It’s dark and rich, with that trademark sludge at the bottom of the cup. But in a part of the world where rivalries run deep, everyone has their own name for Turkish coffee.

There is, as one would expect, no Turkish coffee in Armenia. Soorj, that is, coffee prepared in a long-handled Jezve coffee pot, is referred to either as Haykakan (Armenian) or, to be more euphemistic, Aravelyan (Eastern). Arab coffee is easy to identify because of the cardamom, but its northern neighbour, however we call it, is more ambiguous. After nearly seven months living in Armenia, I am still haunted by the first day when, bleary and decaffeinated, I asked for Turkish coffee in a Yerevan café. How could I? The waiter in question still remembers, and when I order from him now, I am triply careful to stress the drink’s fundamental Armenian-ness—Shat haykakan Soorj, Hayastanum, Hayastaneets (very Armenian coffee, in Armenia, from Armenia). “How do you make Turkish coffee?” begins a Soviet-era Radio Yerevan joke. “Simple–burn the coffee crop and then lie about it for a hundred years.”

For a term so restricted in use, the Armenian term Soorj may have quite cosmopolitan origins. The word may be onomatopoeic, Soorj being the slurp made by a contented coffee drinker. In troubled areas of the South Caucasus, the etymology is an appealing one. “Turkish Coffee, Armenian Coffee; it’s all bullshit anyway” summarised a Yerevan taxi driver named Tigran. “Coffee’s from Ethiopia. Or Arabia. Or somewhere. Either way, unless I see coffee growing right here, right now, I can’t call it Armenian”.

WHEN WE TALK ABOUT TURKISH COFFEE, WE’RE NOT REALLY TALKING ABOUT COFFEE

A couple of years ago I visited Abkhazia, and under the arches and palm trees of Sukhumi’s seaside promenade, I ordered Turkish coffee. A Turkish cargo vessel stood on the horizon, punctuating the blue Black Sea as it gave way to clear skies. Hakop and his moustache bristled with indignation. “It may be Turkish when I buy it,” said the Armenian café owner, “but when it comes out of the packet, it becomes Abkhazian Coffee”. The boat’s prow nodded in agreement. I shut up and drank.

Of course, when we talk about Turkish coffee, we’re not really talking about coffee. Coffee is barely the surface. As the Soviet Union dissolved around them, the peoples of the South Caucasus endured vicious ethno-territorial conflicts and economic despair. Blood was spilt with thousands of deaths and bad blood remains in South Ossetia, Abkhazia, and Nagorno-Karabakh, which account for three of the four frozen conflicts in the post-Soviet space. In the byzantine world of the Soviet Union’s nationality policy, the concept of authenticity was greatly valued. Ethnic groups which qualified as titular nations—to whom an autonomous region or republic could be dedicated—often had to be autochthonous, the proven indigenous inhabitants of their territory. It is no surprise that a number of the first leaders of the Republics of the South and North Caucasus were historians by profession. The nation was primordial, as were its customs, its language, and potentially its cuisine.

These views have no doubt been entrenched by recent ethnic conflicts, or at least the collective memory of them.

THE ARMENIAN AVERSION TO TURKISH COFFEE IS A LEGACY, IN ITS OWN SMALL WAY, OF THE ARMENIAN GENOCIDE

The Armenian aversion to Turkish coffee is a legacy, in its own small way, of the Armenian Genocide of 1915 and the Nagorno-Karabakh war with the Turkic Azerbaijanis from 1988-1994. After all, what food, a Syrian-Armenian refugee in Yerevan asked me, could Turks possibly call their own? As the descendants of nomadic peoples from Central Asia, he claimed, only meat and dairy products were truly Turkish cuisine. Urban legend has it that a fast food restaurant in the northern Armenian city of Gyumri took it one step further. When embroiled in a court case for using McDonald’s branding and logo, the shrewd manager contended that he could not remove the corporation’s logo from his storefront. His McDonald’s M, was not a letter after all, and instead symbolised the twin peaks of Mount Ararat, sacred to all Armenians.

Yet even in Armenia, where 98.1% of the population are ethnic Armenians, views are far from unanimous. One of the country’s 2,769 members of the Assyrian community, Arman Gevargizov, sat in his garden in the small village of Dimitrov, garrulous, shelling walnuts and slicing pomegranates. He had just moved on to the subject of Assyrian cuisine when his dog, Zeus, interrupted him in a fit of barks. His mother approached Zeus to calm him and, after a few pats and whispering some sweet nothings in Neo-Aramaic, went indoors. “Zeus is peculiar”, mused Arman. “On a Sunday morning, he sits in complete silence, craning his neck to hear the church bells”. “A good Christian!” I laughed.

“I don’t think so,” sighed Arman, defeated. “I sometimes give him good pieces of pork as a treat, but he never touches them”.

Arman’s mother approached us with three small cups of black, sweet coffee. Assyrian coffee.

What was it, I asked, which made Assyrian coffee unique? Incredulous, and storming back into the kitchen by way of reply, she returned with a large bronze Jezve, still slightly warm from the stove. It was a family heirloom, and the Gevargizovs had no clue as to its age. Lovingly polished, it was inscribed with a Lamassu, an ancient Assyrian deity—a winged bull with a human head—and an inscription in Neo-Aramaic, still the vernacular of many Assyrians in Armenia. “Don’t ask me what’s written there,” snapped Arman. “I can’t read it, but I know it’s Assyrian”. From afar, Zeus watched on with respectful silence.

It was therefore entirely natural that, after leaving Armenia and arriving in Akhaltsikhe, I would wonder what to call the local caffeine fix. A city in Samtskhe-Javakheti, a province of South-Western Georgia near the Turkish border, Akhaltsikhe is known and—following the renovation of its castle and old town—publicised for its historic cosmopolitanism, a city with two synagogues, one mosque, Georgian Orthodox, and Armenian Catholic and Gregorian Churches. The province is known as Javakhk to its Armenian inhabitants, who form the majority of its population. Crossing the border with Armenia at Bavra, and passing Doukhubor villages, my companion from Yerevan dutifully pointed out Armenian shop signs in Ninotsminda and Akhalkalaki. “Armenian territory”, he noted. Stumbling through the ruins of Akhalkalaki’s fortress, I came across two empty bottles of Ararat Cognac lying in the snow, and was somehow tempted to agree.

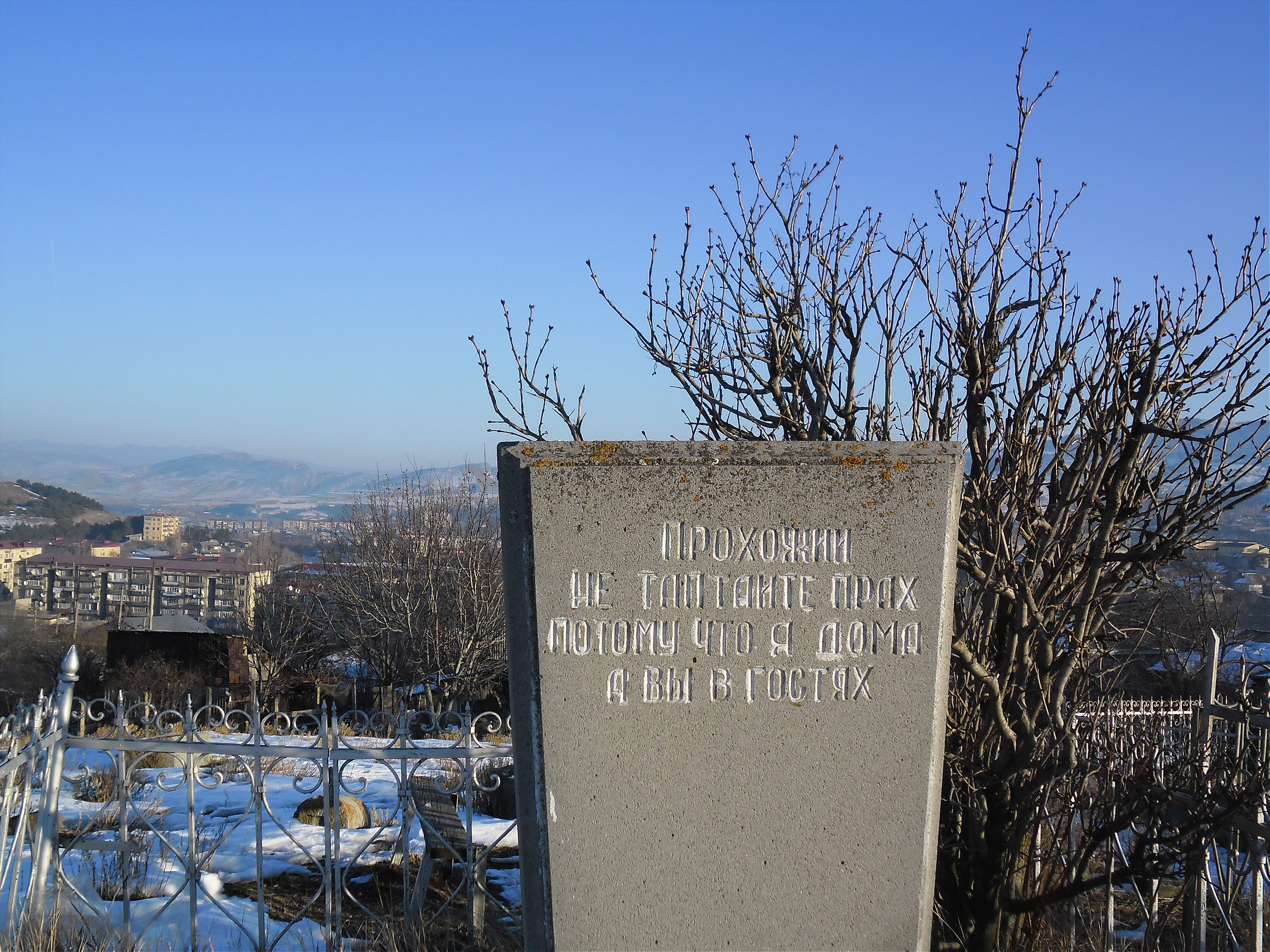

Yet all is not well in Akhaltsikhe, despite its cosmopolitan facelift. Samtskhe-Javakheti’s Armenian population claims discrimination, that they are deprived of cultural and linguistic rights. Much of Southern Georgia is heavily populated by ethnic Armenians and Azerbaijanis, and some Armenians have demanded autonomous status. Georgians, wary of ethnic secessionism after their experiences in South Ossetia and Abkhazia, do not react positively. They sometimes declare Armenians to be guests in the region, the descendants of refugees from Ottoman Turkey: not indigenous, and therefore not qualified for autonomy. A pressing concern for local Armenians is the ownership of church property in the region—their grievances focus on former Armenian Churches which, following renovation, now belong to a Georgian Orthodox congregation. Akhaltsikhe’s church of Surp Nshan, on a summit across the river from the Rabati, or old town, is a case in point. It’s not difficult to gauge local opinion. The local taxi drivers, four of whom I talked to while visiting the church, will readily pontificate. Georgian taxi driver Zurab lit up and sputtered in unison with his aging Lada as we crept through the backstreets. His nationalism reached new depths as we ascended the hill to Surp Nshan. “The tongue has no bone in it,” he declared, “so you can say what you please”. Surp Nshan was an ancient Georgian church—only the Armenian inscriptions on its facades had been added later (“The builders, you see, were Armenians”). Georgii, an Armenian taxi driver, was incensed, and whisked me away to Akhaltsikhe’s Armenian cemetery, whose gravestones bear images of Surp Nshan. “Even the dead agree,” he sighed. “And they rarely lie”. Simon Leviashvili, one of the eight remaining Jews in Akhaltsikhe, offered a flippant solution as we admired the city view from a Rabati sidestreet: “Simple. If they can’t sort it out, make it a synagogue”. That evening, I sat in a coffee shop with my notebook, and grudgingly ordered a Nescafe. That, at least, was universal—in a Unilever sort of way.

Travelling through the dramatic, photogenic gorges and canyons which carve their way across this region of Georgia, one could be forgiven for not noticing the remains of man-made, stepped terraces in the valley floors. In some cases, these are the sole remains of Meskhetian Turkish villages, of 115,000 people deported to Central Asia in November 1944. The deportation of the Meskhetian Turks was one of the lowest moments of Soviet administrative paranoia: an act of pre-emptive retaliation against Muslim villagers of mixed extraction who were seen as a potential fifth column for nearby Turkey. Now estimated at 400,000, the Meskhetian Turks remain scattered across the former Soviet Union, unable to return to their ancestral homeland. Alongside the Volga Germans and Crimean Tatars, they were not included in Khrushchev’s pardoning of deported peoples, and their resettlement remained prohibited. As it had done for the Chechens and Ingush, the years of exile formed (and continue to form) a coherent national identity for Meskhetian Turks.

Forty-nine year old Mukhamad Khustushvili is a native of Samarkand, Uzbekistan—though in his heart, he stresses, he is from Samtskhe-Javakheti. Upon repatriating to Georgia in 1999, he opened a small restaurant in the city centre with his wife. His is one of roughly fifteen Meskhetian Turkish families living in the area, and he is one of less than a thousand who have managed to repatriate. The Turks have returned to southwestern Georgia, although now they are lorry drivers, market traders and labourers from Eastern Anatolia, from cities like Ardahan, Kars and Trabzon. Mukhamad’s modestly successful restaurant is stocked with numerous brands of Russian vodka and menus in English, Georgian and Turkish. Khutsushvili is exquisitely aware of his people’s chequered history—who they were, and who they became. He notes with palms upturned that Akhaltsikhe’s monuments to inter-ethnic harmony—its mosque, synagogues, and churches—were all built before 1944, the year of deportation. He talks and reminisces as though he were an omen. We drank sweet black tea from Turkish tulip-shaped glasses, as if to illustrate the point.

Remembering my last Armenian coffee, I ask Mukhamad about concerns that resettlement of Muslim Meskhetian Turks could raise tensions with the local Armenian majority in Samtskhe-Javakheti. He swats the question away with the palm of his hand, pantomiming its irrelevance.

“I am from the Caucasus—and have a lot in common with these Armenians. Meskhetians have a Caucasian temperament; we will not grovel before anybody—unlike those Turks across the border.”

They could integrate, he continues. They could make it work. He says he certainly had in his restaurant. “Our food is even Georgian!” he exclaimed “Georgian… but Halal.”

GEORGIA IS KEY. WHOEVER CONTROLS IT CONTROLS ALL THE CAUCASUS

“Even if three percent of us would return, that would be something. A land grows fallow without its master; a house starts to collapse. If the great powers of the world—Russia, America—want us to return, we’ll return. But it won’t be for the right reasons”

“Georgia is key. Whoever controls it controls all the Caucasus.” The whole country, he lamented, was going to Khash (his place, Muhammad hastened to add, served the best in town).

The tea glasses were cleared, and one of the next generation of Khutsushvilis came, bearing chocolates and small cups of sweet, black coffee. “Teşekkürler”, I said (thank you in Turkish)—and was met by a wide, infant smile.

“Turkish coffee?” I asked Mukhamad, taking the cup from his son.

“Of course,” he replied, raising his index finger. “Meskhetian Turkish coffee.”