Once regarded as a symbol of backwardness, Iceland’s historic turf-roofed homes are making a comeback.

Of the more than one million tourists visiting Iceland this year, many will get their first solid impression of the country from the 244-foot tower of Reykjavík’s Hallgrímskirkja. From atop the massive church, visitors get majestic views of Faxa Bay to the north, Mount Esja to the northwest, and the forested slope of Öskjuhlið to the south. For a tourist trap, it’s a decent primer for what this nation has to offer: bleak wastelands, soft idylls, and cozy homes. But in most of the uniform snapshots taken from the church’s tower, it’s the nation’s distinctive architecture, little LEGO-like buildings in neat rows of bright reds and blues, that dominates the frame.

Icelandic architecture looks quaint, yet it is almost all made of fine-grained concrete and corrugated metal sheets, materials associated today with the eyesores of urban-industrial decay. Durable and cheap, these materials are practical in weather-battered and geologically unstable Iceland. But the country has spun necessity and availability into something beautiful, even sanctified in the case of the nation’s tin tabernacles—tiny corrugated metal chapels. That’s the most visible ethos of Icelandic architecture: the glow of humanity shining out of rough materials.

But the sheet metal and gravel that has become synonymous with Iceland is, in truth, only a patina atop a much older architectural tradition. Until a century ago, and even into the 1940s, the nation’s skyline was dominated by squat, clustered turf houses. Yet despite turf’s vital role in Iceland’s history, you won’t see much of it today. Over a few brief generations, Icelanders have grown ashamed of and buried this architectural tradition, which has taken on the connotation of backwardness. Locals refer to turf houses as mud huts, a term bandied about whenever something (like the 2008 financial collapse) threatens progress, symbolizing a deep fear of returning to a Dark Age of global irrelevance and marginalization.

However a few Icelanders, chief amongst them Hannes Lárusson, are trying to break that mindset, encouraging their countrymen to honor and preserve the tradition before the last traces of it fade away. They’re not asking anyone to move back into turf homes. But they do hope that restoring respect for them will help Icelanders to deepen their understanding of their own history, the profound sense of individuality and adaptability in their culture, and how all of this stems from a carefully negotiated relationship with the land, from which we can all learn.

“This neglected, often despised, and misunderstood heritage is a key factor in the identity of Icelanders,” says Lárusson. “In the subconscious, all Icelanders live in turf houses… I see a lot of potential in a ‘revival’ of this old heritage in reinterpretations and integrations of many of its unique aspects in contemporary, sustainable, green architecture.”

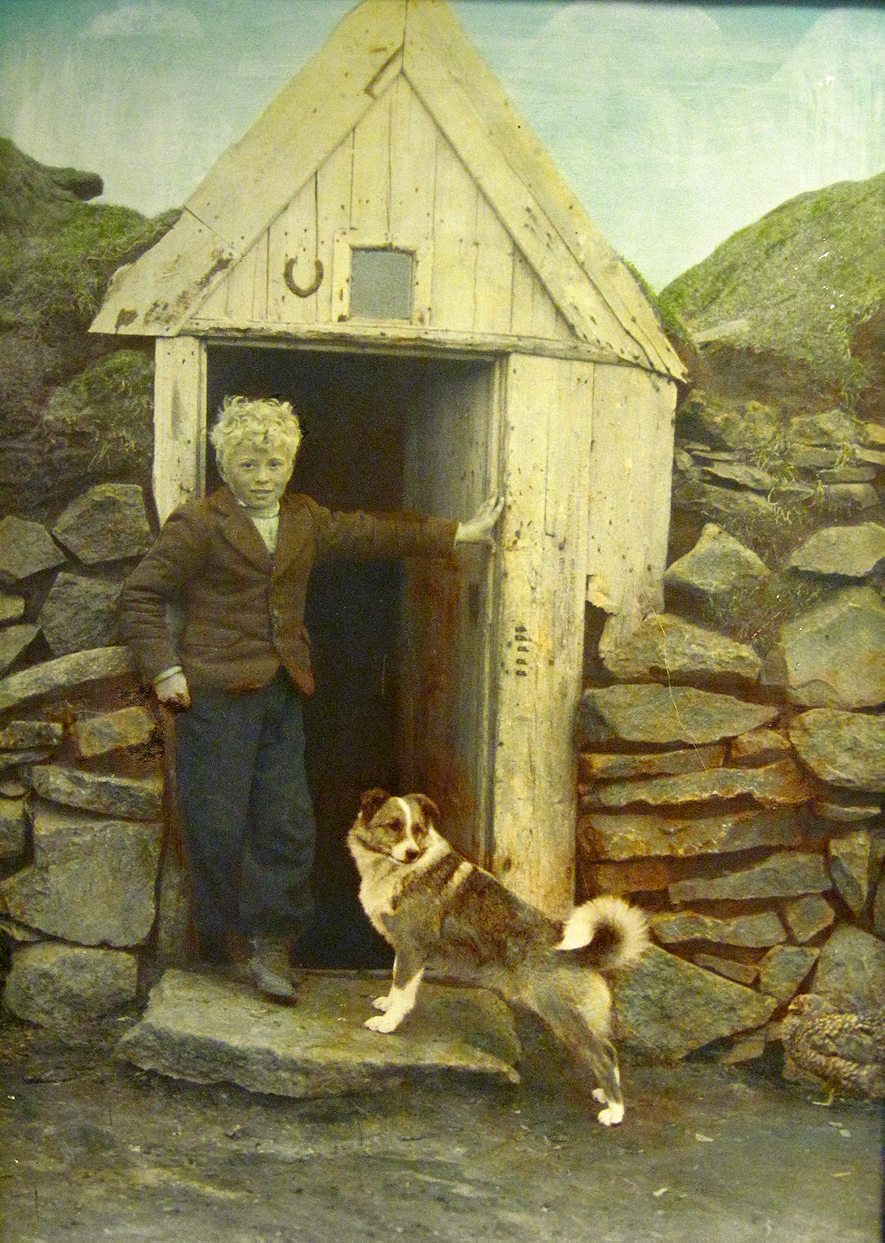

Lárusson leads the charge for turf farm preservation and recognition from a base of operations just 40 miles from the Hallgrímskirkja. That’s where his passion for turf architecture developed, as he spent his first nine years living at Austur-Meðalholt, his family’s earthen estate. Only in early middle age, he’s one of the last young Icelanders with childhood memories rooted in sod.

Ever since he inherited Austur-Meðalholt in the mid 1990s (by which point it was arguably the last commoner’s turf farm in the nation) he has made it his mission to preserve the farm, drawing together a waning collective of specialized craftsmen to help him learn how to constantly restore the sturdy, efficient, yet temperamental structure. But he’s not just preserving it for himself—he’s turned it into the Íslenski Bærinn, a museum dedicated to helping his countrymen find the value in the dirt.

Lárusson’s been applauded for his work. But he’s also been derided. A 2005 article in the local Farmer’s Journal accused him of mocking his forbearers’ suffering by painting their dirty hovels as pleasant and intelligent designs. But Lárusson is convinced that as long as he keeps the tradition alive, others will come around to his point of view.

Iceland’s turf houses are part of a common northern European architectural tradition dating back to the Iron Age. In Celtic and Nordic lands, locals insulated themselves from polar conditions using earth, especially where resources were scarce. But nowhere in the region did turf architecture reach a greater scope or sophistication than in Iceland.

When Nordic and Celtic settlers arrived in Iceland (c. 874 A.D.), they built longhouses using the wood from the island’s vast, low birch forests, supplemented with a bit of turf. But soon enough they’d totally deforested the island, and found themselves so isolated that they had to rely on driftwood. A shipwreck was a cause for celebration.

But turf was plentiful. Icelanders developed specialized tools and crafting skills, turning turf houses from basic dugouts, which replaced longhouses in the 14th century, to (by the 18th century) complexes of wood-framed and gabled specialized structures—one-room kitchens, stables, and living quarters all in a row. Styles varied drastically between regions. Even individual farms were idiosyncratic. But all required near-perpetual upkeep and reconstruction, and provided the same warmth in a central badstofa—the communal living and bedroom.

Although some families had so little fuel that they had to put their main living room over a barn to warm themselves with their livestock, for the most part the turf houses were comfortable, not the damp, disease-ridden pits many imagine. Unlike in other parts of the world where turf architecture was reserved for the literally dirt poor, almost every Icelander for the better part of a millennium lived in turf. Iceland’s elite just made larger estates, decked out with luxurious wood paneling and fixtures in every room.

Lárusson cannot stress turf’s livability enough. He doesn’t just want people to reevaluate their views on whether turf houses could be comfortable; he wants them to understand that they’re missing a vital understanding of comfort by not having lived in a turf house: “Unless they are familiar with the living main room of a traditional farmhouse,” Lárusson wrote in an article on turf houses, “No one can understand completely the concept of warmth.”

In the 18th century new forces came to bear on Icelandic architecture. Danish merchants and officials (who’d administered Iceland since the 14th century) kicked off a wave of urbanization, importing more timber to build their own grand houses in the style of their homeland. Then in the 1860s British traders introduced corrugated sheet metal. It was durable and strong, and the British were willing to trade it for sheep, which the local merchants had in spades. Then in the 1920s concrete followed. And with these new materials came new architectural styles, riffing not on turf and Icelandic structural traditions, but on Danish, Norwegian, and even Swiss models.

Around the same time, Iceland was becoming increasingly independent (achieving full sovereignty under the Danish crown in 1918) and increased its trade with other nations, recognizing through these interactions that it wasn’t nearly as developed as its neighbors. The quest to modernize Iceland became a huge driver in the growing nationalist movement, but this impulse did not feed itself on local culture.

“Icelanders looked abroad for models of modern life,” writes Sigurjon Baldur Hafsteinsson, a professor and national cultural expert at the University of Iceland, in a 2011 article on historical cultural perceptions of turf houses in Iceland. “[There was a] perceived need for Icelandic culture to change and display additional proofs of a higher level of civilization in its architecture.”

Hafsteinsson has collected a treasure trove of newspaper clippings from the late 19th and early 20th centuries that show the logic that led to the rapid villainization of the turf house. In 1878, a commentator in the newspaper Ísafold called turf houses a “national vice, a ruinous inveteracy and senseless adherence to ancient customs.” By the turn of the century physicians were labeling them as miasmic death traps, robbing Icelandic men of industrious potential. Some towns banned residents from building with turf. By the 1920s, Hafsteinsson says, turf houses were completely out of vogue.

Simultaneously in the early 20th century, people fled rural farms for better opportunities in Reykjavík, (which today is home to 200,000 of Iceland’s 323,000 citizens) and other coastal towns. They left thousands of turf houses behind to rot back into the earth. These ruins and un-housed gave national planners a good excuse for aggressive new anti-turf policies.

“It became a national project to eradicate these traces of where the turf houses were,” says Hafsteinsson, “and renew Iceland by renewing their old [lands] with new materials and styles.”

Around 1900s, Iceland had about 6,000 bær – or farms – and a total of up to 100,000 individual turf structures. By the 1930s, though, official figures put that count at 3,665 bær. But there was only so far this modernizing impulse could go. Iceland was still a comparatively poor nation built on an uncompetitive fishing industry—until the Blessed War.

Britain panic-invaded Iceland

During World War II, after the fall of neutral Denmark in 1940, Britain panic-invaded Iceland, pre-empting any Nazi plans to use the island as a chokehold over the North Sea. Iceland’s Prime Minister, Hermann Jónasson, was able to work out a rough deal with the Brits: tacit cooperation, the ability to feign neutrality, and compensation for damages done. In 1941, when the UK handed Iceland over to the US, Jónasson managed to strike a better deal, trading his cooperation for cash and development aid.

Icelanders weren’t always happy to see 30,000 American boots on the ground, as many still felt occupied and worried that these brash outsiders would corrode their culture, corrupt their women. The occupation took a human toll too. At least 200 Icelanders died war-related deaths.

But even the staunchest opponents to the American presence couldn’t deny that they drastically altered the nation’s infrastructure, and provided a massive cash injection. By the summer of 1942, military engineers had arrived, laying down roads, constructing Keflavík International Airport (which still serves the country today) and paying thousands of locals to support them.

The country grew by about nine percent every year, according to an estimate by Professor Guðmundur Jónsson, a University of Iceland historian. As the Americans left in 1946, they gave the newly independent government rights to all the improvements, and to all the corrugated iron barracks around the island, many of which were stripped for parts or transported whole to serve as barns. In 1948, the U.S. even gave $43 million from the Marshall Plan to Iceland.

Flush with resources, Iceland ran roughshod over the remainder of its turf houses. By the turn of the millennium, only 60 to 80 remained, according to Lárusson.

Even before the worst of the decline began, the National Museum of Iceland had taken an interest in preserving turf architecture, managing to land turf structures on a list of national protected structures in the 1940s. Today, about 32 turf structures have been preserved by the museum or other institutions.

But for Lárusson, this preservation is anemic. Few of these structures are fully intact. Most of them are elite buildings or churches, nothing like the popular Icelandic experience with which he hopes his countrymen can connect. Plus, he points out, the National Museum treats turf more like a curiosity to be considered from afar. There’s no challenge to reevaluate, no effort to extract or highlight the heritage and lessons in these structures. It’s a pretense of preservation that allows people to disregard turf—to think nothing about tearing down one of the last bær in 2011 or pejoratively throwing around the phrase mud huts.

Lárusson believes his museum can encourage people to reevaluate turf houses by inviting visitors inside Austur-Meðalholt and presenting them with an image of a common person’s lived experience in the sod. Sitting in a badstofa, feeling the wood and wool of a communal bench bed, listening to the stories his family used to read at night—he seems to hope that this can trigger an openness in visitors. “When it comes to vernacular architecture,” he writes in a recent article on the revival of interest in turf houses, “exploring with your body is the only way to [truly] enter the house.”

By allowing people to interact with turf, he hopes he can undo years of propaganda denigrating it, allowing people to re-embrace a part of their cultural heritage. By asking people to keep the skills of turf architecture alive and preserve what sites remain, he hopes that modern Icelanders will be able to learn and adapt the lessons of harmony with nature that their ancestors fought long and hard to learn and institutionalize on the island.

“In the process of producing a turf-built house,” Lárusson wrote in a 2006 article, “man and nature make a new covenant. The regular renewal of the turf-built farm is part of its character, experience, and intellectual [and environmental] depth.”

In the past, it may have been difficult for Lárusson to draw attention to his project—and even harder for him to convince people to get their hands dirty with him. But his Íslenski Bærinn may have come into being at just the right moment.

The economic chaos of recent years has forced many Icelanders to reevaluate the trajectory of modern societies. A general turn towards authenticity and away from mass production makes tradition and sustainability powerful buzzwords these days, especially for young people.

“More Icelanders are looking at this heritage with a sense of pride rather than shame,” Lárusson says. “Young people are also often more open-minded and see the important parallel between the turf house, vernacular architecture on a global scale, and contemporary sustainable or green architecture.”

The Íslenski Bærinn does seem to be taking off. Local school children are visiting the museum, running their hands over a piece of their nation’s history and learning something other than the mud hut narrative. If children soak up Lárusson’s love of turf houses, and tourists demand more of this authentic, sustainable experience, then eventually the nation will have to confront its historic rejection of turf houses.

Lárusson does see more willingness to embrace turf than in the past. His project of respect and restoration has a real chance. But if he fails to perpetuate turf traditions and respect in a new generation, then the craft may well die within our lifetimes. With it would go a huge chunk of Iceland’s history, buried in shame and moldering back into wet sod.