China is on a stadium-building binge in Africa. What will the glut of cookie-cutter stadia do to the African game?

In Maputo, the “Garden for Sculptors” behind the Museu Nacional de Arte on Avenida Ho Chi Minh has become a kind of prison yard for Mozambique’s various Ozymandiases, a semi-public dumping ground where colonial monuments now crumble quietly away. A marble European baroness reclines in thick robes, the grasses growing up around her base. Both of her arms have been lopped off, but her amputated left hand still touches the midriff of a black male slave crouched in a loincloth by her side. Nearby, a decapitated Lady Justice presides over a small patch of weeds and bare earth. No longer public art, but not quite garbage, these are the monuments which were extracted like rotten teeth from the city’s squares and public buildings when Portuguese colonial rule finally ended, but which nobody could quite bring themselves to destroy.

One August afternoon I chanced upon the newest addition to this miserable collection. Facedown in the dirt lies an enormous bronze angel, wings stretched high over its head like some kind of massive avian Academy Award. Walking around it to its jagged base, ripped from wherever it had once been rooted, I found that the figure was completely hollow. Inside there was a small plaque whose Chinese characters I could not read. Intrigued, I went back into the museum, and asked the receptionist there where this gigantic statue had come from and why it had been dumped here. He answered with the air of someone patiently explaining something very obvious to someone very dull. The angel had been erected in 2011 by the Chinese government in front of the new national soccer stadium, to give the place some character and serve as a kind of focal point. But when Mozambican officials saw that the statue had “a Chinese face”, they decided it wouldn’t do to have a Chinese angel in front of their national stadium, tore it down, and trucked it into town to join the rest of Maputo’s unwanted colonial trappings in the Garden for Sculptors.

Mozambique’s new national stadium, Estádio Nacional do Zimpeto, is on the outskirts of Maputo, not far from the Chinese-built international airport. The Chinese have also overseen the construction of the new parliament building and a new “Palace of Justice” in the last few years. The main institutions through which a sense of Mozambican national life is constructed—the laws of the nation, international departures and arrivals, and its most spectacular public moments of heroism—now take place in Chinese-built structures.

If you want to see the heart of China’s soft-power push into Africa, you’ll find it in the continent’s new soccer stadia.

China completed its first stadium construction project in Africa in 1970 with the opening of the 15,000-seater Amaan stadium in Zanzibar, Tanzania. That modest structure marked the start of four decades of so-called “stadium diplomacy” by China across Africa, the Caribbean, Asia and the South Pacific. Today there are few countries in Africa that don’t have stadiums built by the Chinese government as gifts or with concessionary loans. There was a noticeable acceleration in construction in the late 1980s and early 1990s, as Senegal, Mauritania, Mauritius, Kenya, Rwanda, Niger, Djibouti and the Democratic Republic of Congo (then Zaire) all got shiny new stadiums. But the real boom has come in the last ten years. Three recent host nations of the African Cup of Nations—Angola, Gabon and Equatorial Guinea—have had all their tournament stadiums built for the purpose by China. All three happen to be nations with significant off-shore oil reserves ruled by autocrats and small elites structured around a ruling family. But countries with more modest natural resources and more democratic structures of government—Ghana, Tanzania, Zambia and Malawi for example—have also found room for new Chinese-built stadia within the last decade, as part of China’s much-documented program of economic expansion.

IN RETURN FOR STADIA, CHINA GAINS AN ENTRÉE INTO THE HIGHEST CIRCLES OF GOVERNMENT

The impact of this most concrete form of soft diplomacy is difficult to assess in terms of hard cash. But there’s little doubt about how it’s supposed to work. For relatively small outlays—usually well short of $100 million—China constructs a sterile national arena that can be opened with long speeches and presidents in tailored suits kicking balls for the cameras, in return for sweetened access to natural resources, votes at the United Nations and the marginalization of Taiwan. Domestic politicians point to highly visible new infrastructure as evidence of their success as managers of the national development agenda; China and Chinese businesses gain, at the very least, an entrée into the highest circles of government.

All of this is officially carried out in the name of friendship, of course—there’s one Stade de l’Amitié, in Libreville, Gabon, and another Stade de l’Amitié in Cotonou, Benin. Fortunately, the pious fraternal rhetoric attached to the openings of these stadiums has on occasion been punctured by moments of mutual cultural befuddlement. In 2007, for example, it was gleefully reported that at the opening of the new cricket ground in Grenada in the Caribbean, the Chinese ambassador Qian Hongshan and assorted dignitaries displayed visible discomfort as they sat through the Royal Grenada Police Band’s stately rendition of the national anthem of the Republic of China—a country more commonly known as Taiwan. The bandmaster took the rap. “This unfortunate error breaks my heart,” said the Grenadian Prime Minister.

By 2010, over 50 stadia had been built with Chinese government support across the continent, and despite the always-repeated insistence that another new stadium is “needed” we are now approaching stadium saturation point. If there was a Millennium Development Goal for stadia per capita, Jeffrey Sachs would probably turn up one morning at one of his Millennium Villages and find that the Shanghai Construction Group had knocked up a 55,000-seater next to one of his newly dug wells, christened it Le Stade de la Fraternité, and carted off all the hardwood trees from the forest.

If the “agenda” of stadium diplomacy has been concealed, it hasn’t really been hidden very far from view. Yet all the focus has been on the not-especially-mysterious question of what it is that China expects in exchange for all these stadia, rather than on what this addition to virtually every African capital city means culturally and historically, let alone whether or not they’re actually enjoyable places to watch a soccer match.

ON THE PLAQUE: “THE FRIENDSHIP BETWEEN CHINA AND MOZAMBIQUE WILL LAST FOREVER LIKE THE HEAVENS AND THE EARTH”

It took three separate minibus rides from downtown Maputo to reach Zimpeto. I had arrived from Scotland the previous day and was finding Mozambican Portuguese tough going, but this was match-day, with Mozambique hosting neighbors Tanzania, and it was easy enough to find my way by following the crowds of people in bright red shirts and scarves wrapped around their heads, and the constant parping of vuvuzelas. Inside a vast paved complex ringed with a chain-link fence, a huge grey concrete bowl rose up. When I first saw the new home of Os Mambas, I thought those aliens from District 9 must have finally got their spaceship working and parked it in Maputo. Inside stood a suitably intergalactic prophecy, in Mandarin and Portuguese, written in red letters: “Amizade entre a China e Mozambique irá prevalecer como o céu e a terra.” Translation: the friendship between China and Mozambique will last forever like the heavens and the earth.

With five minutes to go until kick-off, there was virtually nobody inside the stadium complex. Outside the perimeter fence, the crowd thronged through bars and shebeens, in and out of minibuses, picking up cold beers from sellers carrying coolers along the roadside and others in leather jackets flogging knock-off Mambas merchandise. From the street, Zimpeto and its arid concrete approach had the feel of a mausoleum.

THE ATMOSPHERE IN ZIMPETO WAS SO SUBDUED, DROWNED BY THE VASTNESS OF THE PLACE

Once inside, the Mambas fans sat stiffly together high up in one huge uncovered stand of plastic seating. It was a significant match, with Mozambique’s hopes of making it to the 2013 African Nations Cup resting on the result, but the stands at either end of the pitch were completely empty. In the town center, I’d seen motorists screaming their devotion to their team out of car windows, pounding their horns at one another and piling fellow supporters into their backseats. The atmosphere in Zimpeto was so subdued, drowned by the vastness of the place, that I could hear the players calling out at each other down on the field. A huge athletics track circled the pitch, and far off in the distance, in the covered stand for VIPs and the away supporters, we could see a small cluster of Tanzanian fans clad in blue whose cheers reached our ears once or twice, muffled by the great gulf of empty space between us. The Mambas drew 1-1, but eventually won the tie after a very tense penalty shoot-out. The celebrations in the stadium were noisy but brief, as jubilant fans dashed back out into the street where the real party had already started.

A couple of weeks after the game I met up with Tico-Tico, Mozambique’s record goalscorer, recently retired. He told me that while he hoped the team would win the next round and make it to the African Nations Cup to be held in neighboring South Africa, he feared such success might give the false impression that the game in Mozambique was being well-run at the national level. Likewise, the new stadium gave a misleading picture of an ambitious and competent national association, when in fact the Mozambican governing body was in need of radical restructuring and reform if the country was to make the most of its footballing talent. A couple of months later, Mozambique traveled to Marrakech and were soundly beaten 4-0 by Morocco.

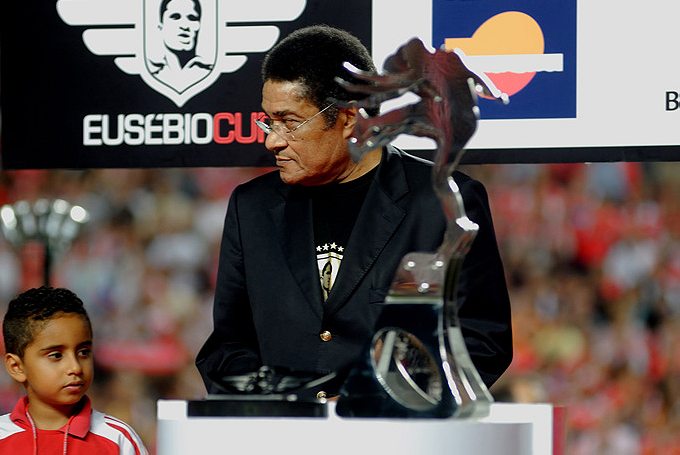

By and large, the venues that were replaced as national stadiums during the great wave of stadium diplomacy were those that had been built or repurposed after decolonization in the 1960s. Many of these had hosted national independence celebrations. And there was legendary soccer that took place in them. The original Estádio Salazar (renamed Estádio da Machava after independence from Portugal in 1975) had been inaugurated in 1968 with a friendly match between Portugal and Brazil. Portugal was captained by a black player from Maputo—Mario Coluna. The Brazilian side included Carlos Alberto and Tostão. The great generation of Mozambican footballers of which Coluna was a leading light—Eusébio, Matateu, Vicente Lucas, Hilário da Conceição and Alberto da Costa Pereira were others—never played for the Mozambican national team (it couldn’t exist under colonialism and so instead they forged Portugal’s greatest ever team) but at least some of them played right in front of their countrymen at Machava that day in 1968.

Sad that I had come to Maputo too late to see the Mambas play at Machava, I wrote a friend shortly after the Tanzania match who had been to a World Cup qualifier there some years previously. I’d heard a rumor, incorrect as it turned out, that the old stadium was to be demolished. “I’m not sure that Machava can actually be ‘torn down’,” wrote my friend, “since it was just a hole in the ground to begin with. Perhaps it can be filled in.”

The replacement of venues whose crumbling terraces are layered thick with national history by soulless flat-pack “friendship” stadiums is not unique to Mozambique. In the 1960s, Lusaka got Independence Stadium. Nowadays, Zambia’s Chipolopolo (copper bullets) play their games at the new Levy Mwanawasa Stadium, which looks an awful lot like Zimpeto and happens to have been built in Ndola, an industrial town close to many of the country’s most important mines.

From this year, Malawi’s national team, the Flames, will play home matches in Lilongwe, a gridded city of embassies and fenced-off NGO headquarters, rather than the commercial capital Blantyre, where the national team has always played since Malawi’s independence.

NOWADAYS, NOBODY WOULD DESIGN A SPORTS VENUE THAT LOOKED REMOTELY LIKE KAMUZU STADIUM

Lilongwe’s Kamuzu Stadium was named after Kamuzu Banda, the eccentric Chicago-educated family doctor who ruled Malawi as a one party state for thirty years. The Rangeley Stadium constructed in the 1950’s took its name from a British colonial administrator. For a few brief years following independence in 1964 it was known as the National Stadium, before Banda purged all political opposition and set about transforming the country into his personal fiefdom: major highways, hospitals, schools and of course the national stadium were all named after him. After Kamuzu was voted out and multiparty democracy installed in 1994, the new president Bakili Muluzi renamed everything that had borne Kamuzu’s name as a way of exorcizing the decades-long cult of personality that had set in. But Muluzi himself liked having institutions named after him, and soon the re-christened Chichiri Stadium was the home ground of the Bakili Bullets. When Muluzi was replaced by Bingu wa Mutharika, who liked to style himself as a kind of second Kamuzu, the venue was renamed Kamuzu Stadium after the self-professed “lion of the nation” and the Bakili Bullets became the Big Bullets.

The old stadium is formed by a low grandstand and six gently sloping massive concrete slabs with large steps cut into them, and it holds anything from 50,000 to 100,000 people, despite having one end where there is no kind of structure at all, just a large rusty billboard and a few trees. There are no seats, except in a small VIP section stacked with pricey-looking chairs and sofas that index the relative potency of the backsides sitting on them by the quality of their upholstery. Nowadays, nobody would design a sports venue that looked remotely like Kamuzu stadium.

Periodically, FIFA and CAF have sent their inspectors along and these men leave spluttering dire threats of banning and closure, aghast at the appearance of large cracks, the patchy pitch, and the lack of security (the stadium is in more or less continuous use by ordinary members of the public who keep fit by running up and down the thousands of concrete steps). It certainly didn’t feel like the safest stadium I’ve been in, but there’s never been a disaster there, and there was something wonderful about the regularity with which the pompous international bureaucrats would huffily pronounce the place unfit for its purpose, only for it to host yet another joyous and peaceful afternoon of football the following week.

In 2006 I found myself commentating live for TV Malawi on a match between the two bitter Blantyre rivals, Big Bullets and the Mighty Wanderers, at Kamuzu, a scrappy 0-0 settled after an interminable penalty shootout. The fans banded together to form great swaying clusters all around the terraces, bounced and chanted throughout the game, danced in the aisles and roared with wonder, derision and disbelief for fully two hours.

The new national stadium in Lilongwe will be paid for with a $70 million concessionary loan from China. Jimmy Kainja, a writer in Lilongwe, told me “It may take time for a lot of fans and certainly me [to] feel the real loss after leaving Kamuzu stadium,” which he called the “spiritual home” of the national team. The new stadium, on the other hand, is part of a series of high-profile Chinese building projects in Lilongwe that includes a new parliament building and a large 5-star hotel. The two countries established diplomatic relations for the first time in 2008. The stadium is being built in a similar style to the new Estadio do Zimpeto in Maputo, and has yet to be given a name.

[Header image by: Reuters/Amr Abdallah Dalsh]