Ana Aragão: Porto, with a Bic Pen

This week on The Trip podcast: Artist Ana Aragão on her detailed dreamscape drawings and her muse, the city of Porto.

This street I’m staying on in Matosinhos, just north of Porto, where the streetcar scatters seagulls, joggers brush past longshoremen, and old men drink their coffee and sigh, is everything I want from Portugal. But the most endearing thing about Brito Capelo street, I think, is the quiet anarchy of the architecture here. Hulking blocks of raw concrete on one building, while next to it is an aging ballad of stucco and balustrades and then next to that is a deeply Instagrammable old storefront covered in faded aquamarine tiles. It’s a mix of architectural cucina povera and grand brutalism, all running down to the port where the new cruise terminal looks like a royal cousin of the Guggenheims in Bilbao and New York City.

This is a land of architectural giants, home to two Pritzker-prize winners, Eduardo Souto from Porto and Siza Viera, who was born right here in Matosinhos, which is two more Pritzker winners than New York City has ever brought into the world (sorry, Newark and Tarrytown don’t count).

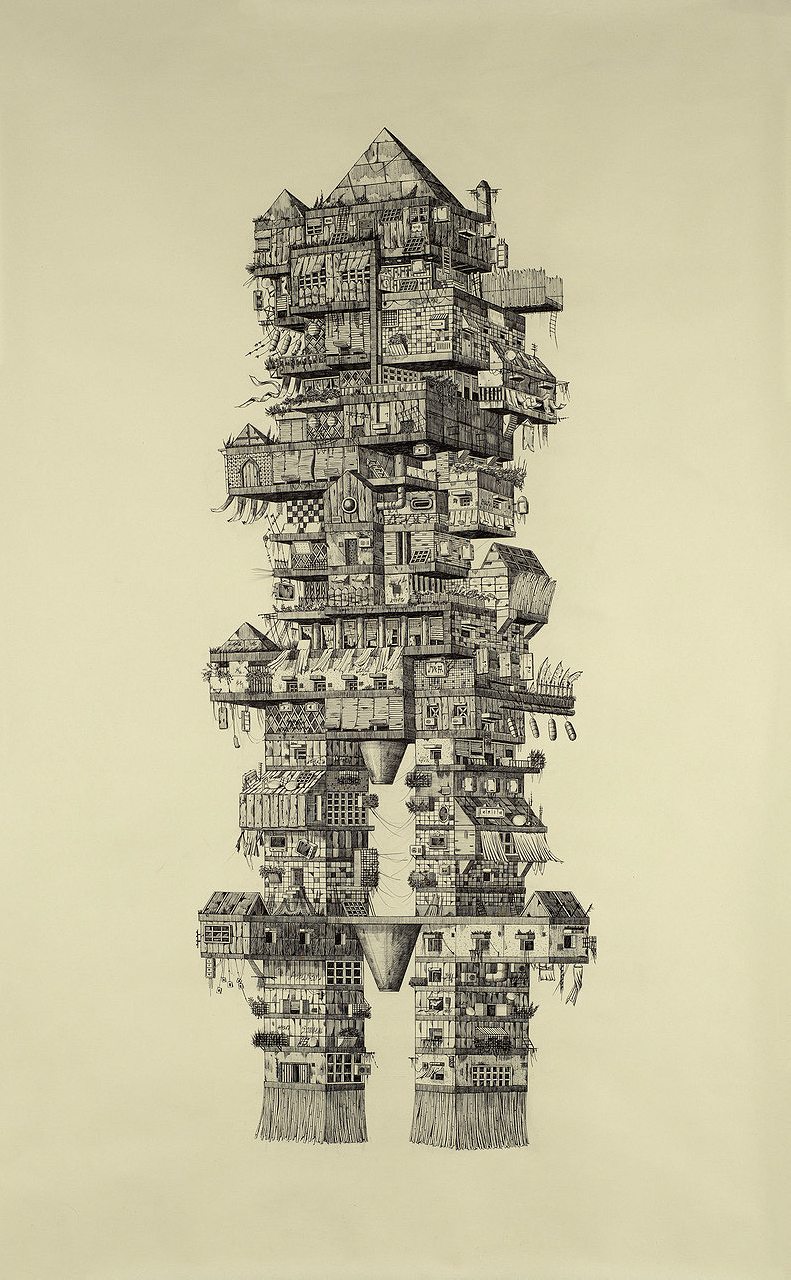

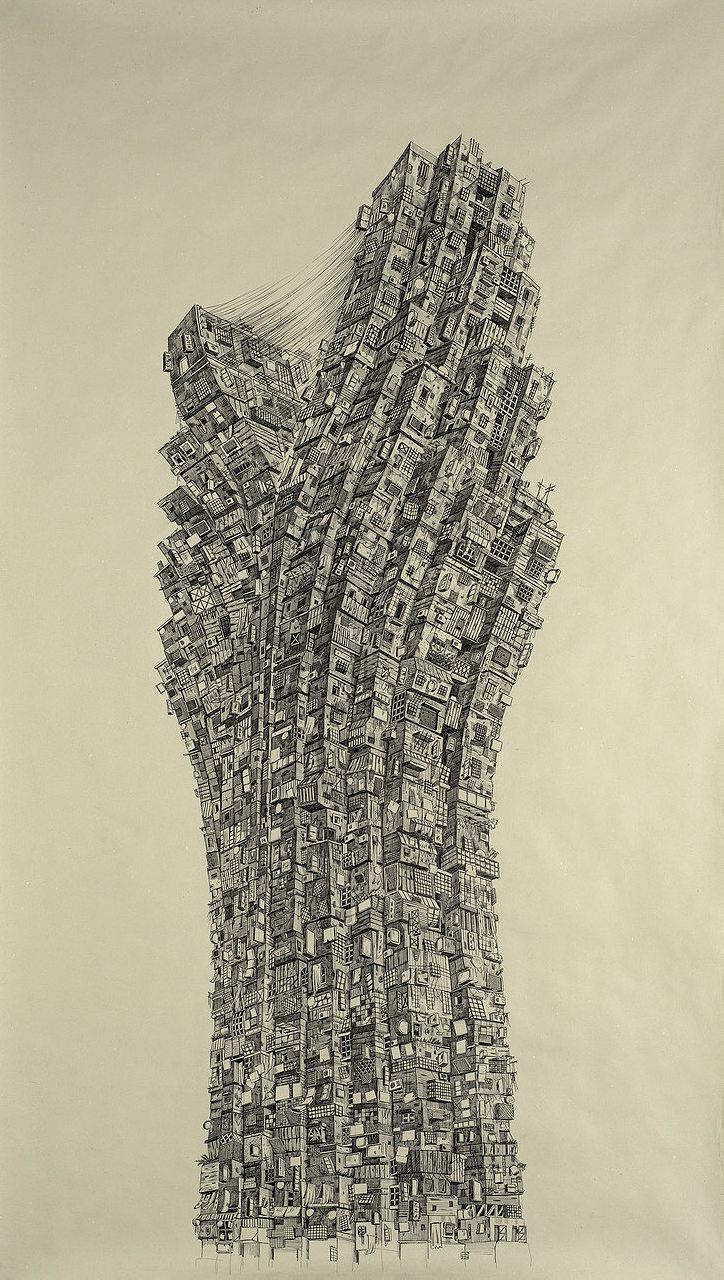

I can’t help but think that the obsessions of these Portuguese builders and dreamers are the same stuff that animates the work of today’s guest, Ana Aragão, who left her architecture studies to instead draft her own parallel worlds through her artwork. I would have some difficulty telling you what her remarkable work is like just using words. They are drawings, sometimes using nothing fancier than a Bic pen on paper, ranging from hand-held to mural-size, always with an astonishing level of detail, recreating and riffing and recomposing the buildings and the skyline of her city or of the Tower of Babel or other astonishments of architecture, then infused with a bit of magical realism. Her work is exhaustive, obsessive, like the fevered sculptures in Close Encounters of the Third Kind. You see it and immediately you know an unusual mind is behind it. It’s why I wanted to crack open a bottle of Port Wine with Ana, break into that brain a bit, and see what it says about her and about the city that made her.

Here is an edited and condensed transcript from my conversation with Ana. You can listen to the full episode, for free, on Apple Podcasts, Stitcher, Spotify, or wherever you get your podcasts.

Nathan Thornburgh: Okay, so Ana, you have brought Port wine, a fresh Port wine.

Ana Aragāo: Yes. Because the white Port wine should be drunk fresh, that’s important. You can also add tonic water, but I think plain is quite good.

Thornburgh: Quinta de la Rosa, which I’m pronouncing it in Spanish, which is terrible. I mean, we’re in Porto, Matosinhos but Porto and Port wine is the drink.

Aragāo: Port wine is the only logical drink I could give you.

Thornburgh: It is true, from the beginning of my days long before I even knew that Porto was a place, of course, you know of Port and old British generally you drink it.

Aragāo: Exactly, you don’t even think about the city. You think about the wine. It’s very logical that you drink Port wine and you present it to someone that’s coming from far away.

Thornburgh: Am I going to make you leave me with the bottle, what am I going to do with the entire bottle?

Aragāo: Of course, it’s for you. I wanted to choose properly but I had to run to the store like a crazy person, but that’s my normal way of living. Now, we Portuguese, that’s a characteristic we do have. You probably do have too but Portuguese people are used to … There’s a Portuguese word that I cannot translate. It’s called desenrascar. It’s like you have to arrange a method urgently to solve some problem, and we’re very good at that. Solving a problem on time and with great imagination.

Thornburgh: All of that in one word?

Aragāo: Yes, all that in one word. That word in Portuguese is quite funny. We do have that characteristic. For example, I studied in a German school. If you ask a German person to solve something in five minutes of the problem having to be solved, they will panic. We don’t panic, we live that way consistently. We solve things five minutes before it’s done.

Thornburgh: Always improvising.

Aragāo: Always.

Thornburgh: Always finding a way.

Aragāo: Yeah, it’s improvising, but funnier.

I think the most important things in life, you don’t decide.

Thornburgh: How did you go to a German school? Was that here in Porto?

Aragāo: Yes, it was in Porto. No apparent reason besides the fact my mother also studied there. She studied in the German school because maybe it was close to her home. Then she put me also me and my brother there and it was good because I still don’t understand Portuguese people working. I still don’t and I work in Portugal since forever, 10 years since I’ve been working, and I do not understand the Portuguese working style.

Thornburgh: Because the Germans taught you the meaning of work?

Aragāo: Yeah. The meaning of time and schedule. Two it’s two, three it’s three, four it’s four. In Portugal, no, that’s very flexible. It’s like liquid or the time is liquid. It’s two, but it can be three and then it can be four and it can be tomorrow. Everything can be arranged.

Thornburgh: That’s amazing. I had noticed you broke off a very appropriate sounding Genau. Obviously you have the German skills, but the thing that really sticks with you is this appreciation of the value of punctuality…

Aragāo: Yeah, I’m a bit of a freak.

Thornburgh: Yeah, that one of the defining characteristics of the people. There’s a dark side to the German obsessions with efficiency that sometimes I resent here in Southern Europe. I remember going to Cefalù in Sicily, right around the time that Germans were making absolutely insane demands on all the Southern European countries and just being very German about it and jerks. They were demanding austerity, insane measures, and all this stuff, and yet Cefalù was just full of Germans trying to get a little bit of that sun, a little bit of that Southern mentality, trying to relax, trying to get out of their skin a little bit. I thought, you can’t have both, you can’t come here and just eat ice cream all day and lay out on the beach and enjoy the tremendous love and hospitality of Southern Europe, then when it’s time for the loan to come due…

Aragāo: Yeah, that’s true.

Thornburgh: It is the remarkable kaleidoscope that is this continent.

Aragāo: It is.

Thornburgh: Have you lived outside of Portugal or have you always been here?

Aragāo: No, almost never. One year in Barcelona. It was an amazing year and I loved the city of course. Besides from that, I’ve always lived in Porto, so I’m really from here, very Portuense.

Thornburgh: How do you feel about, I mean, so many of the people that I have met here even in Matosinhos have spent huge amounts of time or are still actually living abroad. What is it like to be someone who stays and you’re young and talented and ambitious and loved and you can go and work anywhere and do anything you want to do, and yet here you are staying in Porto.

Aragāo: It’s true. It’s a question that I’ve asked myself because for example, my brother has emigrated, he lives in Germany. Everyone is abroad basically. A lot of my friends, a lot of architects, I’m an architect of education, a lot of architects. A lot of my friends are abroad because in Portugal, although it is a great country and it has so many qualities, but in terms of your work being recognized properly in terms of value, in terms of living costs and everything, for young people, it is not that easy.

We are not well-paid, et cetera. It’s not that easy, so of course you have much better opportunities abroad. I decided it, but it’s not a decision, I think the most important things, you don’t decide. In my work I didn’t decide to become an illustrator or an artist and architect. I just stayed on the path, and it started to make sense. To stay here is also a question of pride and a question of challenge. I like challenges, so I think it’s a challenge.

Thornburgh: What’s the pride? Just pride in being Portuense, pride in staying here.

Aragāo: Your heritage stays with you. In my case of course I don’t have any pretension of representing a city, but I do representation so it’s funny because you can joke with that.

Thornburgh: You actually represent the city.

Aragāo: I actually represent the city, not in the way that the mayor represents the city, but I do represent the city.

Thornburgh: You create representations.

Aragāo: Exactly, and I think it’s important to have a place to have a center. My husband for example, he travels a lot. He travels almost the whole year and I stay here most of the time. I love to travel but he travels more than me and I think it’s important to have a center, and I never felt like that, but I don’t exclude the idea of going abroad because my works are site-specific, almost.

With the passing of time, I understand better that I cannot do some piece that is abstract. Okay, I have one or two pieces that are abstract in the way that they are almost universal. My Babel Tower that I put now in Lisbon, but the rest of the time I do work for a place, and that is why it is so important to have a center, but then to go to the places and understand them and to feel the place. I did the work like that early last year in Macau, and it was amazing because I had to live there to understand it and then to produce a piece.

Thornburgh: Since we are here drinking port wine and we’re in Matosinhos, which is very near Porto. Tell me something about the city that inspires you in the work that you do because it is, as you had said very well before, it’s like very specific to this place. You’re very connected to it. What should people know about Porto that finds life in your art?

Aragāo: We have great hospitality, I would say, and that’s very special because we have that also to each other. It’s very friendly and it is very intricate. It’s very dense, and it’s still very local in the way that the center is still local. I hope the politicians understand that and I’m sure they will, hopefully…

Thornburgh: You’re, you’re making a face like maybe they won’t.

Aragāo: Yes.

In Porto, we don’t have the light of Lisbon, but we have a mystery.

Thornburgh: But ultimately, we’ve talked about being overrun by tourists and so on. But you, you still feel the small alleys, the dense, local…

Aragāo: I do, and I work in the center, I work in the center and I still feel that. For me that’s the soul of a city. The people that live in it, of course, and the way we treat each other, we are still very friendly with each other. I don’t feel that so strongly, for example, in the capital, because of course it’s a bigger city. Of course, it’s the capital, so it’s a bit different, although it’s an amazing city, and it’s very, very beautiful. The light of Lisbon is just magical. Here in Porto, we don’t have that light, but we have a mystery. We have another mystery. If you walk at night, for example alone, it’s still okay. We are very cheerful, we are bright people and for me that’s the most important thing about Porto. We are generally speaking of course, but we are nice people. We are open people. We are very honest. We say the truth.

Thornburgh: Yeah, I mean, I have seen more kissing in the last three days than maybe I’ve seen in years. It’s like every time I’m talking to someone, it’s an invitation for all of the Portuguese who are near and everybody from Matosinhos, we’re in the center to just come and kiss the person I’m talking to and just be like hi.

Aragāo: When we hug, yeah we hug, we kiss and everything.

Thornburgh: It’s incredible. It’s just like Porto is one giant cuddle puddle that I can tell, people are so kind to each other and they’re so nice and everybody feels really validated and there’s this wonderful wine. It is a little, it’s Elysian. It’s paradisiacal. You just like that’s existence as it should be just kisses and wine like please.

Aragāo: Yes. Let’s go there.

Thornburgh: How does Porto live in your work in a way that if you had been born in Lisbon or, God forbid, another country? How is it specific to this place?

Aragāo: I would say the organization or the country, the confusion that you feel in my work where you have some rationality, but everything’s quite confused. Everything’s quite obsolete, or the time has passed through the buildings for example, you feel that in my work. Everything has a bit of Porto.

Thornburgh: There’s decay.

Aragāo: Exactly.

Thornburgh: There’s the gray layer. Yeah, that’s fascinating.

Ana Aragāo: Yes. More than in the beginning, now I’m feeling that I’m going towards that. A lot of people love my initial work. It feels more naïve. Now I’m beginning to be a bit darker. People look at my Babel tower and say, wow. This is Game of Thrones in there and I never saw Game of Thrones, or they say, this is terrible. They say a lot of movies that I’ve never seen, but people relate to a darker side, and I like that, and I’m comfortable with it.

Thornburgh: It’s coming at a time also where Porto is renovating itself in the center, where they’re power washing the walls of old buildings. Imagine if they went through and just re-painted every building and in Old Havana, like it wouldn’t be the same. You would lose a national, an international treasure, a global gem of beautiful decay.

Aragāo: I hope that economic reasons don’t accelerate this gentrification that’s happening in the center. Because I don’t know if foreigners can understand, but we really cannot afford the rents for young people, who don’t earn that much, to live in the center. I’m not talking the center, center, I’m talking near here in Matosinhos. It would be really important that political and economic power understands that, because we are the soul of the city. Of course we love tourists, but they are not the soul of this city. If tourists come here and they only meet tourists, that’s not very interesting then we will be a resort, not a city.

Thornburgh: There is a dark cloud that is gathering for so many of us, right? I know why your work is making this turn, but it feels like really vital, really important to communicate and express and pass on the urgency of those questions. This is the city that is your muse, and it has a path that is turning badly, right? I mean, maybe I’d say that’s your job. I know you’re not looking at it as you’re saying you’re not an artist, but you’re an artist and your job is to communicate these great, these kind of gathering dreads in a way that people can’t do.

Aragāo: I think it’s very important that you understand how the future could be, to take decisions now. I see my work sometimes as, not a warning, but it’s somehow like a premonition. Look, this could happen this way. Try to think if you want it this way or another way or let’s imagine what could be. It’s very important that we keep our imagination alive and what could be, if not, we’re just automatons repeating ourselves.

Thornburgh: This word kept popping up when I was going through your pieces of art, which now I feel like I haven’t spent enough time on each one or I need to see them in person to get the full two meters. But it felt oracular, like an oracle. It’s like you’re throwing bones in the fire and you’re seeing some, truth that is like a vision, but it’s still like very true on some level. That’s, I guess, the power of it. It’s just people need to imagine how it’s going to be. What will this city look like if all the projects had been built that had been mothballed? If an earthquake hits Lisbon, all of these things it’s incredible. It’s such a pleasure to hear you talk about that process because as anyone will see if they go in and look at your art in person or online there’s a power behind it like a motor there that it’s so cool to just be able to look under the hood and hear from you how it goes. Thank you.

You can listen to the full episode, for free, on Apple Podcasts, Stitcher, Spotify, or wherever you get your podcasts.

Up Next

Eduardo Leal: Coming Home to Porto

Ansel Mullins: From Istanbul to Porto

This week on The Trip Podcast: Ansel Mullins on the lost city of Istanbul, the glorious multitudes of Turkish meatballs, and the art of raising kids abroad.

From Portugal to the Ironbound

New Jersey’s Portuguese community returns to Newark to celebrate their culinary heritage.

Saint Sardine

On the eve of Lisbon’s annual sardine-and-beer bacchanal St. Anthony’s Day, Cara Parks looks at the uncertain future of a celebrated fish.

You’d Be Upset Too if You’d Missed Out on Beach‑Side Donut Delivery

Did Portugal come up with the best food-delivery app in the world?