Mestiza de Indias is an innovative, Maya-inspired regenerative farm in the middle of a region threatened by mass tourism and overdevelopment. Its founder has a lot to say about why food matters.

Halfway between Merida and the coast in the Yucatán Peninsula, at the end of a winding dirt road through the jungle, a farm called Mestiza de Indias is trying to address some very large challenges with some seemingly small first steps. The goal: practice organic, regenerative agriculture that combines ancient Mayan knowledge and modern techniques.

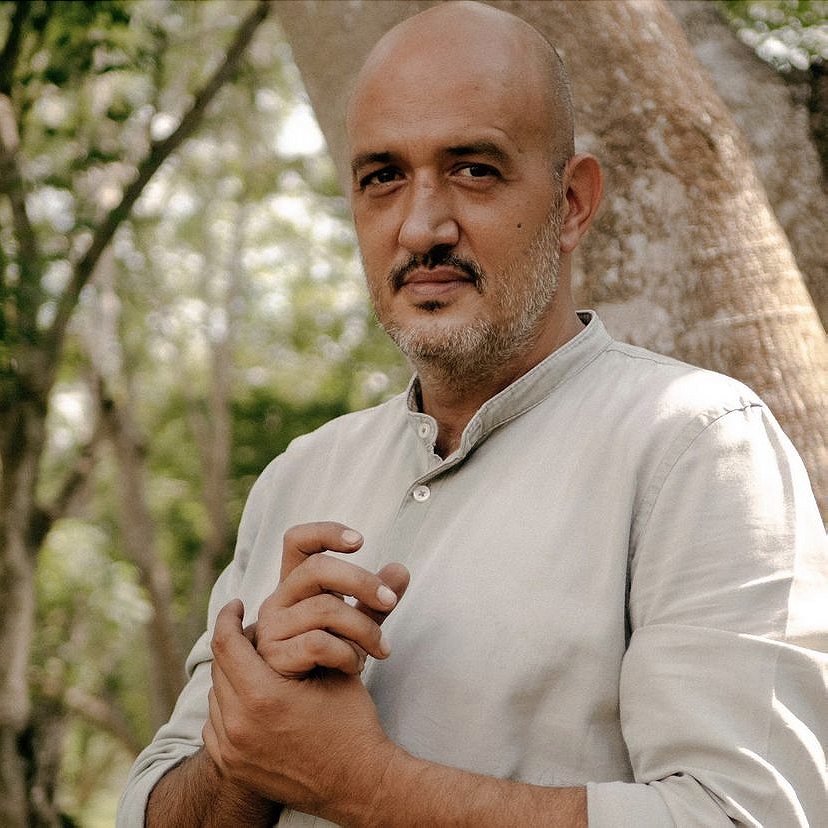

The farm, which our League of Travelers journey will be visiting this December, is the natural brainchild of this couple: a world-wandering Catalan named Gonzalo Samaranch Granados, and his Mayan wife Martha Elena Chan Tuz. Alongside a group of collaborators from their local communities, they are using their small farm outside of the town of Espita to not only grow delicious things but also to offer alternatives to indigenous economic migration and a regional economy marked by large-scale tourism fiascos and overdevelopment of the nearby Mayan Riviera.

Journalist María Elizondo spoke to Samaranch on the phone to talk about his path from Barcelona to the Yucatán, what he has learned from the Maya, and why farming their way is a political act.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Roads & Kingdoms: How did you end up in Yucatán?

Gonzalo Samaranch: Well, it’s a long story but basically after having led a very comfortable life in Barcelona and after having worked in journalism and the world of art, I felt a little disconnected living in the city.

I always thought about an experience that I had had in my twenties when I had the opportunity of living within a community in the Amazon jungle. There, I discovered other ways of being in this world, in nature, in harmony with the surroundings, and I always cherished those memories.

Some 10 years ago, I decided I no longer wanted to think about it but instead try to move forward with some project related to nature that could also have some social transcendence. I decided to start traveling the world in search of farms.

I came to Mexico a bit by chance – it wasn’t planned. I arrived in Valladolid in Yucatán one night, and when I woke up, there was a parade at Calzada de los Frailes where some children were dressed as Emiliano Zapata. I fell in love with the place instantly… It felt a little bit like Sevilla, but here there were the Maya women wearing huipiles (traditional embroidered Maya dresses). It was such a shock, I thought it must be a signal.

R&K: Did you immediately find the farm?

Samaranch: It wasn’t right away. Ten years ago, Valladolid was a small town, so I would often go to Tulum. In Tulum I got offered a job to manage a small hotel. I stayed there for a year and a half. That gave me the opportunity to understand the Riviera Maya, especially Tulum, which was then very different. It didn’t have the large corporate hotels and the development the rest of the Riviera has. People were looking then into making Tulum a sustainable area, the hotel owners were present, the places were cared for, and they had, we could say, a soul.

I thought there was an opportunity here because all the hotels had to buy produce from elsewhere since there were no local products here. And I thought Valladolid would be ideal, it’s an hour away from Tulum and the land is more fertile than at the Riviera. So, every weekend I would go searching for a place to farm, I would rent a car and after seeing tons of places I found a man on a bike who sold me his property.

R&K: And why did you choose this farm?

Samaranch: We did a lot of studying. We studied the underground water currents. The place had to have very precise characteristics for us to be able to grow and produce organically. It shouldn’t be around other farms that used foul practices. It had to be sort of isolated.

I always wanted it to be not just a space for growing organic produce, but also a space where we could practice regenerative farming. And not only farming but regeneration on other levels, on a personal level, that people could come and possibly experience a certain change through the environment.

This place had a tiendita (small convenience store) in ruins, there was a cenote nearby, that gave it the elements to create a space for agrotourism.

R&K: Did you start this project on your own?

Samaranch: I started on my own. [Eventually] I married Mara (Martha Elena Chan Tuz), who is from the local community, but that was sometime later.

R&K: Why is the project named Mestiza de Indias?

Samaranch: It’s an homage to the first mestiza (daughter of parents of different ethnicity). There’s a beautiful story about Gonzalo Guerrero, who is considered the father of mestizaje here. He’s a Spaniard who drifted at sea and ended up in the coast of Quintana Roo, he was taken prisoner by the Maya people. He learned the language and instructed the Maya in tactics to defend themselves. As a token of gratitude, he was given a Maya princess in marriage. And so the first mestiza was born.

R&K: How many people work at the farm right now?

Samaranch: Right now, we are a team of about 20 people, up to 30 during high season.

One of the things that I’ve tried to do is for the people who collaborate at Mestiza de Indias to feel that this project is also theirs. I always strive to have as many women as men working at the farm. This has also been part of the project, to move towards certain values like gender equality, for example.

R&K: And Mara, besides being a partner in the project, has she been a teacher as well?

Samaranch: Yes. We work alongside in this project, and being married to her, she has helped me to understand the Mayan cosmovision, which is very special. There is a lot of ancestral knowledge that the communities have, and it has been fundamental in building this project. Because I got here with very innovative ideas, but in the end, the people from the community are the ones who have given me the knowledge of nature. And without that knowledge this project would have been impossible.

R&K: How did the community react to you at first?

Samaranch: Well I think I must have appeared like an extraterrestrial to them because I am 6’ 2”. I felt they had a certain distance toward me, but I wouldn’t say it was rejection. I recall some laughter as well. They would laugh a bit at my ideas, that someone would want to plant anything in the middle of the jungle. Because most people look for land near the highway. And people have a certain respect, fear even, of the jungle. It’s a jungle that has its dangers: there are pumas, there’s lots of venomous snakes. But little by little we were able to establish a closer relationship.

R&K: And what was the local reaction to the project?

Samaranch: A lot of people told me it was impossible. Because the idea was that the land is not fertile, and to a certain extent that was true. I have heard of a lot of agricultural projects that have failed here, I think because people would want to apply techniques from other regions to this land. And we have here a very peculiar climate. It is a land that is young, with very few minerals, and a lot of fauna. And a lot of humidity. It’s complex.

But I also think people hadn’t observed nature. In the end what we try to do is reproduce that complexity that nature has, to apply it in agriculture. That is what regenerative agriculture is about. It’s not about planting a hectare of habaneros but about mixing and rotating crops.

R&K: How are you regenerating the soil there?

Samaranch: There are different methods. One is agroforestry, where tree planting is combined with the vegetable planting. It’s the association of crops and the rotation of crops. Because agriculture is an extracting activity, you’re extracting nutrients from the soil. So regenerative agriculture is about returning those nutrients to the soil. In traditional agriculture they do that through chemicals. We do it through biodiversity.

R&K: How many varieties have you got planted right now?

Samaranch: At a certain point we’ve had more than 100 varieties. We have been doing testing, a sort of curatorship of the land. Maybe this term is more aligned with the art world, but we have tried to save those fruits and vegetables that the industry has discarded. The industry chooses what it feeds us based not on nutritional standards or environmental benefits, but on economic benefits. For example, they choose vegetables with tough skins because they stand the boxing process and endure the lengthy transportation process. And for those types of reasons a lot of ancestral varieties have been discarded, tomatoes with thin skin and those that require immediate consumption, for example.

R&K: When you worked in Tulum, where did the produce come from?

Samaranch: From stores or distributors in other states, mainly Puebla, Querétaro, and Guanajuato. Imagine, between the trucks and the distribution centers to the hotels in Tulum we are talking about a 2-to-3-week trip. Even if the will to use organic products was there, the products couldn’t be found nearby.

R&K: How many restaurants do you supply now?

Samaranch: We started with a lot. But Tulum has been changing and so we have lost clients. Previously in Tulum the owners were very involved in the restaurant and hotel operations, but nowadays a lot of the projects are very corporate. And there’s also competition.

But I consider myself a partner of my clients, more than a purveyor. We look for an alliance with them so that we can plan together, be part of a team. Some hotels have even invested in the farm so that we could extend our planting surface, so we have a more personal and direct relationship with them than just a client-vendor one. But it’s not the majority.

We’ve had difficulties because of greenwashing in the area. There’s a lot of bad practices going on, where hotels are selling products as organic and that’s just not true. They’re offering their customers cheap products and branding them as luxuries.

R&K: I assume people just won’t notice the huge flavor difference between good produce and bad.

Samaranch: Yes, it has to do with the quality of the soil. And industrial systems… what they do is put into the vegetable the minimum required, just enough so that it grows. For example, now there’s a trend for hydroponic vegetables, but with that method they inject 4-5 nutrients into the water. It grows and looks pretty but the taste can’t be compared to that of a vegetable grown in a rich soil. Because in the end the flavor is a result of the diversity of minerals found in the soil. The industry wants volume. We’ve lost the artisanal character of agriculture.

Mestiza de Indias is also for that. We want people to come and visit us, and to try things straight off the soil, carrots that taste a bit like the soil, tomatoes from the vine. Because it’s a part of an experience to create consciousness around the topic.

if you’re going to eat the same things you eat in New York or Paris, then why travel?

R&K: Can people stay over at Mestiza de Indias?

Samaranch: Not currently, no. But that’s the direction we’re headed at. We’re building what’s needed to be able to host. Because we receive a lot of calls from people asking, not just to visit and stay, but of people who want to stay and work, volunteer, but we’re still working on that.

We don’t have an investor group behind us, everything has come from the sale of vegetables. I arrived in Mexico with the money to be able to buy the land, but everything else has always come from the sale of fruits and vegetables. We’ve grown slowly, little by little.

R&K: I’ve heard that you have several phases planned, with phase 1 being what you already do, the farming. What can you tell us about phase 2?

Samaranch: Here it is a little bit like in the Nordic countries but the other way around. There, you have 3-4 months agriculture and then it snows. Here we have the same but with heat and rain. We have a few months of production but then the conditions are very harsh. So, phase 2 is about preserving. So that we can offer products during the season where we can’t plant much.

In that phase, we could also include more people from the community, especially women, because that’s another important issue around here: communities are made up basically of women, because the men go to the Riviera to work, and they sometimes don’t come back until after a couple of weeks. There’s a lot of women alone, with children, jobless, moneyless, so that was also the idea. That they would be able to generate their own income and have Mestiza de Indias act like a commercial partner. Because in the end the problem that entrepreneurs have is that they don’t have access to the marketplace. And so we can be that link, through fair trade.

We are planning on starting that phase this year. I have found the people that can lead the project because I need help. I used to do everything with Mara, but now she’s become Espita’s Director of Tourism, so she’s been very busy. [Espita has been recently named a Pueblo Mágico—a denomination given by the Mexican government to towns that preserve cultural heritage].

R&K: And phase 3 would be agrotourism?

Samaranch: Yes, and the idea of receiving people who want to come to learn. Because that’s another thing, the formative part. I think we should also focus on education. I can tell you that one of my biggest satisfactions with this project has been when the daughters of Doña Teresa or Doña Lourdes, ask: “are the eggplants ready?” “Are the tomatoes ready?” “Are the carrots ready?”

To have kids asking for a vegetable, that’s a feat.

Sadly, a lot of people in the communities are sick. When the men go to the Riviera to work, they are not working the milpa (a home vegetable parcel that is the traditional system of agriculture). And the milpa was the only way to obtain fresh, healthy food in the communities. Men bring money, but with money you can’t buy good food. With money you can buy food that’s sold at tienditas: potato chips, some tinned foods, Coca-Cola. And people are sick. So, to have the power to improve diets, that’s what gives me the most satisfaction.

R&K: And I imagine the men, if they’re working at the hotels, must be eating the sort of thing that the tourists ask for, removed from nutrition and tradition?

Samaranch: That’s something I hear a lot from chefs: “We have to give the client what they want”. I think it’s a great error, because we are generating a type of tourism that is totally homogeneous. You know, if you’re going to eat the same things you eat in New York or in Paris, well why travel?

To travel is precisely to be able to live new experiences. And taste and gastronomy are one of life’s greatest experiences. In this region there’s some amazing fruit. And in the hotels, you end up eating strawberry and kiwi. What’s the point of that?

And we’re talking about a health issue here, too. The scientific evidence is there that most illnesses people get are related to food.

But people keep eating as if it were part of a show business. And the chefs outdoing themselves to see who is more creative, we forget that in the end food is nourishment, one of the most important things we do daily and that conditions our life in the future.

You know you’re not going to die from eating an agrochemical with dinner, but the colon cancers we see worldwide are just that. I think we’ve disconnected. To have industrialized food, to have industrialized all facets of our life, has made us disconnect from what we eat.

Who is giving food to us? Where is it coming from? I always say food is a political act. Because the decision to consume certain things over others, well that’s more important than voting every six years.

You can be a part of an unjust system. Or you can stop and say: no, I don’t want to be promoting this system, and you can do that by questioning and deciding what you eat and where it comes from.

Another thing we do at the farm involves cooking some rescued pre-Hispanic dishes. Recipes that people can no longer taste if they’re not invited to a traditional Maya family home. And tourists here, well, they don’t go to a traditional home to eat.

There’s a lot of recipes, a lot of them vegan, that are really interesting. We make them here, we start from scratch and show people how they’re done. Like for example Kots’ob, which is a typical dish from this region, it’s like a corn tamal with pumpkin seeds, hoja santa, chile, spring onions, it’s very popular, people love it.

R&K: Are these recipes written somewhere?

Samaranch: No. They’re at the homes, in the families. This is what people eat traditionally.

But whoever has a milpa, they can still eat these foods. It’s not that common. But there are still families that live in an ancestral fashion, they live in a huano palm house, they work the milpa, they have a solar Maya in their patios.

This is one of the things that fascinates me: Two of the world’s most innovative food production systems were invented in Mexico.

The chinampas that were able to feed a city, and the solar Maya, where each family is responsible for feeding itself.

In a solar Maya, in the back patio there’s Ka’anche’, which are elevated platforms or beds in which to put the food so that the animals beneath can’t eat them. Then they have the fruit trees, and then the milpa, which is a very diverse thing.

In a solar Maya each family was responsible for feeding itself. Nowadays these solares are full of plastics and trash from the tienda. But suddenly you find a family that is still upkeeping their solar. To find something so ancestral, it’s a treasure.

You can be a part of an unjust system, or you can stop and say no.

R&K: And what about alcohol or spirits? What’s traditional here?

Samaranch: Usually Xtabentún (made from honey) is the local spirit. But there’s a lot of good things being made around here, there’s some people that are making good kombucha with tropical fruits that are incredible. And there’s good artisanal beer being made right now in Yucatan.

And there’s also the prehispanic drinks that are not alcoholic, made from corn, like pozol, which is a typical drink made of corn in Yucatan. The farmers would take with them a little ball of corn masa, and they would mix it with water and some honey.

And we also make a lot of juices and waters with fruit from the farm: guanabana, saramullo, anona, yaca, zapote negro, bonete.

R&K: Now that the League of Travelers will be travelling to Yucatán, and spending a night in Espita and time at Mestiza de Indias, what plans do you have for them? Are you going to cook?

Samaranch: Yes. We are planning on showing all the processes that we do here at Mestiza de Indias. Walking the fields to have people try vegetables that you just pulled from the earth. There are some varieties that I don’t think many people have seen in their lives: African cucumbers, Japanese eggplants…

We want to show them that curatorship that we have been making and we have been talking about. And people really are fascinated by these varieties because they don’t know about them. We have so many varieties of tomato, we have ones that weigh a kilo, they’re called Tomate Piña – Pineapple Tomato, which are a type of heirloom. We have marbled tomatoes. We have over 20 varieties. And after seeing the crops, it’s possible that we do a baño de monte which is inspired by Japanese walks in nature. It’s a very special moment because the jungle is very special. It’s a sanctuary for flora and fauna where we are. We have even seen monkeys.

And then once we return, the women are going to tortear -hand make tortillas of ancestral corn. And we’ll make some vegetarian dishes, like eggplant tacos with garlic flower, something that is very simple but delicious.

Samaranch: And for those who do eat meat, we make our own version of Cochinita Pibil, which we make with a pineapple that we grow here and is cooked slowly for 24 hours. You know the Pib? You build a fire with stones that keep the heat that stays at low temperature during a long time. Everything turns out delicious.

The League of Travelers—Roads & Kingdoms’ new travel project for readers and other likeminded wanderers—is returning to Mérida from December 2-December 6, 2023. See trip itinerary for more details, including how to join.