In the foothills of Mount Kinabalu, Southeast Asia’s tallest mountain, an artist collective fights punk’s global homogenization by mixing local political issues with DIY art.

I’m standing inside a sun-scorched country house contemplating images of a rural revolution while cattle graze outside the window. The pictures are etched on A3-sized posters hanging from the walls: dozens of black figures printed on multicolored paper. I lock onto a portrait of a Kadazan-Dusun woman in a conical paddy hat. She looks ahead proudly with pursed lips; long, beaded earrings hanging from her ears. Her hands are placed before her chest to emphasize an intricate, hand-woven beaded necklace. Over the tip of her hat, instead of the iconic “punk’s not dead,” the artist has penned “Bead’s Not Dead” in curling letters.

“Here in Sabah, the tribal handicraft industry is still very much alive,” says Rizo Leong, 31, anticipating my question. We’re in his home studio in the mountain village of Ranau, located in Malaysian Sabah, the northernmost region of Borneo (the world’s third largest island, shared by Malaysia, Brunei, and Indonesia). “Because of the trinkets sold by Malaysia’s Tourism Department, the local artisanal trade risks to die off,” he explains. “I want people to know that local peasants are still producing art, and that they need to sell them in order to stay alive.”

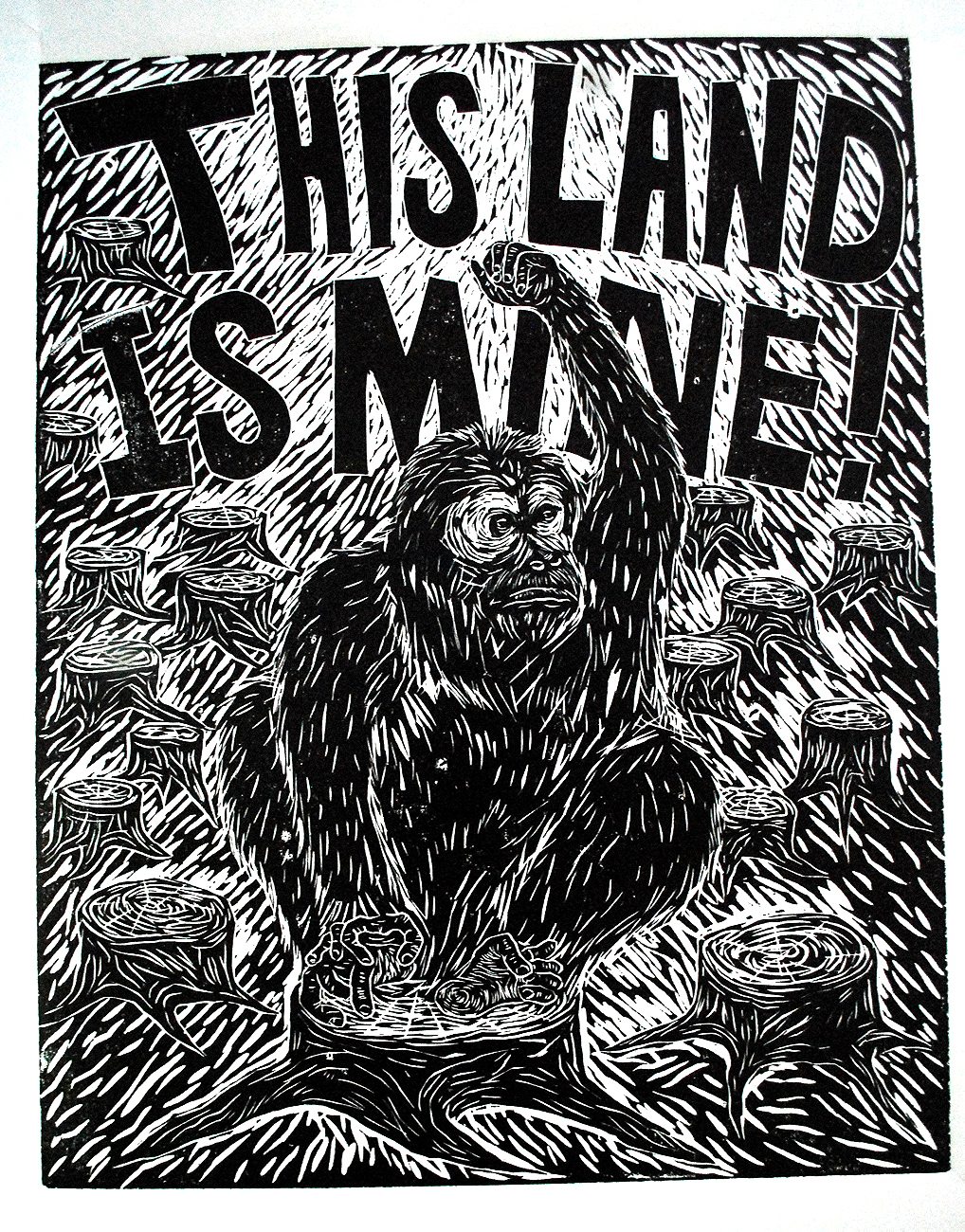

Punk is much more than just music: from anarcho-punk collectives to feminist riot grrrls, since the early 1980s the “punk” label has encompassed a grassroots network of independent record labels, fanzines, art collectives, bands, and enthusiasts who reject mainstream capitalist and consumerist society. The specialty of Sabah’s rural punks is the creation of politically conscious art that examines the plight of local tribal peoples and endangered animal species.

Leong’s a native Kadazan-Dusun, the umbrella term given to a collection of more than forty sub-ethnic groups constituting the orang asli (original peoples) of Sabah, historically a crucible of cultures and peoples from Indonesia, the Philippines, and more recently, Malaysia. Leong was born and raised in Ranau, a one-horse town at the foothills of Mount Kinabalu, Southeast Asia’s highest peak and a popular tourist attraction. With long, black hair reaching down to his back and an artsy goatee, this energetic man looks more like a member of Lynyrd Skynyrd than a master of DIY punk rock art.

“I’m not an artist and don’t think of myself as a punk rocker,” Leong says shyly as a flock of white clouds slides above the silhouette of Ranau’s low, sun-soaked slopes. “I’m just an orang kampong, a country boy.” Kampong boy or not, the work that Leong and his art collective Pangrok Sulap have produced over the last couple of years has made waves. (The group’s name is a cheeky combination of the local pronunciation of “punk rock” and the Kadazan-Dusun word for a tribal hut.) Ranau’s collective received the attention of Malaysia’s national newspaper, The Star, and secured exhibitions nationwide; it also now has a far-flung representative in Tokyo.

As far as influences and style go, Pangrok Sulap doesn’t look to America or Europe, instead drawing from closer to home: right across the southern border that splits Malaysia and Indonesian Kalimantan at the neckline of Borneo, and then down to Java. “Sure, I have grown up listening to American bands such as the Dead Kennedys and Minor Threat, but what they sing about is very much different from Sabah’s situation,” explains Leong. “We decided to drop the music and concentrate on using art to show our dissent towards the specific problems that afflict our land. There’s a very narrow scope in talking about anarchy and fucking the police, when the reality here is completely different from the West.”

Pangrok Sulap’s art is largely made using woodcut printmaking. Leong and friends work with pencil, pen, and scalpel, chiselling wood panels to create the intricate stamps they use on different types of fabric and paper. Once a design has been sketched and carved into a wood panel, Ranau’s art punks smear it with black newspaper ink and place it on the surface they want to imprint. It’s not an easy job, especially since they must carve a negative image of their designs.

“We take inspiration from punk’s DIY concepts, but we know we can do much more than just that. DIY is a boring concept, because it’s just an individual choice. We, to the contrary, prefer to do it together,” Leong says as he places one of the carved wood panels over a white cloth, then covers it with newspaper. Freddy and Bam (the English names preferred by two other members of Pangrok Sulap) walk over to the panel to help press the ink evenly into the fabric.

In the spirit of do it together, they invite me to join them. We all stomp carefully over the edges of the stamp while the sounds of Indonesian punk rock blast out of a tiny stereo placed at the farthest side of Leong’s huge studio. This space doubles as a home for him and his wife his wife, Memet, as well as a haven for travelling punks and eccentrics from all walks of life. It was this hospitality that created Pangrok Sulap in the first place.

Leong first encountered punk rock thanks to friends from nearby Kota Kinabalu, Sabah’s major city center. “We used to play in bands and organize shows here in Ranau and nearby Kundasang,” he explains, peeling layers of newspaper from the back of a newly made matrix. “When Jakarta’s band and punk collective Marjinal came to play here in 2013, I hosted one of their workshops right here in this room. Marjinal taught us the basics of woodcut printing, and I was blown away by the beauty and versatility of this style. That’s how we got Pangrok Sulap started, and we developed our own style and designs from there.”

“Look at this,” Leong says as he walks to his library and pulls out a volume on the work of Taring Padi, an art collective, that is an influence for his own group. Hailing from Yogyakarta, Java, Taring Padi is known for its grassroots involvement in Indonesian politics and its provocative, proletariat-focused woodcut artwork. Freddy, who has been quietly at work rolling black ink over one of the wood matrixes, chimes in. “Punk has more urgency when I immediately understand songs’ lyrics,” he says. “Foreign bands singing in English are, of course, influential because they invented the genre, but their lives and backgrounds are very far from ours,” he says. That’s the reason why most of Pangrok Sulap’s artwork uses Bahasa Malaysia, the official language of multi-ethnic Malaysia, to convey their messages.

Action, as Freddy mentioned, is not just limited to the production and sale of slogans printed on posters and t-shirts. Pangrok Sulap travels around Sabah, spreading revolutionary messages to as many people as possible through their art. Leong and Freddy tell me about a series focused on illegal immigration from Indonesian Kalimantan. In one project, the group focused on Indonesian immigrants selling cheap contraband cigarettes in Sabah. “We printed a series of posters to remind people how important it is to stop buying from illegal immigrants and support our locally produced cigars. Our tribal elders still hand-roll them as one of the main sources of their livelihoods,” Leong says. Cigars are sold at Ranau’s market, where the art punks plastered their posters. One depicts two old women in conical hats holding a round basket full of kirai asli, the original Kadazan-Dusun cigars. A sentence in Bahasa Malaysia reads, “If you want your own race to prosper, you must buy your cigars from these aunties.”

“We knew exactly that hanging posters with no permit was illegal,” says Freddy. “Of course, they were eventually taken off the walls. At least we managed to have the eyes of our local community peeled on them for a short while.” Pangrok Sulap has also experimented with installations. Using metal wire, the punks hung textbooks from the ceiling of one of Kota Kinabalu’s art galleries, placing them above life-sized cardboard children with outstretched, empty hands. “They represent the children of Filipino migrants without papers that, as they have no civil status and are invisible to Malaysia’s government, can’t go to school and even get the most basic education,” Leong says. In a land almost entirely lined by the porous coastal border of the South China Sea, this is just one of the problems that migration across modern borders has brought to the home state of Ranau’s punk rockers.

The existence of this small group in rural Borneo could very well represent one of Asia’s last bastions of punk-rock hope. If punk can influence young minds to think and act in ways that challenge real, local social issues, rather than merely reproducing the music of global punk’s subcultural dupes, then punk really isn’t dead.