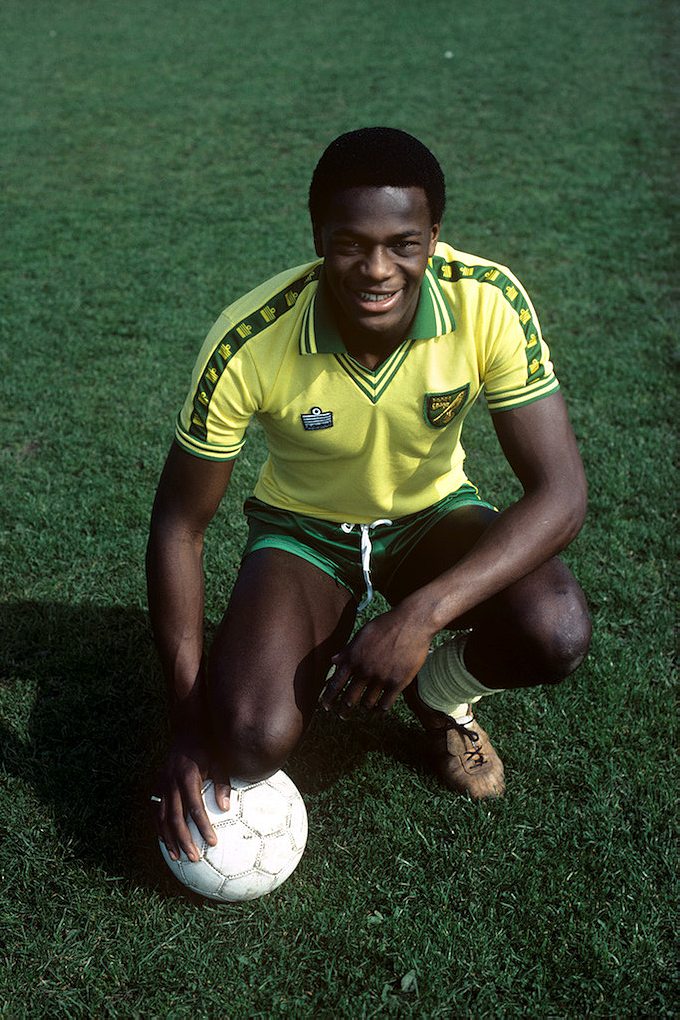

Justin Fashanu was a rugged English striker and the first black soccer player to be traded for a million pounds. He was also openly gay.

On the morning of May 3, 1998, Justin Fashanu was found dead. He had hung himself in a disused garage lock in Shoreditch, East London, about a mile away from where he had been born in Hackney, 37 years prior. He had spent the hour before his death at the Chariots Roman Spa, a local gay sauna. His last words, in a suicide note, were “I hope the Jesus I love welcomes me home.”

And so ended the life of the first openly gay professional soccer player.

When Michael Sam made his recent courageous announcement, there was a sense of him standing on the shoulders of giants, retired gay US sports stars like Billy Bean, Wade Davis, and Dave Kopay. Justin Fashanu had no such mentors. Sam’s coming out was (largely) met with sympathy in the media. His was a highly choreographed and meticulous outing with agents, publicists and America’s premier print publications and broadcasters all onside. As he told the sympathetic New York Times, “I just wanted to own my own truth.” When Justin Fashanu came out in 1990, in a bigoted and bruising England that was staggering through the end of a decade of rule by Margaret Thatcher, Fashanu had no such allies in public relations or the English media. When threatened with an outing, Justin accepted a tabloid newspaper’s meager payoff and gave them all the tawdry gossip they wanted to hear. The truth did not matter. Justin was the first canary in the coalmine, the first to come out of the closet in a toxic era. He was never going to own his own truth.

Justin Fashanu was born in inner-city London, the son of a Nigerian barrister and Guyanese nurse. An absconding father and a mother unable to make ends meet led to Justin and his younger brother, John, being sent to Barnardo’s, a charitable British institution that prepares children for fostering and adoption. Justin was six years old when empty nesters Alf and Betty Jackson of Attleborough, in the pastoral county of Norfolk, about 120 miles northeast of London, agreed to foster the Fashanu brothers.

Justin had been a promising teenage boxer, twice a British Amateur Junior Heavyweight finalist when aged 14 and 15. He could have been a contender, but for the persistence of a scout at local soccer club, Norwich City—a quintessential small town team nicknamed the Canaries–who persuaded him he could have a career in soccer. Justin was signed as an apprentice and spent his school holidays honing his skills with the pros.

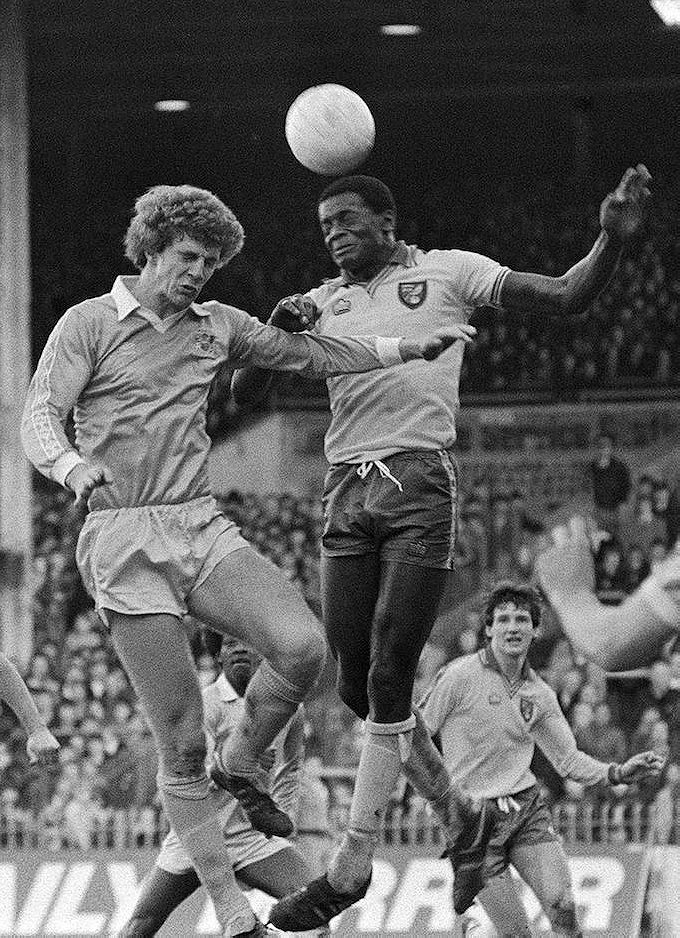

Fashanu was a raw 17-year-old rookie when he debuted for Norwich City on January 13, 1979. The opponents were West Bromwich Albion, a club from the industrial midlands of England, known as “the Black Country” — a colloquial term coined from the soot of industry, but which could have also applied to the fact that WBA were then a race trailblazer in English soccer with the prominence of not just one, but three regular black starters. West Brom’s black players were subject to racist abuse at most every ground they graced. A particularly notorious example is now retained in the annals of YouTube, when West Brom’s black players were roundly booed with most every significant touch in their thrilling 5-3 demolition of Manchester United at Old Trafford that same season.

The broadcasting of soccer in England was then largely limited to two highlight shows a week, so most hooligans and racists were denied their fifteen minutes of infamy. It was this limited terrestrial coverage that would, however, catapult Justin Fashanu into the consciousness of the English nation.

Norwich were hosting Champions, Liverpool, in Fashanu’s second professional season. The cameras were at Carrow Road, the Canaries’ home stadium, a cosy and quaint structure, despite all the concrete and asymmetric, corrugated canopies. The expectation was for ritual slaughter, so often the norm when Liverpool rolled into town. Liverpool were then in the middle of an unprecedented stretch of European domination, that saw them conquer the continent four times in seven years. The men from Merseyside were like a machine scorching the earth and taking no prisoners. Scoring goals against Liverpool was a largely futile exercise in those days. But Justin resisted. With Liverpool 3-2 up and heading for victory on a dreadful pitch, the young forward smashed an unstoppable volley into Liverpool’s net from 25 yards to level the scores at 3-3.

Journalist and Norwich City fanatic Juliet Jacques, described Justin’s phenomenal goal best in her essay, “The Meaning of the Goal.”

“It was a brilliant piece of team play with a breath-taking individual finish… With the impudence of youth, [Fashanu] flicked the ball up with his right foot, turned, and volleyed it into the tiny space between [Liverpool keeper] Ray Clemence’s head and the post. The strike was perfect – as so was the celebration. There was a split second while the crowd, and the commentator, processed its brilliance: as the fans roared, Fashanu stood alone, one finger raised to the skies as if to announce his genius. Norwich eventually lost 5-3, but the goal overshadowed the result: it made the perfect television image, coming as a generation of black footballers were breaking through at England’s top level, leaving Fashanu poised to become their leading light.”

Fashanu’s goal, which claimed the BBC’s ‘Goal of the Season’ accolade, was no fluke. He scored 35 goals in 90 appearances for Norwich City over the course of three seasons. Those were prime time stats, particularly for such a young player, and marked him among the most promising talents in England. His performances at club level were rewarded with England under-21 honors, and he scored 5 times in 11 under-21 international appearances between 1980 and 1982. The news clippings and rare video evidence of the time reflect the trappings of a classic Number Nine. Justin holding off challenges; Justin scything through defenses; Justin crashing shots into the net; Justin out-jumping defenders and bulleting headers. Justin was just doing it before Just do it was invented.

It was this accomplished record that persuaded Nottingham Forest to make Fashanu the first black soccer player to be traded for a million pounds. Nottingham Forest were big-time then, the only team to present a serious challenge to Liverpool in English and European competition. Led by their redoubtable manager Brian Clough, known as Old Big Head and recently depicted by the actor Michael Sheen in the biopic The Damned United, Forest had been champions of Europe in 1979 and again in 1980. Fashanu’s move was a headline story. He was the not the first black player in Britain, but he was the first to be sought by a big club. It was a seminal moment for black Britain.

Throughout the 1980s, black players in Britain were relentlessly subjected to racist abuse from the terraces. Monkey chants, vile epithets and bananas hurled on to the field of play were the choice weapons of humiliation. It is impossible to pinpoint the moment such behavior became unfashionable, but a combination of black players making the grade for the biggest clubs and being chosen to represent the English national team, mollified the mob.

IT SIMPLY WOULD NOT HAVE OCCURRED TO MOST FOLLOWERS OF THE GAME THAT A SOCCER PLAYER COULD ACTUALLY BE GAY

It was a muddy transition. A friend who followed Manchester United to all corners of the country in the 1980’s once recalled how, on a visit to St. James Park (Newcastle United’s home stadium) in 1985, the Magpies’ Tony Cunningham was a target of racist abuse from elements of his own home crowd. The minority of vocal racists that were littered among the Manchester United away support apparently found this both humorous and vexing: Booing the opposition’s black players had once been their job. The same Manchester United crowd that only a few years earlier had booed West Brom’s black players were now inventing jangles to cheer on their own black players. Times were changing, but slowly.

Gay slurs at football matches were also common in this era. These days there is even a Proud Canaries fan club of gay Norwich City supporters. But in Fashanu’s heyday, terms such as “faggot”, “fairy” and “tart” were de rigueur, though they were hurled into the miasma of foul language and other discriminatory discourse that typified English soccer crowds, and most spheres of public culture, at the time. It simply would not have occurred to most followers of the game that a soccer player could actually be gay, let alone be built a like heavyweight boxer.

It was into this primitive social flux that Justin Fashanu flexed his muscles for his first full season with Nottingham Forest. It was to prove an unmitigated disaster. Justin failed to live up to expectations, scoring on only three occasions in 32 appearances in his first and only full season for the former European champions. There are no spectacular goals on his limited highlight reel from that season, but instead a couple of outrageous miscues, with Justin looking chaotic, uncomfortable and seemingly incapable of a meaningful relationship with a football. Fifteen months after his marquee arrival, Justin was traded at a massive loss to cross-town rivals, Notts County, for a fraction of the famous fee Forest had paid Norwich City a year or so earlier.

Forest’s boss Brian Clough wrote in his 1994 autobiography that Fashanu’s ‘goal of the season’ against Liverpool back in 1979 had “conned him out a million pounds”.

Yet the sale of Fashanu for an absurd fraction of his original fee, despite his first season failings, made no financial sense. Was Fashanu being made a scapegoat, an example to the others of the ruthlessness of the sport? Possibly. But surely Nottingham Forest’s catastrophic season could not completely be blamed on the poor form of Justin Fashanu. There were ten other players in Clough’s regular first XI that finished 12th in the 1981-82 season. Yet only Fashanu was shipped out in the off-season fire sale.

Rumours of Fashanu frequenting gay bars in Nottingham rattled Clough. In his autobiography, Clough recounts confronting Fashanu about the whispers, “’Where do you go if you want a loaf of bread?’ I asked him. ‘ A baker’s, I suppose.’ Where do you go if you want a leg of lamb?’ ‘A butcher’s.’ ‘So why do you keep going to that bloody poof’s club?’” Fashanu’s private life was now a matter of in-house ridicule. He was facing the prospect of both barrels from his employers and the crowds: racism and homophobia.

Justin turned to Jesus. A couple of minor car crashes had the owner of his local car dealership suggesting he join the “Assembly of God” congregation. Players pointing to the sky and giving the Most High assists for their goals was unheard of in English soccer then, though Justin never had the chance to link up with the Lord in front of goal. His spirituality was tackled at training when he brought a born-again member of the church to the City Ground, Nottingham’s Forest stadium. This enraged Clough, who reportedly yelled, “the religious bloke has got to go,” before ordering the local police to have Fashanu and his biblical consultant ejected.

On New Year’s Eve, 1983, early in his career at Notts County, Justin suffered a major knee injury. It would keep him on the fringes of top tier football for the rest of his career. Other black footballers would soon replace him in the headlines. England’s John Barnes, Ireland’s Paul McGrath, and his own brother, John, were playing international football and winning trophies.

Meanwhile, Justin was devoting much of his finances to knee surgery and rehabilitation in the United States. A subsequent trade to Brighton and Hove Albion in 1985 failed to rejuvenate his career and only served to aggravate his knee injury. Once tipped for the very top of the world game, Justin would spend the next three seasons floating between North American soccer clubs such as the Los Angeles Heat and Edmonton Brickmen and English clubs willing to flirt with him for an appearance or two.

It was in this environment—starved of success and financially constrained by the costs of numerous knee procedures, rumoured to have cost upwards of £200,000—that Justin became a target for the notorious English tabloid press. With rumors he was soon to be publicly exposed as gay, Justin arranged for his agent to negotiate an exclusive with The Sun, the English tabloid with the widest circulation and biggest appetite for unsubstantiated, malignant gossip (as the families of Liverpool supporters who perished at Hillsborough discovered in 1989), for a five-figure sum. Fashanu later explained his choice noting, “papers like The Sun are the ones that football fans read. If I had gone with a serious paper then The Sun would have hounded me for the rest of my life.” Justin proved an unusually forthcoming source. He didn’t just come out, he also rattled off a list of high-profile sexual partners, from Members of Parliament to well-known soap stars. That Justin lied to The Sun about many such exploits was merely feed for further copy. This was just four years after the paper had splashed the famous, and entirely fictitious, front-page headline “Freddie Starr Ate My Hamster,” and eight years after it reported the sinking of an Argentine naval ship by British forces with the single word “Gotcha.” Justin saw the gutter tabloid as the gift that could keep on giving.

AS JUSTIN WAS CAST OUT, MARGINALIZED AND FORGOTTEN, [HIS BROTHER] JOHN WAS EMBRACED

Justin would remain just fit enough for a series of swan songs in the lower leagues of professional football in England, Scotland, Sweden, the USA and New Zealand in the 1990s. His goal-to-game ratios was as good as they were when he was once a proud canary at Norwich. Justin may have been portrayed as a novelty signing at places like Torquay United, but he did precisely what he was paid for: lead the line and scored goals, 15 in 41 appearances for Torquay between 1991 and 1993.

He made the switch to coaching in the late 1990s and took an opportunity with the Maryland Mania franchise. It was there in March 1998 that he was accused of sexual assault by a 17-year-old male. The age of consent was 16, but homosexual acts were illegal in Maryland at the time. Justin denied the accusations and fled the country, fearing he would not get a fair trial if arrested. Two months later, he was found hanging in a deserted London garage lock up. A suicide note claimed his innocence, claiming whatever sex there had been was consensual.

The tragedy of Justin Fashanu is paralleled by the rise of his younger brother John. The two young brothers taken into foster care in the mid 1960s were to see their lives take radically different courses through late twentieth century Britain. As Justin was cast out, marginalized and forgotten, John was embraced.

A rugged striker like Justin, but never as technically gifted, the highlight of John’s career came in 1988 when he was part of the famous Wimbledon team known as the “crazy gang” which won the FA Cup final against Liverpool. On retirement he embarked on a successful career in Saturday night television. He hosted the popular game show “Gladiators” and endeared himself to viewers as “Fash,” wearing colorful outfits and popularizing his catchphrase “Awooga!” He is now a well-connected businessman in Nigeria, where he hosts the local version of Deal or No Deal.

Nigeria is, of course, the country that recently criminalized homosexualitywith penalties of up to 14 years in prison. Nigerian novelist Teju Cole told me it would be “impossible” for a football player to come out and that “no prominent Nigerian-based figure [has] come out against the anti-gay law.” But even before John was a Nigerian celebrity, when Justin was still alive, John had used The Voice, Britain’s only black national weekly newspaper, as a platform to express incredulity with Justin’s decision to come out. The exclusive interview was headlined “John Fashanu: My gay brother is an outcast.” The Voice itself went further saying the manner in which Justin came out in the The Sun was “an affront to the black community… damaging… pathetic… and unforgivable.” Justin felt the rejection of his brother and his own community deeply, according to confidant and friend, gay activist Peter Tatchell.

Two years after his brother’s suicide, John appeared on an English chat-show, and recounted a phone call he’d received just prior to Justin’s death. “Just before he committed suicide, there was a telephone call to my mobile phone that night and the person wouldn’t speak. I could hear breathing, I could feel that it was somebody from my family. I could feel that it was Justin, but I didn’t reach out. I just put the phone down and thought: “Oh, it’s him again”. And the next day he committed suicide.”

In 2012, John told the BBC he believed his brother “wasn’t really gay”, but was merely “seeking attention.”

“I’m not homophobic and I never had been, but at the time I was certainly cross with my brother. I sleep at night wondering all the time, could I have done more and I keep coming up with the answer, yes I could have done more. Does that console me? No. We’ve cried for nearly two decades for Justin, it’s enough.”

John’s daughter Amal Fashanu, for her part, presented a BBC documentary, “Britain’s Gay Footballers”, in 2013, which was an even-handed account not just of the familial discord, but—more importantly for her—Justin’s broader legacy as a footballer and a person. “Justin was the first Million Pound black footballer,” she told me when I spoke with her recently, “and before anything else he should be remembered for being one of the most skillful football players of his time.”