In 1974, a Dutch photographer set out to capture what the Netherlands really looked like, beyond windmills and tulips. Forty-three years later, photographer Cleo Wächter retraces the project to see what’s changed.

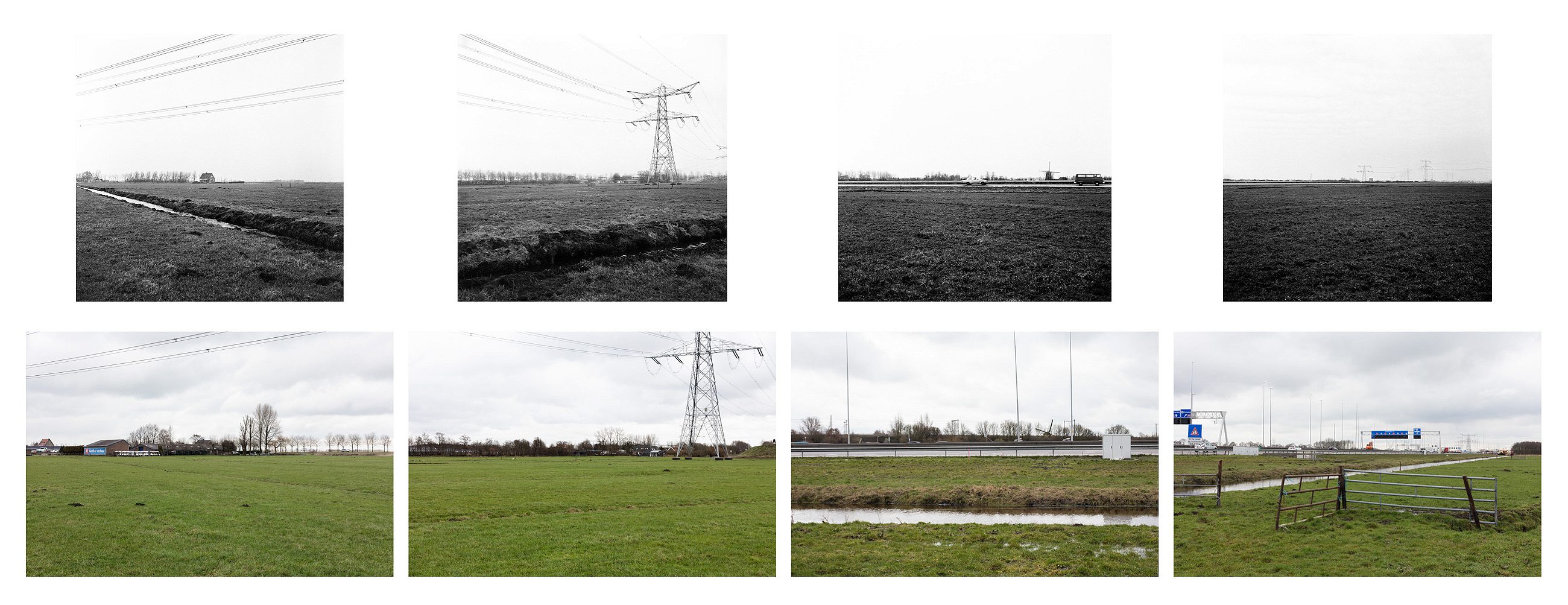

Windmills, wooden clogs, neatly arranged tulips: These might be a foreigner’s idea of the Netherlands. But these tropes don’t just appear on airport postcards. They’re also common in paintings of Dutch landscapes—a fact that fascinated photographer Reinjan Mulder. As 26-year-old Dutch photographer Cleo Wächter explains, Mulder was interested in the way landscape paintings were rich in clichéd images. “In the Netherlands, that often meant windmills, cows, a small road leading to the horizon,” says Wächter. “So Mulder said, ‘This is not what the Netherlands looks like.’” So, in the early 1970s, Mulder traveled the country, mapping locations on a grid and photographing the north, south, east, and west of 52 places to show what the landscape of the country really looked like. The project, Objective Netherlands, received little attention—until Amsterdam’s renowned Rijksmueum stumbled upon it decades later, and exhibited it in 2016.

Wächter’s own photography—such as her Royal Academy of Art graduation project, Anthropocene: Mapping the New Geology of The Netherlands, and Autostop, in which she retraces her father’s hitchhiking route through Scandinavia—is preoccupied with landscapes. Just one year out of school, her work caught the eye of landscape architect Berno Strootman, the Dutch government’s Chief Advisor on the Built and Rural Environment, who had seen Mulder’s original Objective Netherlands at the Rijksmuseum. Strootman commissioned Wächter to update Mulder’s original project, following in his footsteps to show what had changed in the Netherlands’ landscape in 43 years. It became, as Wächter puts it, “a conversation between two moments in time.” R&K’s Emily Marinoff spoke with Wächter about the challenges of recreating Mulder’s project, how the Netherlands has changed, and how landscape photography can be political.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Emily Marinoff: How did you get into environmental photography?

Cleo Wächter: It was always a hobby of mine, but I never really considered studying it because I thought I should pick a more academic topic. Since I was a child, I’ve loved astronomy, geology, and archeology, and I always enjoyed exploring these topics through photography. In the first year at the Royal Academy you’re just experimenting a lot. You take classes in different kinds of photography, like fashion, advertising, journalism, and documentary. I liked documentary photography best because it’s a way to make research visible and approachable.

Even though I photograph landscapes, it’s always about people.

Somewhere in the second year of my studies, I became more drawn to landscapes. I felt that landscapes often tell more about people than portraits do, because portraits only tell you about the relationship subjects have to the photographer. I liked looking at landscapes more, because I think you can read a lot from them while inviting the viewer to place themselves into it. Even though I photograph landscapes, it’s always about people.

Marinoff: How long had you been out of school when you got assigned to do Objective Netherlands?

Wächter: Just one year. And it fit quite nicely with the things I’d done before. I graduated with a project called Mapping the New Geology of The Netherlands, in which I went to all these places in The Netherlands where you could see that the landscape was physically altered in an irreversible way. The year after I graduated, I did Autostop, in which I hitchhiked the same way as my father hitchhiked in 1980. I think those two projects caught the attention of the government adviser for physical living environment in The Netherlands, who had seen the original Objective Netherlands exhibited in the Rijksmuseum, and thought it was a good idea to do it again.

I remember getting the phone call, and hearing the concept for the first time. I thought “Oh, I wish I had come up with this idea myself.” They asked me, “Are you willing to travel all across the Netherlands?” And I said, “Yes, that sounds great.” And then it all happened pretty quickly. I met everyone the next week, including the original photographer, Reinjan Mulder. He had been asked to recreate the project, but he just turned 70 this year and said, “I’m not in the best shape to do this.” But he had the idea to have a young photographer take the project on, so that in 40 years we can pass it on to someone else again, and they’ll carry out the tradition of reflecting on the Dutch landscape.

Marinoff: So were you able to talk to the Mulder about his original method to figure out how to approach it in your own way?

Wächter: He was very much involved. I feel like he’s in the prime of his life and he was always sending out ideas. Reinjan was part of this time in photography and art history when people still thought it was possible to be objective, but I just don’t think it’s very interesting to try to be objective anymore. In a way, it became a conversation between the two moments of time, 1974 and 2017. In 1974, Reinjan thought he was doing something completely new. For me, it would be strange to photograph the landscape in black and white. If you want to say something about that landscape, I think it has to be in color. I wanted to show it by using techniques [from] my own time to emphasize that he was also very much part of his own time.

Marinoff: When you went to each place, what was your approach to taking these photographs?

Wächter: I’m sure many photographers have probably told you that being a photographer is 10% taking pictures and 90% office work and calculating. We started with two months of finding the old maps that he had so that I would know what I was getting myself into. And whether I would need permission, or need a boat, or need anything [to access the sites], so that was a whole process that went on before organizing the places. Google Maps very much came in handy. And I would do two to three places a day, and I would go there, and often. So you have to pretty much have a good sense of the coordinates, you have a pretty good sense of the radius, and you find yourself in the middle of a field and will take an hour to just take one step back, one step forward, so it shifts a little bit.

Because that was the difference between Reinjan and I. He did it with a compass. He just took north, south, east, west. And he had to picture a spot on the map, and I have to give him credit, he was really precise, but I had to make a replica of his picture in some way. Where he’d maybe spend ten seconds making the photos, I’d spend often over an hour making sure that it was in exactly the same spot and done right. And of course, we’re bringing the old map and the new map, the compass, and old photos, which I also divided intp a grid so I could compare them if I had to. So, it was really challenging.

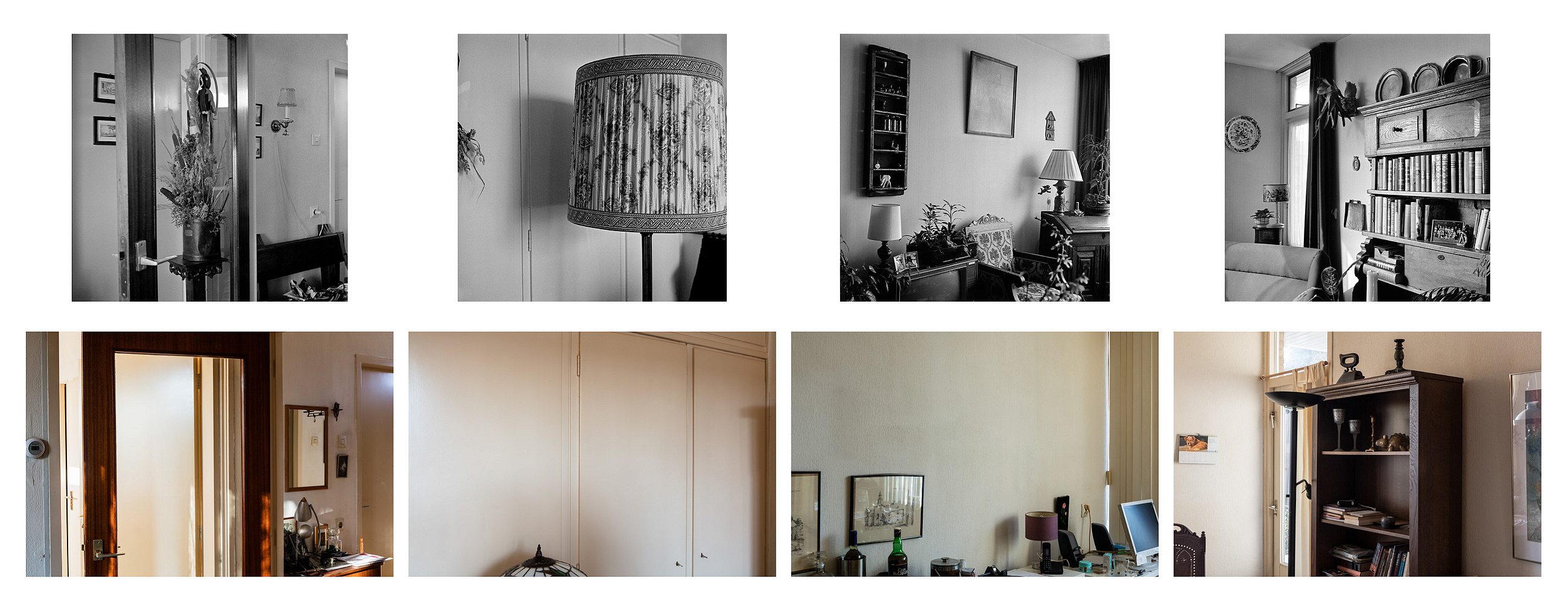

Marinoff: There was one location I wanted to ask about. I think it’s Velp, number 45, that looked like it was in someone’s house?

Wächter: It is in someone’s house.

Marinoff: What was the story there? It’s the outlier of all of the places that you photographed. What had changed?

Wächter: There were different people living there. They didn’t know the former owners. I think the people living there now have lived there for 12 years. It took a bit of persuasion, be honest. But in the end, it was all fine. I really like that in the project you can see how precise it was. It doesn’t matter if he’s right in front of the wall, or in someone’s house. The map says he has to take a picture there. But what I like about that place is that if you look at the interior, you can also see that in the place where there used to be a lamp, there’s still a lamp, but it’s a different lamp. And the place where there used to be a big plate on the wall, there’s now a big calendar, or the writing that’s there, there’s now a computer. It says a lot about the way the room is inviting people to decorate it. So it’s still being used in the same way, but in a different time.

That actually wasn’t the most difficult place I had to get into. There was another place that I really had to go back three times. Because the project was partially funded by this part of the government, I also had a letter with me from the Minister of Culture, which explained the project and what we were doing. And most of the time I didn’t even have to use it. In a way I actually didn’t want to use it, because it may work against me, as in maybe people would think it was too official. Then I’d have to say, “I have these old photos,” and that was what interested them the most.

We made a deliberate choice not to show the exact coordinates on the website, because I was a little bit afraid that people would search for the place themselves, which actually has happened. It’s also a regional project, and sometimes we’d receive photos of people who had gone to these places and would say, “Oh, and now it’s like this.” I think it was a natural evolution that people wanted to see all the places that changed.

Marinoff: Have you seen how this has had an effect on how people view the Netherlands, whether they’re Dutch or not?

Wächter: What’s really interesting about the project to me is how many different layers it has. So, first there’s this whole philosophical concept of Reinjan Mulder trying to say something about art history and the way we view the world. And then because of the time that went by, I think to me it makes sense that it was exhibited 40 years later, because by then it had become this historical document. Then I came and added my story, which also answered the question the people commissioned me had: What has changed? And it was a critical question toward landscape, because we’ve become more aware of what we’re currently losing. Biodiversity has gone down a lot everywhere in the world.

I think [the project] makes its invites you to reflect on it. It’s not giving you all these answers, but it invites you to reflect on it.

I’m never interested in something that’s just purely about aesthetics. It always has to say something.

Marinoff: Did this project change your view on the Netherlands at all, and how humans should interact with the environment there?

Wächter: It taught me to think beyond the cities, and gave me a more democratic view of the Netherlands. I feel like the weight of the Netherlands is often concentrated on the cities, and when you look at the news, it’s always about that. And we forget that such a high percentage of Netherland is farmland and potato fields, and a lot of water and mud. I was already interested in how we approach the environment, and [hopeful that] the nature we have in the Netherlands will be protected.

Henk Baas [head of the landscape at the Cultural Heritage Agency of the Netherlands] wrote an essay in the book [“Objective Netherlands: Changing Landscapes 1974 – 2018”] in which he says that he thinks the biggest problem when it comes to changing the landscape is that it’s not the landscape changing, but that the cultural values attached to landscapes are changing. I think that’s more of the problem. But I would say that it’s still a positive thing, because it used to be this wasteland. So, I don’t think that it has to be preserved necessarily, but the meaning of the landscape has to be perfected, or we have to be mindful about it.

Marinoff: That’s what I liked about the location that’s in someone’s home. Like you mentioned earlier, even if there are no people present in the photo, photography is always about how we’re interacting with things and how people are involved. I think even though there are so many pictures that are just the ocean or fields, [the ones with houses] make you think about how people manipulate the environment. And we’re all responsible for what’s happening now, for better or for worse.

Wächter: Yes. It’s nice that you see that. Well, to circle back to the book, because that’s the final project, I’m very happy that we got to make that, because it’s a collection of pictures just as much as a collection of essays, which really point out all of those different things I mentioned. There’s also a journalist who writes a lot about photography who wrote a beautiful essay on nostalgia. Because you can see the photos are quite nostalgic, and probably in about 40 years people will look at my pictures with nostalgia. There’s this element of monitoring the landscape.

Marinoff: Do you hope to eventually use your photography as a tool to spread awareness about what’s happening in the environment?

Wächter: Yes. I’ve reflected on that a lot lately, because when I graduated with this landscaping project, which I have now become a lot more critical about already—it was almost four years ago. I remember saying ‘no’ when I was asked whether I saw myself as an activist. I said no, because [an activist] is someone loud who spreads their opinion, and I just want to plant the seed in peoples’ minds. But I do find myself becoming less and less afraid that my work could be [seen as] political, because I started to realize that I’m always political, so I might as well use it and accomplish something. I’m never interested in something that’s just purely about aesthetics. It always has to say something.