For a generation of Koreans, hard, coarse, oily cornbread—courtesy of the U.S. government—is a nostalgic treat.

My brother and I have just finished eating chili and corn muffins at a popular barbeque joint in our hometown in Maryland. We think the muffin tastes pretty good, so we bring some home for our mother. “It’s pretty good,” she initially remarks, but proceeds to make a face of distaste after we tell her we paid the ludicrous price of 85 cents for the small piece of food.

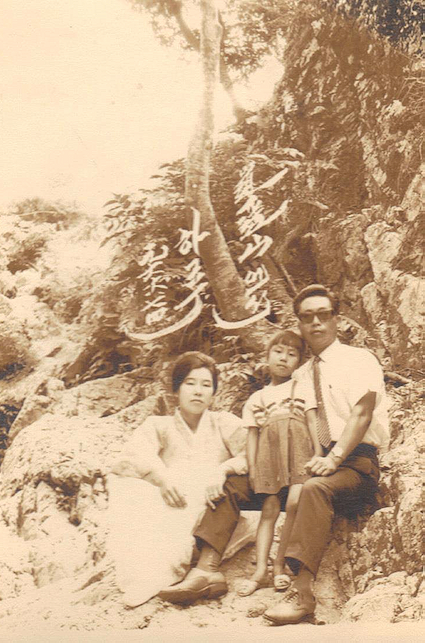

Our family conversations for the past few months have revolved around the cornbread my mother had as a child. My mother, whose Korean name is Myong, has expressed her strong desire to taste this bread again. “That is the one thing I wish I can eat again before I die,” she has told me.

Today, when many people think of cornbread, they think of southern barbeque. For my mother, however, the first thing that comes to mind is the snack she received in school while growing up in South Korea during the 1960s.

After she has a couple more bites of the muffin, we ask her if it tastes like the one she remembers from nearly 50 years ago. She says it is sweeter and softer than the one she received as a 9-year-old schoolgirl in Dongducheon, a small South Korean city north of Seoul and southeast of the 38th parallel that houses several U.S. military bases.

Myong lived in Dongducheon from 1960 to 1968, as the nation recovered from damage inflicted during the Korean War. To assist with food relief, the Cooperative for American Remittance to Everywhere (CARE) provided cornmeal to primary schools starting in 1961, according to Kyoung-Hee Park, who detailed U.S. food assistance to Korea during the years after 1953 for her dissertation at Leiden University.

Park writes that the cornmeal was initially prepared as gruel, but that production was difficult and expensive to maintain because some schools could neither support the cost of labor nor provide sufficient cooking resources to prepare the food. The solution lay in mass production. Korea began to mass-produce wheat bread in Busan in 1963, and it was through this process that the cornmeal, along with powdered milk and a small amount of sugar, was made into a piece of cornbread that was distributed to almost every student in the country.

“If you were being a good student, you would get an extra piece of bread,” my mother recalls. “They used it as an award for good behavior. So I guess that bread was kind of special. It made you feel good when you got two.”

Su Nam Kim, director of American Center Korea at the U.S. Embassy in Seoul, emailed me her own memories of her school’s cornbread distribution, which have a more political bent:

It was also memorable because the food, cornbread, came from America, a friend country who loved to help Koreans like me. At that time the only two countries I was aware of was Japan and North Korea, both were known as our enemy … and it was a pleasant shock to me with the fact that our country has a friend! Cornbread symbolized to me as ‘friendship’ and as symbol of good neighbor.

Kim’s view of the relationship between the U.S. and South Korea during this time is entirely positive, but as is often the case, that’s not the whole story. While the cornbread was initially part of a relief effort, the donation of wheat flour to Korea in 1966 by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) was motivated by potential political and economic benefits for the U.S. In his dissertation, Park argues that the U.S. and its food relief programs had more strategic aims than just relief. Though this wheat flour created a white bread that was softer than the cornbread—which was nicknamed “stone bread” for its hard texture—the donation also marked the introduction of American foods to Koreans with the intent of establishing South Korea as a future export market.

Cornbread was the first Western-style bread my mother ever ate

In 1954, the U.S. created Public Law (P.L.) 480, a program initially designed to decrease the surplus of U.S. agricultural goods—particularly grain—by exporting them to foreign markets. Originally, the exports served as food relief, but it then shifted into a food loaning system after 1961, Park says. A USDA Foreign Agricultural Economic Report records that South Korea received $1.7 billion worth of agricultural goods under P.L. 480 from 1955 to1976. By the 1980s, the USDA reports, “South Korea was a top commercial market for U.S. agricultural products.”

Nevertheless, among my mother and her friends, as well as Kim, the white bread is not as popular of a memory as the cornbread. The white bread was an improvement, but they stick to the memories of the rough and gritty cornbread, as it was something entirely new. Though my mother did eat steamed dough, which was wrapped around a ball of meat to create a dumpling, she believes the cornbread was the first Western-style bread she ever ate. Its seemingly unappetizing trait of being hard and rough in texture is what made the bread so unique.

“Maybe I was just hungry, but I remember tasting that bread and it was very good,” my mother recalls. “It was something new to us, I guess, that we never had before. It was oily outside, and the rough texture of the bread, somehow I liked it.” The oil could have been either cottonseed or soy, which were both part of the regular export of surplus agricultural products from the U.S. to Korea under P.L. 480.

Today, the search for this elusive cornbread is ubiquitous among a certain generation of South Koreans. Popular New York-based Korean food blogger Maangchi put in much time to recreate the cornbread she fondly remembers from her childhood. She writes on her blog, “I had almost forgotten all about [the cornbread] until one of my website readers asked me if I knew how to make it. She was Korean, but living in the U.S. for a long time, and really wanted to taste that bread again. Suddenly, I did, too! I remembered the smell of the bread, the slightly gritty texture, the strong corn flavor, everything. I also remembered the excitement of me and my classmates when the bread came, and how happy we were.”

A California-based food blogger, who goes by the name of Seoulism, also attempted to create a recipe for Korean-style cornbread and was particularly focused on replicating its texture. He writes on his page, “This bread is very similar to American cornbread but the edges are harder and the outside has almost a crunch like texture.” My mother provides a similar recollection, saying the texture was comparable to a corner piece of a brownie.

Over Thanksgiving break, I had my brother follow Seoulism’s recipe to see if this cornbread was similar to the one my mother had as a child. I, however, came across the ratios of cornmeal to powdered milk to sugar in the original list of ingredients—provided by Park—and tried to come up with my own recipe, which failed miserably.

The product of Seoulism’s recipe was similar in taste, but off in texture. According to my mother, Seoulism’s recipe had the right strong corn flavor and was not too sweet. The texture, however, was too dry, as the one she ate in Korea was oilier.

The bread was tasty and edible, though, and was a nice afternoon snack for our family. On the other hand, the product that resulted from my reverse engineering went into the trash. In Park’s research, he found that the original ingredients included 62 grams of cornmeal, 40 grams of powdered milk, and one gram of sugar per piece. When I mixed these ingredients, though, the batter was extremely watery from the milk. After multiple attempts, I still could not get a consistency that even looked remotely correct.

I was probably missing some eggs, baking temperature, and perhaps baking soda. However, I hope that upon seeing Park’s ingredient ratios, someone with more baking prowess than myself will come closer to recreating the original recipe.

Though the recipe for the cornbread from the 1960s is still being sought, Korean-style cornbread can be found in Korean bakeries across the U.S., such as Shilla Bakery, a well-known chain in the Maryland and Virginia area. After my mom rekindled a friend’s memories about the cornbread they ate as a child, one of them went out and bought her a bread sold by Shilla called “Corn Crown.” The bread is geared towards Korean taste, so it is less sweet than American cornbread. However, according to my mom, the bread was not “rough enough” and did not have enough of a corn flavor. The one from the bakery tasted more like a cake. The search continues.

“Each generation has a certain food they remember,” my mother says. “When you share certain things during a difficult time [in] your life or social setting, that certain thing you share is special because of that. People still remember, my generation, that taste.”

As I have gotten older, I’ve realized that my mother as her own person—her unique life experiences, her thoughts, her story—has been overlooked, perhaps in the face of fulfilling traditional duties as a mother, sister, daughter, and former wife to a late husband. I also think the expression of her personality and uniqueness has been hindered by the fact that, like many immigrants, her main focus for many years was working hard to help provide for her family. Although inevitable, I find this lack of expression to be a shame, since the immigrant life is arguably one of the most dynamic.

When my mother began talking about this cornbread, I wanted my mother to be recognized for her unique life, and not just how well she performed her obligations. It was only after doing more research that I found this unique memory about a very particular type of cornbread to be prevalent among her generation. As my mother said, this piece of food tied together a generation of school children in Korea, and continues to bring them together almost half a century later as adults scattered around the U.S. as immigrants.

The Korean immigrants who came over to the U.S. during the end of the 20th century were not looking to fulfill great materialistic ambitions, such as having a nice car and home, nor were they looking to fulfill personal ambitions. Rather, this generation of Korean immigrants came to the U.S. looking for a sense of security, contentment, and establishment, which is expressed through the Korean term anjung. They were okay with not having much, as long as what they did have was enough to support their family.

When I found out that the U.S. strategically used school lunch programs to transform South Korea into a future export market, I felt resentful. My mother, as well as the others who received this bread, did not know that the U.S. was conditioning them to become accustomed to an American diet so that Koreans could become customers to the U.S. market.

Yet, there is something poetic and rather funny about the fact that this generation remembers the cornbread with such fondness, not the white bread. To most people today, the cornbread would probably be met with distaste. The grittiness of cornmeal is something one tries to get rid of. To my mother and her generation, however, the rough and gritty cornbread they received was more than enough.