The customer was never right at Abu Adel’s legendary south Lebanon restaurant.

Fava bean stew, or ful medames, isn’t just a dish. It’s a culinary ritual. The mashed beans are flavored with garlic, lemon juice, and olive oil, then garnished with diced tomatoes and parsley. Usually served as part of an elaborate spread, the resulting fragrant stew is scooped up with freshly baked pita bread.

When I was growing up in the southern Lebanese port city of Sidon during the nineties, ful was ubiquitous. We ate it for breakfast, lunch, supper and even sohoor, the pre-dawn meal during Ramadan. My five siblings and I sometimes consumed the dish more than once a day.

The frequency with which we ate ful was partially down to tradition. In Arabic, the dish is described as “the wealthy man’s breakfast, shopkeeper’s lunch, and poor man’s dinner.” The saying underlines the extent to which ful’s appeal cuts through class and borders in the Arab world.

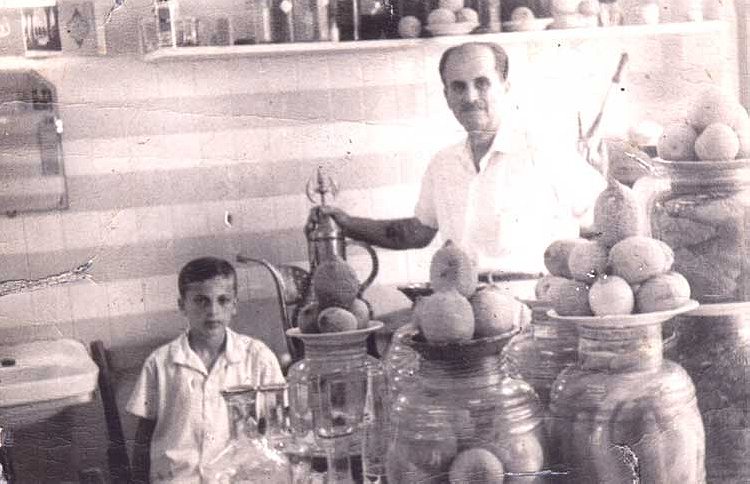

But ful also holds a special place in my family. During the 50s, 60s, and 70s, my late grandfather, Ahmed Mustafa Hankir, ran Ful Abu Adel. It was one of the most popular ful restaurants in Sidon, perhaps even south Lebanon. Wealthy or poor, Palestinian refugee or Lebanese politician, Muslim or Christian, it didn’t matter. All kinds of Sidonians flocked to the ful restaurant first thing in the morning.

Abu Adel was king at his restaurant. The customer was never right. If someone so much as suggested how they wanted their ful prepared, jeddo (my grandfather) would say, “Eat to my taste, not yours,” or sometimes: “Don’t talk, just eat.” If the guests didn’t appreciate his somewhat rigid approach, he’d tell them they were welcome to go across the street to dine with the Soussis, his competitors. Sidonians described Abu Adel as sarbast, a Turkish word meaning unreserved and bold.

To many, my grandfather’s name—Abu Adel (which means father of Adel)—conjures images of Sidon’s glorious past, its old souk and cafés. That was before the Israeli invasion of south Lebanon in 1982, during which the army captured Sidon as it advanced toward Beirut. Fierce urban combat damaged parts of the city and temporarily shuttered some establishments.

Abu Adel is said to have prepared, served, and eaten ful almost every day of his life from 1918—when he was 16—to 1980, two years before he passed away. He only shut the restaurant on the first days of Eid al Adha and Eid al Fitr, and that was mostly to mark the Muslim holidays with prayer, rather than to give himself a break.

On the weekends, American University of Beirut students would come from the capital to dine at jeddo’s restaurant, which was also renowned for its cleanliness. Abu Adel is said to have quipped with the students when he had a spare moment, telling them they weren’t just eating ful, but masameer el rekab (screws for the knees), a cuisine that would keep them strong, like livestock. The students paid Abu Adel generously—the additional income was enough to allow him to feed neighborhood orphans for free, and to support his 14 children.

Other patrons at the restaurant included the late Rafiq el-Hariri, former prime minister of Lebanon, and one of his successors, Fouad Siniora, who both visited Ful Abu Adel when they were still students at a nearby school. Jeddo’s reputation traveled far and wide. Prior to opening up shop in Sidon, he lived in Haifa, where he ran his first ful restaurant. Legendary Egyptian singers Umm Kulthoum and Mohamed Abdel Wahab were said to have dined there during tours of Palestine.

I never met my grandpa—he died before I was born—but I’ve learned about his legacy from Sidonian ful sellers. “Your grandfather,” the ful veterans say, “was the king of ful. The teacher of all teachers.”

Jeddo was born in Sidon in 1902; his mother passed away less than two years later from an illness. Around the same time, his father set off to fight with the Ottoman Empire against the British Army in Yemen, and wouldn’t return until more than a decade later.

Abu Adel learned early on that he would have to fend for himself, and ful would become the most important part of his survival story. He learned the basics of how to make the dish from a family in Sidon who offered him work when he was still a boy.

It was in Palestine that my grandfather started to make a living from ful. Jeddo emigrated to Haifa in 1918, joining his aunt who’d rented a derelict building in the city to shelter Sidonians who moved there seeking work.

Jeddo’s first business partner was a donkey

That same year, Haifa was seized from the Ottomans by the British. Under the British mandate, (with the help of a branch of the Hejaz railway, which opened under Ottoman rule) Haifa prospered, serving as the gateway to Saudi Arabia. The city was often referred to as Amerka el ‘areebe, or ‘nearby America.’ Many Lebanese moved there for economic opportunities.

Jeddo’s first business partner was a donkey. Abu Adel would prepare ful overnight, and scoop it up into containers he’d dangle from one side of the donkey (the other side was reserved for hummus). He’d then travel to neighborhoods along unmarked roads in and around Haifa to sell it, among them the villages of Hawasa and Balad al-Shaykh.

As a young man, Abu Adel was famously handsome. He had a rakish mustache and was rarely seen without his fez. People in the neighborhoods he frequented called him bayaa’ el ful, the ful seller. With time, he established a roster of loyal customers who’d bring their own bowls, into which Abu Adel would ladle his ful.

Jeddo sold ful from the back of the donkey for a decade, until he saved up enough money to buy land for a home in Haifa. Finally, in 1928, he opened a ful shop on al-Muluk Street (also known as Stanton Street) in Haifa.

In 1948, Abu Adel was expelled from his home during the Battle of Haifa and forced to join the Palestinian exodus, which saw him flee back to his hometown Sidon with his wife and children. There, he rebuilt his life from scratch, eventually opening another ful restaurant.

When my grandpa moved back to Lebanon, he left everything he owned in Palestine behind. He took only two suitcases he filled with Palestinian pounds, wages he’d accumulated from his ful business. When it became clear that the family would no longer be returning to Palestine, he used the money to set up shop in Sidon.

Abu Adel would wake up at the break of dawn to start his work days, taking along two or three of his seven sons at a time. My father (who was born in Sidon in 1948, months after the family fled Palestine) was frequently one of them.

Each son was responsible for a different task while jeddo went to the vegetable market. One would peel onions, crush the garlic with a mortar and pestle and pick the mint leaves from their sprigs; another would strain the beans—nearly 60 pounds of them—after they’d been left to cook in a copper pot overnight. The third son would collect salt and kerosene from a market.

Abu Adel was so hands on that instead of buying pickles, he made them himself

My father and his brother Nabil would often head to the beach after the copper pot used to cook the ful had been emptied. They’d clean it with sand, stones, and lemon juice. The urn, my Uncle Nabil says, would only be deemed clean by Abu Adel if it was shining.

During the days, the sons would wait tables under their father’s watchful eye as he cooked and prepared the dishes (Abu Adel was so hands on that instead of buying pickles, he made them himself). In the evenings, the sons would clean plates and utensils and mop the floors with their father. Most days, they wouldn’t get home until 8 p.m.

To help pass the time as they worked, my grandfather played recordings of verses from the Qur’an from a large radio. Abu Adel was a pious man, and by the time he passed away, his head had met the ground for prayer so many times that he had a noticeable mark on his forehead, known in Arabic as a zbiba (raisin), a sign of religiosity.

The word medames is of Coptic origin, meaning ‘buried,’ probably referring to the beans being cooked in a large urn. Colloquially, medames is commonly understood as meaning ‘stewed.’ While some trace ful back to Pharaonic Egypt, according to Gil Marks’ Encyclopedia of Jewish Food, the earliest evidence of the food is a stash of dried fava beans found at a Neolithic site near Nazareth.

Though ful recipes vary, preparation techniques are universally laborious. Beans are soaked, then heaped into a large pot, known as a qidra. They’re brought to a boil, and left to simmer on low heat for at least eight hours, usually overnight. In their final form, the beans are brown and soft enough to be mashed.

The basic ful medames recipe includes beans, garlic, olive oil, lemon juice, and salt, topped with tomatoes and sometimes seasoned with cumin. In Egypt, the beans are crushed almost entirely, while in Yemen, they’re mashed to the extent that the final product resembles a soup.

Meanwhile, in the Levant, the beans are left somewhat intact, and are only partially mashed. The overlap between Levantine ful recipes is notable, with Syria’s being the most singular.

“If I had to choose one dish that brings the people of the Levant together, it would probably be ful medames,” says Lara Ariss, a Lebanese chef and author of Levantine Harvest. “A simple medley of flavors is combined to make the dish, but the result is profound as each ingredient has a voice of its own.”

The typical Sidonian ful spread is colorful and meticulous: pita bread fresh out of the oven, sliced tomatoes, shallots, pickles, pickled turnips, radishes, mint leaves, olives, onions, and, of course, olive oil. The assortment of ingredients brings flavor to an otherwise bland fava bean. Hummus frequently accompanies the dish, but it’s ful that takes center stage in this particular mezze.

Numerous Arab and African countries have absorbed the cuisine. The nations have given ful its own accents, with different takes on added ingredients. The Syrian spin on ful can include tahini and yoghurt, while in Yemen, green chili is sometimes added, giving the beans a hint of spiciness. These variations are reflected in Sidon’s restaurants. Each chef has their own take on ful, adding, for example, cumin, pepper paste, coriander, parsley, and even eggs.

Founded in 1933, Malek el Ful Soussi is one of Sidon’s oldest ful restaurants and a longtime competitor of my grandfather’s. There, the chefs use a combination of Seville oranges and lemon juice to give the beans a slightly sour undertone.

On a particularly hot Monday afternoon in Sidon last month, Malek el Ful Soussi seemed relatively busy. There were four families dining at the modest-sized restaurant. For four thousand Lebanese pounds ($2.70) guests got a generous plate of ful with pepper, pickles, olives, and other assorted vegetables.

The owner, 73-year-old Hassan “Abu Fadi” el Soussi, is one of Sidon’s most renowned ful connoisseurs. “I was born in between a bowl of hummus and a bowl of ful,” he says. “Ful has defined my life.”

Though many ful chefs have come and gone in Sidon, Abu Fadi said, none were quite like Abu Adel. “He once fought with my father over olive oil supplies,” he recalls, chuckling. “There was no one on his level.”

It is said that ful flowed like milk in Sidon in the 50s and 60s: there wasn’t a household that didn’t consume it. Ful in Lebanon is a family trade—Abu Fadi’s father, son, uncles, and brothers have all been part of the industry.

“People aren’t passing on the business like they used to, and competition isn’t as intense as it was when your grandfather was around,” Abu Fadi says. “I wish we still had that sort of competition. Today, the competition is from other foods,” especially fast-food joints.

In 1980, jeddo became too ill to work, and Ful Abu Adel was shut down. Today, in its place, stands a small grocery shop. Passersby will often refer to it as ‘where Ful Abu Adel once was.’

While Abu Adel’s sons learned some of the craft of ful-making from him, my grandpa was, perhaps, too proud to hand it off entirely, and wanted better lives for his sons. By the time he fell ill, it was too late to ensure the business would carry over.

When I ask my father why there was no concerted effort to maintain the family business, he says, simply, “It was too hard. No one could make ful like my dad, not even us.”

Top image: A bowl of ful medames. Photo by: Momen Khaiti