The Most Righteous Team in England

A historic upset, a heart-breaking relocation, and a fan-fuelled revolution: the improbable history of AFC Wimbledon.

Niall Couper is UK spokesman for Amnesty International. If you follow the news, you’ll understand that means he’s a busy man. You’ll also understand why I, having never met him, was nervous about emailing to ask if he’d like a chat about football.

He replied within three minutes: “Friday?”

I shouldn’t have been surprised. Niall Couper is a Wimbledon fan, and Wimbledon fans are always happy to talk football. In fact, it is their enthusiasm for the game that has made Wimbledon possibly the finest football club in the world.

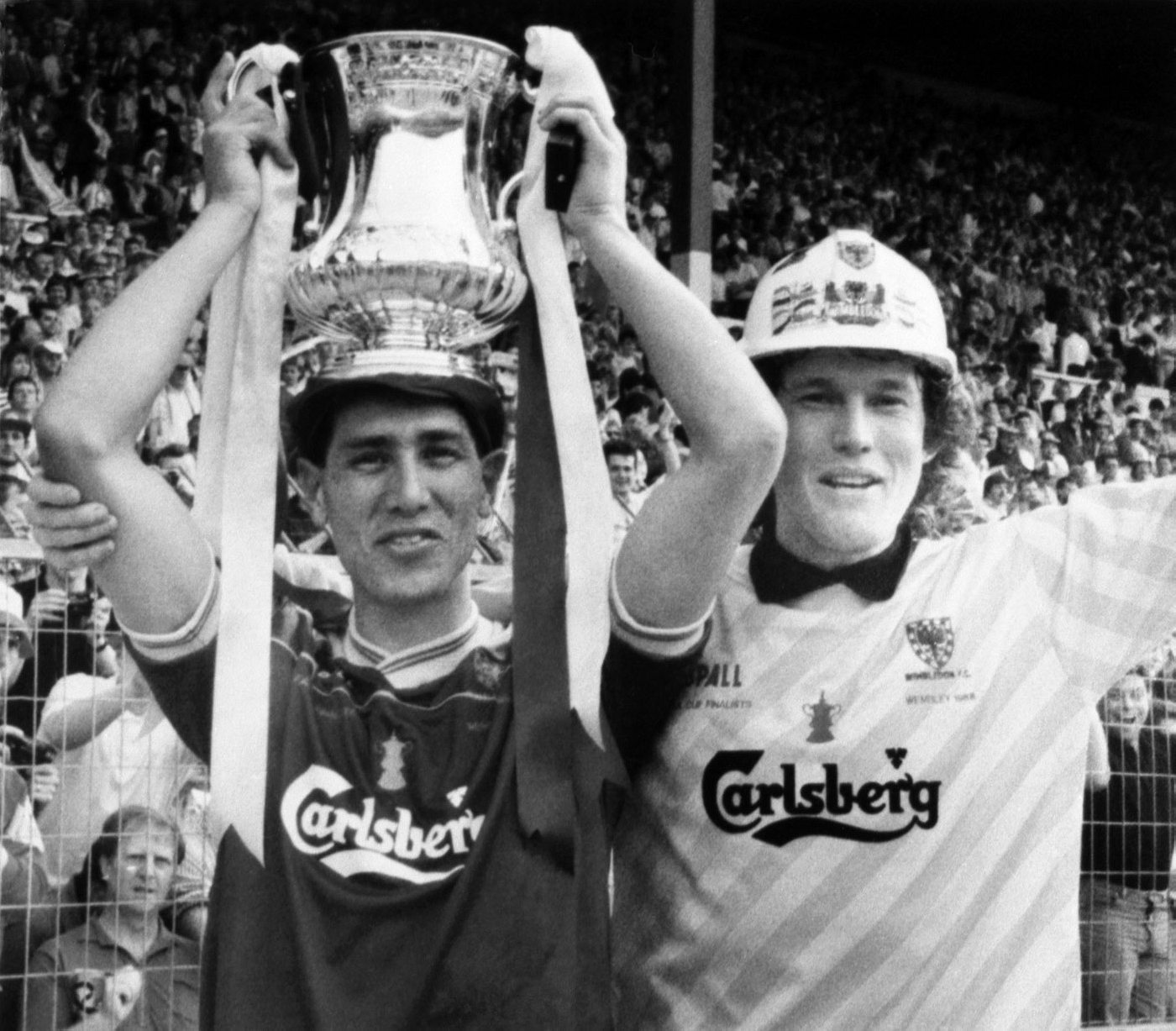

I first heard about their club in 1988, when it met Liverpool – the aristocrats of English football, the best team in the country, if not the world — in the FA Cup final. My great-grandmother lived in Wimbledon, a patch of south London better known for tennis, but the reason my mates and me, and millions of other Brits, cheered on the boys in blue had nothing to do with geography, and all to do with something far more important.

Wimbledon scored first, a header by Lawrie Sanchez, chiefly noticeable now for the shortness of his shorts. The iconic moment was later in the game, on the hour mark, when Liverpool’s John Aldridge – a moustachioed Irish international in his club’s famous red strip – lined up a penalty against Dave Beasant, Wimbledon’s goalkeeper, resplendent in yellow shirt and Brian May hair.

Aldridge shot to Beasant’s left. Beasant dived, full stretch, turned the ball round the post. Aldridge sank to his knees. Beasant snarled. 14 May 1988: the day when Wimbledon won the FA Cup 1-0. It was perhaps the biggest shock that the world’s oldest football competition has ever seen.

“I was there. I was behind the goal, I saw him dive,” said Couper. Couper has silver-tinged hair and the careful enunciation that is required if you’re the voice of Amnesty International. He was just 14 years old at the time, and could still describe every play of that match with the kind of detail he would normally reserve for a live human rights emergency.

“It is weird everyone remembers that one because most of Beasant’s saves in the first half hung in the air far more. But people forget that we had a lot of chances too.”

Liverpool fans were no doubt heart-broken, but neutrals like me were delighted. This wasn’t because Wimbledon played attractively. The players were unsubtle to the point of brutality, and their attacks were unimaginative: a hoof up the pitch and a scramble in the goalmouth. We watched because of what they represented: hope.

Even in Britain, even then, most people only followed the top clubs – Manchester United, Chelsea, Liverpool, Arsenal, the usual boring suspects — but these global mega-brands are just the glittering summit of a tall and broad pyramid. The Premier League is connected to the one beneath it, and that to the one below that. Finish at the bottom of the league, and you go down and down and down, all the way to the bottom, where games are played on Sundays by 22 blokes in a park.

Wimbledon only climbed into the full-time Football League in 1977. Yet, here they were, barely a decade later, winning the greatest prize of all. If Wimbledon could do it, could come bursting out of unfashionable south London and beat the best, then so could anyone. It should have been a movie.

“To talk about the Wimbledon story, it started a long time before the FA Cup win, the real romance of it started a long time before that and this is the point, this is what a lot of people don’t realise. And I think that to write a true story about us, you need to know that very early history,” explained Ivor Heller, a local businessman who started following the Dons, aged 11, in the 1970s.

In the 1970s, Wimbledon was easily good enough to be in the top four divisions, the Football League, where fully professional clubs played against each other. But first it had to win entry. To enter the League in those days, clubs had to apply for approval from the other members, which meant another club had to go down.

THIS GAVE FANS ONE OF HUMANITY’S MOST POWERFUL MOTIVATORS: A GRIEVANCE

Not surprisingly, few League clubs were prepared meekly to commit suicide in that fashion, even if their presence in the elite was unjustified, and it took Wimbledon three years of trying before it managed to shoulder one of them aside. This welded the fans into a coherent whole, by giving them one of humanity’s most powerful motivators: a grievance.

“People ask me what my best day as a Wimbledon fan was, that it must have been winning the FA Cup,” said Heller, who is short, bearded and charismatic, like a woolier Danny DeVito.

“But that day when we got elected to the league, that was a party. I was 13 years old, doing the very best I could to get my hands on any alcohol that I could. And we had a massive party, it was unbelievable, Wimbledon were in the league.”

The Football League was packed with the game’s aristocrats, clubs who had been there since it was founded in 1888, and others who joined in its first decade or two. Even the second rank of clubs – Aston Villa, Sheffield Wednesday, Everton, West Bromwich Albion, Wolverhampton Wanderers – were household names throughout Britain. Wimbledon, who were they?

But Wimbledon fans didn’t care that no one knew them, that their Plough Lane stadium was dilapidated, that their budget was small. In 1977, their rocket launched, and its trajectory was near vertical.

“The real moral in the story is that 10 years later we won the FA cup. Ten years later, out of a ground like Plough Lane, absolutely impossible to fathom. It will never happen again, that is an absolute certainty,” Heller said with a laugh.

Sadly, the story did not end with the FA Cup final, with the BBC commentator praising “one of the great Cup shocks of all time”, with Princess Diana applauding demurely and the Wimbledon fans in raptures. If the fans thought they had been tested by three years of being denied promotion, they had a far harder test to come.

The seeds of the disaster were sown at least five years before that glorious Final, back in 1983, when fellow London club Tottenham Hotspur floated on the stock exchange and opened football’s door to a lava flow of hot money. Those were the years of Margaret Thatcher, when new wealth was revolutionising everything in Britain, creating a brasher, brighter, greedier, less equal country. And football was no exception, Blackburn Rovers smashed the British transfer fee record with a £3.3 million pound bid for Alan Shearer in 1992, then smashed it again two years later, with a £5 million pound bid for Chris Sutton. Those sums look quaint now (In September, Real Madrid paid £86 million for Tottenham’s Gareth Bale), but they still left Wimbledon struggling to compete.

Wimbledon quit Plough Lane in 1991, following a report that recommended that the terraces – areas where fans stood up to watch – be abolished in the top flight, to help improve safety. Plough Lane was falling apart anyway, and had no place in this brave new future. The club began to play home games at Crystal Palace’s stadium nearby. The fans didn’t know it, but they would not play a real home game for more than a decade, and that under vastly different circumstances.

This was when Rupert Murdoch’s satellite television channels moved into Britain and began to broadcast football, paying huge money for the exclusive rights. The game changed out of recognition, with fans needing to be richer to afford tickets, and clubs needing to be richer to afford players. Wimbledon’s owner – Sam Hammam, a Lebanese businessman whose involvement was a harbinger of foreign money’s growing influence on the game – spotted a moneymaking opportunity, and began to sweat his asset. He sold off Plough Lane for redevelopment; he pulled money out from the television deals.

As the decade wore on, the effort started to show. Wimbledon struggled to compete with its peers. It gradually lost its hold on the top spots in the Premier League. By the turn of the millennium it had dropped into the division below. The other clubs were just too rich, Wimbledon’s owner was just too greedy, and it lacked the fan base or the asset base to raise the sums needed to catch up.

This had been coming for a while and Hammam, the mercurial investor behind the club, had been exploring options of moving his club to a more lucrative base. He looked into Dublin, and Belfast, but Milton Keynes was the option that came up most often.

“(Hammam was one of the) great bastions of how to make money out of football clubs. The only trouble is that every club they owned ended up homeless, which is sick,” Heller said. Hammam made a reported £36 million out of Wimbledon, following an initial investment of £40,000. It wasn’t even technically an English club anymore, being owned by a tax-minimising vehicle in the Virgin Islands. That is by any standards good business, but it didn’t make for good football.

“A football club isn’t about who you can compete with, it’s ‘find your natural level…find your natural level and be what you’re meant to be’, which is a club to represent your community. That was what someone like Sam couldn’t get his head around, he never really understood that,” said Heller, smiling ruefully.

Milton Keynes is what Brits call a New Town, a settlement created after World War II to take population from the cities. It is laid out on a grid pattern. It lacks the nooks and corners of an ordinary town, though it compensates by having a lot of roundabouts. In August 2001, the club – which Hammam had sold control of to some Norwegian shipping billionaires – said it was moving there. For the fans, who found out in a letter just before the season began, exchanging South London for a new invention was a catastrophe.

It was not just the fact that Milton Keynes was in Buckinghamshire, meaning a 150-mile round trip to get to home games, but also that moving a club violated everything football was for. It was practically cheating. It broke the rules of the pyramid. Communities created clubs, and then the clubs battled for a place at the top. If Milton Keynes wanted a football club, they should build one from the ground up like everyone else. If Wimbledon relocated to Milton Keynes, it wouldn’t be a club, but a franchise, and English football didn’t do franchises.

IT IS NO EXAGGERATION TO SAY THAT THE FUTURE OF ENGLISH FOOTBALL WAS AT STAKE

“How a football club has progressed is part of the civic pride of a local areas. You can’t think about Liverpool without thinking about Liverpool. It’s hard to think about Glasgow without thinking about Celtic and Rangers,” said Kris Stewart, a fan and political activist who has stood for local elections in Wimbledon on a far-left platform.

“That doesn’t transfer, you can’t have someone in Milton Keynes being proud of southwest London. It doesn’t make sense, it doesn’t work, it’s just obvious.”

The fans went to war. As the 2001-2 season wore on, their demonstrations got ever more imaginative. They inflated black balloons at home games, they turned their backs on the action, they wrote letters, they protested, they petitioned. They published their own programme – Couper, the Amnesty International spokesman, was the editor – which outsold the official programme four-to-one. Meetings of the Wimbledon Independent Supporters Association (WISA) became more about fighting the club’s owners than about watching football. The feud took its toll on the players. The club slipped to ninth in the League’s second division, and won more games away than it won at home.

Fundamentally, the debate was about two competing visions of what a football club was. Was a club just an entertainment business, like a cinema or a restaurant, that could be moved wherever its owner decided the profits would be highest and the costs lowest? Or was a club a community? Was it something that had thousands of stakeholders, fans who had a say in its future even if they didn’t technically own it? It is no exaggeration to say that the future of English football was at stake. If Wimbledon could follow the money wherever it led, then so could anyone. Manchester United could go to Singapore. Liverpool could play in New York. Chelsea could move to Paris.

The decision was down to the Football Association, the body that governs the sport in England, and after whom the FA Cup is named. It had sanctioned ground moves before – Arsenal previously played south of the Thames, in Woolwich, for example – but never such a dramatic example. The process dragged on, while the fans and the players had no idea of their future. The FA deliberated, and rejected the move. Wimbledon appealed, and the FA deliberated again. Wimbledon fans held a vigil outside its Soho Square offices. It was there that they learned on May 28, 2002, that the FA had changed its mind.

The club’s owners had said it would slip into administration if the move were blocked. The appeal considered a suggestion from Stewart that the fans could take over any remnant that emerged from bankruptcy proceedings, but rejected it.

“Resurrecting the club from its ashes as, say, `Wimbledon Town’ is, with respect to those supporters who would rather that happened so that they could go back to the position the club started in 113 years ago, not in the wider interests of football,” the panel of three ruled, thus giving the Wimbledon fans a fresh grievance, just in case the first one had worn off.

They had supported their club while it came from nowhere to the peak of English football, had supported it while its owner asset-stripped it, and then had to watch when another town came and took it away. Wimbledon Football Club was moving to Milton Keynes. The fans now had no club to support, no stadium, no players, no kit, no money, no manager, no backroom staff, and not even a name. What were they now fans of? Were they even fans at all any more?

“Football hurts, football hurts and it has to hurt. It has to hurt. You cannot understand the joy of football unless you understand the pain of it. And even Barcelona and Manchester United fans understand a little bit of that though they don’t really understand it,” said Heller.

Of course, that’s easy for him to say now. At the time, I suspect he would have used more swearwords. But at least he was ready for the decision. He had been thinking about what the club should do if the FA backed a move since the previous autumn, and had told Kris Stewart and others they should form a new club, should start again from the bottom, should work their way up the pyramid, should do exactly what Milton Keynes was refusing to do, should do it right, and show the Football Association how things ought to be done.

I’M TIRED OF FIGHTING. I JUST WANT TO WATCH SOME FOOTBALL

He had won over Stewart to his vision, and a couple of others. Now they needed to get all the other fans onside. There was a meeting of WISA planned on May 30. Some fans wanted to keep protesting, some wanted to try another appeal. There was no focus until Stewart, the left-wing political activist, who had been due to chair the meeting, but handed control away so he could speak, stepped up.

“I’m tired of fighting. I just want to watch some football,” he said.

Every Wimbledon fan can recite those words, which were what made the club’s re-birth possible. They can tell you just where they were when they heard them, in the same way they remember Beasant’s save in the FA Cup final. They marvel at them as others marvel at Winston Churchill’s “We will never surrender”. Stewart himself, who is big in the way a bear is big, just laughed.

“We had spent a year not really thinking about football as football at all, but thinking of a match in terms of what we did around it, what are we doing today? Are we selling t-shirts? Are we doing balloons? Are we staying after the game?” he said.

“And thinking, wouldn’t it be great to just watch a football match, to rock up at quarter to three and watch the game and then fuck off home or go to the pub and talk to your mates about it for a bit, whinge about the striker? That’s mostly what that was about.”

He won the hall. The fans voted in favour. They were starting again, and had less than a fortnight to create a club and find a league to play in. And they had to come to terms with the fact that they had dropped out of the elite, down and down and down, to the level occupied by blokes in a park. Literally.

The club that betrayed them was called Wimbledon FC. Their club was to be AFC Wimbledon, owned by the fans. And it wanted some players.

Apart from tennis and football, Wimbledon is known for one thing: the Common, a 1,000-acre open space that shades into neighbouring Richmond Park. In turn, Wimbledon Common is famous for one thing: the Wombles, a children’s television show about anthropomorphised rodents who recycle “the things that the everyday folk leave behind”. Wimbledon fans, conscious perhaps that they will be called the Wombles whether they like it or not, have adopted the name as their own.

Their new players inevitably had their trials on the Common. The club had hoped 60 people would turn up but their quixotic attempt to restore justice to football had caught the national imagination. They got 300 players to that first audition, and they had their team.

Now they needed a ground, and Heller found one at Kingsmeadow, a small stadium that was not technically in Wimbledon but not far away, being just south of Richmond Park.

The reconstituted club’s first competitive match was away to Sandhurst Town on August 17, 2002, a Berkshire side whose attendance record remains the 2,449 fans that came to see Wimbledon win 2-1. There were no stands, no stadium. How 2,449 people could see the pitch while basically standing in a field is something of a mystery, but a win was a win and the club was on its way. They lost their next game though, against a team from the Surrey village of Chipstead. This was far from the glittering heights of English football the fans were used to.

Nonetheless, more than 4,000 of them came to the Chipstead game and attendances remained good. In the Combined Counties League, the bottom rung of English football, getting 100 people to watch a game was impressive, so Wimbledon were always at an advantage. With support like that, their trajectory was soon vertical once more. In 2003-4, they went a record 78 games without defeat.

Wimbledon was promoted four times in eight seasons, bringing it back in 2011 to the brink of the elite game: the Football League. The League has changed since the harsh 1970s. You don’t need to win election anymore. If you win the division below you go up automatically. But that doesn’t make it easy. You still need to win the playoffs and Wimbledon’s fate, once more, came down to a penalty, the final kick of a shoot-out.

Danny Kedwell, the club captain, took six steps back from the spot, ran forward, shooting far to the goalkeeper’s right. The net bulged, and Kedwell ran exultant to the fans in the stands. The television commentator lost his mind.

“The fairy tale is complete, Danny Kedwell is the hero, and the fans’ club that started less than nine years ago are into the Football League. Wimbledon have a Football League club again,” he shouted.

It is hard to think of any normal circumstances that would bring together a hard left political activist, a small-scale entrepreneur, a spokesman for Amnesty International, a record producer, and a tax exile. But AFC Wimbledon isn’t normal circumstances.

Wimbledon is only on the lowest rung of the League, but it’s an elite club once more and the path to the top is – theoretically — open. But it won’t be easy.

“The differential between the top boys and the lower boys has grown wider and wider and wider. In the early 1970s, the differential between a fourth division player and a first division player was about three and half time the salary. Now, it’s in excess of 33 times,” said Heller, who is in charge of the club’s commercial activities. Without an oligarch or a sheikh or a financier or a sugar daddy of any kind, Wimbledon is always going to struggle to compete for the best players.

THE WIMBLEDON FANS’ YEAR AND A HALF’S WORTH OF HARD-RAISED CASH WOULDN’T COVER ROONEY’S SALARY FOR TWO DAYS

To put that in perspective, Wimbledon fans are currently trying to raise a special fund of £400,000 for the club to spend on its players. In the fund’s first 18 months, it raised £83,000, which is remarkable by any normal standards. However, this is football, and it does not obey normal standards. Manchester United recently offered Wayne Rooney £300,000 a week. Wimbledon’s previous incarnation used to share a league with Man U, and beat them seven times. But the Wimbledon fans’ year and a half’s worth of hard-raised cash wouldn’t cover Rooney’s salary for two days, and the result should they meet would never be in doubt.

And Chelsea make Manchester United look positively frugal. In his first decade as owner of Chelsea, Roman Abramovich dropped more than £700 million on players. And that’s nothing compared to Manchester City, whose Qatari owners have spent almost a billion pounds turning their plaything into title contenders.

“It makes it virtually impossible to compete. The other huge challenge we face is finding a consensus in a democracy,” said McNay, the record producer and club vice-president.

Wimbledon has shaken off many of its insurgent roots in its progression from pressure group to League club. It took over Couper’s rebel programme. It learned to sack managers. It agonised and rejected a take-over offer from an Irish property magnate (a decision that post-crisis looks as sensible as it then looked idealistic). It has decided what it is: a democratic football club for people who just want to watch football, but one that wants to win as well. But that means it has to compete against clubs owned by oligarchs, who can sack a manager on a whim, and buy a player in the way the rest of us might buy a sandwich.

“Getting a consensus in decisions is not easy, and getting change is not easy. It is far easier if you own your own business. People from very different backgrounds, with different knowledge, different experiences, that’s been challenging,” said McNay.

Stewart, who was AFC Wimbledon’s first chairman, and Couper, who edited its programme, no longer have roles in the club. They remain passionate fans, but admit they were perhaps better suited to protesting than governing. The club’s focus is now on the business people like Heller, who is trying to bring in the money needed to make an effort to go up.

Although the club’s fund-raising is hamstrung by not being able to sell out to a benefactor, its democratic structure has helped it find volunteers to do everything from manning the turnstiles to flipping the burgers. And it has attracted sponsors, too. The first was Sports Interactive, the team behind the enormously successful computer game Championship Manager (now called Football Manager).

Since their computer game involves players taking over a team, managing it themselves, buying players within a strict budget and trying to win promotion, the synergy with AFC Wimbledon was obvious. Alex Bell, accounts manager at Sports Interactive, was having lunch at the neighbouring table before the Exeter game, and explained to me how the company had been involved from the very beginning.

“Our managing director called up Ivor and said he wanted to get involved,” he told me.

“I am now a Wimbledon fan, I wasn’t when we started. There were no Wimbledon fans at our company but it seemed like something that, if we could help we should… It’s something that grabs you. It really is. Obviously, I’m biased now I’m a fan, but what was going on was a crime against the fans on a pretext of making money. It was very wrong indeed.”

The weather was filthy for the Wimbledon-Exeter game. It started gusty and cold, and the wind picked up as the game wore on. With low stands at the Kingsmeadow stadium there was little protection from the elements, and we shivered as we waited for kick-off.

Wimbledon started terribly. The players looked like they barely knew each other and Exeter quickly scored to go 1-0 up.

Tony Bailey, the 77-year-old fan beside me, sank down in his seat, crossed his arms and scowled. The Wimbledon players gained more cohesion as the half wore on and the fans found their voice: “we love you, Wombles, we do”; “AAAAA FC, Wimbledonnnn”; and the old sung favourite “I can’t help falling in love with you”. Wimbledon equalised and the fans roared.

Among the banners around the pitch were some advertising Nerdfighteria, fruit of the club’s latest sponsorship, a hook-up with the American author John Green. Green, who writes young adult fiction and is one of the two brothers behind the hugely popular youtube venture vlogbrothers (slogan: “raising nerdy to the power of awesome”), has fallen in love with AFC Wimbledon. In one of his youtube channels, he commentates over footage of himself playing football on the computer, and AFC Wimbledon is his new chosen side.

I THINK I’M THE FIRST NOVELIST TO SPONSOR A PROFESSIONAL FOOTBALL SQUAD

He sings songs for his players when they score, and the rest of the time he discusses art, literature and other things that take his fancy. All revenue from the videos, which can attract more than 80,000 views and are extremely entertaining, goes to the real-life Wimbledon.

“I think I’m the first novelist to sponsor a professional football squad. We are really excited about it. The community that has grown up around our video blogs is very much a community that believes in a DIY aesthetic and the values are very much in line with AFC Wimbledon,” he told BBC London.

Nerds at their computer screens and football fans on the terraces are not communities with much natural overlap, but AFC Wimbledon pulls everyone in.

In the second half, Wimbledon was playing into the strengthening wind, and Exeter started to take control. Kicks from Wimbledon’s goalkeeper lost their momentum in mid-air and the ball would sometimes be going backwards by the time it reached the ground. Exeter crowded forward, their phalanx of fans on the terraces opposite me shouting them on. Then, with 73 minutes gone, against the run of play, Jack Midson scored for Wimbledon. The crowd erupted.

I asked Bailey, my 77-year-old neighbour, if he wouldn’t prefer to be warm watching the megastars at Arsenal, Spurs, or one of London’s other Premier League sides, rather than shivering in the hail.

“I used to go to Fulham, Chelsea, all that as well, but I don’t go anymore because it’s too bloody expensive. Anyway, it’s more friendly here, and in a small club like this you don’t get any violence,” he said, his eyes fixed on the Exeter players as they searched for an equaliser.

And would he like Wimbledon to get back to the top flight, even if it meant selling out to an oligarch?

“I’d sooner stay like this, owned by the fans,” he said.

It was dark by now, the floodlights were on, and great curtains of hail danced and twisted in the night sky. The stand shook beneath me. Wimbledon held on for the victory, their first in five games. Joy was all around and lightning flashed on the horizon as the trains rolled by.

As I write, Wimbledon are ninth in their division, a safe distance from the danger zone at the bottom, where one club will drop out of the League at the end of the season. It’s too early to say that their place is secure, but if they can hold on, they are a step closer to securing their position in the top flight.

So, what’s next, I asked Couper. Well, there is the continuing irritation that the club that used to be theirs – now called MK Dons (MK from Milton Keynes, Dons from Wimbledon) – not only still exists, but is a division above them.

“The ideal scenario would be if we got promoted and they got relegated so we do not have to play each other,” said Couper, smiling at the thought. (The two sides have played once, in the FA Cup in 2012, leading to much soul-searching from the Wimbledon fans over whether to attend. Some did, some didn’t; Wimbledon lost 2-1 on a heart-breaking back heel delivered in stoppage time.)

And is Wimbledon the future? Is the future of football to be run by the fans, and to escape the tyranny of rich owners in the boardrooms and over-paid primadonnas on the pitch?

“I’ve been to see Arsenal at the Emirates, and you are a customer. You might as well go to the theatre. It’s great, but how many people are season ticket holders for Phantom Of The Opera? With Arsenal, I suspect their management look at the seats and they do not see individuals, they just see 50 quid. It’s irrelevant for them if that person is an architect or a writer or someone who’s willing to spend time knocking on doors, but not for us,” he said.

Couper had to hurry back to Amnesty International, to field the calls and emails from all over the world that had built up his absence. But he would clearly have been happy to keep chatting about Wimbledon all afternoon.