of the grinders make for a heady brew on their own, but Koffie Leute isn’t averse to a bit of stagecraft either. Set up on a beach, they heat their water supply by bonfire and supplied a music festival with electricity-free coffee.

“It’s a coffee counter without a bar. Just a table,” Dirk explains. “We are searching for something more creative and interactive. The baristas don’t share their knowledge. I noticed that when I talked to customers at a bar, they really enjoyed it. We want to use this customer curiosity for good.” There is an idealistic bent to this, Dirk admits, and Olivier adds that they make a point not to wear a special uniform so that they’re on the same level as the customers.

But they are still Dutch, and they are still practical. Coffee has always been an at-home tradition in the Netherlands; the first espresso bar in Utrecht, the country’s third-largest city, opened six years ago. The number has grown, but people still tend to make their morning cup at home and their afternoon’s at the office. It’s for this reason that Koffie Leute has partnered with Roast.nl to mail the roasted beans to peoples’ homes. Of course the Senseos make things simple, but they’re expensive and they confuse coffee with a coffee-like product. The trio may be lacking the capitalistic drive and its many million reasons to suffer through acidic sludge – Martijn chuckled at the thought, saying “it’s not a venture capital thing” – but to paraphrase a young Ewan McGregor, who needs reasons when you’ve got coffee?

When it finally makes it to the cup, the trio’s slow coffee is going to be much less hot than a Senseo’s near-boil, and far more complex. Different notes play out as the coffee can sit on the drinker’s tongue without fear of burning it. It’s almost an unfair trick after you start with better beans, super-freshly ground, but it is another way to set slow coffee apart as good coffee. Martijn jokes that most Dutch like their coffee super hot because it seems fresh, even though it’s only just “fresh from the machine.” The filter and fresh grind let the grinder influence the cup the most, and it makes more sense for Koffie Leute to let the drinker do the grinding. Olivier explains that it is a week after roasting when a coffee is at its best, that the flavors are at their peak. But after two weeks, the coffee is flat, without all the extras. “And that,” Olivier sighs, like a man after a search and rescue mission gone awry, “is a shame.”

All three bring a tinkerer’s inquisitiveness to the coffee equation; any mention of a way to improve – or even just mess with – a basic cup is considered. Martijn has logged hours in a roastery learning how to determine the beans’ flavor by color and sound of the roast. He thinks customer-roasting is the next step after customer-grinding. Reading about how starving Dutch thinned their coffee with chicory (a la New Orleans’ Café du Monde) during World War II, they are trying it out to see which beans the root tastes best with. When I mentioned Stockholm pour-over institution Drop Coffee’s focus on the water, tittering of approval and possibilities swept around the table. All avenues are welcome, save one. “Milk is just used to hide imperfections,” spits Olivier. “We don’t mind sugar – it is your coffee – but milk is frowned upon.”

So how is the coffee? It’s…different, of course. Brown more than black and without any sort of lemony scorch. Koffie Leute has a handmade flavor chart for their customers that ranges from knoflook (garlic) to teer (tar). Their focus is on the Spring side of the spectrum; notes of cilantro, anise, jasmine, and basil. It seemed so impossible that my first thought was “these guys have no idea what they are doing with their coffee.” After another few sips, though, I noticed that I was not just holding the mug in my hands to warm me up on this still-chilly March morning but rather resting it against my cheekbone—the easier to smell, the quicker to sip, and the more to immerse myself in the coffee. I then realized that these guys knew precisely what they were doing with their coffee. It’s the sort of coffee that makes traveling worthwhile; so cocky and comfortable in its own norm that I, initially disgusted, grow quickly to admire it. The next step is bragging to all my less-cool friends back home.

This coffee is not a “reinvention” of coffee. It’s a reminder of what coffee is, was, and, arguably, should be. As seen in Stockholm, Berlin, and Brooklyn the future of coffee is here, it just needs to be distributed a bit more evenly. It does not need packets, pipes, or a pulsating machine. It definitely does not need a sleeve-tatted, standoffish sort to abracadabra a wad of Euros into a cup behind a curtain wall. In fact, hand-ground, poured, and shared over a low table, the future of coffee looks an awful lot like its past.