The “micro-nation” of Christiania has stood in the center of Copenhagen for 40 years. On July 1st, it’s being sold.

People get filled with shit about us

Thousands are taught to hate our guts

Without knowing who we are

—from Christiania’s “national anthem”

The Danes have a natural sense of industry about them, even the ones that are by disposition burnouts, squatters, or hippies. And so, from its first days as a commune on an abandoned Naval base in the heart of Copenhagen, Christiania was less an abstract idea than an ongoing construction project. For forty years now, scores of busy little Danes have been behind the walls of Christiania, hammering, tilling, leveling, toking, cultivating, fucking, graffiti-painting, cat-napping, woods-shitting, house-building. “Originally we were some people who grew tired of talking,” one of its many founders said in an early documentary about the place. “You know, people talked a lot in the late ‘60s. Instead of talking about how life could be, we said, let’s do it. Here were the possibilities. A big, beautiful area in the middle of town.”

It’s that size and the improbable longevity of what they’ve built that sets Christiania apart from any other squat or collective I’ve seen. And I’ve seen my share. In my 20’s, I used to slum around in Tacheles, the last of the artist-occupied East German apartment blocks on Berlin’s Oranienburger Street. Before that I spent a brief sojourn in a boarded-up squat in Brixton, London, eating at a nearby Anarchist cafeteria, where the ingredients were either shoplifted by the Black Bloc or liberated from trashcans. I spent years living in west coast college co-ops in the states, though I never quite committed, as some of my cohort did, to becoming “farmer freaks” who took their college degrees to rural communes to grow vegetables and dance naked on the solstice. The idea of squats, occupied lands and alternative communities, though, still appeals to me, as it should to anyone with a pulse. They are essentially treeforts for grownups, where you can duck out of society, write your own rules, bond them with blood oaths, smoke cigarettes, kiss the girls, whatever you want. That’s the promise: you make your own reality.

But all the other treeforts I’ve seen have been so small, so crowded out by the cities around them. In Brixton, there wasn’t enough room for the anarchists and punks to live together, so we fought. Or rather, the punks kicked our asses, and the anarchists had to retreat to even smaller spaces. Try sleeping in an empty clawfoot bathtub. The romance of the freedom wears thin quickly.

(More from Roads & Kingdoms: 16 Things to Know Before You Go to Denmark)

What amazement, then, on my first day in Denmark, to set my bags down in a rented apartment on Bådsmandsstrædes, and walk through the Christiania gate to find almost a thousand men, women and children living on more than 80 acres, from the urban grit of Pusher Street to the shire charms of the hobbit-homes lining the lake. Yes, Pusher Street, the glowering heart of the commune, is as menacing as advertised: run by biker gangs, selling drugs to partiers, not idealists. It has long been the enemy within the walls. But what surprised me was everything else that Christiania has built: bars, grocery stores, cafés, a vegetarian restaurant, concert hall, art museum, an elementary school and day care center, even stables with a dressage ring. It is not a squat or a sit-in, but an entire occupied city.

My guide to this first day in Valhalla was Tanja Fox, 44, daughter of a Danish hippie and an American photographer who escaped the Vietnam draft. She was only four when her mother and sister were among the first settlers here. She raised her own children, now teenagers, here, and her life in a tucked-away Christiania enclave called Dandelion seems a model of utopian contentment. She drinks herbal tea, wears knit sweaters, grows fat-lipped Technicolor tulips in her garden, and takes her terrier named Yupi on 6am walks through Christiania every morning. She took me on the same walk that first day, up past the geometric Banana House, along the old rampart that was built centuries ago to keep the Swedes out, and down to the newly seeded lawn that slopes into the lake. More handmade Christiania homes were huddled cozily on the far shore as a breeze picked up the sails of a toy boat in the lake. “Look at this,” she said. “We are living in heaven.”

This heaven, though, has an expiration date: July 1, 2012. That’s the day when, after decades of pitched battle with Danish authorities, Christiania finally bows its head to accept the most basic, and hated, rule of outside society: land ownership. All 84 acres—minus some environmentally protected land—of previously occupied government land will transfer to a foundation run by Christiania for a price of 76 million kroner (nearly $13m USD). The process has been giving the bland bureaucratic name of normalisering (normalization), a word that seems market-tested to stick in the throats of the proudly abnormal Christianites. A team of four staffers at Denmark’s Palaces and Properties Agency, headed by Marija Theiden, will oversee the land purchase. Though Theiden wouldn’t comment on the political implications of normalization, she told me that “all parties voted for the agreement” and that the process of selling the land to its residents was “one of the most broad agreements in Danish politics.”

(More from Roads & Kingdoms: Gin and Tonic, A Love Story)

In the end, Christiania was forced to submit to Danish politics by a combination of sticks (police action, selective bulldozing) and carrots (offers of guaranteed loans and steeply discounted pricing). For a social experiment that was predicated on the idea that private property of any kind was corrupting and immoral, this is a bitter pill. As Fox puts it, “we never wanted to own anything.”

She and others are putting a brave face to the changes by selling “shares” of Christiania (Folkeaktien, as they’re called in Danish)—more of a Kickstarter project than an actual stock issuance—to give a communal bent to the purchase. The collective will be the owners, individual homeowners will not. Fox staffs the Folkeaktie office by day, and she has helped organize a ten-day Folkeaktie festival ending July 1st. It will feature, as one brochure put it, the “best and worst that Christiania has to offer”, with big name DJs; an art auction; open houses; and sales of Christiania shares, beer, and (though the Folkeaktie people won’t be involved) the products of Pusher Street. When everyone wakes up the next morning, the land-owners of Christiania will have big questions to answer. Is this really the end of the longest-running collective in modern history? Is it a new beginning? Should we all just get high and try not to freak out?

Drugs, Not Hugs

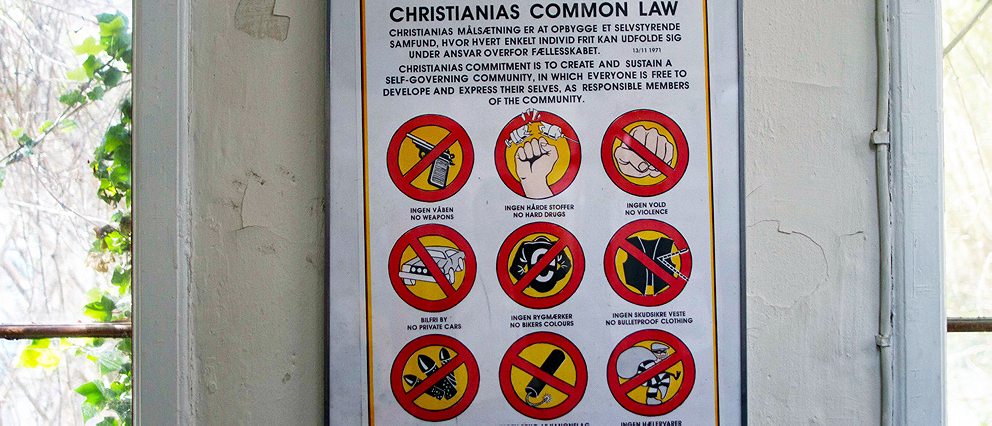

Jakob Ludvigsen, a journalist and activist whose altweekly first encouraged Copenhageners to “immigrate” by bus to the abandoned Bådsmandsstrædes Naval Base, helped write Christiania’s mission statement back in 1971. It read, in part: “Our society is to be economically self-sustaining and, as such, our aspiration is to be steadfast in our conviction that psychological and physical destitution can be averted.”

Ludvigsen, who now covers the local intrigues of the far-flung island of Bornholm in the Baltic Sea, wouldn’t talk to me for this story—“what do you want me to say? I represent the past,” he wrote me before going silent—but if there is one strip of “psychological destitution” in the Kingdom of Denmark, it would seem to be Pusher Street in Christiania.

(More from Roads & Kingdoms: Adjika, Sauce of Glory, Pride of Abkhazia)

Pusher Street is an open-air market controlled, with coercion, by the Hell’s Angels and Bandidos biker gangs. In recent years, they have recovered from a massive police dragnet in 2004. They’ve also fended off immigrant drug gangs in a struggle that occasionally erupted in bloodshed (a grenade attack at the picnic tables of adjacent Nemoland food/beer court, automatic weapons fire on Pusher Street itself). Their prize? An enterprise that police estimate does a billion kroner ($166m) worth of business a year. Pusher Street is not just an eyesore for Christiania, say authorities, but a transit hub for much of the estimated 20 tons of weed that Danes smoke a year (possibly related: Denmark’s recent ranking as “happiest country on earth”). Denmark’s neighbors complain that Pusher Street is a waypoint for much of the drug traffic into Scandinavia.

“People from the organized crime world are taking advantage of Christiania,” says Karsten Lauritzen, a member of parliament from the center-right Venstre party, which had been in power for much of the last decade and had, it should be noted, long tried (and failed) to eliminate Christiania altogether.

(More from Roads & Kingdoms: A Body on Barranquito Beach)

Drugs have always been a part of the colony. Where there are hippies, there will be weed. “The founders needed it to, you know, free their mind a little bit,” says Fox. But as the 70’s hardened, the Free Town of Christiania, in a pattern that would be repeated over and over, caught the devil. Back then it was heroin. There’s a dispute over how the junkies first came: was Christiania used as a “trash can”, as one resident put it, for dumping addicts from Copenhagen neighborhoods like Vesterbro and Nørrebro? Or did they spring organically from the enclave itself? Either way, junkies took over the “Ark of Peace”, a large military building, and soon enough were stripping the plumbing for scrap metal, dismantling the building, all but smoking the floorboards.

And then, in a rare moment of muscle, the street theater activists and modest homebuilders and utopian anarchists of Christiania flexed in unison. The result was perhaps Christiania’s signature achievement: the Junk Blockade of 1979. The community mustered enough consensus to outlaw hard drugs and institute mandatory urine tests for suspected addicts, combined with threats of expulsion and offers of homegrown rehab options. Summer of love met tough love. That victory was followed by the ouster of a biker gang that went by the name of Bullshit—that had, in its day, controlled the marijuana trade and bullied the weak in Christiania.

The resolve the community showed (while remaining, in the lingo, “non-hierarchal”) during the Junk Blockade seems absent in the current paralysis over Pusher Street. Christianites are not a small bloc: there are more than 700 adults and 200 children living on the 84 acres. But there remains a deep sense of powerlessness against the gangs that control the drug trade and, in large part, form Christiania’s public image. Residents I spoke to mostly wanted to avoid the issue. “I don’t want problems,” was a common refrain in refusing to talk about the gangs.

(More on Roads & Kingdoms: Prayers and Politics in Rangoon)

Pusher Street is the first face of Christiania, the place where the Bådsmandsstrædes gate dumps visitors. Pusher Street, as such, is a lousy welcome center. It’s not just the sullen drug dealers, it’s the entire buzz of the place: fragile, illegal, guarded. The “No Photography” signs seem logical, but in practice serve mostly to intimidate visitors, because numerous court cases have shown that Copenhagen Police have sophisticated and unblinking surveillance of everything and everyone on Pusher Street. As one recent visitor pointed out, the signs saying “No Running” are even more telling: the mood of Christiania around Pusher Street is so illicit and paranoid that one person running might just trigger a mass panic. Police raids have been an integral part of the long life of Christiania: the last mass raid and dismantling of Pusher Street was back in 2004, but the street feels ready for trouble.

This edginess wouldn’t stand out as much in Madrid, Paris, London or Europe’s other more fractious capitals. But central Copenhagen is a studiously pleasant place. The orderly bike lanes, softly lit canal streets and clean-swept sidewalks stand in direct contrast to beady-eyed Pusher Street.

But perhaps the biggest contrast is between the anarchic, organic structure of Christiania’s best ideas of itself and the rigid top-down structure of Pusher Street. Nine months of Copenhagen Police surveillance, later published in court findings in 2004, offer an inside glimpse of the hierarchy of the drug trade. Drug policy researchers, particularly the Danish academic Kim Moeller, took up the documents in search for insight into how the illegal drug trade—well researched in its street forms throughout the western world—would behave when there was, for all intents and purposes, no threat to the marketplace.

Some of Moeller’s best research compared Pusher Street with the street-level sales in Lithuania Park on the other side of Central Copenhagen. The primary innovation of Pusher Street, writes Moeller, lies in its “complex social hierarchy” that both determined who got the prime selling spots and organized an “aggressive and disciplined” team of lookouts that worked for the entire collective. Where normal street-level dealers might each have to employ their own lookout, the some 40 or so vendors have a communal team of lookouts who work in shifts of up to 12 hours and make about 16 euros an hour. The stability of the market also meant that unlike vendors in Lithuania Park, who had to offer sales and rebates like “five joints for the price of four”, Pusher Street kept its prices steady, and its costs down. Moeller reports the average cost per hour of being a drug dealer in Pusher Street was 30 Euros per hour versus 49 Euros in Lithuania Park, though the take-home pay was roughly even, a median of 325 Euros per hour for the owners of the stands on Pusher Street, 369 Euros an hour for those who sold weed in a public park like Lithuania.

The pricing was hard to compare, noted the academic, because of the inability to really control for quality. That is, weed is more expensive in Christiania, but it’s also, empirically, dense and purple and mind-blowing, so it could be a better value. The undisputed advantage of the Pusher Street market for consumers is in the variety. The dealers in Lithuania Square offered one kind of hash and one kind of weed. On Pusher Street, the average dealer tempts with up to a dozen kinds of hash and three or four different strains of weed. All of these differences, says Moeller, come from the stability of the de facto legal market.

The raid that followed all of this police surveillance was no small disruption to that stability. Police in full riot gear swept into Christiania on April 16, 2004. They tore down 37 booths, arrested 60 dealers and almost the entirety of the 20-person lookout corps. They confiscated millions of kroners and won nearly 60 convictions.

For a time, at least, Pusher Street was dead. But that big bust was followed by indecisiveness from the central government. Although there are occasional roundups and stings, there have been no large-scale sweeps since 2004. “The hash trade today is just as open as it was in 2004 and up on the same level. We believe that a billion kroner is sold every year,” a police official told Copenhagen’s Berlingske newspaper recently. There’s dispute about the effect that the crackdown had on the rest of Copenhagen. Even Venstre’s Lauritzen admits that the drug trade outside of Christiania took off after the raid, though he says the police action wasn’t to blame. “I believe it would have been spreading out anyway, to be honest,” he says. “It’s a matter of opinion, not fact.”

As Christiania hurdles toward normalization, though, the ugliness of the Free Town’s underside is not going away. Petty theft seems to be a constant concern. On an afternoon walk through the residential warrens of Christiania, I came across a sloping lakeside shack that had a single plea written in halting English on a post-it note in the window: “Don’t steal from me anymore pleace! I am poor to.”

And then there’s the violence that billows off of Pusher Street. The latest victims would seem to be meter maids. Parking is one of the unintended problems of modern Christiania—the commune is closed to traffic and parking, so the cars of all those who live and work there have been clogging the streets of the Christianshavn neighborhood outside. For most people, this is merely a nuisance. For the young men of Pusher Street, it’s an incitement to violence. In January, reports the Copenhagen Post, several uniformed officials were issuing parking tickets on a Friday evening “when eight to ten men wielding clubs ran out of Christiania and attacked them”. The article noted that parking enforcement officials undergo “conflict management” as part of their training, and that this was of no use to them when faced with a gang of club-wielding drug dealers.

The question now, however, is what happens with Pusher Street in the new era of Christianites owning their land. For Venstre, which had been frustrated with the resilience of the drug trade behind Christiania’s gates, the changes present an opportunity. “Our solution is to start normalization on the first of July,” says Lauritzen, the conservative MP. “And then I have a strong belief that the police will be more aggressive.“

Christiania has never, however, seen the Pusher Street problem as a failure of aggression. In the early Christiania documentary, one tour guide was on film leading a group to Pusher Street to talk about the drug trade, just as a group of undercover cops came rushing past and, in the background, began beating drug dealers they were arresting. “The more terror the police use on Pusher Street,” the guide told the camera later, “the tougher the street becomes.”

Who Gets to Stand Where

Prior to his retirement this month, Pitzer College professor Dana Ward maintained an online archive of anarchist theory and history. The Anarchy Archives are, in one sense, a memorial: one common trait of the various movements is that they failed, often spectacularly. The Paris Commune ended after just a few days in 1871, with up to 50,000 communards executed or sent to exile in Micronesia. Nestor Makhno commanded an “anarchist army” of up to 110,000 soldiers and held the sprawling Free Territory of southern Ukraine for four years, but had to submit to the Bolsheviks in 1921. Revolutionary Catalonia borrowed many of Makhno’s tactics and lasted only three years during the Spanish Civil War. Before and after all of these came hundreds of smaller communities, communes, squats and collectives that have sought to build new societies apart from the old. And they, too, have dissolved or been forcibly disbanded.

I asked Ward whether Pusher Street, rather than normalization, would be the death of Christiania. ‘It’s a mistake to think that utopian anarchism is a form of perfection,” he says. “There’s always going to be a problem, a threat. The question is how are you going to deal with them? With violence, hierarchically?”

He said that drugs may be the wrinkle in Christiania, but that “anarchist communities are almost always going to be in violation of rules.” In the 19th century, American movements were bedeviled instead by issues of sex: the Oneida anarchist community never quite survived its adherence to complex marriage, to take one example.

But for Ward, the real problem at Christiania is the same one that tangled Paris and the Ukraine and Catalunya. “The big issue between anarchists and the state is contestation over space,” he says. “It was the same with Wall Street and the Occupy movement. It’s all about who gets to stand where. Where is there space to be free?”

Increasingly, it looks like the Danish government does not think that central Copenhagen offers that kind of space. The Christianshavn neighborhood is one of the jewels of Copenhagen now. Noma, the acclaimed Best Restaurant in the World, where dinner will set you back more than $250 a head, is a five-minute walk from Christiania proper (to make extra money on the side, Fox collects wildflowers and greens on her woodland walks and sells them to Noma and other well-heeled neo-nordic restaurants). The apartments just outside of Christiania are now “hilarious expensive”, as Fox put it. Rumors abound of nefarious developers eyeing Christiania’s property, and the communal structure of the land purchase—a single fund to buy all the houses, instead of individual ownership—serves in part to prevent individual Christianites from selling their own plots to developers.

For conservatives, Christiania started as, and remains, a crime of real estate. “It’s a question of principle, whether a group of people should be allowed to occupy a large part of government property in central Copenhagen,” says Lauritzen. “There’s no question that what they’ve been doing is illegal… they seized government property and have been living on it and that’s worth a lot of money now.”

That raises a question: why have the Danes tolerated Christiania for forty years while the NYPD could barely tolerate Zucotti Park for forty nights? In the 1980’s, American journalist Richard Eder visited Copenhagen and found the de facto standoff over Christiania a symptom of modern Danish fecklessness. He found his counterpoint at the base of the nearby statue of Archbishop Absalom, outside of Christiania: “The Archbishop, who fortified the town in 1167, is astride a horse, and he carries a battle-ax. The Danes have not been like that for a long time. More recognizable is the statue of Hans Christian Andersen across town. He sits on a bench, head cocked attentively, and thinks wrinkled thoughts.”

The wrinkled thoughts that come from Lauritzen and his liberal and conservative colleagues are thoughts of compromise. He sees normalization as a sort of unprincipled, but necessary, amnesty for the ur-crime of seizing property. “We are going to look the other way,” he says, in exchange for accepting the deal. “That’s a Danish compromise, a very Scandinavian compromise, that would not happen in other countries, of course.”

Fox remembers that first occupation, when her Danish mother brought Fox and her sister to Christiania. Fox’s mother had already broken up with Fox’s American father, and they just climbed through the gates to start a new life inside. “It was very different then because all of the houses were empty,” she says, “and if you saw a house that you liked, you could just sort put a sign up that said ‘occupied’.”

“In the beginning, people wanted to do everything together,” says Fox. “They would eat together, sleep together, wear the same clothes. Everything was shared. They were experimenting a lot with, umm, not having any limits. I think they came from very strict house rules and had been brought up very strict. And suddenly they gained all this freedom here, and they just went crazy. They couldn’t control anything. So in that way it was very difficult. I wasn’t always sure when the next meal was coming. It wasn’t always nice.”

And yet, when Fox came of age, she decided to raise her children in Christiania. “I thought it was nice to have them near the trees and the water and a canoe and a horse, and also near the city where there’s life and places to be educated.” Whereas she and the other kids of Christiania had often been ridiculed in the schools they attended outside of Christiania, by the mid-80’s Christiania had its own school inside and more acceptance on the outside. And she raised her son and daughter with a touch of the bourgeois parental rulemaking that had been lacking in her own childhood. “I wanted to have some control of what was going on with the kids,” she says. “Eight o’clock was time for bed, we ate at six.”

The ideal of Christiania, however, did not dim for Fox. She still calls herself an anarchist and still believes, on good days at least, that living the “political life” of a Christiania resident is a special privilege. That belief has become her day job, in a sense. The government is offering to sell Christiania—except those small parts that are under environmental protection—to its residents for 76 million kroner (the real value could be as much as 20 or 30 times more than that) and it’s up to Fox and the other Folkeaktie staffers to sell enough shares to cover those costs. The shares, which come in denominations from 100 kroner up to 50,000 kroner, are not an actual stock issuance. Owning a social share in Christiania affords you no special privileges, no property, no voting rights. They are, in some sense, simply a show of support for the idea of Christiania.

I met Fox on one afternoon in her office, as she was selling shares to an affable and somewhat weatherworn Christianite named Martin (“I usually pay for things with happiness,” he says, “but today I’ll use a credit card”). Fox told me that the people who have bought shares—including over a hundred people who bought online from the United States—have wildly different reasons for their purchase:

People buy it because they have an idea of the place, some people buy it because they’re nostalgic and when they were young they were out here smoking a joint or some people who saw their first rock concert here. Some buy it to give it to their really conservative uncle as a hate present, some buy it because they really believe that this is the place for freedom, some buy because they want to be romantic and show their girlfriend that they want to set her free but that they still love her anyway.

Converting that romance into the full 76 million kroner remains a challenge, however. To date, Christiania has sold less than nine million kroner (about $1.5 million USD) worth of shares, and the fundraising thermometer on their website “doesn’t look good”, as Fox puts it. A recent op-ed in Berlingske, a national newspaper, focused on the slow progress with the snide assessment that “Freetown Christiania is apparently not as popular as Christianites thought” and suggested that the shares were a ruse. “They are really just indulgences and not real shares,” the author wrote. “It’s unclear why authorities have not intervened against the misleading marketing. Potential buyers, however, smelt a rat and stayed away—without official help.”

(More from Roads & Kingdoms in Denmark: Benny Andersen, Oysterman)

On this point, however, even the conservative Lauritzen is supportive of the Folkeaktie and Christiania’s potential to meet its obligations. The government is backing loans to cover any amount that is not raised by the Folkaktie, and based on that backing, banks have lined up to lend the rest of the money. “I’m pretty convinced that what [Christiania] has promised, they’re going to live up to that. Because they’re getting a really big bargain, “ he says. “They’re capitalist enough to know that this is a one-time offer.”

Touristiania

In the mid-1960’s, on a stretch of uninhabited ranchland in Colorado, a collective of artists started one of the first hippie communes in the U.S. They called it Drop City, and while there were a number of reasons for its failure two years later, one of the major reasons is rather neatly captured in a hand-painted sign they put at the entrance of Drop City. The sign, which appears in Mark Matthews’ book Droppers, simply says: Limit One Question Per Visitor.

Of all the external pressures faced by alternative communities, perhaps the most unexpected is curiosity. Drop City, like Christiania, both courted attention for its social innovations and then wilted under the pressure of the many visitors who wanted to come see the place for themselves. In Christiania, even in the early 80’s, when that first documentary was shot, one of the residents complained to the camera about “playing the buffoon”, the ceaseless need to explain Christiania to leering, voyeuristic outsiders who came to poke around.

(More from Roads & Kingdoms: Cusco, Unplanned)

Christianites are still playing the buffoon, but now they have to do it for up to one million visitors a year, a staggering number that makes them the number two tourist attraction in all of Denmark, just behind Tivoli Gardens. Tour buses line the streets outside, and many residents make their livings as guides. The groups are unmistakable, elementary school field trips and gaggles of retirees, clustering in front of the general store, peeking into the workshop of Christiania Bikes (whose cargobikes have now been trademarked in the U.S. and be bought for $3000 each in Soho in New York). It’s unsettling enough that some neighborhoods, like the Dandelion enclave where Fox lives, have instituted strict rules about when visitors can come. No tourists after 4pm.

The tourism trade has created a casualty in Fox’s own family: she had dreams of having her teenage children be the third generation of her family living as adults in Christiania, but Fox’s daughter Quri has already decided that the she can’t live in the middle of a tourist attraction. “She doesn’t like people looking through the windows and she feels like an animal in the zoo,” says Fox. “I can really understand.”

If they are a nuisance, however, those visitors are also a source of protection. Lauritzen’s party sees tourism as an important silver lining for Denmark. “We can’t stop it, so let’s try to make some money out of it, let’s try to accept it and create a tourist attraction.” Residents also understand that Christiania’s status as a tourist destination probably saved their homes from the bulldozers over the years: even in the early days, there would have been too many outside witnesses to that particular form of murder.

Tourists aren’t the only visitors, of course. There are also the journalists. They’ve been coming since the first day. Adhering to the rules of pack journalism, the coverage often has a news-of-the-weird quality: Aging hippies! Coed showers!

This is a shame, because it would seem like there is a deeper meaning to Christiania, its stature and its survival. Maybe it’s something about the valor of resistance, or about the almost-childlike insistence on playing by your own rules. On my last night in the Free Town, I went with a couple friends in search of some kind of answer, and we went to the most obvious place for quick enlightenment: Pusher Street. The joint we bought was so scientific and lab-powerful that it came in what looked like a test-tube. We bought beers and then smoked on the benches at Nemoland, and I shot straight past Epiphany and right into High as Fuck. As my companions talked about Noma and In-N-Out burgers, I mostly just stared in the middle distance, my mind swimming in silence trying to reach some far shore. Around us were clubbers and druggers and the alcoholics who had come over from their nest across from the general store. It was 3am, and around me Christiania was starting to swim, ever so slightly, along with my mind, tilting and surging. And there was, I guess, the thought I had been waiting for: Christiania is moving. Always moving. And though normalization may be a despised process, and July 1 a day of mourning, the best of the lot at Christiania understand the inevitability of change. The day these 84 acres stop changing, Fox told me on that first day, is the day they’re no longer alive.