The struggle to remind the world of what happened in Nanjing in 1937. From photographer Amanda Mustard.

Photographer Amanda Mustard followed a long chain of contacts and helpers to arrive at her project on the survivors of the Nanjing Massacre. It started with her high school history teacher, who led her to read The Rape of Nanking by the late Iris Chang, whose mother would later help Mustard break down barriers and locate a handful of the last survivors of one of the most brutal chapters of World War II.

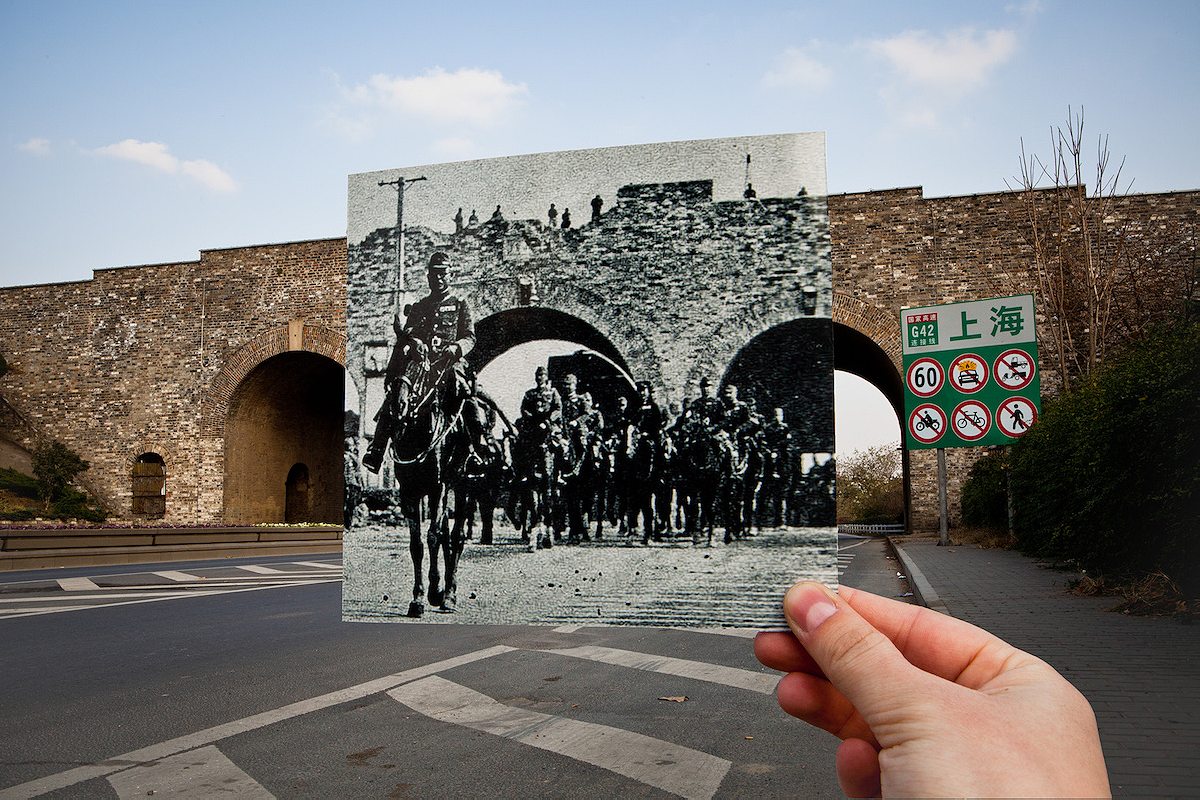

This Friday marks the 76th anniversary of the day Japan captured the then-capital of China and put its people to the sword. Some 300,000 people in the city died—most of them during the first six weeks of the occupation—according to Chinese estimates. There were international as well as Chinese witnesses to the unhinged grotesquerie of rape, lawlessness and murder, but to this day, Japan refuses to formally apologize. This intransigence has become a constant rallying cry for Chinese nationalists and an ongoing point of friction between two wary powers.

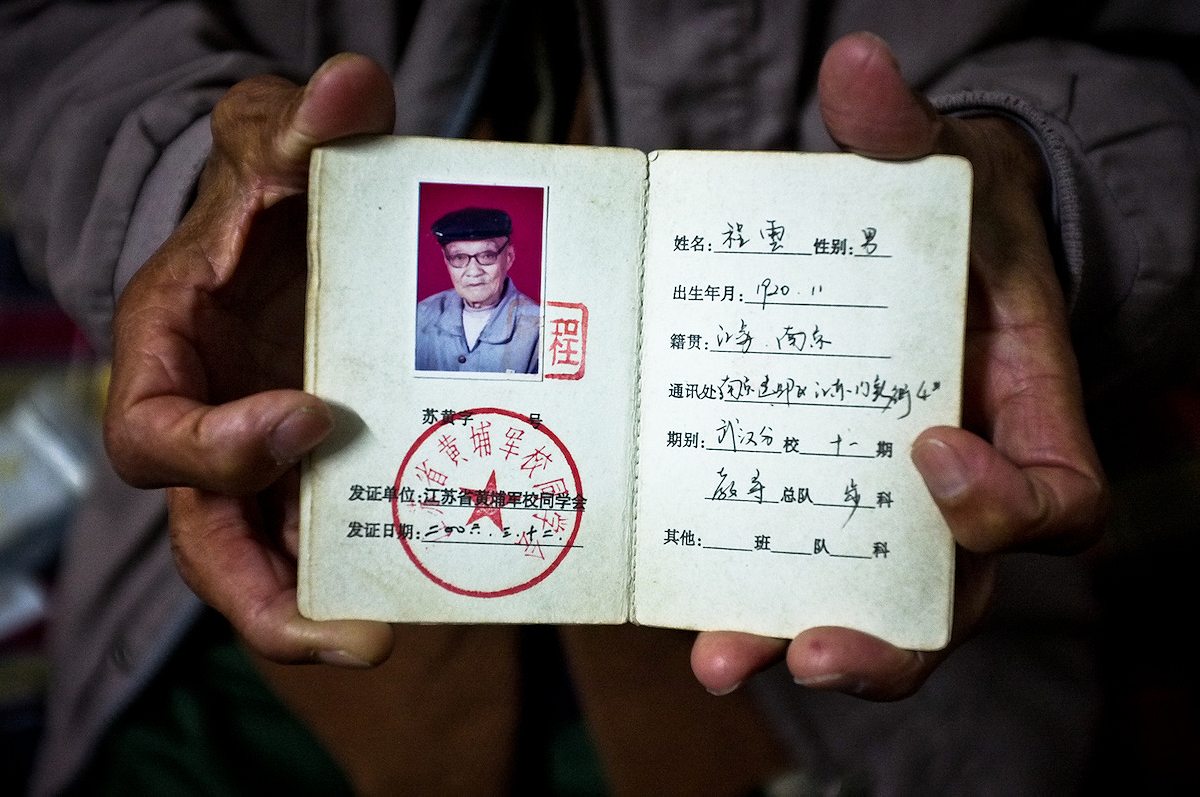

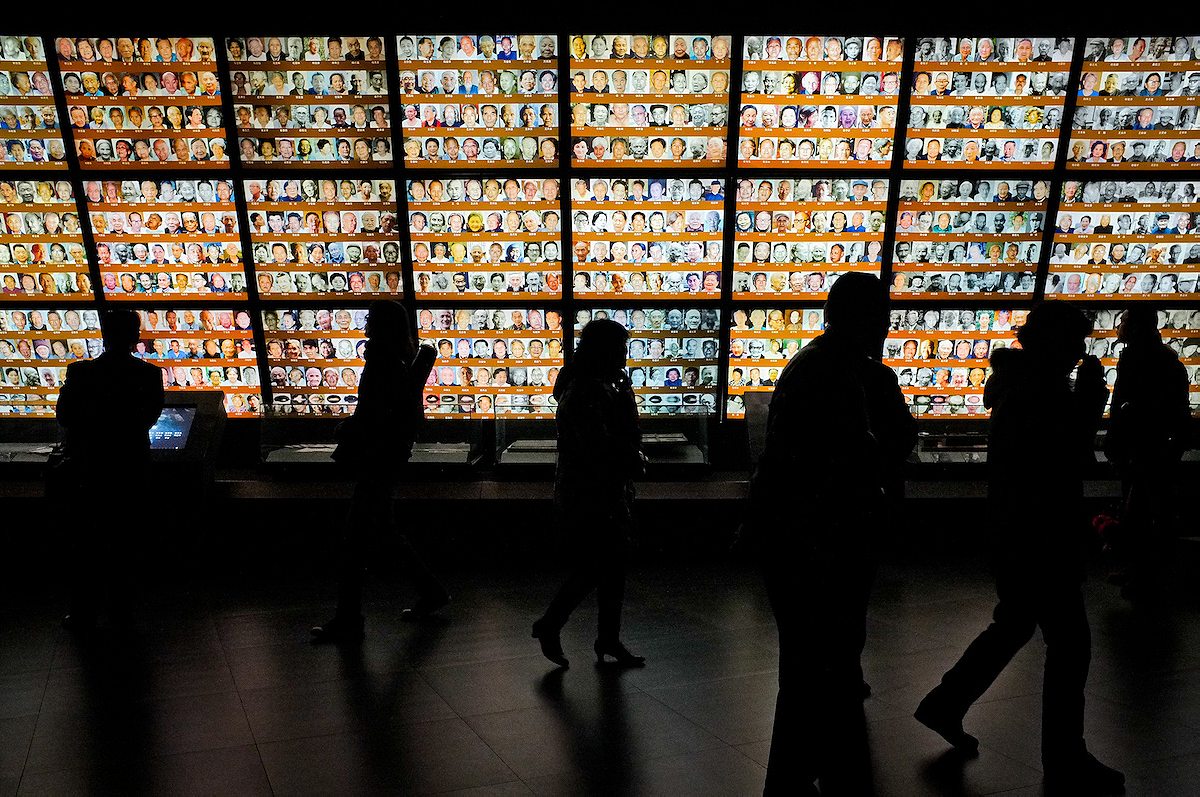

A crime on the scale of Nanjing is, at root, a constellation of individual tragedies. Which is why Mustard’s project, shot during the 75th anniversary last year, has such appeal. By the time Mustard flew from Cairo to Nanjing for this this work, only 200 survivors were still alive. It falls to them to keep the memory real, but in their old age, many face other challenges. They have been lauded as ‘war heroes’ by the Chinese government, which is keen to use them as reminders of Japan’s perfidy. But then there are stories like that of Cheng Yun, who is photographed below. His service as a Chinese solider in occupied Nanjing is celebrated at memorial events, but he has also been denied military pension benefits because he had been deemed anti-Communist earlier in life. At 93, he now survives by recycling bottles in a Nanjing slum, and is provided daily meals and care by his nephew. And so his story, like China’s, is still evolving, reminders not just of a terrible past, but also of a contemporary China that still struggles to provide dignity and freedom to all its people. The survivors of Nanjing have suffered too much to deserve anything less.