Bordering war-torn Crimea, the world’s oldest steppe reserve—home to zebras, buffaloes, and wildebeests—fights for survival.

ASKANIA-NOVA, Ukraine—

Viktor Gavrilenko charges across the Ukrainian steppe at nearly 60 miles an hour. His rickety, dark green Lada bounces wildly over the parched grass and kicks up clouds of dust as we overtake terrified herds of buffaloes, zebras, wildebeests, and antelopes. About two dozen cranes pass somewhere above us in a perfect wedge formation, dark shades against the pale blue sky, like a bomber squadron going to war.

When we finally spot a band of Przewalski’s horses, Gavrilenko steps on the brake abruptly, as if pulling on imaginary reins. With the engine still running, he jumps out of the car and glues an enormous pair of binoculars to his face.

“Good morning, ladies,” he calls out to the mares in the distance, squat brown figures with bristling black manes. “Such beauty, such beauty!”

Fifty-nine years old, with tousled salt-and-pepper hair, small lively eyes, and a hooked nose peering over a bushy mustache like a bird from its nest, Gavrilenko is the director of Askania-Nova, the oldest steppe reserve in the world. Located in southern Ukraine, near the border with Crimea, it sprawls over 33,000 hectares (81,000 acres) and includes one of the last remaining patches of virgin steppe, as well as herds of free-roaming mammals brought in from as far as Africa, Central Asia, and the Americas. It is Ukraine’s most famous and popular nature reserve, or zapovednik—a sort of Ukrainian Serengeti.

The Eurasian steppe is an enormous semiarid grass belt that stretches from northern China and Mongolia, through Russia, all the way to Ukraine and into Hungary. For well over two millennia, the region has served as the highway of human civilizations, the wide-open road that history marches on. Like the American prairie, the steppe is a place of myth, an infinite landscape of rolling grass. “You go on and on and there is no way to tell where it begins and where it ends,” wrote Anton Chekhov at the close of the 19th century in one of my favorite stories, “The Steppe.”

The western edge of the steppe, in Ukraine, has been the quintessential frontier of Europe and one of its most contested regions. It was once known as dikoe pole, “the wild field,” and it took the Russian Empire until the end of the 18th century to subdue it and bring under imperial control its various nomadic and seminomadic groups. The very name Ukraine means “borderland.” Now, history seems to be repeating itself. The steppe has become a frontier once again.

When I visit Askania-Nova at the end of September, the iconic fescue and feather grasses, dotted by red tulips and purple irises, have long gone to seed under the harsh summer sun. But the immensity of the steppe, stretching out in all directions, is still dizzying. There is certain grandeur in monotony.

“We need rain, rain, rain. The whole steppe really changes with the rain,” says Gavrilenko, as if ashamed that I could not witness the steppe’s full splendor. He tells me that for all his years at the reserve, he has never experienced such dry weather. Climate change is real here. It the 1990s the average rainfall was 450 millimeters (17.7 inches), and this year it has been just 190 mm (7.4 inches). “In the spring, if you listen carefully, you can hear the grass grow: puk, puk, puk,” he said. “You should come back here again.”

If Peter the Great opened a window onto Europe, Putin is now closing it

I don’t know if I would be able to return, as it was not easy to reach Askania-Nova. With the violent conflict in eastern Ukraine still raging, and Crimea recently annexed by Russia, I had to pass through a string of military checkpoints, where gruff camouflaged men were digging trenches and wielding Kalashnikovs, armored vehicles and tanks waiting at the side. “Putler, stop!” one hand-drawn road sign read, referring to what many locals see as Putin’s Hitler-esque ambitions in Ukraine. Air defense batteries and radars were stationed near Askania-Nova, ready to respond to a Russian invasion from Crimea. Everyone and everything was gearing up for war.

“Even in my nightmares I couldn’t imagine that Russia would attack Ukraine,” Gavrilenko tells me when we go back to his office in the administrative wing of Askania-Nova, a spacious room full of books, a jumble of papers, and framed desk photos of a red-backed shrike and a Eurasian hobby. “If Peter the Great opened a window onto Europe, Putin is now closing it.”

Gavrilenko makes a pause and takes out a cotton handkerchief to wipe his rheumy right eye, which suffers from some kind of ophthalmic condition. He would be the last person to shed a tear, yet his gesture seems somehow symbolic.

“The worst is that the plan to start a quarrel in one’s own house seems to have worked,” he said. “As a biologist I’m familiar with this intra-species conflict, which is the nastiest one in the natural world. We are an aggressive species, very aggressive, like the chimpanzee that kills its own. We destroy everything in our path.”

Much of Gavrilenko’s professional career has been dedicated to preventing man’s destructive tendencies. An heir of Don Cossacks, the famous frontiersmen of the steppe, he grew up on a farm without electricity and became a passionate devotee of nature at an early age. He went on to study zoology and nature protection, and quickly established himself as one of the Soviet Union’s leading environmentalists. In recognition of his achievements, he was given the management of Askania-Nova in 1990, a job he has excelled in and one that has made him a minor celebrity in his homeland. If you work in nature conservation in Ukraine or Russia, you certainly know Viktor Gavrilenko and his near-fanatic commitment to his work.

“We’ve been given this historical heritage, and it’d be criminal to abandon it,” he says about his job. “We are obliged to preserve it for the next generation, it is our duty. If we can’t take care of the present, we’ll be denied our future.”

The history of Askania-Nova is long and variegated. (“Like a zebra skin—one bright stripe followed by a dark one,” Gavrilenko says.) It was founded as a private nature reserve in the late 19th century by a landowner of enormous wealth and ambition, Friedrich Falz-Fein, an heir of German settlers in the region.

The Falz-Fein family ran one of the biggest sheep-breeding operations in Russia, in addition to owning a shipping company, a private port on the Black Sea, vast orchards, and a canning factory (whose logo was a gold fish riding a bicycle).

A gentleman of progressive ideas and something of an amateur conservationist, Falz-Fein decided to fence off part of the virgin steppe on his estate in order to protect the original flora from the plow and the sheep, which were quickly and irreversibly changing the landscape of southern Ukraine. But his ambition went further: He wanted to introduce wild animal species, local but also foreign, that thrive in steppelike environments. In a sense, Falz-Fein was an early, if idiosyncratic, proponent of what conservation biologists may today call “rewilding.”

Soon enough Askania-Nova housed herds of critically endangered saiga antelopes (once abundant on the Eurasian steppe), buffaloes, zebras, camels, ostriches, wildebeests, and even kangaroos, many living in semi-wild conditions. In 1899, Falz-Fein sponsored an expedition to Mongolia, which procured Przewalski’s horses, the last truly wild horse—an effort that decades later would prove instrumental for saving that species from extinction. He also created a zoo and an enormous dendrological park, irrigated through deep artesian springs in the middle of the arid landscape, which earned Askania-Nova the nickname “oasis on the steppes.” When Czar Nicholas II visited in 1914, he was so impressed he made Falz-Fein nobility. “It’s quite amazing,” the czar wrote in a letter to his mother. “It looks like a picture from the Bible, as if all the animals have come out of Noah’s Ark.”

But tragedy was waiting in the wings. Located at the gates of Crimea, in the direct line of some of the most intensive fighting of the Russian Civil War, Askania-Nova was soon devastated, and Falz-Fein was forced to flee to Germany. When the Bolsheviks took over the reserve, they slaughtered many of the animals for food, and used artillery against the herds of wild horses and antelopes, mistaking them for enemy cavalry, remembered Falz-Fein’s brother Vladimir in his memoir. In a fit of cruelty and boredom, one the soldiers started to decapitate rare breeds of geese with his saber. “Off with the bourgeoisie heads!” he shouted as he brought down the blade repeatedly.

Though it suffered much damage and was later nationalized by the Soviet state, Askania-Nova did survive, and some important scientific work on ecology continued in the relatively liberal 1920s. It was the rise of Stalin and his plans for “the great transformation of nature,” envisioning the absolute subjugation of natural environments to industrialization and large-scale agriculture, that turned much of the reserve into a livestock breeding operation. Junk science experiments with animal hybridization (crossbreeding zebras with horses or buffaloes with domestic cows), aimed at creating species and increasing output, became one of the central tasks. There were even attempts to commercialize the milking of eland antelopes.

Only in the 1980s, as the Soviet regime was falling apart, did real work to restore Askania-Nova’s conservation mission commence. The place became part of the UNESCO network of biosphere reserves and, under Gavrilenko’s tenure, it finally managed to separate from what was called until then the Ukrainian Institute of Animal Husbandry of the Steppe Regions. In 2008, its popularity growing and boasting well over 100,000 visitors each year, Askania-Nova was voted one of the Seven Natural Wonders of Ukraine, and went on to represent the country in an international initiative called New7Wonders of Nature. Even though it did not win, the recognition was sufficient honor.

Few tourists have dared to come out here recently. When your country is at war, the economy is collapsing, and fear stifles the air like a thick blanket, going on a nature trip in the steppe is not exactly a priority. As far as I can tell, I am the only guest at Kanna (“The Eland”), a Soviet-era apartment block converted into a hotel, its lobby decorated with antlers and paintings of deer, just like a hunting lodge.

“Business is really bad now,” says the hotel’s receptionist with a sigh. “The events have scared everyone away.”

The streets of the town of Askania-Nova (population 3,500) are eerily empty, and only the locals go about their usual business. If it were not for the steppe reserve, the zoo, and the dendrological park, which together employ about 300 people, the place would look like any small Ukrainian town: charming single-story houses, some painted the traditional blue of the region, intermixed here and there with hideous dirty-white apartment blocks. Long clotheslines with colorful laundry stretch between communal spaces. A few older people sit on wooden benches, while young kids play at war with sticks and branches.

In a house on the edge of town lives Nikolai Lobanov, a 90-year-old veteran of the Battle of Stalingrad, who came to Askania-Nova in 1952 and eventually became one of the leading authorities on Przewalski’s horse breeding and conservation. Although he has some difficulty enunciating words, his memory is lucid and he still recalls most of the details of his life: the Ukrainian famine of the 1930s, when he hunted sparrows and ground squirrels in the steppe; his miraculous survival during World War II; the night classes studying zoology; his meeting at Askania-Nova with Joy Adamson, the famous naturalist and author who was later murdered in Kenya; his friendship with Gerald Durrell, the late English conservationist.

Lobanov is also an accomplished artist, and his house is full of his paintings of gorgeous zebras, antelopes, and flamingoes drawn in the primitive style of Henri Rousseau. A true child of the steppes, he has a love for wildlife that seems boundless. But when I mention the current war in Ukraine, he suddenly turns angry.

“The fascist junta in Kiev is to blame for everything. They started the war first,” he nearly shouts. “Russians are our dear brothers, we fought against the Nazis together, defended the Soviet Union. This land has seen too much blood and it doesn’t need more.”

Then, as if trying to tame his thoughts, he asks me, “Did you see the cranes? They are beautiful.”

On my last day in Askania-Nova, I decide to take Lobanov’s advice and go see the cranes. They congregate here in the early fall, tens of thousands of common cranes (Grus grus) resting and feeding on their annual migratory journey from Scandinavia and west Siberia to the Middle East and east Africa. With slate-gray plumage and long legs, a stately black neck with a streak of white extending behind the eyes, and a red crown on top, these birds are the royalty of the steppe.

In the pre-dawn hours of the morning, while the constellations still stud the clear night sky, I meet Alexandr Mezinov, an ornithologist and the head of the zoo section at Askania-Nova. Together with his team, we’ll be heading to a low-lying, marshy section of the steppe called Bolshoi chapelski pod, or the Great Heron Depression, to count the cranes. Keeping track of numbers helps determine the health of a particular population and its migratory patterns.

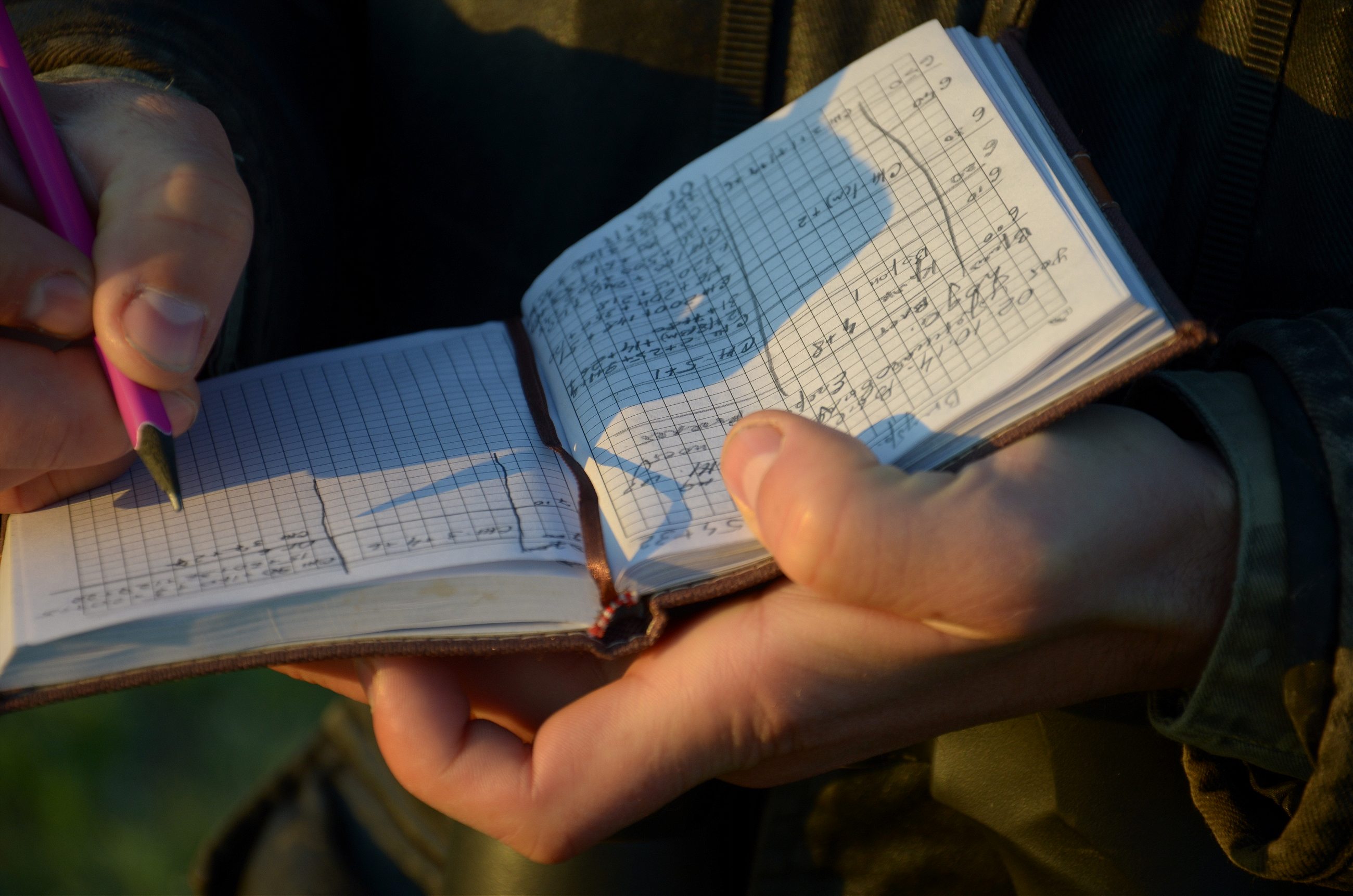

On Lenin Street, right in front of the zoo, we all climb into a gray UAZ-452, a Soviet off-road minivan popularly known as bukhanka, or “bread loaf,” and head toward the steppe. Everyone but me is dressed in some kind of military fatigues and carries a pair of binoculars, a notepad, and a pen. While we are driving on the bumpy road, Mezinov relates a story about a group of fishermen from a nearby village who recently went out fishing in a boat near the coast of Crimea. As soon as they got drunk, they started shouting, “Putin is a dick,” but the Russian border guards thought it was a Ukrainian invasion and nearly opened fire. All the ornithologists in the van start laughing.

We stop at different points along the way, equally spaced, and one by one people get off to man their observation posts: The whole perimeter of the steppe has to be covered so the counting is as accurate as possible. Finally, Mezinov and I leave the van.

It is freezing outside and still dark, but pale patches of pink and orange already light up the rim of the horizon. Somewhere in the distance we can hear the broken calls of the cranes, like experimental jazz trumpets, as they gather to fly out and begin their daily foraging. While we are waiting, we rub our hands together and stamp our feet to keep warm.

“You have to be out in nature to see the subtle changes,” Mezinov tells me, staring at the horizon. “A lot of scientists just sit in a chair in a city office and pretend they can understand nature. They read books and receive grants but know nothing. Here we fix the facts through observation.”

Mezinov tells me how certain bird populations have been plummeting in the past few years, as wetlands and estuaries disappear, and poaching and pollution increase. In 2004, he says, they counted 14,500 nesting pairs of great bustards, but in 2012 there were only 4,500. In the early 1990s, there were some 35,000 pairs of wild gray geese in Ukraine, but those have gone down substantially as well. Migratory patterns have changed too: The warming climate has convinced a number of bird species, including some cranes, to winter in Askania-Nova, rather than fly south.

As the disk of the sun slowly emerges, I can make out small black silhouettes grazing in the distance: herds of American buffalo and Przewalski’s horses. A short sprinkling of rain a few days ago has swiftly awoken the grass from its dreamless slumber. Now, in the morning light, its copper sheen gradually turns emerald, bejeweled by delicate drops of dew.

The crane calls slowly rise in volume and frequency, like music tracks overlaid on top of each other, until everything turns into unceasing, deafening background noise. One by one by one, the birds take to the air: We see formations of 10, then 20, 50, 100. Mezinov’s trained eye needs just a glance to determine the numbers, before he quickly writes down the information in his notepad.

“Cranes like ships, sailing up in the sky,” I remember a line from an old Soviet movie about World War II, The Cranes Are Flying. Cranes like ships, sailing up in the sky. When the last armadas finally pass over us, Mezinov and I stare after them for a long time and keep silent. Wherever they are coming from, wherever they are going, we hope their journey is safe, far from our weapons of war.

Travel for this story was funded by the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting.