The livelihood of Turkey’s small-scale fishermen is under threat from many fronts—the country’s currency crisis is just the latest.

Turkey, surrounded by the Mediterranean, the Aegean, the Sea of Marmara, and the Black Sea, has for centuries been a rich fishing ground—but its waters have become increasingly bare.

In the last few decades, Turkish fish stocks and production have steeply declined. Population growth and swelling numbers of fishing boats, overfishing, pollution, poor environmental regulation, and increased traffic in the Bosphorus Strait have contributed to a decline in quantity and quality of marine life. At the same time, aquaculture, or fish farming, has boomed. In 2016, Turkey was the largest producer of farmed sea bass in the world and the largest exporter of sea bass products globally.

The decline in Turkey’s fish stocks has hit small-scale fishing businesses hard, and their problems have been compounded by Turkey’s 2018 currency and debt crisis.

The lira crisis has multiple causes, among them President Erdoğan’s interest-rate policies, Turkey’s large current account deficit, its heavy borrowing to profit from its construction boom, and a dispute with the U.S. over an American pastor jailed in Turkey that resulted in sanctions and doubled tariffs on steel and aluminum. Last year, the Turkish lira plunged to almost 40 percent of its value in relation to the dollar, the inflation rate hit 20 percent, and fuel and gas costs rose sharply—just the latest in a long list of challenges for those trying to make a living on the water.

In the Bostanci neighborhood, set on the Sea of Marmara on the Anatolian side of Istanbul, I meet former fisherman Kenan Kedikli, 63, an activist, author, and head of a Bostanci fishing union. Kedikli explains that while there are many causes for the dwindling number of fish and fish species in Turkish waters and the strain on fishermen’s livelihoods, the lira crisis has been particularly damaging for small businesses—not least in his own community.

“Thanks to rising fuel costs, many fishermen had to sit out the last fishing season,” he says. (The season runs from September to April; the Turkish government banned fishing in the summer when fish reproduce in an attempt to replenish fish stocks.)

“Some families have even had to sell their boats,“ adds Kedikli. “They can’t afford to take them out every day and risk not catching enough fish to cover the cost of the fuel.”

At the dock in Maltepe, a suburb on the Sea of Marmara between the Kadıköy and Pendik districts, Kedikli and I meet up with an old friend of his, Ufuk Bağkiran, and Ufuk’s son, Sinan, as they return from a day on the water. They show us the day’s catch: two seabass. They invite us to their home nearby, where Bağkiran’s wife, Nurcan, welcomes us with çay—Turkish tea. Figurines of fishermen, shells, and boats line their kitchen cabinet. “This is a third-generation fishing family,” says Sinan. “We have fish genes in our blood.”

“We used to fish every day, to make a living, but now with the additional fuel costs, fishing has become too much of a gamble for small businesses like ours,” says Bağkiran. “We just afford to do it anymore.” Bağkiran also blames the depleted numbers of fish on years of overfishing and pollution. “The rise of civilian and military vessels passing through the Bosphorus did the rest,” he adds.

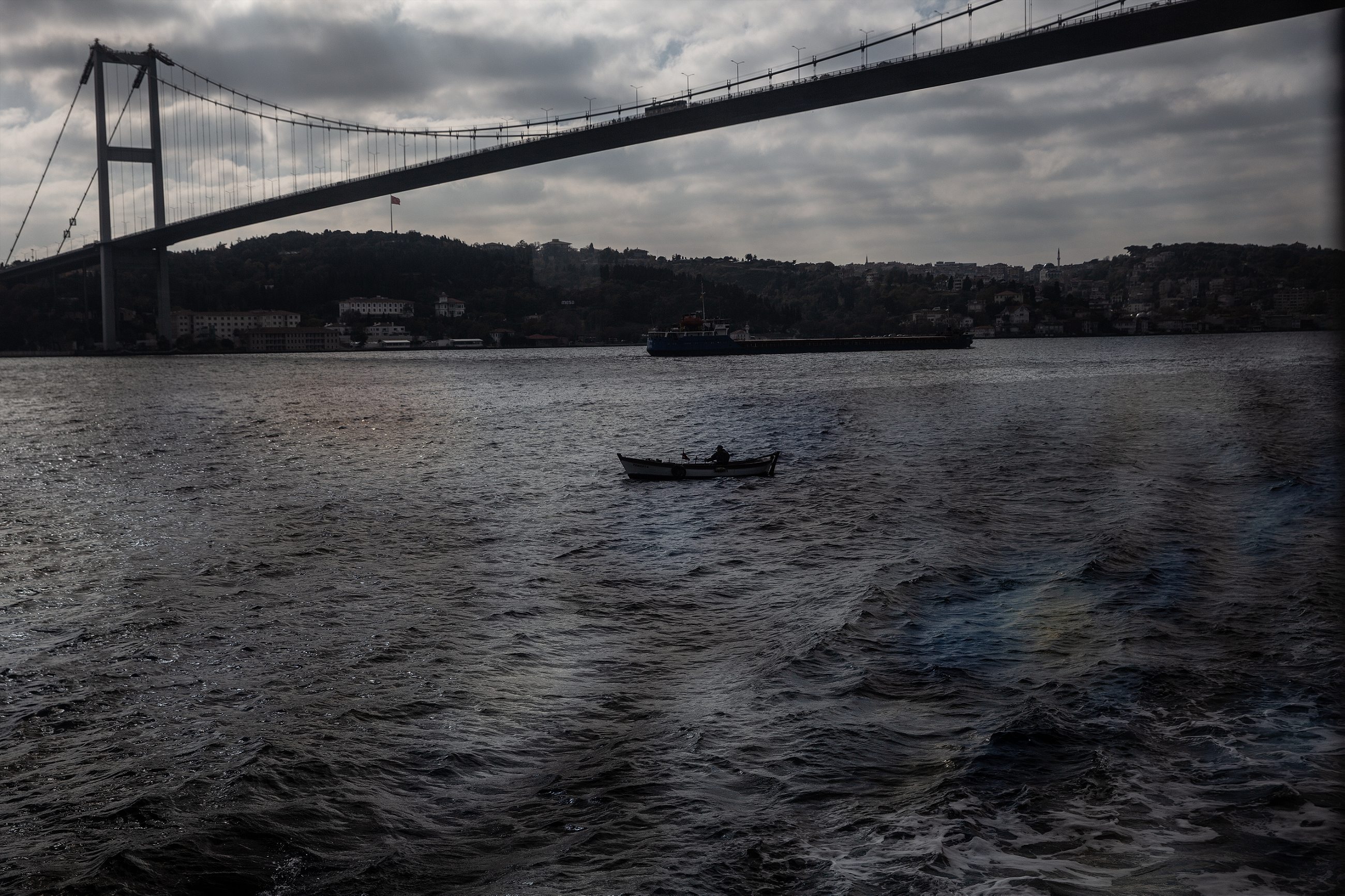

Around 127 vessels pass daily through the Bosphorus, one of the world’s busiest waterways and the only passage between the Black Sea and the Sea of Marmara. These vessels, which include passenger ferries and tankers, often carry oil, gas, nuclear waste, and highly flammable chemicals, and there have been frequent accidents. Ufuk and Sinan now work part-time for a ferry operator in the Bosphorus Strait as they try to keep the family business running.

It’s not just the Bosphorus that has become polluted. The Sea of Marmara, which connects the Mediterranean and Black Seas, is a vital passage for migrating fish species. At the marina in Tuzla, a suburb 28 miles from Istanbul on the Sea of Marmara, I meet Celal Tülü, who has been head of S.S. Tuzla SU Ürünleri Kooperatifi, the local fishing union, for 11 years. He says that destructive or illegal fishing practices, such as bottom-trawling or purse seine fishing (using large, weighted nets to scoop up schools of dense fish such as tuna and mackerel) by larger, industrial fishing vessels have gone unreported and unpunished, and have had a huge impact on the number of fish—leaving little behind for small and medium-sized vessels to catch.

According to Aylin Ulman, a researcher with the University of British Columbia’s Sea Around Us Project, the number of commercial species in Turkey’s waters dropped from more than 30 in the 1960s to just five or six by 2010.

At 5 a.m. at the pier in Tuzla marina, I board a fishing vessel for the day, with four crew. The captain, Kemal Dalyan, says they will attempt four catches. Azem Aydoğan, the cook, prepares çay. Vedat, the oldest, and Sezer, the youngest of the crew, drink theirs on the stern as they smoke their first cigarette of the day. “Some species have almost disappeared,” says Kemal. “Today, we catch mostly shrimp.”

Dalyan and his crew make their first catch after two hours: shrimp, which they sort according to size. Small shrimp can fetch around six liras per kilograms—just over US$1. “Fish have even less value,” says Aydoğan. “When we catch them, we throw them back. Food for birds.” He throws over the side as grateful seagulls hover around the boat. The rest of the day passes in much the same way. Between catches, Aydoğan prepares meals of fresh shrimp and beans. Once back at the harbor, the boxes are offloaded and loaded into a van, ready to be shipped.

Early in the morning at Gürpinar fish bazaar, the new fish-trade hub on Istanbul’s European side, fishermen, auctioneers, wholesalers, and restaurant owners all hunt for a good deal. For Turkish fish-trading companies and fish-farming operations, the sinking value of the lira—and the resulting cheaper prices and competition—has boosted fish exports to neighboring countries and the European Union, and thus, their profits. But for locals and fishermen, good deals have become harder to find.