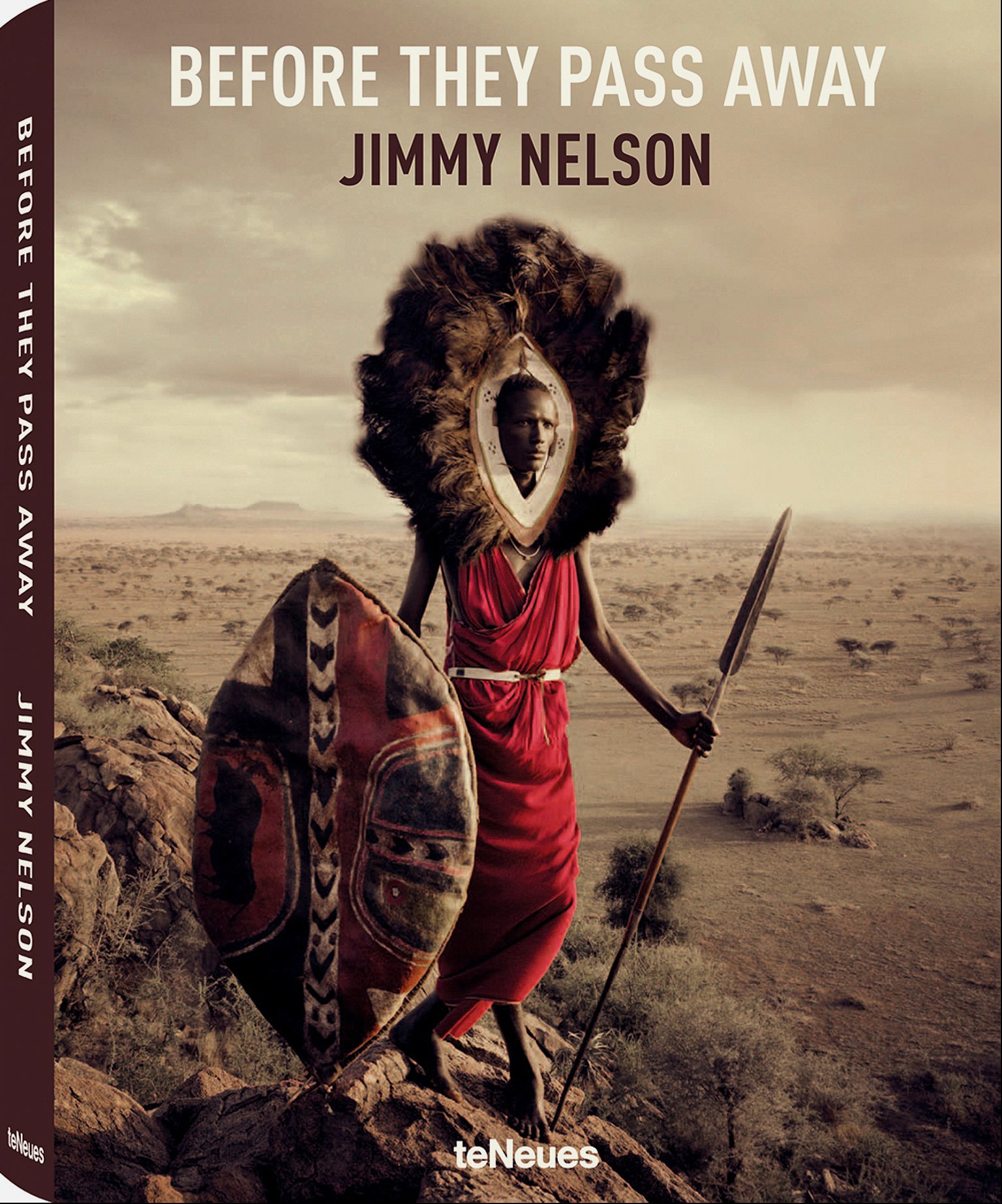

Photographer Jimmy Nelson immortalizes the world’s last remaining tribes before it’s too late, hoping to change their minds about modernization in the process.

Despite the obliterating march of modernity, Planet Earth is still a wild place. From the mountains of Mongolia to the desert of Namibia, deep in the forests of Papua New Guinea and jungles of Ecuador, people live in communities so remote that they are untouched by Western civilization. In his ambitious book “Before They Pass Away,” British-born photographer Jimmy Nelson travels to these places in the hope of immortalizing the world’s least-touched tribes before it’s too late—and maybe, in the process, showing what we have lost to modernization. He talked to R&K from his home in Amsterdam.

Roads & Kingdoms: Hi Jimmy, so how is it being back to normal life after such an adventure?

Jimmy Nelson: Well, I don’t see my life as ever being normal. Confronted by a number of things, one of them being all my hair falling out when I was 16, I disappeared to Tibet for a year to find myself at 18. [The trips abroad] have been going on for quite a long time. The only difference has been in the last year, I haven’t made any pictures because I’ve been consolidating and marketing this project. So that’s different, normally I would jump back and forth, do one and a half months away, then a month at home in Amsterdam, another month and a half away and so on. Those adventures are addictive because you’re in such a zone, you’re experiencing things and people in such a pure way. In the developed world, we don’t have that anymore. So the real adventure is how you can apply what you’ve seen and learned abroad and bring that back with you. But to be very careful not to be a hypocrite, I do live here. And this is where I have chosen to bring up my family.

R&K: You started the project with Ethiopia. Had you been there before?

JN: I had been to about three quarters of Africa already, but Ethiopia was new. I’ve subsequently been back there twice during the project. Southern Ethiopia is probably the most diverse place on the planet in terms of ethnic cultures in such a small space. It’s a little bit like Africa’s version of Papua New Guinea, there’s an awful lot happening. So I started there to give the project a sort of momentum.

I SHOT THEM FROM A VERY AESTHETIC, ICONIC AND ROMANTIC POINT OF VIEW

R&K: Before you set off for this first trip, did you have a clear idea of the places you wanted to go and the people you wanted to see?

JN: Yes, I have been researching the topic for years. I hadn’t anticipated being able to do it all in one go, but it had been a hobby since I began, since childhood. So I was aware of these locations, I had contacts in many of these places, some of them I had been to already in previous years. Next to that, I had a very specific idea of what I wanted to achieve and why I wanted to achieve it and how I wanted to show it.

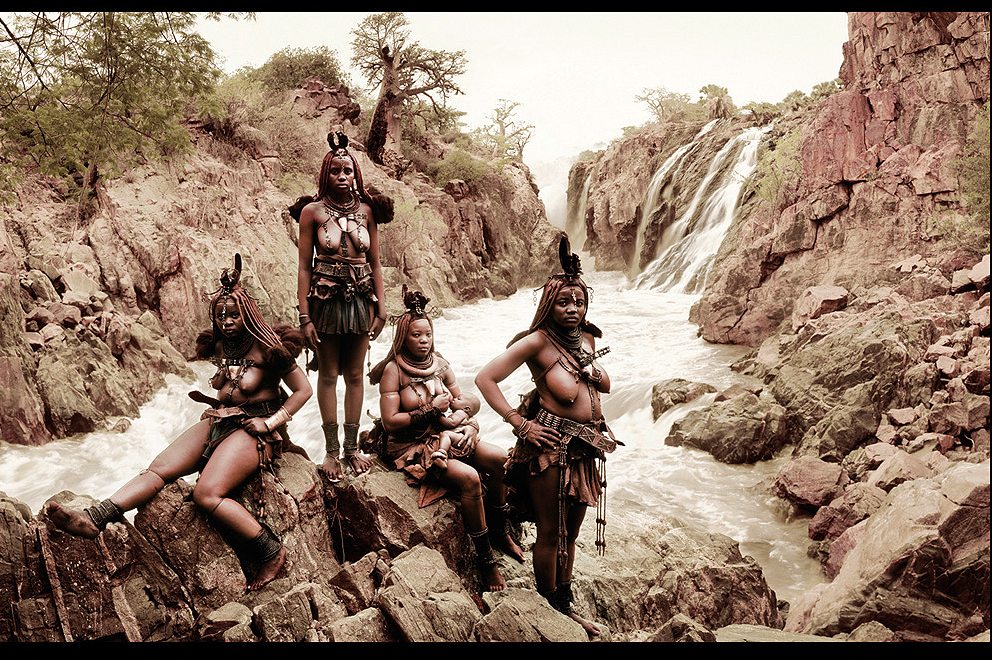

R&K: Can you talk about the very specific style in which you chose to present your subjects?

JN: I shot them from a very aesthetic, iconic and romantic point of view. When I was younger I had been to a lot of these places as a photojournalist. Then I worked for a number of years in the commercial world. I saw how you can attract people with a still image. I applied this gloss and veneer to the project. One of the main catalysts behind “Before They Pass Away” was after an exhibition, somebody rang me and said they’d like to buy a few pictures. I went to visit them and they lived in a sort of dynasty-style mansion. The lady of the house told me: “We’re very rich, we have more money that we’ll ever need, but we think going abroad is a bit dirty. We have four kids that we feel obliged to show that there is something out there. You make pictures of faraway places and faraway people in a way that we don’t find confronting, in a way that is also educational.” And then she gave me a blank check and she asked me to fill the stairwell. These are the people I’m trying to attract. The masses, the MTV generation has no idea – whether rich or poor – that these people still exists in the world. And the more that I promote the book, the more I share it, the more I’m flabbergasted by how intelligent, educated and in some cases very wealthy people have no idea that this still is on the planet. So that is the statement I’m trying to make with a still of photography that is aesthetic. It’s very romantic, it’s very subjective, it’s very idealistic, but it does act as a catalyst for a greater discussion.

R&K: Is that why you decided to have a lot of very posed pictures?

JN: Yes. The idea was stolen from an American photographer called Edward Sheriff Curtis, who photographed American Indians for 30 years. He made the definitive document of the last tribes of North America. The photographs were taken in a very iconic, romantic, posed way. He literally rode around and said to the very last people of these tribes: “Please pose for me, I want to put you in a position of stature.” He was mocked when he did that. He died bankrupt, divorced, and all his material went into somebody’s basement because they thought it was valueless. In the 1970s, that material was taken out, and it was hailed as the ultimate ethnographic document of that time, but it was too late, because that culture was gone.

R&K: Do you see an educational aspect to your work?

JN: Completely. I’m by default a photographer but without being evangelical, I’m also a messenger. I’m gathering information and I want to communicate it to others in the West and start a discussion here. But at the same time, I’m going to go back to all the tribes with the photographs, with the book and the film crew and will discuss with them who they are, why I was there, why I made the pictures, why we made the book, why we made money from the book, and why their ethnicity is so important. I believe they should not abandon their culture when they enter the modern world. They should take some of it with them because that is a wealth that we don’t have anymore.

R&K: So in a way, you’re also doing this as an activist?

JN: Yes, but it wasn’t intended. I did it from an emotional standpoint, showing that these places are special and these places are changing. But the longer I carry on with this project, the more that I think there’s something to be said that goes far beyond the photography. In the developed world we’re all becoming this homogenous mass of grey T-shirts, and many people are struggling with their individuality – what am I, what do I stand for, where am I from, what do I represent? These tribes, although we don’t necessarily have to be personally interested in them, they represent for us an individuality, a balance that we’ve lost.

I WANT TO TELL THEM NOT TO ABANDON ALL OF WHAT THEY ALREADY HAVE, BECAUSE IRONICALLY THAT’S WHAT WE’RE TRYING TO RETRIEVE

R&K: Do your photographs depict daily life or particular moments like celebrations, ceremonies?

JN: Eighty percent of what you see the people wearing is what they wear on a daily basis. The rest is their ceremonial dress. So, yes on some occasions I was there at a festival, at a wedding, but on all occasions I said to the people: “I’m here to celebrate you, I’m here to put you on a pedestal, I’m here to make you feel special, please present yourself at your very best and at your very proudest.” The majority of them were unaware of what a photograph was or what I was going to do with it but they were all aware of being vain, they were all aware of me saying you are special.

R&K: After you gave them these instructions, did any of them do something that you either weren’t expecting or went in the opposite direction of what you were looking for?

JN: No, they all did exactly the same as what we would do here. They all posed. I spent a lot of time on my knees, taking photos from a perspective where I’m very low and they’re very high. It’s about status, making them more important than I am. There was only one occasion where it didn’t work. I went to the aborigines in Australia twice and because of the cultural problems there, I was unable to photograph them. They are suspicious and to them, I was a nobody. But my hope is that I’m going to go back and explain that if they give me a little bit of attention, they can see what I’m doing. I’m not just there on holiday and my feeling is that they’ll have a different way of looking at me and my work.

R&K: What do these people have in common?

JN: They share extreme individuality in their appearance, extreme creativity. They also share a way of living together because these people are so remote and they’re so in balance with themselves and with nature, as well as the community within which they live. But they don’t look like one another, that’s the beauty. From a sociological point of view, they will all modernize, that’s inevitable, just as we have. But it’s going to happen in a far more quicker way because of the digital era. They will all soon have internet and mobile telephones, and they will all become homogenized through the information that they receive. What I’m going to try is persuade them that they’re already rich, that they already have something that’s very valuable in the way that they live and how they look. As they follow others into the developed world and get their car and their telephone and their TV, which they have all the right in doing, I want to tell them not to abandon all of what they already have, because ironically that’s what we’re trying to retrieve.

R&K: Do you think there is something governments can do to stop these tribes from disappearing?

JN: Well, somebody asked me the other day: “by visiting them, by promoting and talking about them, aren’t you creating a glass house effect?” I said maybe I was in my own little way, but isn’t that the lesser of two evils? One evil is they disappear—they don’t die but they move to the city. Option B is that a percentage remains behind, and they dress up for tourists. Is that a bad thing? They’ll probably be happier and healthier staying in their natural environment, earning an income from tourism. And even though it becomes a little bit fake, is that the lesser of two evils? I know which evil I prefer. If governments see there’s an income to be achieved from that, from leaving them in their natural environment rather than having them as a burden in the cities without a job, is that a bad thing? Maybe not, especially if in the process, they learn the value of their culture.

“Before They Pass Away” is published by teNeues