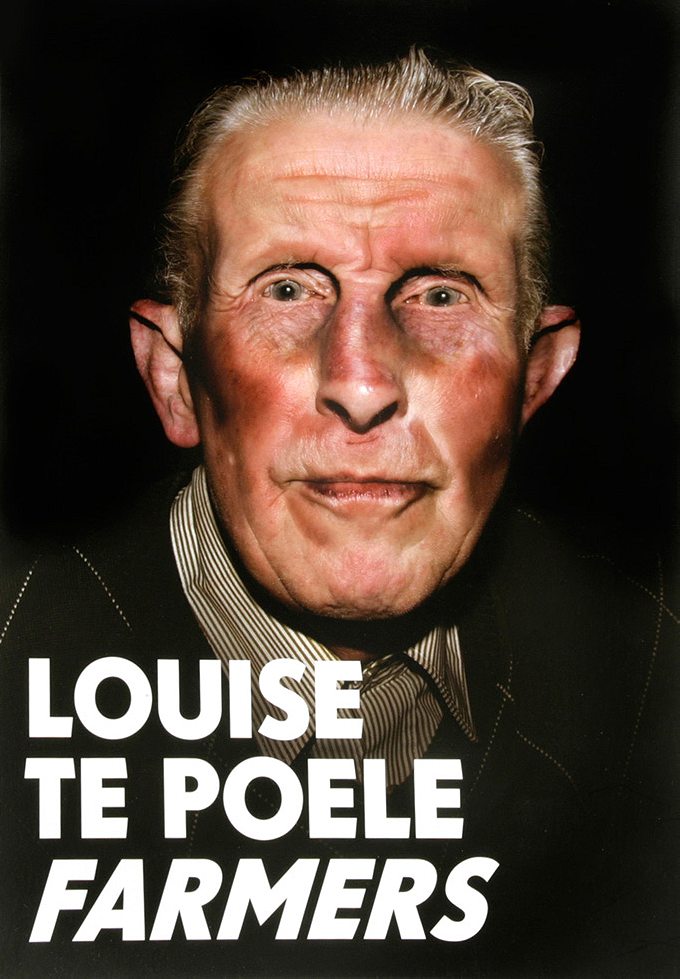

Photographer Louise te Poele returns home to photograph the farmers she knew as a child. An R&K interview about her controversial work.

From August Sander’s earthbound farmers of the Westerwald through Grant Wood’s American Gothic, there’s a long history of presenting old farmers as some immovable part of their own landscape, weathered trees rooted to their land.

Not for Dutch artist Louise te Poele. The farmers in her pictures stumble from the darkness, maybe drunk, maybe dancing, always mid-gesture, literally painted with life (the warmth of their skin, the blackness of the background all juiced up in post-processing).

Her photobook Farmers, just released in the United States (but best ordered from her website), has attracted some criticism for its “grotesque” rendering of its subjects. But any critique of te Poele should include an acknowledgement that she is, at the very least, intimately connected with these people. They are, in fact, her family and neighbors.

The 28-year-old lives in the city of Arnhem now, but she grew up on a farm (“pigs, sheeps and horses”) in Lievelde, near the German border. I caught up with her by IM to ask about her book, her critics, and just how much drinking went on before she brought the camera out. Here’s an abridged version of our chat:

Roads & Kingdoms: How did your background bring you to this project?

Louise te Poele: The Farmer series began when my father asked me to photograph his neighbour’s 50th birthday party. At the time I was in London [and] the photography I was doing was mostly fashion related. So when he asked me, I was like, no way, I’m not a wedding photographer.

But paternal pressure… he was saying to me, the neighbour was always so nice and kind to us, how many times did you borrow her bike to get to school. I agreed and when I came there, I saw something in them.

R&K: So they are all from Lievelde?

LtP: The first photos from the series are my neighbours and their guests, who came from the Achterhoek region, and my father. And to complete my series I went out looking for people who could fit in, but nothing is posed.

The last two photos were made from two farmers in Amsterdam. I had gone to horse markets in the early morning together with my father and friends, but the people from the market were too damaged, they smoked too much and they ate too much fat. I was looking for the farmers I remembered from my childhood.

R&K: So you had an idealized farmer in mind?

LtP: I guess so… I wanted to show the beauty of these people, and I think it’s more personal. No one is going to take over the farm of my father, so for me this is maybe the last generation of farmers.

R&K: What is happening with your father’s farm?

LtP: My father is still running it so it’s still there, but I don’t think my brother or sister will take it over.

R&K: And you?

LtP: Ha ha no, maybe to build my photo studio in one of the sheds.

It could also be that when I went to art school, and my whole farmers’ background was gone. so when I came back there on that 50th party, I realized that they still were there. A part of what I want to say in this series is that these people are what they do: you see the land in their hands and in their faces.

R&K: What’s your answer to critics who say this is demeaning to the farmers?

LtP: I photographed these people as how I see them, and they are the most beautiful people I know.

R&K: Is there an ethical problem with drawing on the pictures and otherwise manipulating them?

LtP: No. My photos are my personal work, they are not pretending to tell the truth. I see my photos as paintings. The photo is the starting point, and I’m painting on it to enlarge the things which are triggering me.

R&K: Last question, asked without judgement: How drunk were these farmers?

LtP: I shot most of them at parties, [but] they could all walk straight.

Buy te Poele’s book from her website, or see her Farmers series through October 20 at the Gallery Bart Nijmegen, or at Mooi at the K11 Art Mall in Hong Kong.