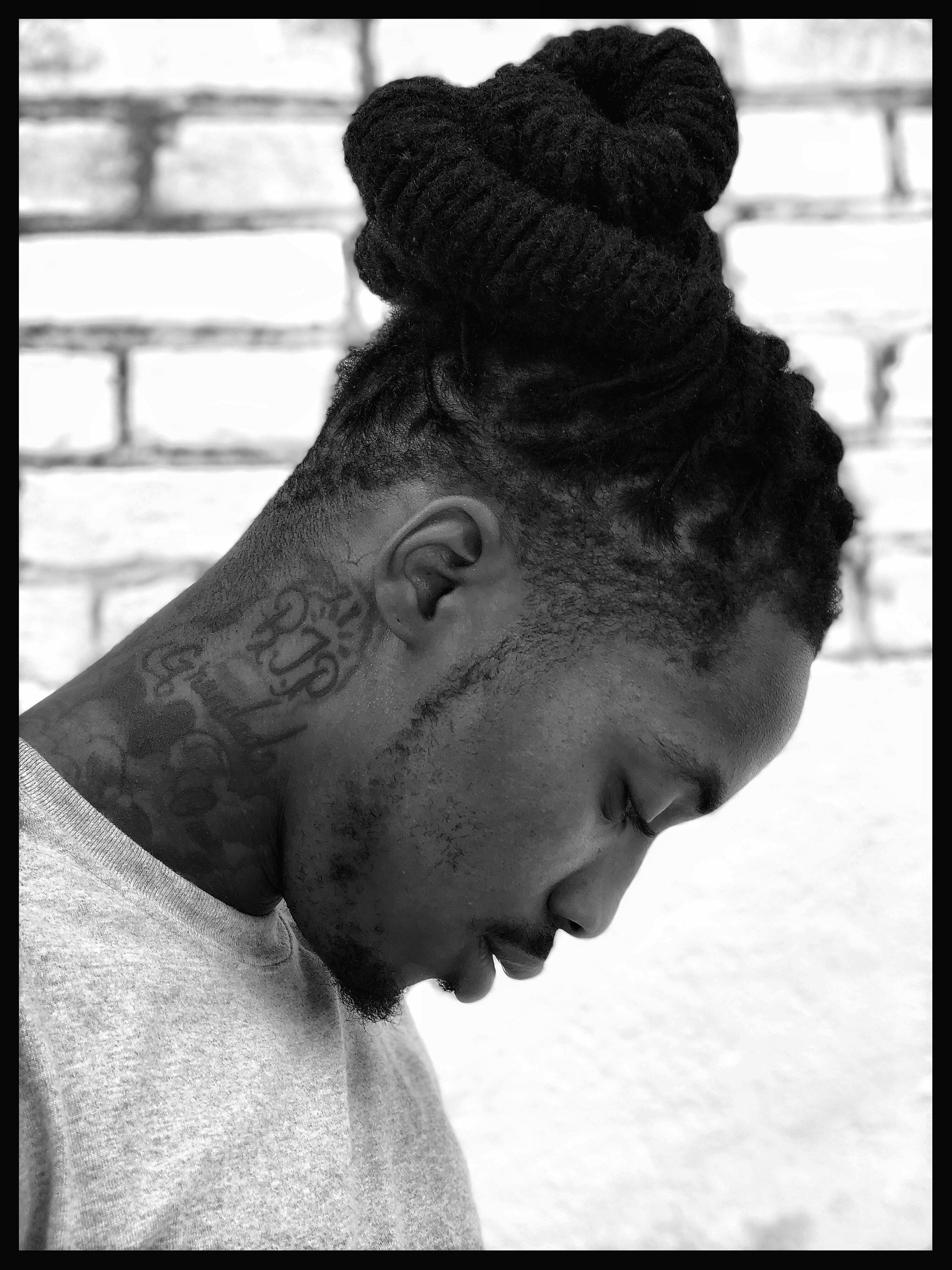

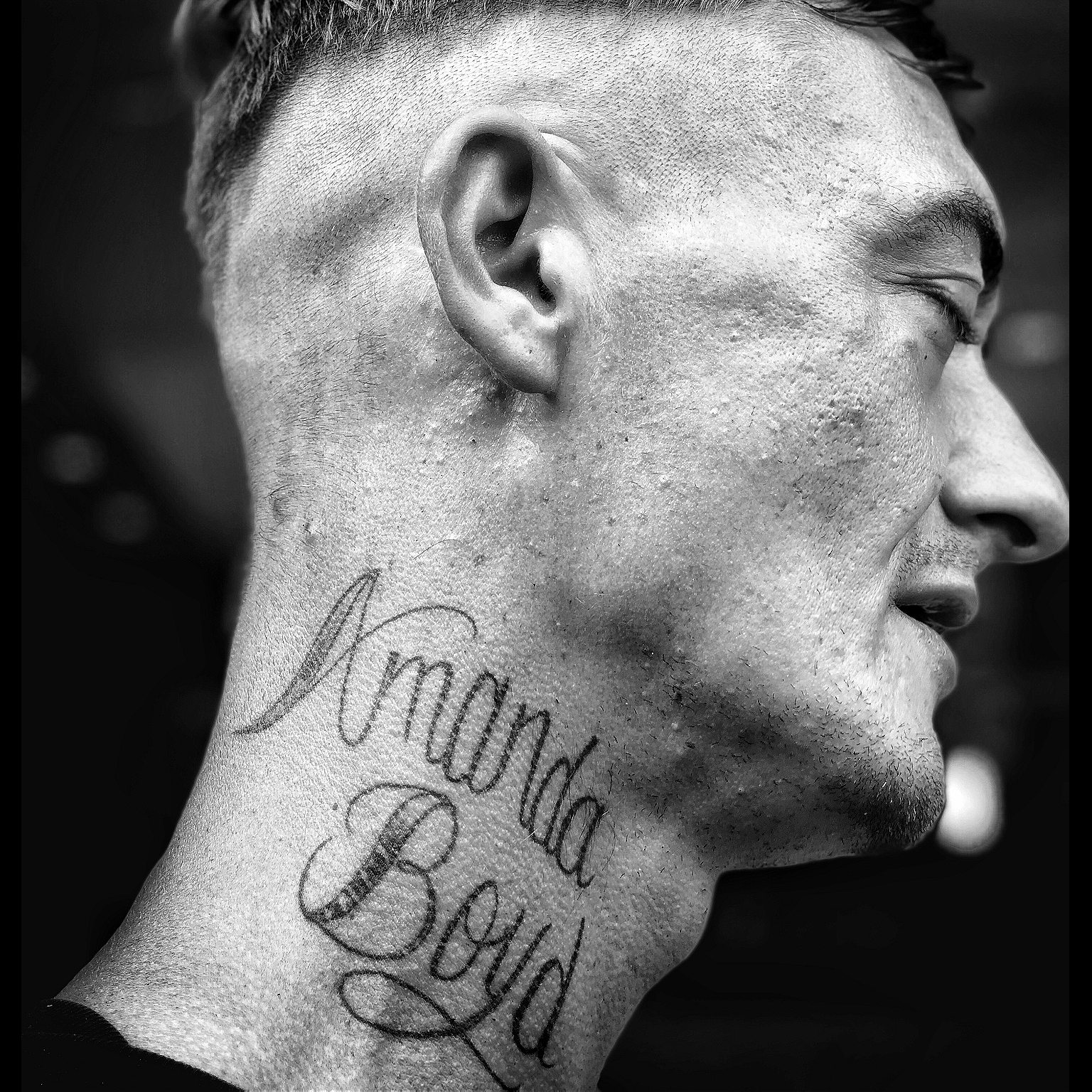

Ashley Tillery creates intimate portraiture with her phone on the streets of D.C.

D.C.-based Ashley Tillery is a self-taught photographer who works as a health and safety officer. Her early morning shifts enforcing Occupational Safety and Health Administration standards allow her free afternoons to spend photographing on the street. Tillery’s Instagram feed is a mix of intimate street life and portraiture. Her ability to connect with her subject and take time with her photos is apparent in the work. “Start with a human connection and a conversation and then slowly take out your camera,” Tillery says of how she works. “It makes for better, more honest moments, especially for portraiture.”

Tillery only uses her smartphone, which she says is an advantage for street photography, because it’s unassuming. Her background working on poverty issues in AmeriCorps and on folklore in Alabama is what initially led her to photography, a passion that grew after moving to D.C. Tillery talked with Roads & Kingdoms over the phone.

Roads & Kingdoms: What about photographing in D.C. is special to you?

Ashley Tillery: I’m black. My parents are black, but it’s a very specific type of black. It is a middle class, the upper-middle-class blackness. It’s very hoisted and it falls into a Huxtable sort of category and all my friends were the same way. My experience of blackness growing up was being around other doctors and lawyers and engineers, and it wasn’t until I got down south that I realized that there are so many ways to be black. My parents and their friends were a single thread, but it’s a tapestry. Rural blackness is very different than urban blackness. I think what makes D.C. special to me is that it is such a black city, but it’s a black city of transition. Thirty years ago, D.C. was more than 70% black, but with gentrification and other changes that number is a little less than 30% now. It’s gone from a chocolate city to a mocha city.

R&K: How is that changing the city’s culture?

AT: Well, it’s a disappearing, yet still vibrant, culture. The urban culture is still present, but the people who made the culture are disappearing. I think I likened it to a death mask; the image is there, but the life that made it is gone. That is sort of fascinating to me, especially when you talk about hip-hop or urban style. Once upon a time, if you said urban, it was almost like a racist code word. But now, in some ways, that moniker is like the death mask.

The impression is still there but the life is gone, the people who made that culture are rapidly disappearing. It’s almost like Marty McFly’s family in Back to The Future. Every time he looked at that picture, one more of them was gone. That’s kind of how I look at D.C. and I think that’s why I’m fascinated with it.

R&K: Do you feel like you are using photography to help document that?

AT: I do have a passion for making sure that the memory continues to exist not just as stories, but irrefutable photographic evidence that, yes, once upon a time, D.C. was a black city. Because right now that history is reduced to signs that nobody reads on running trails in neighborhoods that black people don’t even live in anymore. I’m actually on U Street right now. It used to be called Black Broadway but now only two of the original black businesses are left and the neighborhood’s completely changed.

You run into people who grew up here in the ’60s and the ’50s, but now they feel out of place in areas that used to be theirs fundamentally. That’s weird and it’s tragic.

R&K: How do you typically engage with subjects?

AT: In a combination of ways, but I think better images definitely start with a conversation. I’ve noticed that when you walk over and just start a friendly conversation [the subject] becomes disarmed. I have other moments when there really isn’t a conversation until after the fact. Sometimes those moments can start out very confrontational, but I stand my ground and talk to the person and then eventually they ask to see the photo. They are usually like, “I can take a better picture than that.” And then the moment just sort of grows from there.

R&K: Do you feel like there’s an ethical component to that?

AT: Absolutely. Photography is a moment in time and the photographer is telling the stories that they want to tell. It sometimes robs people of their agency to present their best selves. Whenever there’s an opportunity to make sure that people have that agency, then I like to do that. In that sense it’s not my photograph, it’s our photograph but beyond that, it’s their photograph. I just happen to be the person with the ability to capture that image.

R&K: Was there a moment when you started putting more effort into photography?

AT: When I moved from the south to D.C., I was looking for something familiar and the most familiar thing for me was taking pictures. I knew I didn’t just want to go to work and go home or to another happy hour. Especially with my background in folklore and anthropology, it was a natural interest of mine and grounded me in this new space.

I also started posting on Instagram frequently and communicating a lot with other photographers. One of them was a man who goes by the name Tasty.Chips. I reached out to him because I really loved his work, and I asked him how he made his pictures. He said, “I try to go out as often as possible and take 100 shots.” One hundred shots seems a bit ambitious to me at the time but the point was if you’re going to be a street photographer, you have to be in the street and you have to hone your craft. I didn’t start out to be a street photographer, but it has helped reinforce the fact that I really love people. I really love the energy of places and cultures, which feeds back into my folklore anthropology background. It was kind of a natural fit, and that’s why I started posting so often and taking so many pictures. In some ways, it became a meditative practice.

I was looking for something familiar and the most familiar thing for me was taking pictures

R&K: Why do you use Instagram so much?

AT: I use Instagram because I’m a self-taught amateur photographer. It isn’t like I’m going to go out there and have a gallery or that I’m saving images for a book. Instagram, especially for somebody who has a point of view that they want to share, is actually a very democratizing medium. You don’t need a gallery or a LensCulture contest or anything else to affirm you. You get to self-publish your perspective. In that sense—especially with cell phones—I feel like photography is sort of coming back to its roots. I think photography has always been a democratizing art form, but it wasn’t until fairly recently that it reached the realms of high art. Somebody could get a Brownie camera and take a picture of their family even if you made 15 cents an hour. You could save up enough money and go sit down at a studio and share that image with your family.

I think between Instagram and cell phones, we’re kind of coming back to that and it doesn’t take a $15,000 or $20,000 camera or grants or anything like that. It just takes you saying, “Hey, this is the story as I see it, that I want to broadcast it to the world.”

R&K: A lot of your captions are very short. Do you spend any time recording people’s stories as well?

AT: I do, and it’s kind of strange because I both love and hate writing. It’s a process to do a story justice and I do have a couple of stories that I’ve written on Instagram before. Sometimes, I write them down. But sometimes the stories are hard to write so I carry them with me. I may share them from time to time. Sometimes, there is no story beyond other than, you look awesome today, may I take your picture?

R&K: Why do you make your particular aesthetic choices?

AT: I think black-and-white is classic when it comes to street photography, and I think black people, in particular, look amazing in black and white. To me, that comes through the photography of people like Gordon Parks or VanDerZee. I love that aesthetic and I’ve loved it for a long time.

The reason that I crop as I do is mostly to focus the way I see the scene. Sometimes the picture is the details—it’s a glint in somebody’s eye or somebody’s earring. Those are the things that help us view another level of humanity and keep it from being voyeuristic. These choices also reinforce the fact that this isn’t me walking around with an expensive camera and just shooting people from across the street. Not that there’s anything wrong with that, but mine are photographs of relationships. Even if it’s a 10 minute-relationship, it was still there and it was one of vulnerability and permission. I think that can sometimes be lost in street photography quite honestly.

R&K: What’s your involvement like with the DC Street Photography Collective?

AT: I am heavily involved with it, which is kind of strange because I worked in isolation forever. We do photo ops, critiques, and even have a group show coming up. I find it to be tremendously helpful to be part of a collective. How I frame shots and how I look at things is different now. It’s really great to work with people who are better and more knowledgeable than you. I also play guitar and when I used to live in Tuskegee, Alabama, there was this old Haitian guy who use to tell me, “Ashley, the only way you’re going to become a better guitar player is to play with people better than you.” That kind of stuck with me. I think being a part of that collective is an opportunity to play with people better than me and to grow and learn from their expertise.

R&K: What do you hope people take away from your work?

AT: I hope they take away a sense of humanity. I hope that they look differently at the people that maybe they would have just passed by differently. Because it’s easy to do when you’re middle class, isn’t it? Even though I have a large mixture of people in my photographs, I think the ones nearest and dearest to my heart are the ones who sort of operate on the fringe of society for one reason or another. I hope they take away the fact that they’re human too and there are stories there.

I always like it when people comment on my photos because then I’ll tell them more of the story behind the photo. Not only are you affirming someone’s humanity, but you’re also telling your own through sharing those connections. I hope some of that comes across in the work because I think that’s the biggest part of it. Be human, stay human.

This interview has been edited and condensed.