Thomas Dworzak talks about his obsession with the little things in Instagram

Thomas Dworzak, German-born polyglot and leading member of the louche fraternity of war photographers in the Caucasus, is not a trivial man. Yes, he’s excitable and headstrong: when I’ve shared a table with him in homes or at Pur Pur in Tbilisi or Delicatessen in Moscow, he’s always been an unfiltered kinesis of wild gestures and strong opinions blasted through clouds of smoke. But his work, from the mass graves of Chechnya to the flooded Lower Ninth Ward, could be Capa. Or Rodin: his subjects hunch and writhe like the Burghers of Calais, turned to statues in a moment of anguish. It’s powerful, permanent photography.

So why does his latest project involve, in part, curating a bunch of teenagers’ selfies on Instagram?

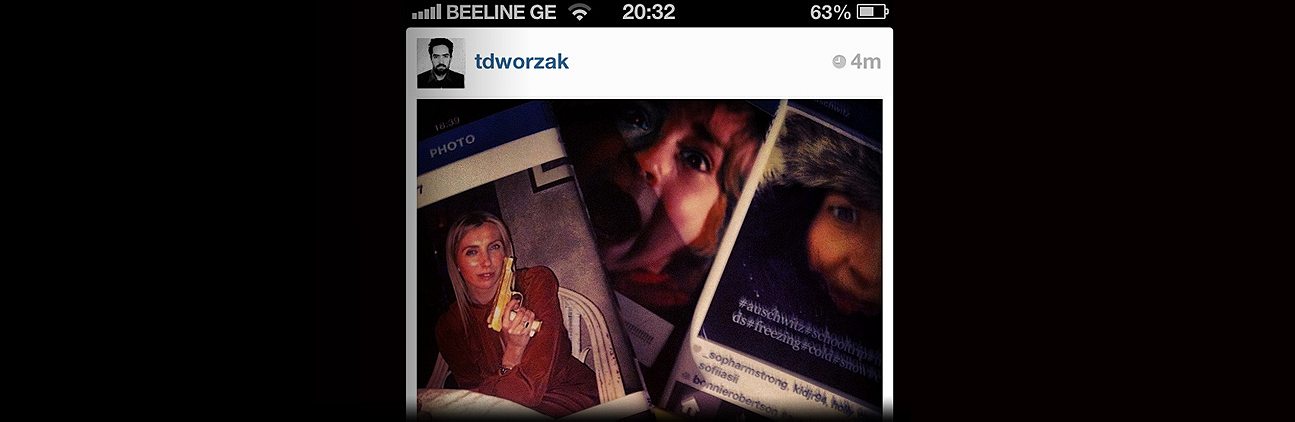

The answer comes tomorrow night, May 31, in Tbilisi. In the same salon of the Writers House where the Georgian Writers Union received John Steinbeck and Robert Capa in 1947, Dworzak will show his latest obsession: a series of chapbooks—paperback, printed—of Instagrams he curated from a somewhat delirious range of hashtags. They aren’t available online at all; lord knows if you or I will ever actually see these things. But I talked to Dworzak this weekend about Instagram, dictators, tannings beds, his latest assignment for National Geographic, and the need to get the hell out of the Caucasus from time to time.

Roads & Kingdoms: You just got back from the North Caucasus on assignment for National Geographic. Were you Instagramming while you were out there?

Thomas Dworzak: If you are an Instagrammer, I think it’s generally considered a privilege when you’re allowed to use the National Geographic, New Yorker, Time Magazine Instagram account. [But] I didn’t want to do it in this case. I’m not against it, I’m not in favor. I’m weird about this stuff.

R&K: You’re weird about this stuff?

TD: I don’t know, I’m not super comfortable with all of it. I have an Instagram account but I only accept people I know. I don’t want to be visible with the little odd bits and pieces of my life. I don’t want to have a situation where I go somewhere, I take a picture of something and somebody says “why didn’t you call me? You were in town.” That was a classic Facebook problem but I guess Instagram will be the same. I don’t even have Facebook, so I think my problems are lacking.

R&K: It’s a little ironic, then, what you’re doing for Tbilisi Photo Festival.

TD: I’m not into social media for the social sense because it’s not something I’m used to. I’m too old, I’m not comfortable with it. But I checked it out and by checking it out I’ve come across documents of social situations that I think are very remarkable. So I started collecting Instagram screenshots.

It’s not like, oh my God, I can snoop into people’s private lives. No, I think there’s more to it, I think there’s a real sensitivity to it. As a photographer, I’m more interested in what kind of access I can get to certain things, how I am in relation to what I’m photographing. I mean, I’m a big embed fan. I love embedding, I love getting close to people and living with them, so there’s always a limit, there’s always a thing where you can’t go any further. So I was playing on that theme. That’s my Instagram exercise, if you will.

R&K: So it’s all screenshots?

TD: The way to do it is you do a screenshot of your own phone. The funny thing about Instagram as I understand it is, and there are people who are more specialized in it, is that it’s an ephemeral thing, it’s [always] moving. Something comes up and then it’s gone again, you can’t even really look for – I mean it’s very hard to look for anything. There are hashtags, but there’s billions of pictures and if they’re not hashtagged you can’t find them anymore. There’s no way of searching them. I guess Instagram itself has some sort of a picture recognition software, how they get rid of the tits and dicks. If you try uploading a breast, it will disappear. I’ve tried it.

So I find it exciting because… I mean I can Google interesting pictures and try and find them and put something together, that’s what a photo editor does. With Instagram there’s always this feeling that if you’re too late… The first book I did was on the pope election. I just threw it together, it’s nothing, it’s unpublished and I don’t think it should be published in that sense, but so the night the pope got elected, for some fucked up reason, I don’t know why, I started hashtagging what comes up with pope. And suddenly all this insane stuff comes up. People dressing themselves up as pope, people dressing their pets up as pope, people smoking pot like crazy and taking pictures of themselves, like with pot smoke everywhere. And then I sat down, watching TV, everybody was on St Peter’s square, taking pictures of the pope on the balcony, very bad pictures from far away, and all blurry.

I don’t really know what I’m doing this book for, I haven’t figured out what to do with this stuff because obviously this is people’s pictures. It’s a bit like collecting people’s photo albums, it’s a little in that spirit, but I don’t think it should be published. For me, the whole point is a little bit in the exclusivity and in the tenderness. Everybody can go on Instagram and look at everybody’s pictures if you just spend enough time on it. So to take this and something that’s so fast and disappearing, to put it back in a physical book, and have it in a very limited edition or access. I mean you can only sit down and look at the little book, that’s it. I don’t scan it; I don’t distribute it digitally, no. I don’t want to do that.

R&K: Are you selling it, are you giving it to friends?

TD: Nothing, I just showed it to people, I don’t know… I think in a way, it’s something that has a real value as a document, it should remain, of this epoch. Whatever. I’m going to do nine books or twelve and that’s it.

R&K: How many have you done?

TD: I’ve done nine so far, I might do three more. I don’t know, I don’t think I’m going to do anymore. I spend two days on one of them. I’m collecting pictures for a month, on and off, whenever I have time or I’m bored.

It’s the only place where there’s actually a dialogue between a North Korean official and Western punks.

R&K: So you did #pope, what are some of the other ones?

TD: I did #habemuspapam, that was the first one. Another one I did was [head of the Chechen Republic Ramzan] Kadyrov’s Instagram account, which I find actually interesting because early on he was doing it unprofessionally, he wasn’t trying to use it as a sort of PR tool. I came across it very early, the old account. There are two [books] that are actually political self-representation. One is Kadyrov and the other one is a kid at the North Korean embassy in Berlin who puts up official pictures. What I found interesting more than the pictures—which is sort of the crazy North Korean stuff on [Kim Jong Un], president or whatever he is—there’s the whole dialogue section which I copied a lot of, which to my knowledge is the only place where there’s actually a dialogue between a North Korean official and Western punks or something. They sort of insult each other but also ask each other very interesting questions. It’s a bizarre exchange. So the North Korean book has a lot of emphasis on the comments. The other ones I didn’t do much text.

R&K: Which part are you doing for the Tbilisi Photo Festival? Is it the Kadyrov part, is it a collection?

TD: I didn’t do it for the photo festival. I said to them, let’s not have a [photo] exhibition. If you want something from me, why don’t we put a table and we put these books and people can look at the books? I think that’s the right way to do it.

It’s all things that are somehow related to what I’m doing in my “real work”, I’ve covered the pope before, I’ve obviously done Kadyrov, I have done North Korea. I mean David Guttenfelder is doing an amazing job on Instagram from Korea. It’s beautiful. But I’m not so interested in professional photography from North Korea. Kadyrov is the most professional because he has his personal photographer who takes pictures of him doing all this weird stuff, when he kisses an animal or something. So that’s another guy doing it, but I really like it if it’s sort of educated amateurs. Because what’s nice about this is also the aesthetics. They take decent pictures. You can look at it, it’s not totally off.

R&K: Even the kid from the North Korean embassy?

TD: Well the kid from the North Korean embassy actually puts up stuff that is given to him. But with the North Koreans it’s really more the dialogue in that side. But there’s these weird things coming in, like there’s this one German kid who’s a fervent supporter of North Korea, constantly loves all the pictures, he’s this weird guy and posts the pictures up for himself and you just look at the guy, it’s just so funny. It’s funny to see who the people are that make ‘likes’.

For a photographer, [the tanning bed] is a place you will never be able to take a picture. You don’t fit in there.

The next book I did was the most innocent one. I don’t know how I came across it, but there’s an incredible fashion for women, especially in northern countries—you never really know where it’s from but you sort of get a feel for who they are, what their names are, etc, so mostly Russians, Ukrainians, Germans and Scandinavians—to take pictures of themselves in a solarium [tanning bed].

So they’re inside the thing. For a photographer, that’s a place you will never be able to take a picture because you don’t fit in there. It’s sort of a private joke, ha ha ha, you have to take it yourself; I can’t take a picture. And of course it’s just all pictures of body parts in different fluorescent lights, but if you take 100 of them, it gives you a nice scale of all the colors in the world. That’s the dumb end of the whole [project], the unpolitical part.

R&K: It does sort of flatten everything… I mean when you have this one very weird little publishing platform, it kind of flattens dumb, political, profound and everything else.

TD: The pope was hilarious for me because like every idiot who does hashtag #dope that night thinks, oh #dope, let’s also do #pope…. I don’t know, it was very funny the whole thing.

I did another book on school trips to Auschwitz, like kids, because that’s sort of the forlorn generation, these hundreds of thousands of European school buses driving to Auschwitz every year. They’re like pictures from a school trip and then suddenly there’s this overwhelming drama of being in Auschwitz. I mean, so it’s like, I found it very tragic. There’s a few pretty sick things of course because they dress up as Hitler so whatever, but in general it’s very tragic. There’s something also, I don’t know, when you get into this, you don’t get into the closeness.

[Boston] had beautiful pictures, like really moody and suddenly they got this SWAT guy sitting in their living room.

I did one on the Boston thing because that’s sort of a classic. It has been used in the mainstream media, but it was nice. It was this whole sort of Rear Window, also because if you go to a place like Boston or the school kids that go to Auschwitz, it’s really those people who excessively use cellphone cameras, all the time, so you have an incredible choice of pictures to pick from. So Boston was amazing. Just the amount of pictures of SWAT teams through windows… And beautiful pictures, like really moody and suddenly they got this SWAT guy sitting in their living room.

The second volume of that is all the girls who write Free Djokhar on their hands, I mean there’s like hundreds of them, hundreds of white American teenagers who think that Tsarnaev is the sex symbol of the 21st century.

R&K: When you were in the North Caucasus, were you checking out the kids and their phones and just trying to see are they using it the same way?

TD: No, not at all actually because I really wanted to sort of… I had a really funny thing, I was riding from Vladikavkaz to Grozny and there’s this kid sitting next to me and suddenly I realize he’s actually liking every single picture on Kadyrov’s Instagram account. It’s just weird; I didn’t even want to talk to him. I took a picture of him and put it up on Instagram.

I think the Free Djokhar thing to a big extent is really a Western teenage Stockholm Syndrome.

I saw a girl putting up a Free Djokhar poster from a bus and then got out of the bus and was trying to catch her and she disappeared. She was like a normal, Western-looking kid. I think the Free Djokhar thing to a big extent is really a Western teenage Stockholm Syndrome or something. It’s got nothing to do with Islam or the Caucasus. The more I collected, I tried to exclude anybody who could have been from the area, my whole thing was to find people who had nothing to do with this.

R&K: So tell me how it’s going to go down at the festival, it’s literally going to be a table with these books on them?

TD: Yes, definitely the library and if someone wants to come, they can consult and they can take one and sit down.

R&K: So there will be no digital thing?

TD: No, definitely not digital.

R&K: All just printed?

TD: All just printed.

I’m not happy with what’s happening [in Georgia] but it’s not like, oh my God it’s so horrible to be based here.

R&K: Right now, what is going on in Georgia for you as a photographer? I talked with [Tbilisi Photo Festival co-director] Nestan Nijaradze a little bit about the elections and the politics of May 17th, but are you finding it a strange place to be based?

TD: Georgia is Georgia. I mean I’m not happy with what’s happening [but] for now, I’m here. I wasn’t here for the 17th, I think it’s ugly. On the other hand, it’s what people think and now it suddenly came out. It’s not like, oh my God it’s so horrible to be based here. It’s just that I’m not going to continue to deal with Georgian politics. It’s not my subject. I’m following Misha [Saakashvili] and when he’s gone he’s going to be gone. I mean I’m following on and off whenever I’m here I do something and then sometimes I make money. After him, I’m not personally interested in Georgian politics.

R&K: But you guys are not going anywhere?

TD: No, I’m staying here [for now]. I want to go to Iran, I’m working on it. I’ve always said I want a change anyway. Every five years I have to get out of the Caucasus, I have to get out of Georgia because it’s so absorbing. I need to force myself to do something else. That was independent from the elections. So next Spring, I want to do something else.