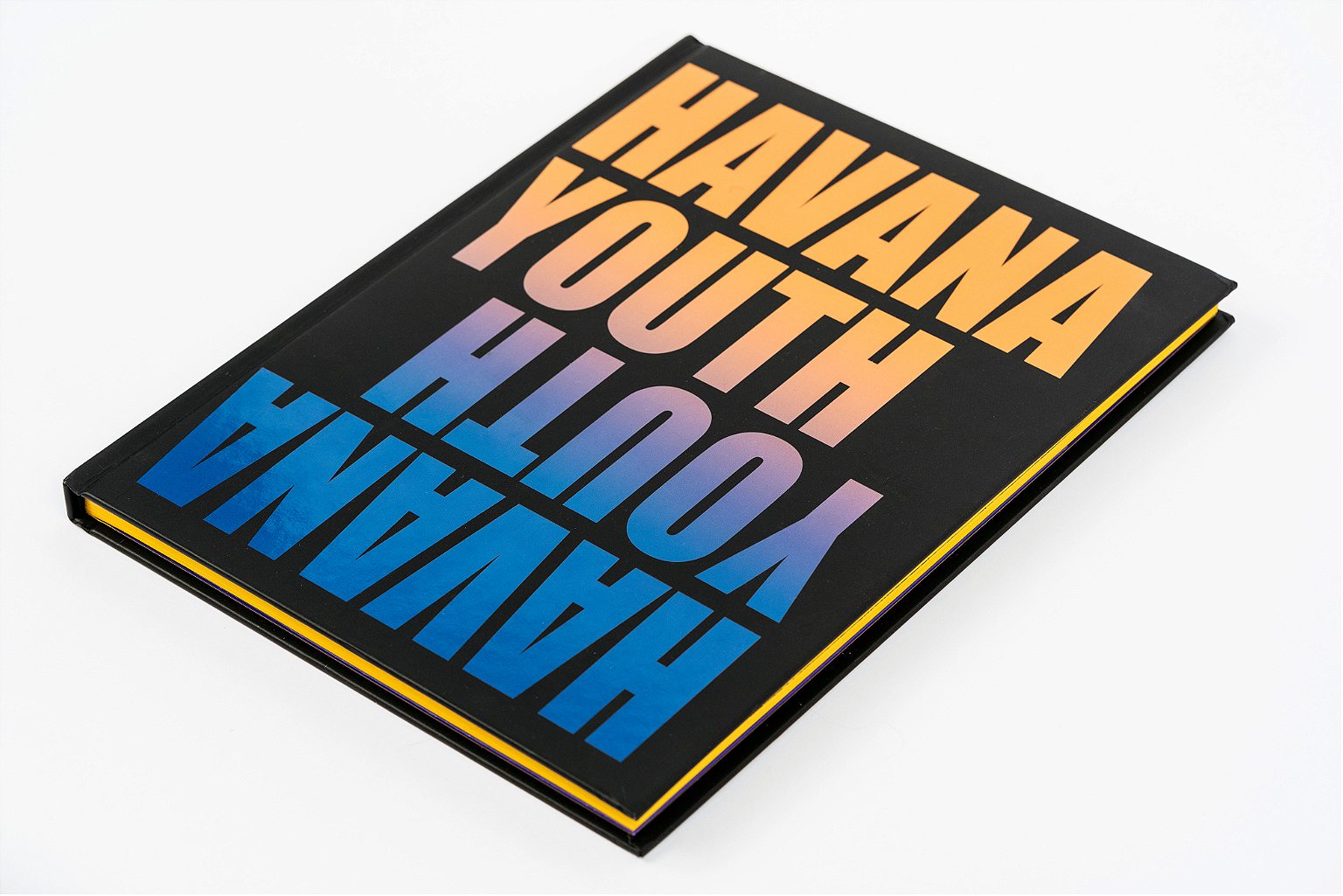

Photographer Greg Kahn’s new book explores youth culture in Cuba.

Greg Kahn was sitting at his fixer’s house in Cuba one night when he heard the thump of a bass beat echoing through the streets. He wandered outside, where he found a plaza with hundreds of kids dancing to electronic music. “It was current music that I had been listening to in the States,” Kahn said. “It just totally flipped that idea of everything that Cuba is.” Khan points to this moment as the foundation for his work over the next two years, and the subject of his new book “Havana Youth” (Yoffy Press).

“Havana Youth” is the DC-based freelancer’s first book, and its pages reveal the color and vibrancy of young Cuban society, brought to life by Khan’s meticulous attention to detail and intimate portraiture.

“This generation is changing that notion of what people think about Cuba,” Khan said. “That’s what I wanted to document.”

Roads & Kingdoms: How has the wider Cuban community reacted to this work?

Greg Kahn: I’ve received a lot of really positive feedback from people about the book, especially Cubans who escaped to the United States. People who are part of that other generation that might not have the connection back to Cuba—the people who left and have been waiting for the Castro regime to pass away and move on. They see this and think it is really interesting because they don’t have a connection to young people there anymore. They’re not able to see this part of it.

R&K: What do these young people want for their future and where do they see their country going?

GK: I think the most striking thing for me was that the narrative is typically that Cubans want to leave and come to the U.S. There are a lot that do, but I’m seeing a change in the mentality—that young people no longer look at leaving Cuba as the answer, but want to stay and make it the place they want. I think that’s a huge mind shift from previous generations.

There’s this guy, he’s a self-taught tailor, and breakdancer in one of these dance troupes. He’s got family members in Germany and Canada. He has every ability to leave Cuba legally and go live with them, but he doesn’t want to. He said “This is the place I want to be and I want to make Cuba the place that I dream about.”

Cubans realize that they live in a unique place and they are really embracing that. They’re not burdened by the past. They grew up when there were rolling blackouts, lack of food, and in a terrible economy. They have no illusions of the government providing. They’ve been establishing a counter-culture around it, and they’ve been able to do the things they still want to do outside of the government’s reach.

R&K: What types of changes have stuck out to you over the years of photographing in Cuba?

GK: I think the fashion scene has changed significantly. When I first started going, there was still very limited access to the kinds of clothing that they would see in the magazines. As one fashion blogger told me, “We used to look at these magazines and say, ‘Oh man. I wish I had something like that.’ Now they look at the magazine and say, “Okay. I’m going to get these things,” because there are now routes to get these things, whether it’s through Europe or somebody bringing it in from the States, but it’s no longer, “Oh there’s the outside world. I wish I could have these things.” It’s like, “No. No. No. It’ll take me longer. It’ll be a little bit more money, but I can have anything that I see here.” Now they’re developing a whole fashion scene that’s really exploding. I think it will, if it’s not already on the map in some places, be there very soon.

R&K: How is the internet effecting change?

GK: The internet’s a big deal everywhere. It’s a big deal here where we always want faster internet speed or whatever, but they’re basically just above dial-up in most places. Imagine being a musician trying to download music on dial-up. It’s nearly impossible. You can’t have an Apple Music account. You can’t have a Spotify account.

It would take these two DJs I met around 20 minutes to download one song. People in the U.S. get annoyed if it doesn’t start immediately on streaming. Because of this, people bring in hard drives from the outside loaded up with music. They always find ways around this kind of stuff.

There’s this thing called El Paquete (“the packet”), which is a hard drive or flash drive that gets passed around, and people pay a subscription fee for it. They have NFL games, movies, Telanovelas, music, and other cultural stuff. It lives in the gray area—not illegal, but not legal. It’s not legal in the sense that they’re putting all kinds of things on there, and they’re giving it to the people, but the government lets it slide because there’s no propaganda on there against the government. You balance this fine line. As long as you’re not upsetting the government, they’ll let it slide.

R&K: What about social media?

GK: Instagram is huge now, but it started off being Facebook. I would see Cubans hop on Facebook immediately. Say a dance group was touring Europe, all of a sudden my Facebook feed would be full of them at McDonalds or whatever because this is the first time they’ve ever had a Super Sized meal. But now, I think Instagram has really taken over too, which is just going to show you that they’re on the same kind of level as the rest of us. They’re not catching up anymore. They’re here.

They’re doing the same kind of stuff, but from a very different perspective. I’m seeing them repost a lot of artists or interesting accounts that they see. For example, this fashion blogger I follow is posting photos from shoots that he does all around Cuba. It is high-fashion photography. It is so wild to see it, because if you look at his account, you might think that he’s in Miami, but it is the way that he sees Cuba. The way that he interprets Cuba is not the way that most people see Cuba.

R&K: Are these parts of the culture clashing at all with others part of Cuban society?

GK: Cubans who work for the government make around 20 dollars a month, but these models are making way more. The dance troupes make way more. That’s why I ended up in a lot of the music and art spaces. That’s where people are making more money than typical jobs. That’s where I ended up going because that’s where there’s a lot of freedom. That’s where there’s a lot more ability to do the thing that you want to do, or buy a house or travel to Europe. If you’re with a dance troupe you might be able to travel to Europe for four months. Most other people don’t have that access. As an engineer in Cuba you don’t have the ability to go do that.

R&K: How do you view your role among the cliches of photography and Cuba?

GK: For a long time, Cuba was in a place where you had to sneak into the country to tell these stories. There was very little information coming out. Now with the connectivity that we have, things are opening up and we have the ability to see a larger section of Cuba.

It’s not to say that they don’t have crumbling buildings. It’s not to say that they don’t have a lot of old cars. But that’s not what I wanted to focus on, because I know people see that image. I’m not adding anything to that. If I take pictures of cars and old buildings, then I’m just following the same narrative. I want to do something that’s going to add to the conversation.

I want to have something that talked about this point in time for people there. I really honestly feel like we’re going to look back to this time period as when Cuba fundamentally changed forever. I think the Obama administration helped that happen by changing the relationship. I know we’ve taken ten steps back, but I think that we are going to look back and say this was a changing point in Cuba. I wanted something that kind of marked that time and showed that.

Everything is changing there, and it’s all happening kind of at once. You don’t see it because it’s not changing the buildings straight up. It’s not changing the old cars straight up. This visual that confronts you when you step off the plane is that it all looks the same, but as soon as you start to go inside people’s homes, as soon as you start to go out to some of the clubs, you see those changes very quickly and you see it reflected in the people there. So that’s what I wanted to stick with—that notion that, if I remove all those other things that keep Cuba feeling like it’s stuck in that same place, what does Cuba look like? I wanted to play with that idea of this rise in identity and individualism.

R&K: How do the people you talk with feel in the current political situation being played by the U.S. government?

GK: They’ve had a lot of terrible governments to deal with, so it’s hard to wow them. They say, “Yeah. Hold on a second. I’ve got 50 years of terrible governance to talk to you about.” They see the current administration and they say, “Yeah, that’s what governments are. They’re oppressive and they suck.”

They loved Obama. The way that he tried to change the relationship, they were all about it.

R&K: Have you thought about any continuation of this book?

GK: Yeah, I love the idea of going back and exploring more of that fashion angle. There’s a huge modeling industry that’s coming up, huge fashion designers, and people who manufacture their own stuff.

There are a lot of people who are trying to manufacture very boutique kinds of things, trying to design their own clothing, and have their own fashion shows with the stuff and the materials that they can import. Those are really interesting, because it speaks to that very fundamental idea of individuality. I want to see what that looks like in Cuba from a designer’s perspective and then go with the fashion blogger to see theirs.