Eighty years after the Spanish Civil War began, a small group of descendants is determined to identify the remains of thousands of victims buried in mass graves.

One afternoon in 2010, during the final session of an archaeology conference in Barcelona, Marc Antoni Malagarriga raised his hand to ask a question. In front of Malagarriga, a software developer in his early fifties, was a group of local experts who were explaining how two skeletons from one of Spain’s 2,000 mass graves were recently exhumed. After nearly eight decades under the Spanish soil, all that remained were two sets of pale-yellow bones. With no headstone to identify the grave’s occupants, and any clothing and belongings long since decomposed, when, Malagarriga wanted to know, would the panel take the DNA from the remains and identify the grave’s occupants? They would not, the experts replied. Without any local genetic records of possible candidates, DNA testing would be impossible. For now, the bodies would remain unnamed.

On Sunday, Spain marks the 80th anniversary of the start of the Spanish Civil War, a three-year-long conflict that began on July 17, 1936 after years of political tensions, and which would eventually claim 500,000 lives. Led by General Francisco Franco, nationalist forces attempted to overthrow the Second Republic’s democratically elected government. When the coup failed, the conflict erupted into a full-fledged civil war, pitting the right against the left and leaving helpless those caught in between.

After the war, soldiers on the victorious nationalist side who were killed in action and buried anonymously were exhumed and given new graves. Dead Republican fighters and non-combatant opponents of Franco were not afforded the same dignity. An estimated 150,000 bodies were unceremoniously heaped into pits that pockmarked the landscape.

The bodies have remained anonymous ever since. With virtually no genetic records of the victims and the relatives of the dead now in their seventies and eighties, or deceased themselves, collecting DNA to identify newly excavated bodies remains an urgent task. But a small team in the Catalonia region has dedicated itself to solving the mystery of Spain’s lost war dead.

Malagarriga’s uncle, Guillem, is somewhere among the unnamed. At the age of twenty, Guillem, a twin of Malagarriga’s father, refused to fight after receiving his draft card. The twins, along with their cousins, went into hiding for several months, until one night they paid to join a group of refugees that was heading to the Andorran border. The cousins and Guillem made it across the border. Malagarriga’s father, however, did not, and he was immediately imprisoned.

To ease the pressure on a family with three men missing, Guillem returned to Spain. Within days he was placed in prison for attempting to dodge the draft and was moved around different labor camps in the northeastern region of Catalonia. The last Malagarriga’s family heard from him was a year before the end of the war in a letter that informed them he was again being moved.

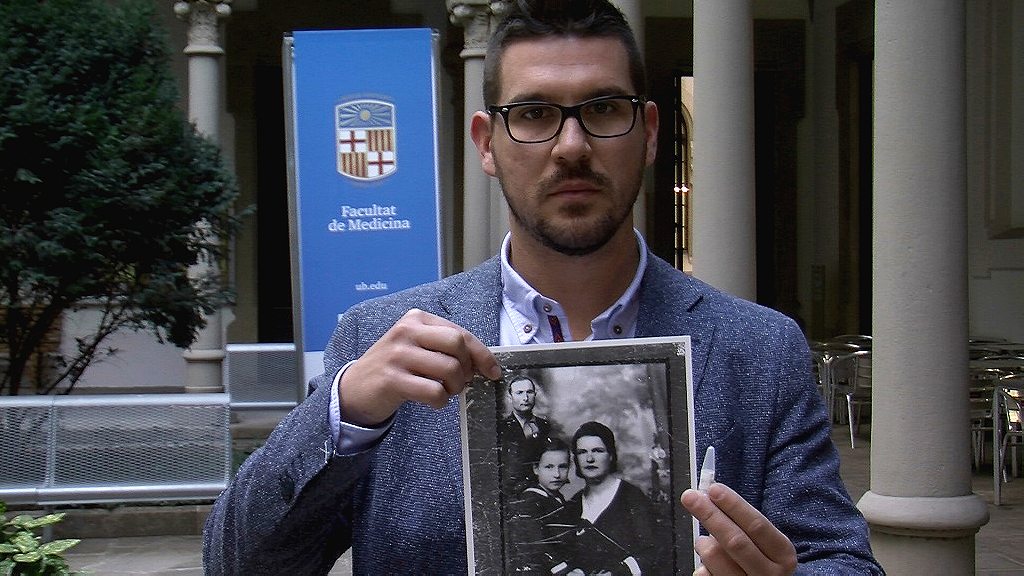

Malagarriga and his family have no place to mourn Guillem; no cemetery to visit, no headstone to clean. “When I was young at home,” Malagarriga says, “there was always a paperweight with a picture of a man inside wearing a suit. I remember when I was just a child and I first asked my mother, ‘Who is that man?’” That paperweight, amber-coloured, circular, made of glass and no bigger than a small coffee mug, is the family’s only token of remembrance for Guillem.

Although 80 years have passed since the war began and 40 since the end of Spain’s fascist dictatorship, only around 200 mass graves containing about 5,700 bodies have been exhumed. Spain’s “Pact of Forgetting,” established after Franco’s death in 1975, gave impunity to all those who had fought and subsequently worked for the dictator. Crucially, the pact enshrined a commitment that the 150,000 skeletons would remain buried.

In 2007, that commitment was legally challenged. Spain passed a historic law that not only condemned the Franco regime but also promised state support to the families searching for their missing relatives. For the thousands of families who had refused to forget their loved-ones, €25 million ($28 million) was made available to help their search.

The money lasted just four years. In 2011 the Popular Party, Spain’s right-wing party with historical ties to those who served the dictator, won a parliamentary majority. The country’s attempts to confront its past were put on hold. But funding for Franco’s giant Catholic memorial, an enormous mausoleum built by forced labor that houses the dictator’s body and lists the names of 40,000 dead nationalists buried in the surrounding valley, remained protected. Those buried in mass graves remained in the ground, unknown and unclaimed.

At the archaeology conference, when Malagarriga sat down after asking how such skeletons will be identified should more graves open, the broad-shouldered man wearing thick, dark-rimmed glasses in the next seat began to tell him about recent advances in DNA recognition. That week, Roger Heredia Jornet, a forensic scientist for the police, was on holiday. “I saw this conference was happening. I thought: I’m in Barcelona; I’m on my holidays. I’m going to go.”

We didn’t ever speak about the war at home

Jornet explained to Malagarriga how common it is for countries to store DNA to identify the war dead. In Argentina there is a DNA bank of 9,000 samples and how across the country there are over 50 centers where people can store their DNA for free. He noted how since 1999 in Bosnia and Herzegovina nearly 7,000 of the 8,000 victims of the Srebrenica massacre had been identified, along with another 10,000 people missing from the conflict in the Balkans where they have a DNA bank of over 27,000 samples. He also cited Rwanda, Guatemala, and Germany. He explained how DNA testing was not only used in historic cases, but as he knew from his daily investigative police analysis, more recent ones, too, like in 9/11 and Hurricane Katrina.

As the pair left the conference hall, they shared family histories. Like Malagarriga, one of Jornet’s relatives went to war and never returned. “I grew up never knowing about my great grandparents,” Jornet says. “We didn’t ever speak about the war at home and what had actually happened to my great-grandfather.” Jornet’s great grandfather, Jaume Guinau Estivill, along with the other men from his Catalan village, was sent to the battlefront at the Ebro River, one of the bloodiest battle spots of the war. Killed at 32 years old by a mortar bomb, Jaume’s body was never found.

They were shocked that the region in which their relatives were likely buried had no DNA bank at all. That afternoon, in 2010, they decided to set one up themselves.

Since then, Malagarriga and Jornet have collected 120 DNA samples from 90 Catalan families. The samples now sit in a large padlocked freezer in five-millimeter tubes in a laboratory in the Faculty of Medicine at the University of Barcelona. Even though Jornet spends his days in a white lab coat analyzing data from crime scenes, he isn’t actually the one who collects and stores the DNA. Instead, the pair enlisted another partner, Dr. Carme Barrot, a professor at the Universidad de Barcelona and director of the Laboratory of Forensic Genetics.

Barrot didn’t lose any family members in the war; her grandfather fought for the Republicans and survived. But when Malagarriga and Jornet contacted her, she agreed to meet them. “At first we offered them forensic support, but after I saw the families who came to give blood I saw that they had suffered so much in their lives. For me, after that, it was no longer just a project about DNA samples,” Barrot tells me in her university office.

Barrot brought a sense of urgency to the project. “I want the family member that has the most direct link to the body,” Barrot says. “A few times, I’ve made an appointment with the son of a person who disappeared during the war, but they’ve canceled… They tell me they aren’t feeling well, and then I call again to reschedule and they’ve died.” While Barrot can identify a skeleton without DNA from a direct descendent, if there is no living next of kin, she requires more than one sample of blood to increase the accuracy of the genetic reading.

In Catalonia, where the three are based, there have been just five exhumations of mass graves. According to Barrot, of those five, several of the bodies were unidentifiable once exhumed.

Even after 80 years in the ground, Barrot and her team can still identify bones. But the chances of a match don’t only depend on the quality of the DNA sample, but on the type of ground in which that body has spent the last eight decades. “If the body has lain in a dry atmosphere, we then have a perfect DNA profile. But if the body has lain in a wet or humid atmosphere, the DNA profile decreases.”

The Catalan government refused to share the data

Collecting blood samples from families that are searching for their missing relatives isn’t easy. Right now, the sample size is too small, and government inaction hasn’t made the project any easier.

The group expected resistance from Madrid, where the Spanish establishment has fought against attempts to confront the country’s fascist past. But they thought the Catalan regional government, which has long attempted to secede from Spain, would be more supportive. In 2011, 4,800 families registered as looking for missing relatives in Catalonia’s 350 mass graves with the Catalan government. Malagarriga and Jornet requested the contact details of all those on the list. The Catalan government refused to share the data.

“If the government informed all those families on the list, we could get a few thousand more samples,” Jornet says. Desperate to get the more reliable samples of DNA before it’s too late and a direct descendant passes away, Malagarriga and Jornet are working with political parties and lawyers to pressure the government. “Why aren’t they helping us? We don’t know. But we are going to continue to fight them,” Jornet added.

Over the last five years, Malagarriga and Jornet have held seminars in universities and events across the region, and they have given lectures explaining how the DNA bank works. In 2014 the pair made a crowdfunded documentary. The DNA bank’s most successful day, however, was when Jornet appeared on morning television. “Something really curious happened that day,” says Jornet. “When I explained the project and gave the telephone number of the show live on-air, so many people called in that the studio’s lines were blocked.”

As Spain marks the 80th anniversary of the start of the Spanish Civil War on Sunday, the country’s unresolved past has once again cropped up in the national consciousness. Jonathan Sherry, American Fulbright Research Fellow at the Universitat Autonoma de Barcelona, who is currently writing a book about political repression during the war, believes non-governmental projects like Malagarriga and Jonet’s are vital for modern Spain. “There is a public culture of silence in Spain about its bloody past,” Sherry says. “The right-wing political establishment have done everything possible to keep Spain’s secrets underground. The pair’s work is very important. It’s time for Spain to dig up the bones and bury the hatchet; not to deal with the past in some abstract way, but to know.”

For the past six years, Malagarriga and Jornet have been fighting against both a culture of denial in Spain and a political establishment committed to maintaining the secrecy and inhumanity of Spain’s post-Franco status quo.

While it is still common for elderly survivors of the war to refrain from discussing it, a division about how the country should confront its past continues to widen between its government and its citizens. Preparing for the day when all of Spain’s mass graves finally open, the need to collect the most reliable samples of DNA to help identify their remains is more urgent than ever.

“Spain is simply not a modern and democratic country because it isn’t confronting this problem,” Jornet says. “It’s fundamental that we remember what happened here, and we are going to continue to fight so one day we can know the truth about our past.”