Crate-digging for a fading musical tradition in Haiti.

JACMEL, Haiti–

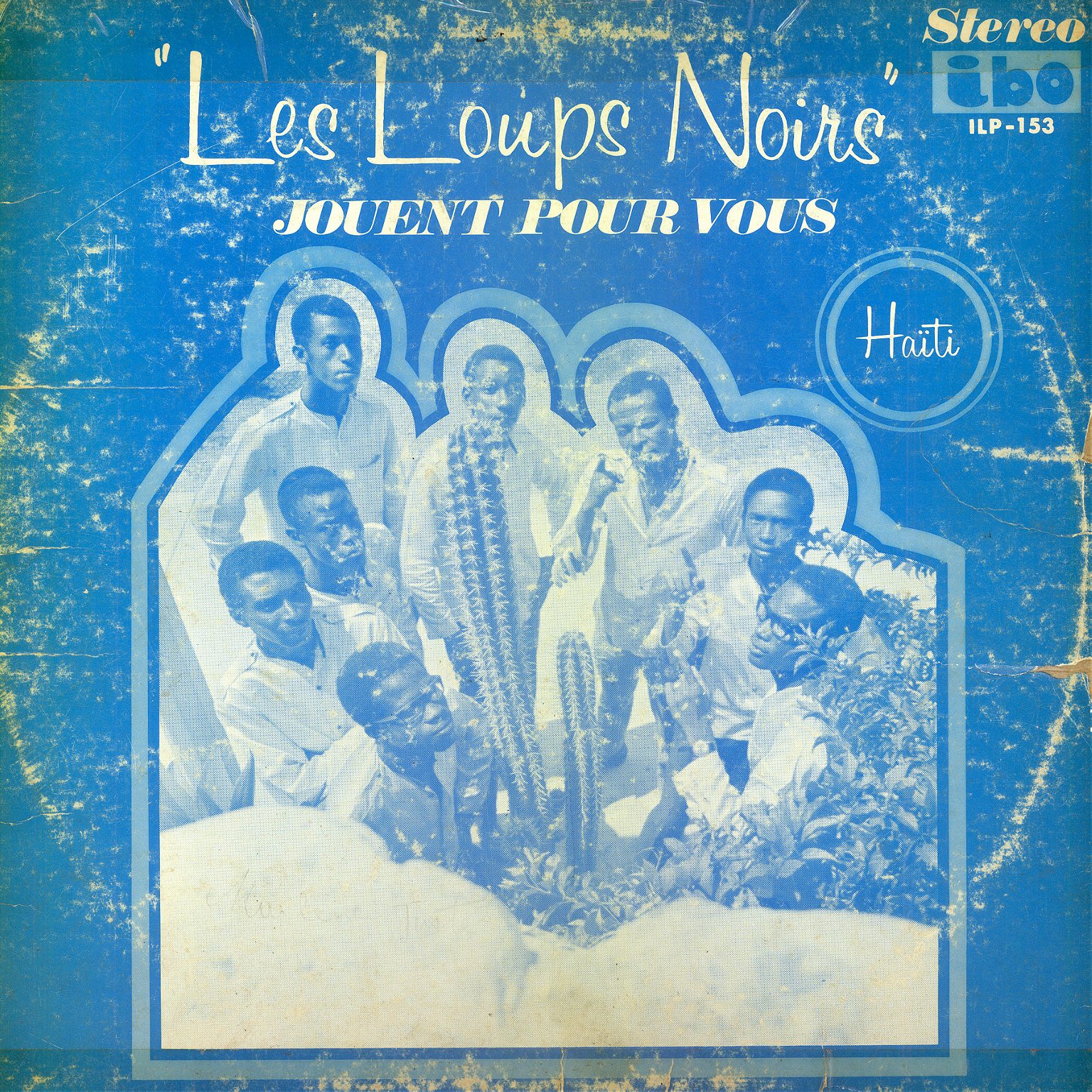

In Jacmel, a sleepy beach town on Haiti’s southern coast, I hit pay dirt: In the archives of a local radio station, stuffed inside a gray metal locker, were hundreds of rare vinyl records, relics of a golden age of Haitian music. I sorted and sifted for hours, previewed each record on my portable turntable, and then entered into lengthy and sometimes frustrating negotiations over cost. Among the stacks was a holy grail of Haitian music: The debut LP of Les Loups Noirs—The Black Wolves—titled “Jouent Pour Vous,” recorded in 1970 when the group was still in their early twenties. Les Loups Noirs became a key part of a rich musical tradition that few people off the island or outside the Haitian diaspora know exists.

I’d come to Haiti in search of rare and obscure Haitian vinyl records just like these, mainly from the 1960s to the ‘80s, in a bid to preserve, re-master, and compile them, and issue an anthology of the cosmopolitan Haitian sound at its experimental, revivalist best. During what crate-diggers and curators refer to as the “modern” or “golden era” of Haitian music, musicians experimented with traditional rhythms while balancing a host of outside influences. There was the jazz-era instrumentation, imported during the early twentieth century American occupation, which introduced horn sections to Haitian ensembles. From Cuba came meringue, mambo, son, guajira, and charanga. Accordion-driven Colombian cumbia and Dominican merengue left their marks as well. Added to the melting pot of sound were rhythms, drum patterns, and percussion brought across the Atlantic from Africa.

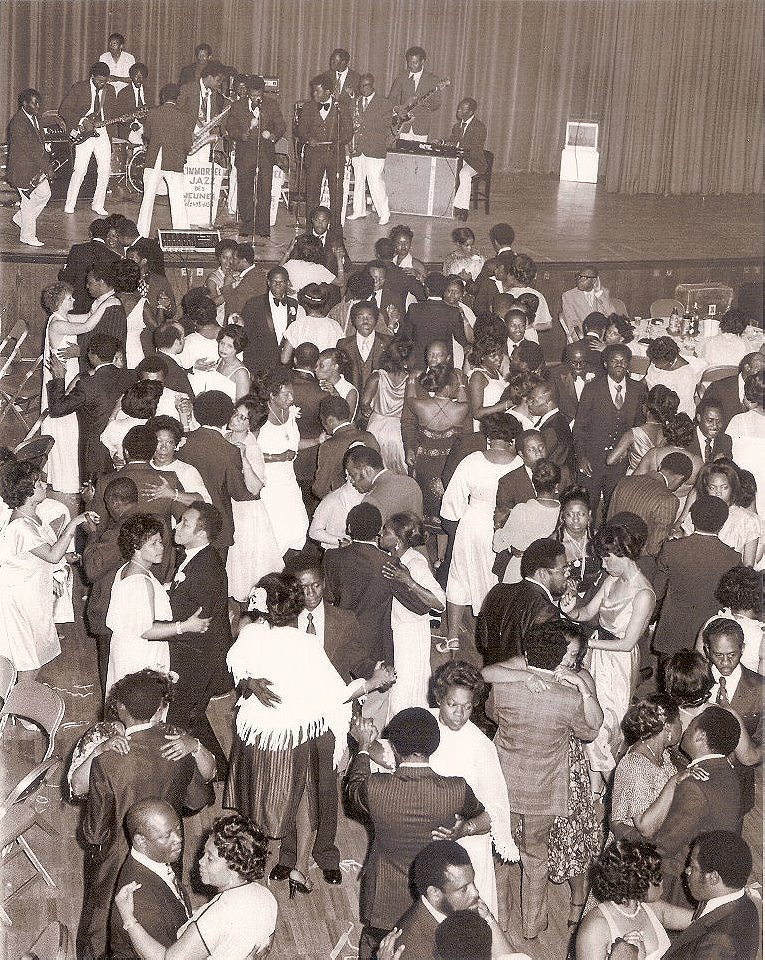

Haiti, like Cuba and Brazil, received a far greater number of enslaved Africans than the United States. Nago rhythms from what is today Nigeria and Benin, Kongo rhythms from Central Africa, and Petwo rhythms from the vodou traditions of Guinea, among many other influences, were revived in an age of black consciousness, driven by the Negritude and Noiriste philosophies of Afro-Caribbean intellectuals like Jamaica’s Marcus Garvey and Martinique’s Frantz Fanon and Aimé Césaire. The lasting result is a rich, layered terrine that spawned Haiti’s Cuban-inspired meringue; the dominant kompa direct of Nemours Jean Baptiste; the silky tenor sax-led cadence rampa pioneered by Webert Sicot; psychedelic mini jazz; and the dancefloor-filling vodou jazz compositions of the de-facto national orchestra, Super Jazz de Jeunes. At its peak, Haitian music was widely distributed, proliferating its unique blend of sound across the Francophone Caribbean and West Africa.

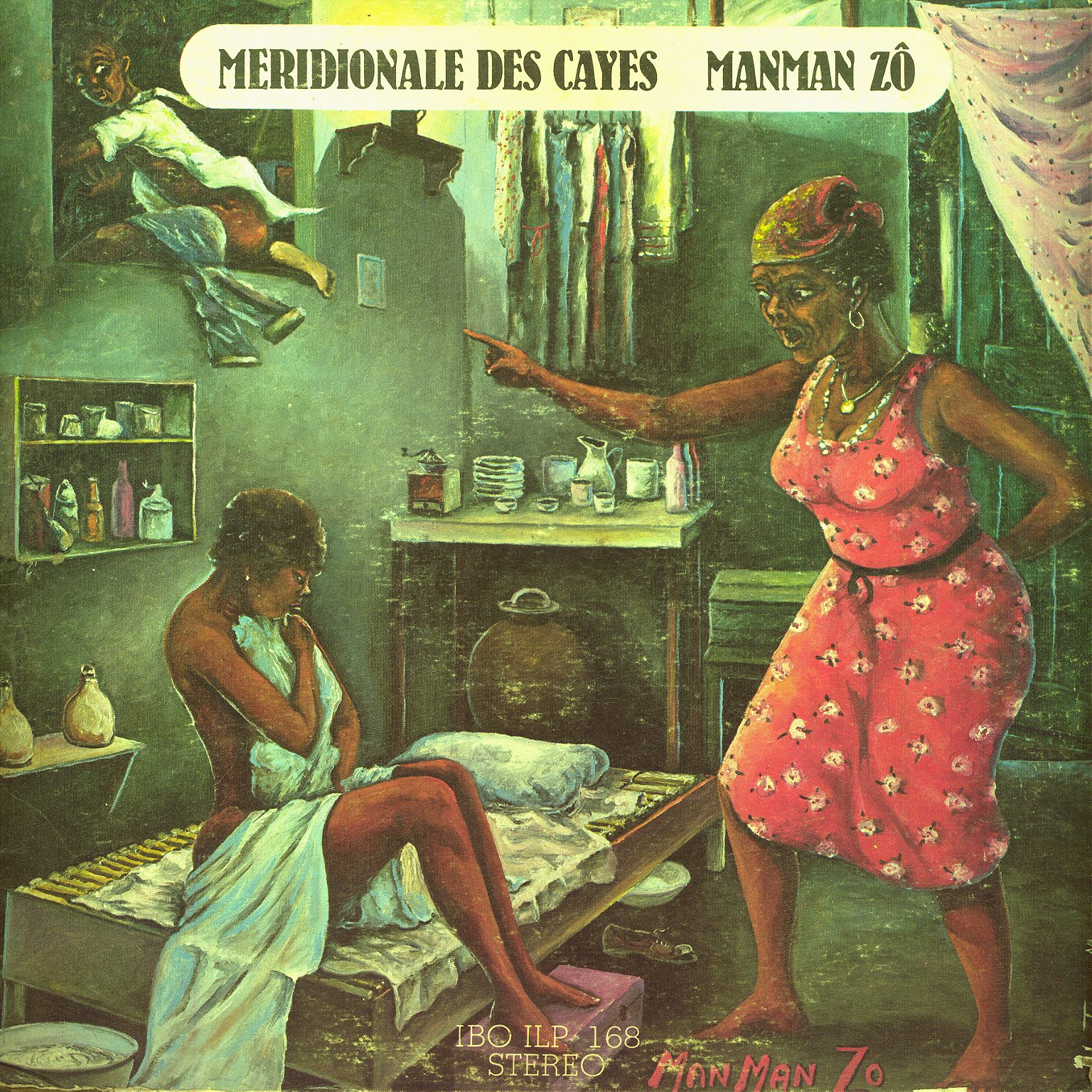

Recordings capturing this vibrant laboratory of colliding influences were produced and pressed in Haiti, the U.S., France, and elsewhere in the Caribbean. Huge catalogs from the heavyweight record labels of the time—IBO Records, Marc Records, and Mini Records—and the smaller, private presses have been largely forgotten in recent decades. Many people have tossed their collections or left them to warp in damp basements. A unique piece of Haitian history and culture was at risk of being lost. Most of the world had never heard these sounds, and I wanted to change that.

The roads of Port-au-Prince, Haiti’s capital, are unruly and unpaved, covered in dust and soot. Communal taxis, known as tap-taps, aggressively compete with oil and water tankers, NGO and aid agency vans, and armored vehicles carrying UN peacekeepers along the main roads. Police roadblocks bottleneck traffic in vital arteries of the city’s center.

But the streets are also home to a unique vibrancy. Roaming “rara” bands play folkloric rhythms with hypnotic horns and haunting percussion. Prim and proper uniformed youths flood the winding hillside roads around the capital to socialize over after-school snacks. The air is filled with smells of goat bouillon, pig feet ragout, and scotch bonnet peppers.

Radio stations were the first port of call in my search for buried recordings. The radio enjoys a special place in the Haitian imagination. It remains the most widely used conduit of information and entertainment for Haitians at home and in the diaspora. More than television, more than the Internet.

“The importance of radio among Haitian-Americans has its roots in Haiti, where the illiteracy rate is about 80 percent and most people cannot afford a television,” Raymond Cajuste, a radio show host, told the New York Times in 1993. “In Haiti, a peasant may not wear shoes, but he has a transistor radio.”

Radio’s prominence in Haitian life dates back to 1935, when Ricardo Widmaïer, a German immigrant, set up Radio HH3W, later named Radio D’Haiti, where some of the very first recordings took place. Ricardo’s son, Herby Widmaïer, established Radio Metropole in 1970. It played a key role in developing and advancing modern Haitian music.

Tucked away in a quieter corner of Port-au-Prince, Radio Metropole’s property is one of the best kept in the city. A garden, adorned with a range of flora, surrounds a stone lined walkway leading to the one-story building. I was given a tour by Herby Widmaïer’s son, Joel, who introduced me to an Haitian music insider: George Michelle, an aging man with a large figure and a commanding voice. Michelle was a close Widmaïer family confidant in the station’s early days.

In the backroom of their largest studio, now fitted with state-of-the-art radio technology, Michelle recalled the story of Radio Metropole and its impact on Haitian music culture. During the 1950s and early ‘60s, about a dozen AM radio stations were scattered around Port-au-Prince. With the import of new technology from Japan and Europe, Radio Metropole created the first FM radio station in the country. The sound quality increased, allowing for a host of radio programs, talk shows, and phone-in shows. Better technology led to greater influence, and Radio Metropole drove the popularity of Haitian music. Bands were frequently in the studio to play live. Les Difficiles de Pétionville, a seminal electric band from the upscale Port-au-Prince suburb, for example, earned the station’s highest ratings.

Metropole set the standard and inspired the growth of a broadcasting industry across the country. Radio stations like Radio Haiti Diffusion and Radio Caraibe, still standing today, began to spread the gospel of Latin music, especially Cuban music, which, in the same manner as West and Central Africa, had a huge impact on the development of Haiti’s musical identity. Alongside Cuban sounds, Mexican Ranchera, French music, and popular American jazz and soul made its way to Haiti’s airwaves. Michelle said that at one point Haiti was “overwhelmed” by Latin music. It won by default. But by the 60s, as more radio stations entered the market, Haitian music began to dominate.

At the time, radio stations still relied on magnetic tapes. Vinyl, Michelle said, was far too expensive and not readily available in Haiti. There were only three stores in Port-au-Prince at the time that sold actual LPs. Most of the records were pressed for the U.S. market and for Haitians in the diaspora, who could better afford them. Radio, as a result, played a huge role in the dissemination of popular Haitian music. This would explain the lack of vinyl culture in Haiti as oppose to other islands in the Caribbean, like Cuba and Jamaica, or Colombia’s Caribbean coast.

François “Papa Doc” Duvalier, Haiti’s brutal president from 1957 to 1971, used his secret police, the Tonton Macoute, against broadcasters deemed a political threat. Several radio stations closed, some by force, some voluntarily, and many radio owners and broadcast engineers left the country, Michelle told me. At Radio Jacmel, where I found the stash of rare vinyl, journalists were shot dead. Intellectuals who aired their views were also killed.

Journalists and other personalities at Radio Metropole were killed, jailed, or exiled. Music, however, was not forbidden under Duvalier. Some radio station, according to Michelle, were forced to play political music supportive of his rule, but, indeed, some of the most exceptional interpretations of Latin and Cuban music, as well as the deepest, darkest big-band vodou jazz cuts were recorded under Duvalier’s reign. Duvalier chose bands and organized carnival to promote his rule and enshrine his cult of personality. Haiti’s political elite, closely allied to Duvalier, became the biggest private audience for Nemours Jean Baptiste and Webert Sicot’s early bands. The rivalry and persistent competition between Jean Baptiste’s kompa direct style and Sicot’s cadence rampa vitalized the Haitian music scene, inspiring a generation of young musicians to follow their example.

It was here, at Radio Metropole, and at several other radio outlets, where I placed ads for every single piece of vinyl in the city, and dug through the radio’s archives.

Most people I met were bewildered by my quest. Not far from the presidential palace, I made my way to an old music shop selling only CDs. In response to my queries, a voice shouted from a group of men huddled outside: “Plaques? Plaques??”—as records are known in Haiti— “W ap chèche les plaques? No plaques!”

Roughly translated: You’re mad. Eventually the response to my incessant and persistent requests changed from laughter to annoyance. The devastating 2010 earthquake had destroyed many of the archives, and the pain of that loss was reflected in the reaction of radio operators, who rightly cherished these artifacts.

Many radio stations were also ruined during the earthquake. But the owners who lost nearly everything set up shop in makeshift studios on building rooftops, using the most basic of microphones, sound mixing boards, and transistors. One radio operator invited me to be a guest on a show dedicated to Haitian music of the ‘60s and ‘70s.

“You’re searching for the 33s (33 RPM), yes?” asked the radio operator in French. He was a rotund man with a round face, specks on his cheeks, and quiet grace in his deep voice.

“Yes, and 7-inch plaques.”

“You won’t find much in Haiti, there’s more in the U.S. and France and the other Caribbean islands. The earthquake crushed my radio’s archives and my personal collection.”

Word spread throughout certain circles in the city that I was in town looking for records. I continued to be greeted with disbelief and laughter at my mission. Radio station after radio station shooed me away. My phone remained silent despite a number of ads placed.

After two weeks, a call or two came in.

In downtown Port-au-Prince, I scoured old warehouses and garages, finding gems like Tabou Combo’s first LP with the track “Gislene,” a storming accordion-driven ‘60s Haitian dancefloor workout.

But I still wasn’t finding what the kind of huge stash I’d come here for. But then one day I got a phone call from a man who said he had collection of 3,000 records. It was exactly what I needed—a goldmine, albeit one covered in dust and insects.

I spent six hours with the man and his family sifting through and listening to the records. Here, in my dusty hands, was a rare piece of Haitian history, largely forgotten but still very much alive.

Vik Sohonie’s upcoming compilation, Tanbou Toujou Lou: Meringue, Kompa Kreyol, Vodou Jazz, and Electric Folklore from Haiti 1960-1981, will be released this spring on Ostinato Records. This piece is adapted from the liner notes.