Sydney’s most debauched neighborhood is the epicenter of an Australia-wide problem of unprovoked violence.

SYDNEY, Australia—

In the news footage, taken at the scene of the crime, the perpetrator Shaun McNeil seems stunned but lucid. His shirt is open; not ripped, but purposefully unbuttoned to show off his pectoral muscles and a tattoo that reads, “Trust is Everything.” Blood drips from his nose.

“It was one punch,” he says over and over again. “It was one hit, that’s it.”

The police and media here sometimes refer to acts like this one, which occurred on New Year’s Eve, 2013, as a “coward punch,” with the goal of dissuading drunken young men prone to violently jumping unsuspecting passers-by. Before that they were called “one-punch attacks.” Even earlier they were known as “king hits.”

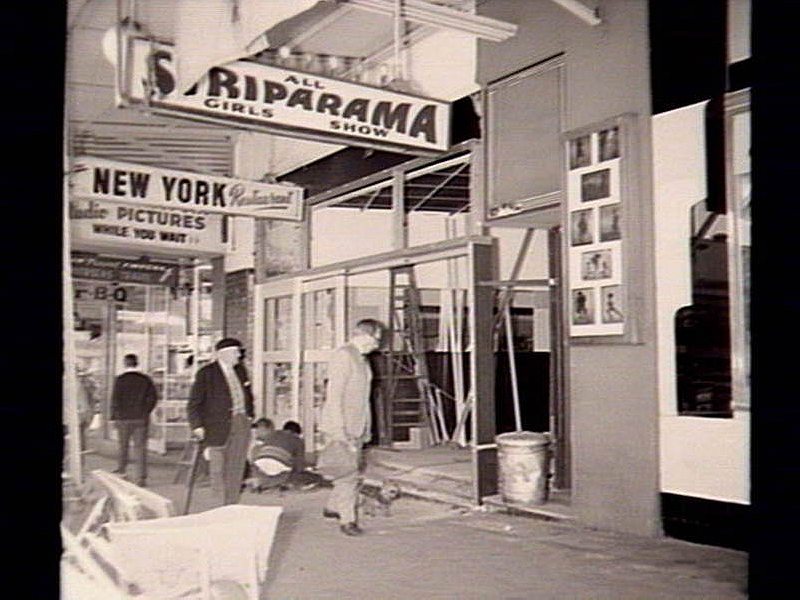

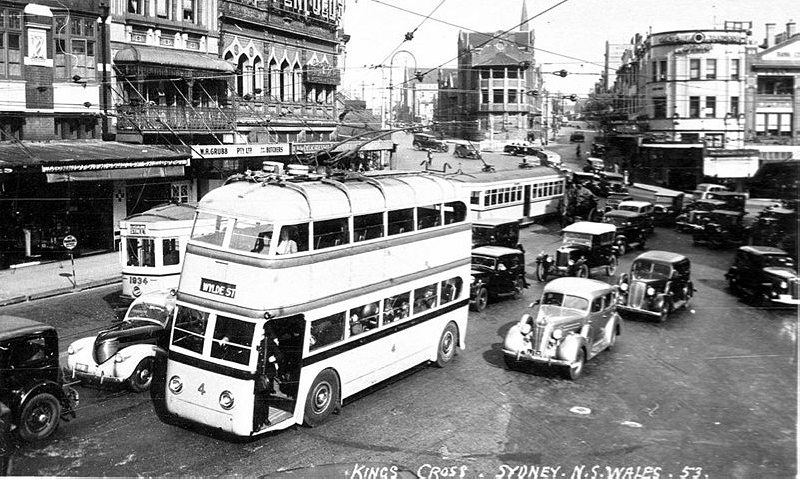

Whatever your preferred nomenclature, the place to go in Sydney for an unannounced fist to the face is Kings Cross. Just up the road from the naval base and host to innumerable tacky bars, dingy strip clubs, and a healthy drug trade, the Cross has long been associated with both organized crime and the tourist industry.

Recently, however, it’s these random punches that have attracted the most attention. A friend of mine, stopping to light someone’s cigarette outside a pub, was rewarded with a split lip. A similar incident in 2012 resulted in the death of Thomas Kelly, who was attacked while talking on the phone. Doctors at the local hospital have come to expect a serious head injury of this kind about once a fortnight. The problem of unprovoked attacks isn’t confined to the Cross: nationwide between 2000 and 2013, a shocking 91 Australians were killed in one-punch attacks of this variety.

The man McNeil assaulted that evening, Christie, suffered brain damage while falling and was taken off life support later that month. He had interrupted McNeil attacking three minors who had offered to sell him drugs.

On June 11 of this year, McNeil was cleared of murder but found guilty of the lesser charge of manslaughter and various assault charges. He’ll serve a mandatory seven-and-a-half years before being eligible for parole. Christie, who was 18 when he died, has become a symbol of the grisly outcome of drinking and violence in Kings Cross.

The Cross is bounded by sticks and stones. At one end of the main drag, set against the Sydney skyline, is Ken Unsworth’s outdoor sculpture Stones Against the Sky (jokingly referred to here as “Poo on Stilts”), and at the other end is the dandelion shaped El Alamein Fountain, which commemorates the battle of the same name in Egypt during World War II.

In the quarter mile between are two dozen bars and half a dozen strip clubs, and a few brothels. There are many more drinking establishments on the nearby streets. The Cross is historically Sydney’s seediest district, featuring cathouse razor gangs, BDSM dungeon murders, disappearing journalists, and worse. Today the neighborhood is defined by drugs, sex, music, gambling, and cheap, rundown backpacker hostels.

It’s for precisely those reasons that a large and rowdy crowd of young people are drawn here every Saturday night. Before the introduction of the new laws, some nights as many as 20,000 would revelers stagger along Darlinghurst Road. Vomit and urine lie in puddles on the pavement outside the bars, and violence is common.

The deaths of Daniel Christie and others were the last straw for the state government. Barry O’Farrell, the premier of the state of New South Wales, introduced hardline “one-punch laws” including mandatory minimum sentences for crimes, declaring “The new measures are tough and I make no apologies for that.” Soon afterwards, he fled politics, harried by the scandal of undeclared donations from property developers. In his attempt to transform Kings Cross from a red-light district to a somewhat respectable nightlife entertainment center, lockout laws were instituted in February 2014. Among other restrictions, no one can enter a Kings Cross pub after 1:30 a.m., and last drinks are now called before 3 a.m.

Assaults plummeted. So did business. Foot traffic is down 84 percent, compared to 2012 figures and dozens of bars, hostels, and hotels have closed doors—a third of the area’s licensed venues so far. With patronage falling faster than crime, violence has actually risen on a per-capita basis. But neither the slatternly romance of the area, nor the boisterous boozy posturing, look likely to survive in the future. Whether a middle-class restaurant district will spring up in their wake is yet to be seen.

The harshest of the new laws only apply to Kings Cross and the city center. This leaves other tourist hotspots like Bondi and the Star, Sydney’s only casino, well-attended. It’s too early to make a definitive assessment, but the casino at least has reported a doubling of assaults.

More notable has been the changing crime rates in the student suburb of Newtown. Traditionally, there’s plenty of class warfare here, but very little violence—landmarks include a mural of Martin Luther King, next to an Indigenous Australian flag. It’s also been one of Australia’s most LGBTQ-friendly areas.

But the recent beating of a transgender woman in a pub is evidence that something’s changed. The latest official figures show an 80 percent jump in assaults on licensed premises, and a massive 169 percent increase in alcohol-related crime, although other reports suggest that the laws have resulted in a statewide fall in violence.

It’s been suggested that revelers, seeking to avoid the lockout laws in King’s Cross, have shifted here, bringing violence with them. There’s a vague sense that “the ‘vibe’ in Newtown is changing,” as Jenny Leong, local state member of Parliament, put it to a community meeting on July 6, 2015. And that vibe isn’t necessarily reflected in stats and figures. Insults and shoving are difficult to quantify and report on in the way that traumatic brain injury is.

Local pub owners are divided, and most are reluctant to speak with the media after a string of negative press, including a “hatchet job… run by dickheads” at a Sydney tabloid, as one told me, referring to coverage of a recent punch-up that put the blame on security staff. One exasperated bar worker in Newtown told me that she and others in the industry don’t often bother reporting more minor incidents to police, asking, “What would that achieve?”

Some bars had urinals installed under the countertops

In response to the perceived growth in troublemaking, a Newtown industry group has jointly decided to trial self-imposed regulations based on the Kings Cross lockout laws. The land of hipster bicycles, fair trade vintage shops, and WAR IS OVER graffiti is so fraught by violence that calling last drinks early seems to be the only way forward.

This is far from the first time Sydney has tried to confront its drinking problem. Similar regulation of closing times throughout the 20th century led to the Australian phenomenon known as the “six o‘clock swill.” With only an hour to drink after work, men were so reluctant to leave the serving area that some bars reportedly had urinals installed under the countertops.

Looking further back in time, Australia’s only successful armed coup—the 1808 Rum Rebellion, overthrowing the ill-fated William Bligh of Bounty fame—was in part catalyzed by arguments over the use of hard liquor as currency. It may seem a long way from colonial insurgency to punch-ups outside strip clubs, but maybe the glorification of boozy violence and the failure of authority to control it has always been a part of Sydney’s mean streets. A Federal Inquiry led by Senator David Leyonhjelm, to be held later this year, will determine whether the lockout laws are an appropriate way to address the issue.

Shaun McNeil has a pair of tattoos across his forearms. “CHRISTIE,” reads one; “IN GOD’S ARMS” the other. It’s a memoriam to a former partner or relative, not the man he killed, but the irony doesn’t distinguish. While walking through Newtown last week, a man spat on my face and slurred a homophobic insult. I wiped the phlegm off, and squared off with him, thought about those tattoos, and thought about throwing a punch.

Fortunately, neither of us were willing to take it that far.