A Brazilian family discovers one of the world’s largest mass grave of enslaved people in their backyard.

In September of 1996, Merced Guimarães was thrilled to finally start remodeling her house in Rio de Janeiro’s old port area. She and her husband had saved up for years to be able to redo their fixer-upper.

But when the construction workers finally broke ground in the backyard, it looked like they were headed for another delay. As they came into the house for a midday meal, the workers told Guimarães that her yard was full of animal bones.

That’s strange, she thought. After lunch, she went to check it out. There were small bone fragments everywhere in the dirt the workers had dug up. One caught her eye and she bent down to pick it up. It was a fully intact jawbone, with a row of teeth still attached. “This isn’t a dog,” she said. “These are human bones.”

Guimarães called the police. Her first thought was that a family had been murdered there, but looking at just how many bones there were, her imagination jumped to a serial killer who grabbed people in the narrow alleyways of the historic neighborhood. One of the construction workers got spooked; he left and never came back.

Later that evening, it occurred to her that the crime committed on her property might have been even worse than the serial killer she had imagined.

She remembered that some years before a friend from the neighborhood homeowner’s association had mentioned there was a forgotten slave cemetery somewhere nearby.

She called him and he came over and they looked at available 18th and 19th century maps. While the maps were inaccurate, there was no mistaking it. They had rediscovered a dark reminder of Rio’s days as the world’s largest slave port. The workers had inadvertently discovered the largest known mass grave for enslaved people in the Americas.

After completing the Middle Passage from Africa under horrendous conditions, many enslaved people died upon their arrival to Rio de Janeiro, the capital of the Portuguese colony of Brazil. Some 20,000 to 30,000 people were buried at the port, under what became the Guimarães’ neighborhood.

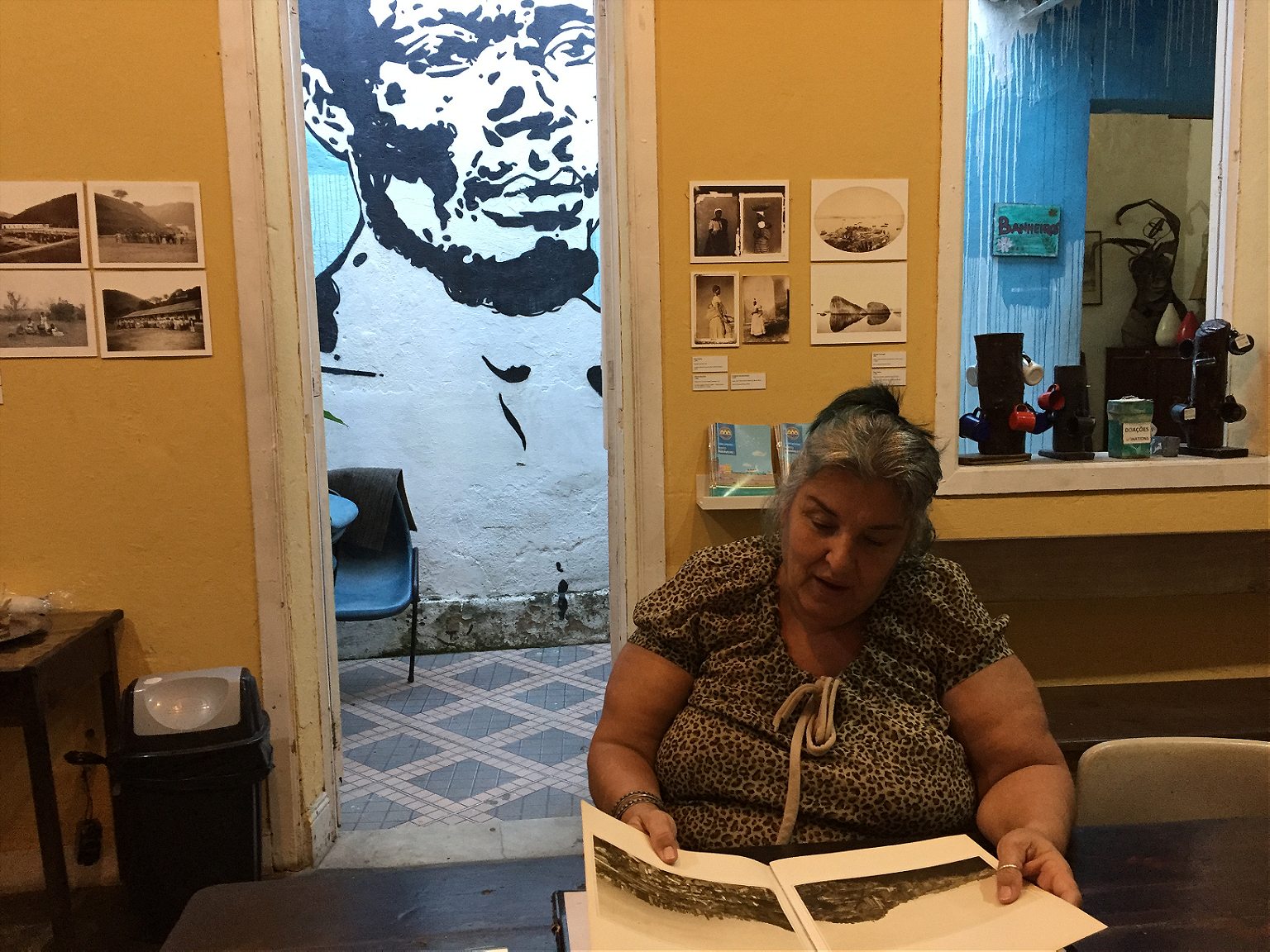

“That’s when the saga of the New Blacks Institute began,” says Guimarães. After she alerted the city government, she had expected an outpouring of interest. But after an initial excavation, the city never came back.

“I was confused,” says Guimarães. “Why wasn’t this place being taken care of? But the truth is that the authorities built these houses over this cemetery in 1866—it’s a way to forget, to put a lid on it,” she says. “They had no interest in keeping this memory alive and in the modern day, they still don’t.”

Then, an ally at the Ministry of Culture began to share the story with local media outlets and soon journalists came knocking at their door. Others followed suit: researchers, university professors, historians, students, curious people.

“We had no idea what we were doing, people would just come knock on our door and we would receive them in the evening with a pot of coffee. They told us what they know, and we told them what we know,” she laughs at the memory. Her teenage daughters hated the constant flow of strangers in their home. She recalls one group of students who knocked on her door at 5 p.m. and left at 2 a.m.

After gathering so much information, they started a website to share it all in one place. “Then things only got worse from there,” she says jokingly. “People went to the website, they learned the story, and more, and more and more people came to our door.”

Guimarães, a daughter of Spanish immigrants who worked in the pest control industry, found herself far out of her element.

“I really didn’t have anything to do with this world. I never studied these things—I’m not an anthropologist, or a sociologist or a historian,” she says. “I bought a house with bones under it and I was curious. It was my civic duty.”

Beyond civic duty, Guimarães says she was spurred on by the fact that few officials seemed to want to know about the graveyard, or the people who were buried there. “What brought me here to fight for them was that nobody wanted to even know about them, and they still don’t want to know about them.”

“I confess we didn’t have any idea what to do or how to do it, but we knew we had to do something,” says Guimarães. It was like going down a rabbit hole—she started looking in, and the further she looked, the deeper she was in, and the harder it was to get out.

The family were confronted by many problems along the way. Guimarães claims that in the first five or six years after the discovery, the government constantly promised to do something with the land, but officials never explained what they planned to do.

“The city government wanted us out of there,” she says. “They didn’t know how to deal with the fact that a family lived above this cemetery and was sharing the story of what happened there with the world.”

Guimarães says she thought the city government just wanted the story to go away, and the family to stop telling people about it. “The truth is they wanted to end what we were doing here. Because this cemetery wasn’t just our house, it’s under four or five different houses. But we were the ones who were making the story of this area known.”

The city ordered them to put their renovation on hold, but suspended in the middle of construction, the house wasn’t safe to live in. The Guimarães family—the couple, their three daughters, plus their dog, cat, and parrot—had to move into the offices of their pest control company. The experience was incredibly taxing, Guimarães says, but once they realized the government wasn’t coming back, they restarted the remodeling and moved back in.

The couple decided to go ahead with plans to expand their property. They bought the two run-down homes next door, with hopes of making a garage and expanding the yard. At her husband’s suggestion, they decided to start receiving people who were curious about the graveyard in the garage.

The couple started putting photos and artifacts up on the walls, and they made a long wooden table for visitors to gather around. Their home became a makeshift museum.

In 2005, a friend of the family applied for a grant to make it official. This marked the opening of the Instituto Pretos Novos, or the New Blacks Institute, a tribute to the people buried there, who as recently enslaved Africans were called ‘new blacks.’

On a recent day in May, archeologists from the National Museum of Brazil were excavating. While the city government were still offering little support, countless academics and researchers have discovered a great deal about the graveyard.

In a square hole in the ground inside the museum, they had found an almost completely intact skeleton. Andrei Santos, an assistant for the two lead archeologists, was squatting over the body.

“There’s more here,” he says, pointing to the body’s surroundings. “But I’m afraid if we do too much in this area it’s going to move her and break her.”

“What happens is that we start excavating and we find another, and another. That’s how we found her,” supervisor Nelson Mendoça explains. “We were excavating above her and we came across her teeth, perfectly intact, so we kept going. Looking at this now, I would say there are bones from at least three people in that square around her.”

Many of those buried were children

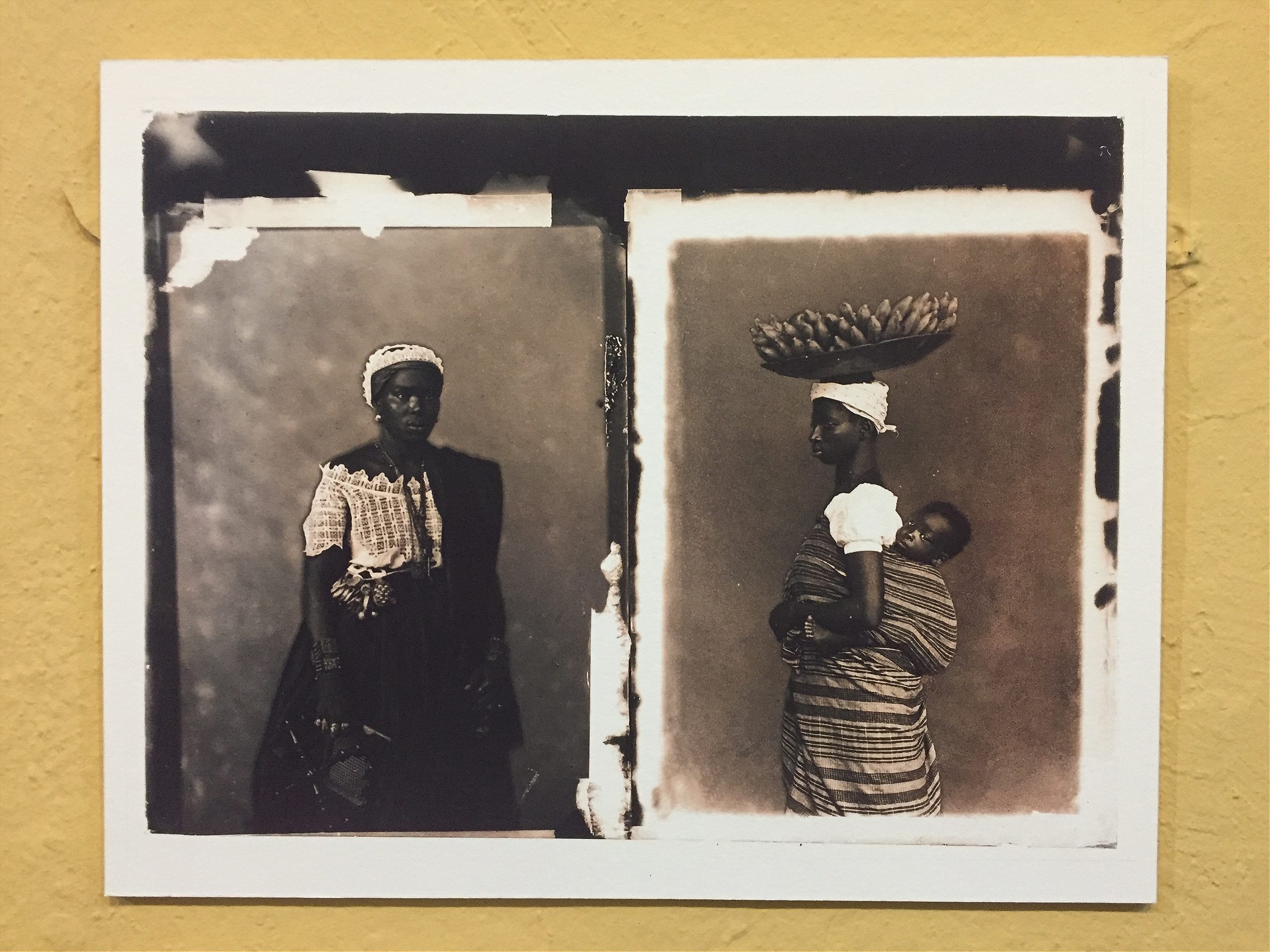

Historians, archeologists, and other researchers discovered that the bodies buried in the graveyard were burned. Many of those buried were children. They were mostly of Bantu origin and examinations revealed that many had filed teeth, a common practice in Angola. They were buried with rings and necklaces typically worn in Southern Africa at the time.

This cemetery, once part of a bustling port and slave market, was covered up in an attempt to hide the horrendous atrocities that happened there. These crimes are slowly being unmasked. In 2011, construction for a neighborhood development project came upon the Cais do Valongo, the Valongo Wharf, where enslaved people disembarked from the ships.

The docks stopped functioning in 1831 when the trafficking of slaves was outlawed. However, slavery itself was still legal and a clandestine slave trade continued until 1888. The disused wharf was covered by landfill in the early 1840s.

The docks were covered by landfill after the slave trade ended in 1831. The Valongo Wharf gained UNESCO World Heritage status this month, the organization calling the site, “the most important physical trace of the arrival of African slaves on the American continent.”

After the slave trade ended, the port neighborhood became the heart of the African community known as Little Africa. It’s home to cultural gems like the Pedra do Sal, or Salt Rock, a giant slab of granite that forms a hill and is a hub for samba music, where free samba sessions are still held weekly. These sites are on what has since been dubbed the African Heritage Circuit.

Despite its part in the neighborhood’s heritage, the New Blacks Institute is under threat. They were receiving funding from a development initiative in the neighborhood, which was cut at the end of 2016. Guimarães says they have no public funding now and are barely able to get by on donations from friends and visitors. She estimates that they’ve only got enough money to keep their doors open until August 2017 if they don’t get any financing from the government.

Guimarães says city officials have told the New Blacks Institute that with a nationwide financial crisis, the city can’t afford the $2,000 a month the institute needs to keep their doors open. Guimarães points out this is a relatively minuscule cost in comparison to recent revitalization efforts ahead of the 2016 Olympics, which were in the same neighborhood, and included a $2.5 billion investment in new plazas, pedestrian walkways, a museum, and a $380 million tram line.

A representative of the city’s culture ministry says they will help, and that they’re developing a project to revive Rio’s African legacy that includes the institute, but that budget decisions are still being made.

Brazil has the largest African diaspora in the world

Sadakne Baroudi, an American historian who gives Afro-Brazilian walking tours in the neighborhood, says that financial support is the least the government could do. “Operational cost of the New Blacks Institute is the tiniest of obligations for what happened in this city,” she told the website RioOnWatch. “It was the largest slave port… Does Auschwitz have a GoFundMe page?”

Of the 10 to 12.5 million Africans enslaved and brought to the Americas during the slave trade, about 4.8 million landed Brazil. That’s about 10 times the 500,000 or so that were taken to the United States. Today, over half of the nation’s 200 million people identify as mixed-race or black, which means Brazil has the largest African diaspora in the world.

African influence on modern day Brazilian can be seen in food like moqueca: a fish stew made with coconut milk and palm oil; and acarajé: fried bean patties stuffed with a spicy paste made of coconut, peppers, and shrimp.

Brazil’s drum-heavy samba music stems from South African percussion traditions and many researchers believe the word samba itself is derived from the Bantu word semba, which refers to a kind of traditional music from Angola.

Despite African influence everywhere you look in Brazil, the country’s troubled past and the complexities of modern-day race relations aren’t fully acknowledged.

The massive revitalization efforts in the region before last year’s Olympics, for example, hit a familiar nerve for black activists in Rio, who saw it as another example of black history being pushed aside.

Ronilson Pacheco, an activist, wrote: “It disturbs my own history, and my historical consciousness, to know that a black past is deliberately ignored and destroyed so that a white, middle-class future can be erected in its place with celebration and pageantry.”

Guimarães says people in Brazil haven’t realized the far-reaching consequences of the country’s slave trade. “People know there was slavery but they don’t connect that it’s a horrible crime and that the large majority of the population today survived this crime against humanity,” she says.

“Africans were able to protect their culture and you can see that in a lot of ways today in Brazil, although most people here think of these things as Brazilian.”