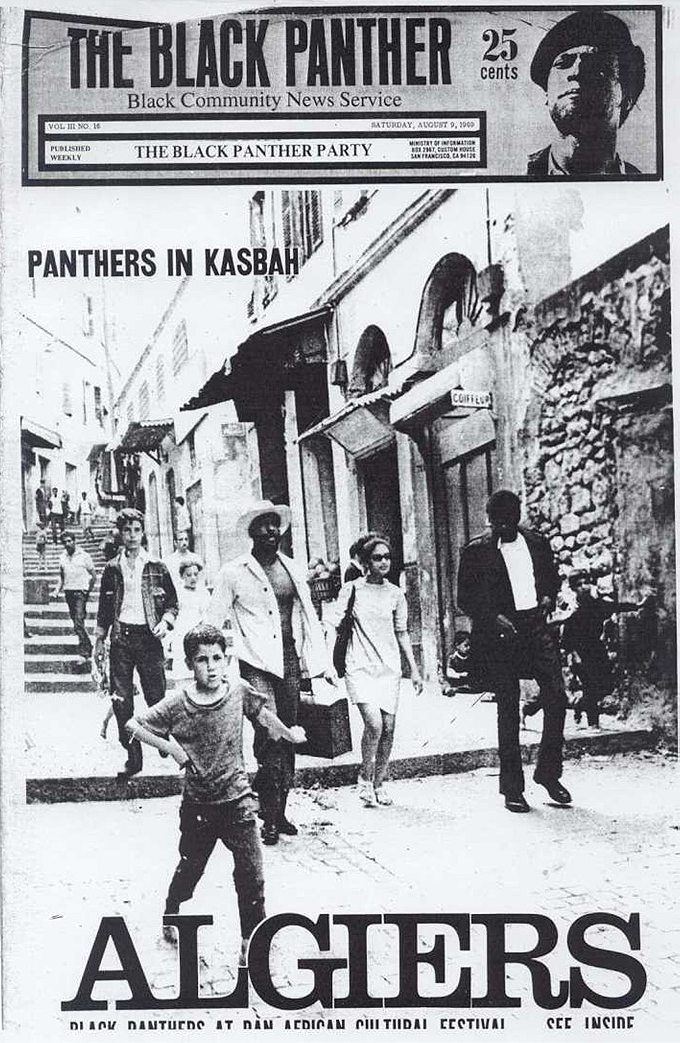

In the early 1970s, Algeria’s dictatorial president offered a home to revolutionaries from all over the world. Perhaps the most famous recipient of his generosity was the Black Panther “Minister of Information,” Eldrige Cleaver.

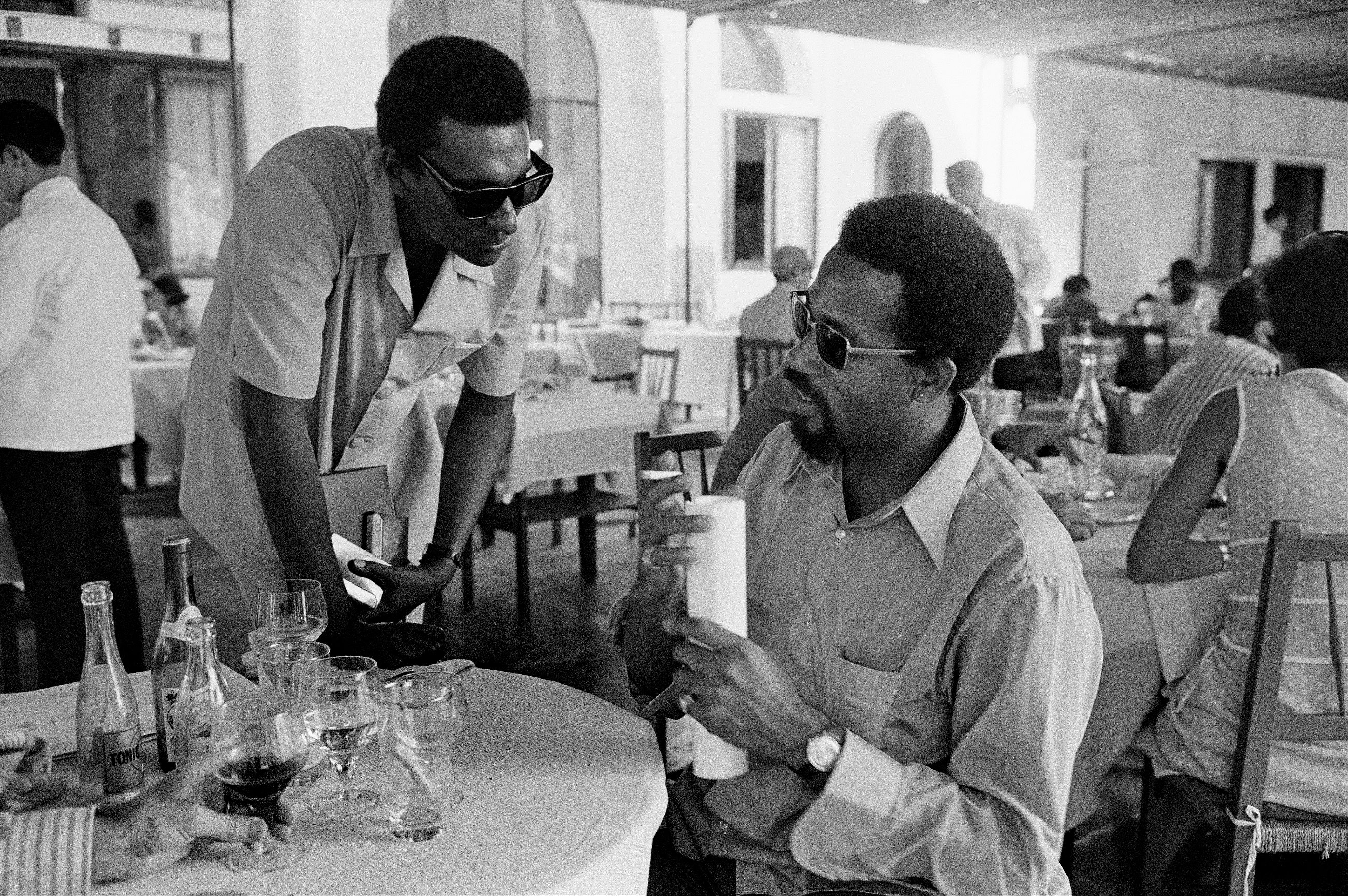

[Eldridge Cleaver with wife Kathleen in Algiers, 1969, by Bruno Barbey/Magnum]

For a brief spell in the early 1970s, global revolutionaries flocked to Algiers much in the same way that galactic freighter pilots descended on Mos Eisley. They came at the behest of Algeria’s dictatorial president, Houari Boumediene, a onetime military commander who loved to use his nation’s petroleum wealth to thumb his nose at the West—sort of an Arab Hugo Chavez, except with fewer berets and talk shows. Boumediene offered generous monthly stipends to any armed group that was dedicated to overthrowing colonial masters or otherwise “decadent” regimes. And he let those groups’ exiled leaders operate at will in Algiers, where they often set up headquarters in regal-yet-decaying villas that had once belonged to well-heeled pieds-noirs.

The insurgents who took advantage of Boumediene’s largesse came from every corner of the globe: Algerian money and hospitality flowed to fighters from Colombia, Rhodesia, North Vietnam, West Germany, and dozens of other countries where young men and women dreamed of obliterating the political status quo. Perhaps the most famous recipient of Boumediene’s generosity during this era was the Black Panther “Minister of Information” Eldridge Cleaver, who fled to Algiers in 1969 while on the run from an attempted-murder charge in California. Boumediene was taken by Cleaver’s bellicose anti-American rhetoric, which included vows to burn down the White House and oversee the nationalization of Standard Oil. He rewarded the Soul on Ice author with a $500-a-month stipend, which Cleaver used to set up what he referred to as the International Section of the Black Panther Party—a commune of sorts that attracted several other black American radicals to Algiers.

As I describe in my new book, The Skies Belong to Us, the Algiers that Cleaver and his cohorts inhabited was a comfortable place, replete with embassy cocktail parties and seaside bungalows. Sudanese-Algerian photographer Abdo Shanan tracked down a few of those locations recently, or at least, he did so as best as he could—Algeria today is still largely a closed country for photojournalism, particularly in politically sensitive areas like La Presidence. What follows is a rough guide to the places that the Panthers haunted during the few years when post-colonial Algiers was their oyster.

4 Rue Viviani This two-story villa in the tony El Biar neighborhood was once the property of the Vietcong, which had a strong presence in Algiers. When the group moved to larger digs in 1970, it donated the building to Cleaver, who had recently visited North Vietnam on a goodwill mission. (Cleaver, in return, agreed to make several broadcasts over North Vietnamese radio, in which he urged African-American soldiers to kill their commanding officers with grenades.) The villa became the International Section’s headquarters, the place where Cleaver and his beautiful wife, Kathleen, would grant interviews to curious Western journalists for up to $1,500 a pop. In August 1972, it was raided by the Algerian army after Cleaver made the grievous error of publicly demanding that President Boumediene give him the $1 million in cash that had been brought over by a group of American hijackers. That raid signaled the beginning of the end of the Panthers’ time in Algiers.

9 Rue du Traité This was the Cleavers’ family home, where Eldridge, Kathleen, and their two young children (including a baby) lived. Just down the street was the apartment of Elaine Klein, the daughter of a wealthy Connecticut dress-shop owner who had become active in the Algerian liberation movement while studying at a Parisian art school in the 1950s. She later became the press secretary for independent Algeria’s first president, Ahmed Ben Bella, whom Boumediene overthrew in a bloodless coup in 1965. (Ben Bella would spend the next quarter-century under house arrest.) Klein stayed in the new regime’s good graces, however, and she was an important liaison between the Panthers and the government.

Bab el-Oued A cozy seaside neighborhood north of the city center, where several revolutionaries chose to reside in order to take advantage of the nearby beaches. Among the residents was Donald Cox, the Black Panthers’ erstwhile Field Marshal, who was suspected to have participated in the murder of a police informant in Baltimore. (He was also famous for being a character in Tom Wolfe’s “Radical Chic,” the acidic account of a Panther fundraiser held at Leonard Bernstein’s Park Avenue duplex.) Cox resided in a bungalow which housed a short-wave radio, which he used to gather news from back home—including the first word of the $1 million hijacking that would eventually lead to the International Section’s demise.

Pointe Pescade A crescent-shaped beach much beloved by the French colonial elite, as well as the Panthers and other revolutionaries with surf-and-sand proclivities. This is where the two main characters from The Skies Belong to Us, American hijackers Roger Holder and Cathy Kerkow, spent many of their days while in Algiers.

Hotel Aletti (now Hotel Es Safir) An Art Deco edifice right on the downtown waterfront, the Aletti had the liveliest casino in all of Algiers, with baccarat tables that teemed with foreign oil executives. It was also where the Boumediene regime stashed freshly arrived revolutionaries whom it had not yet cleared for security purposes. These new guests were gently interrogated by Boumediene’s secret police in the Aletti’s comfortable rooms, then allowed to dine on lobster at the restaurant at night.

Hotel St. George (now Hotel El-Djazair) This was the equivalent of the Mos Eisley cantina in Star Wars—the place where revolutionaries mingled in a well-appointed café where the (bad) wine flowed.

La Presidence Houari Boumediene can certainly be faulted for his viciousness—he employed a team of political assassins, including the notorious “Salah Vespa,” to kill his opponents both at home and abroad. But no one will ever accuse of him not being a hands-on dictator, especially when it came to dealing with his pet revolutionaries. Before approving any stipend or asylum request, Boumediene would invite the hopefuls to visit him at the presidential palace, a pristine Moorish villa guarded by saber-wielding soldiers in long white capes. The revolutionaries would be escorted down a narrow marble hallway to Boumediene’s wood-paneled office, where the president held court beneath a gold-framed painting of praying Algerian peasants.

You can purchase “The Skies Belong to Us” here.