Photographer Tiffany L. Clark challenges the perceptions of self-harm through her ongoing series.

When Tiffany L. Clark decided to create her first documentary photography project, it was a personal connection that inspired her to focus on the difficult subject of self-harm. Through A Release: Stories of Self Injuries, Clark wanted to challenge perceptions about self-harm by showing the quiet moments of four women who struggle with it every day.

The New York and Minnesota-based freelance journalist stopped by the Roads & Kingdoms office in Brooklyn to discuss what she learned about herself while doing this project, her work with NGOs, and how photography connects her to her grandfather.

Tafi Mukunyadzi: When did you realize that you wanted to be a photographer?

Tiffany Clark: I started doing photography in high school. My parents—particularly my mom—always had me involved in the arts. It was important to her for me to appreciate the arts, and my grandfather, my mom’s father, was really into photography. It was actually his World War II photos were some of the first intense photos that I ever saw and also felt connected to. My grandfather passed away before I was able to actually start taking photography classes. He always tried to push the camera on me and like tried to teach me what an F-stop is. At that time, I was kind of an angsty teenager. I don’t want to know this. When he passed away, picking up a camera was my way of reconnecting with him. It wasn’t one of those things where I felt like I’m going to be a photographer for the rest of my life, but I was like, you know what? I want to just do this. It brings me joy. It helps me connect with my grandfather and relate to other people.

Mukunyadzi: Do you think that push to get you into the arts has influenced your photography?

Clark: I think it definitely helps—not so much like storylines and ideas, but when trying to recreate an image. I actually have found, over the years, that I don’t like to go and see photo exhibits. I’d almost rather go a painting and other portraitures because it’s another form. It’s not looking at the same photography over and over. When I was in college I was an overall art major, I would say I was definitely at my most creative in terms of photography back then because of all of these other [art forms] I was forced to do. Since I moved to New York, it’s been pure photography, so I’ve been trying to see performances, dance… to get [different] influences.

Mukunyadzi: How has your style of photography changed over the years?

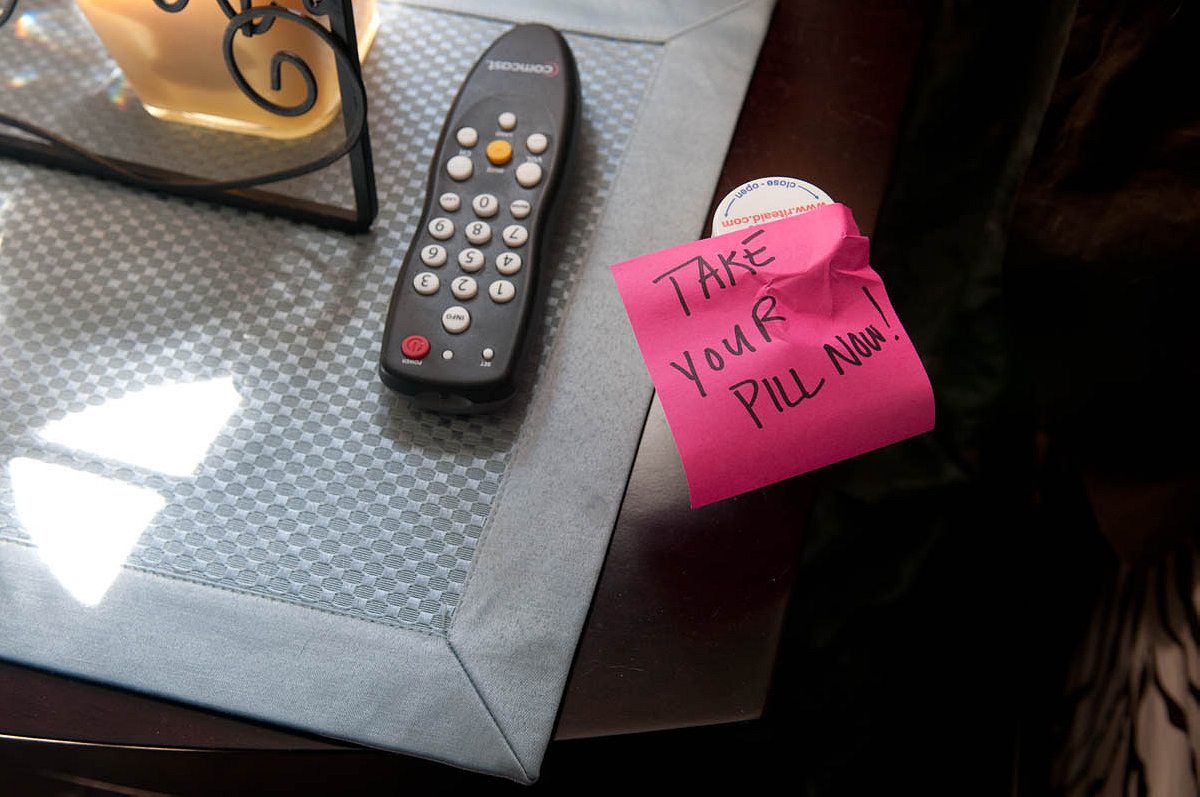

Clark: When I started, it was much more fine art. Everything had to have this deep meaning. I studied photojournalism and documentary photography, so I like to call myself a fine-art documentary photojournalist. I like things that are really beautiful. What is beautiful to me? I like the really peaceful, silent moments [when I’m photographing]. I like trying to capture the quiet moments.

Mukunyadzi: There are a lot of silent and quiet moments in your series, A Release: Stories of Self-Injury. What inspired you to focus on this particular subject?

Clark: Yeah. That project has been put on pause for a while, but it is something I do want to continue.

It was my first documentary project, and I was just trying to come up with ideas. I don’t even remember how it exactly came to mind, but I had friends in college who self-harmed and I saw on TV the stereotypes—like it’s attention-seeking—that people always assumed about the people who self-harm. That’s not what it’s about, and I wanted to talk about it in some other way.

Mukunyadzi: How did you find the four women who were the subjects of the series?

Clark: I actually found them online on an open forum. I posted in the forum about my project and said that I was not here to gain fame off of what they’re going through. It has everything to do with mental health. I want to tell real peoples’ stories.

Mukunyadzi: Was it difficult to get the women to trust you? What was it like to try and build a relationship with them?

Clark: Yeah. I think part of it was just being very transparent from the start and saying, this is why I’m here. I’m here to tell your story, however that story plays out. I’m not going to be like, “See, you’re just as crazy as everyone says….” But if something comes up, I’m also going to photograph that.

Mukunyadzi: What did you personally get out of the experience of shooting that series?

Clark: It was very difficult to hear some of their stories, because one of the reasons people harm themselves is because of something else that has happened in their life. Each time I met with all these women, I realized that I needed to take a break for myself.

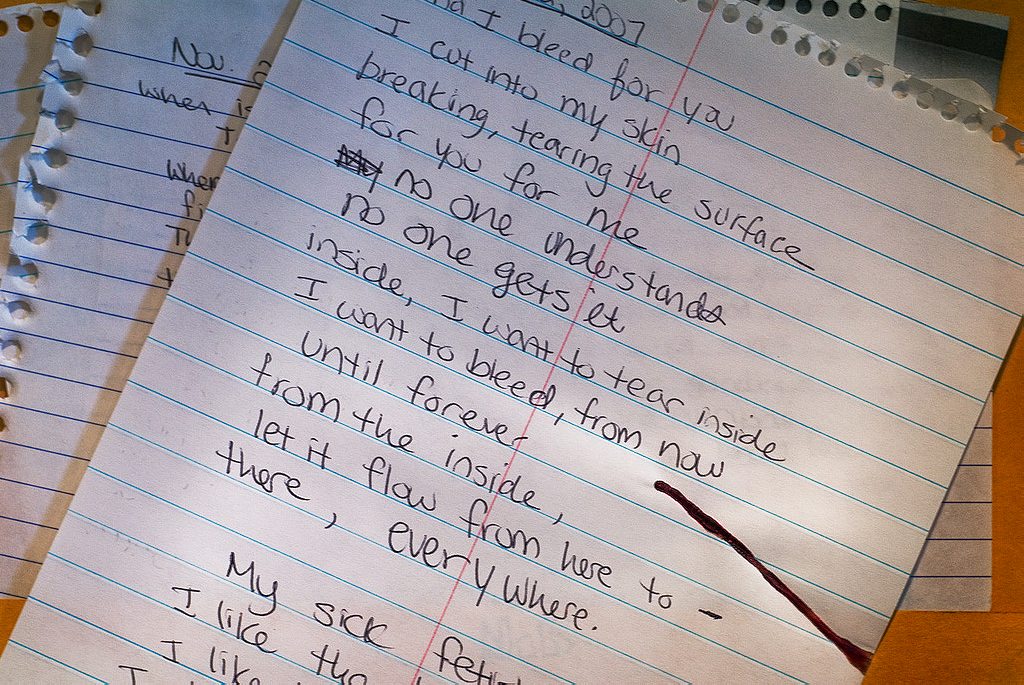

But what I really wanted to do was to help bring awareness [about this issue]. I’ve tried to get this story and photo series out many times. A lot of magazines and publications have said yes, but it’s very graphic, which is always been very interesting for me. There are pictures of war that are, I think, much more brutal, but it’s easier for our brains to wrap around the idea of someone else hurting someone, versus someone doing it to themselves.

Mukunyadzi: You said the project is on hiatus, but you want to expand it in the future. How would you do that?

Clark: I would love to expand it. Self-injury affects so many different communities. It isn’t just females, so I would like to photograph a man, people who are transgender, people of color. It also affects people of various ages, too. The series is really about just bringing awareness to the subject in a way that’s not glorified.

Mukunyadzi: What are you working on now? You’ve done some photography work with NGOs. Is that something that you’re interested in doing again?

Clark: I would say for almost the past three years, I’ve been doing more photo-editing and retouching. I’ve started to do a bit more lifestyle photography. If the opportunity presents itself, I wouldn’t mind. I kind of stumbled into the projects I did with NGOs, like the Liliana series.

Mukunyadzi: What was that project about?

I signed up for a photography workshop that was being held in Mexico City. And at first I wanted to shoot luchadores, the Mexican wrestlers, and I had not prepared. I showed up and I was like, I’m in a different country, don’t speak Spanish. I don’t know how I’m going to do this. I kind of wandered the streets for a couple of days. One of the volunteers for the workshop also worked with some NGOs and she said there was an NGO that I could partner with that would probably let me photograph. So, I was introduced to people from this organization who take young girls, who are pregnant, just had their babies, or are struggling with addiction, off the streets. The group would teach them skills like cooking and cleaning and taking care of their babies. They’d help them get a job.

Liliana, the girl I was specifically photographing, was 16. This was in June 2008. There were girls as young as 13 there.

Mukunyadzi: Have you been in contact with Liliana since then?

Clark: No, but it would be interesting to see how she’s doing. Did I have any effect on her positively or negatively? Because at the end of the day, we all have our stories and we’re hoping that we’re helping people, not making their lives harder.

Mukunyadzi: What do you hope people take away from your work?

Clark: As far as being photographed, I hope people have a positive experience. I hope I shed some light on their life and that they shed some light on my life.

For the people who view my photographs, I hope they learn something new. I’m always hoping for some kind of positive impact. Whenever I’m trying to take a photograph, I want my work to have an impact.

This interview has been edited and condensed.