An unsolicited email turns into a strange junket by land and sea in Mozambique

The email invitation looks suspiciously like a Nigerian scam. “It is indeed with much pleasure that I write on behalf of The Hon Mr. Fernando Sumbana, Minister of Tourism in Mozambique… The grand prize (a global first) is winning an Island Paradise!”

The invitation: a three-day press junket on chartered planes to a couple of luxury hotels and a tropical island. Subsequent conversation with excited PR reps hired by Mozambique is peppered with exclamation marks and numerous mentions of “7 star!” luxury.

There’s an air of the surreal about the Whole Exercise.

But we journalists, knowing better than to ask too many questions when there’s a holiday-that-can-be-passed-off-as-work trip—especially during a Johannesburg highveld winter—swallow our doubts, dutifully slip on our press tags, get on the plane. Itinerary: the capitol Maputo, the coastal city of Vilankulo, and an island in the Bazaruto archipelago offshore.

***

There are only two letters— M A —crowning the apricot and tinted blue glass monstrosity that passes for Maputo International Airport.

The airport is a touch of modern-day Beijing amidst the balmy sea air and construction sites of the capital, replete with pinyin characters signalling whether the loos are occupied. The old terminal, with its aged tobacconist, sun-drenched deck and dim wood-paneled charm, is being demolished behind a ceremonial Chinese gold leafed archway for good luck.

We’re met by a platoon of strawberry blonde South African PR folk who are relentlessly enthusiastic, even as they wait for immigration officials to figure out the new ID cameras – some of the spoils of a three-fold increase in tourist visa fees.

“Obrigada,” I say, as one of our chaperones hands me my passport.

“What? I don’t speak that. English, please,” he frowns.

Our gear—television cameras, radio kit—is confiscated by customs, who apparently haven’t yet received the memo from the Ministry of Tourism about their country’s “Win an Island Paradise!” campaign.

We retreat to a Chinese travel coach.

***

The Avenida Acordos de Lusaka is bustling as our bus rumbles past, the asphalt seemingly unscarred from the burning tyres, blood and bullets of the 2010 riots, when Maputo’s rapidly urbanising impoverished classes realised they could no longer afford bread, water, electricity. An enterprising paint fairy has red-washed every third wall with the Vodacom logo.

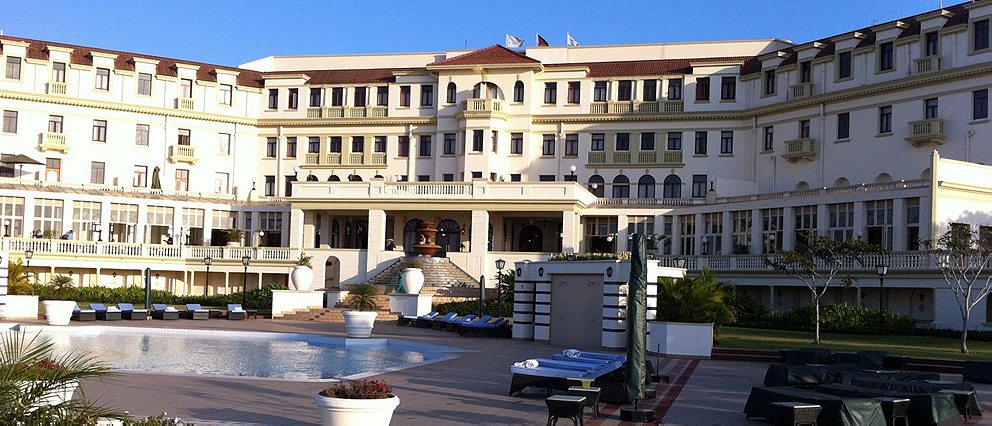

Just beyond the revolutionary corner of Avenidas Mao Tse Tung and Julius Nyerere, the Polana Hotel rests on a slope, gazing patiently out to sea. In the last two years, Maputo’s grand dame has had her tired whitewashed walls spruced to a pale butterscotch, embracing the dull-happy-medium of international 5 star mediocrity.

Her gentle yet imposing lines were drawn by Herbert Baker, architect of record on some of Africa’s most important and self-important colonial buildings. She holds the secrets of Mandela, Carter and Kabila, who have overnighted here, as well as of brigades of Allied officers on leave. But in recent years, her body has been given over to the present-day Aga Khan, the 49th Imam of Nizari Ismailis, who happens to also be a hotelier. His “detailed and sensitive renovation” has delivered her to the sanitised monotony of the Serena Hotel chain to which she now belongs.

Several terracotta carp leap out of an enormous fountain. The monochromatic checkerboard lobby tiles have been replaced with ceramic pavers reminiscent of a casino interpretation of Tuscany. The lift grilles are gone, making room for countless mirrored panels.

Lunch al fresco: I stare at the smoked salmon sushi on my plate, no doubt a demonstration of the cosmopolitan-ness of Mozambique’s capital, and a sad misunderstanding about what makes the country special.

We escape onto Maputo’s cracked pavements, power-walking in search of real local-colonial delicacies before the back-to-back press events, scheduled with un-Mozambican precision. The sunlight outside the air-conditioned hotel is rich, warm, friendly, caressing, and as creamy as pasteis de nata, the flaky savoury pastry with custard centre that we’re looking for.

Back in the hotel: it appears that a very earnest Mr. Sumbana, the Minister of Tourism, is indeed intent on re-branding Mozambique as a “luxury!” destination. “I don’t want Mozambique to be known just for its sun and sand,” he says to a sweaty press room. “That’s why we’ve decided to help people win a villa on a tropical island.”

There’s going to be a reality television show, with fifteen lucky SMS competition finalists exploring the beauty of the country in all its forms. One winner will win a villa in the Bazaruto archipelago for 25 years, rent and all.

“What if one of the finalists isn’t all that… television friendly?” I ask the visiting guy from the Travel Channel. He laughs nervously.

***

The Prime Minister comes to dinner, in the Polana’s newly refurbished ballroom. We eat tiny, sweet, local oysters and posh chicken zambezi under 22 chandeliers, and stare at the evening-wear of Maputo’s mayor, an ensemble seemingly made of fuchsia upholstery. In front of the backlit palm trees, widescreen television screens depict scantily-clad blonde women frolicking on beaches and sipping cocktails, while swordfish made out of beads hang surprised over fat lily centrepieces.

Few seem to notice the acoustic guitar player, eyes closed, running his fingers over his strings, creating his own passionate personal blend of Mozambican marrabenta, fused with a dozen other provincial musical influences.

They should notice him. His name is Jose Mucavele, and the last time I heard him play, it was dark, we were at a small music festival, on the sidelines of a trainline going nowhere fast, drinking a locally brewed love potion out of a gourd. This time, it’s a little less atmospheric.

There isn’t enough time in Maputo.

Not enough time to drink tepid gin and tonics during the witching hour at the little roadside shipping containers-turned-barracas in Museo. Nor time to watch the fishermen slop in with their catch at dusk at the barra de pescadores on the little dirt road north of town. Nor time to wander through dusty streets perusing the dilapidation of some of the world’s finest Pancho Guedes Art Deco masterpieces.

Instead, we retreat to a deserted Club Naval, next to a dimly-lit lap pool on the Indian Ocean, and sit, drinking dark, sweet and malty Laurentina Preta beer on a night with no moon.

It’s an unusual Maputo. The town feels moody, full of Wednesday evening ghosts—a gregarious gogo dancer turned in early.

Sitting next to a rickety stage, the reggae night band is on a break. They make their evening comeback with an acoustic version of “Blue Suede Shoes”. I have a brief flashback to my father’s amateur karaoke competition glory. A friendly Mozambican in bermudas and bling belt buckle insists he wants to help me feel at home. He raises his eyebrows suggestively.

The night is chilly. The air has lost some of its salt on its way up from the harbour.

***

A trip to the coast: Fluorescent-vested Ignacio has blindingly-white teeth and a Colgate smile. I insist on sitting on top of the luggage, stacked on an open-backed bakkie, en route from Vilanculos airport, so we can chat.

He loves his town, its dusty streets lined with stalls selling sad bananas. The open-air school with its mesh gate and noisy chants at recess. The tidily raked lines in the sand of tended hut compounds, set back from the road.

He doesn’t love the Chinese man in the big grey truck, spraying water on the dirt, preparing it for tarmac. “They’re not good people,” he explains to me, unselfconsciously, not overly concerned about my own Asian heritage. “They’re here and only good for money.” I assume he means they’re looking for it, rather than handing it out—but it’s unclear, given Beijing’s penchant for concessional loans with murky fine print. “We’re not friends with them,” he adds.

I find it hard to believe that there’s anyone Ignacio isn’t friends with.

***

On the boat to Benguerra Island: Staring into the pristine depths, I’m wracking my brain to come up with a description of the water that doesn’t involve a cliched semi-precious stone. I settle on “luminescent”. Everyone else on the deck is too gleeful with quasi-holiday cheer to roll their eyes.

It’s the exact colour that seven-year-old Samantha Taggart showed me on her art smock in primary school, when we were playing come-up-with-an-obscure-colour-and-run-across-the-sandpit-tag. “This is aquamarine, dummy.”

No one else seems to notice the barnacles on our boat captain’s face as he stares forward, unperturbed by the patches of rain moving across the strait, soaking the occasional dhow. The humidity strokes our eyelids as we close them to the wind.

***

The shirtless drunk in torn indigo shorts is waving at me.

Stumbling, grinning, leering with a patronising smugness, he’s strolling down the beach, past luxury villa number 4. He’s headed in the direction of the local village, following the damp footprints of local fishermen in the ridges of the receded tide. His torso is sun-darkened, his sneer wide and dizzy.

“It doesn’t happen here very often,” says Billy, the activities coordinator, with an embarrassed sideways glance, as we stare out at the mainland over a sundowner glass of Amarula. “Mostly, the villagers are very friendly.”

***

At Marlin Lodge: There’s wilted bougainvillea in the loo of luxury villa number 4, and cowrie shells on the bed. The shells spell “W-E-L-C-O-M-E”, but with no exclamation mark. There’s wilted bougainvillea too in the earthenware pot, for feet-washing from the beach, on the deck. And artistically strewn foliage over the kettle and sachets of instant coffee.

I stand in the outdoor shower, steam rising to the stars, and imagine who holidays here when it’s not filled with correspondents on a junket. It’s the kind of lodge where the tourists don’t carry disposable cameras, expect bubbly with breakfast and wear big watches. It’s stunning in its beauty. It’s bland in its perfection.

We sit obediently in fishing dhows as their masters raise weathered sails. We drink cold 2M lager from the can out of pre-packed cooler boxes. We sail in a small crescent around the bay and watch the lodge staff hang coloured paper lanterns from the water. The sunset causes a press Instagram orgasm.

Supper is served at a long candlelit table in the sand after the requisite local drumming. Everything’s locally sourced—the crayfish, the coriander, the cow. Chef Armindo’s earthy homemade basil pesto is a welcome refrain at every meal. The food is a triumph: the butternut pumpkin soup just gingery enough to be interesting, the king mackerel fresh and dense and slightly metallic. The wood-grilled prawns firm but creamy, and the local chili from Armindo’s veggie patch appropriately explosive.

There are chest-high wood skewers for the marshmallows, to be lit in the bonfire from the security of picnic blankets beckoning from the beach. A sliver of a moon gazes down at the escapism before her, an evening of 80s Club Med classics blaring from a tropical beach bar and journalists asleep in the sand.

***

35-year-old Jose makes an excellent caipirinha and has an excellent deep, throaty laugh. He has bartended at Marlin Lodge for nigh on 14 years, also lugging wheelbarrows full of concrete periodically when the place needs post-cyclone attention. He lives in the local village on the other side of the marsh, which isn’t quite exciting enough to keep him entertained, he says, with a shy smile.

Jose earns about $250 a month, double the wage of most of his colleagues, mainly because he can make a damned good caiparinha. He’s quietly proud that he can now speak English, but mostly that he makes more than most of his friends on the mainland, where his wife Helen looks after their two girls.

It was quiet all last year, he says, here at the lodge. But now it’s picking up again. And as long as tourists keep coming, he nods, the lodge can keep building schools and ferrying people to the mainland for medical treatment. He’s proud that his caipirinhas can help with that.

Nastasya Tay is a freelance journalist based in sub-Saharan Africa. Amongst her wanderings, she’s covered riots, migrants and artists in Mozambique for The Guardian, the AP and the BBC, and is pleased that this qualifies her to pronounce on tropical islands. You can follow her at @NastasyaTay.