The Taiwan firewater that warms frosty relations

The Taiwan firewater that warms frosty relations

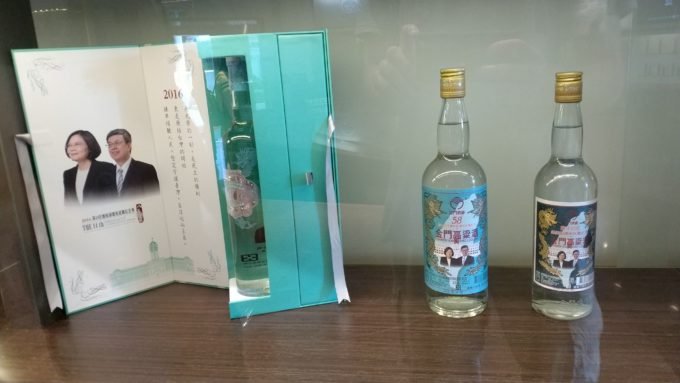

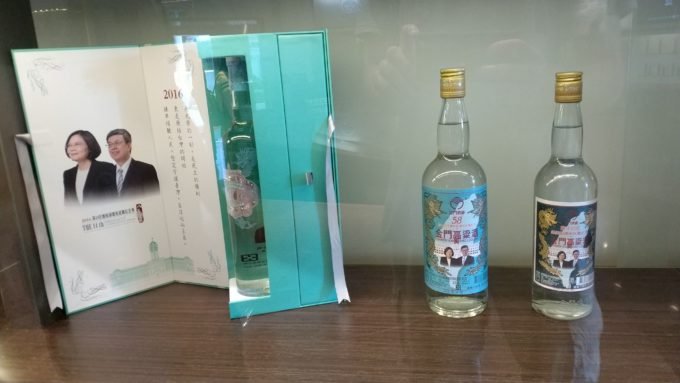

Kinmen Kaoliang in Taiwan

Kinmen gets plenty of attention as a barometer of Taiwan-China relations. Naturally, it cares far more about its sorghum wine.

Kinmen Island, a Taiwanese outpost 3.7 miles from the shores of China, has long served as a measure of cross-strait relations. As enmity between the two neighbors has begun to boil over, I flew out to see what was up.

It wasn’t too surprising to find Kinmenese bonding not over political leanings, but over their true pride and joy: Kinmen Kaoliang, a sorghum-based firewater commonly sold at 38 percent or 58 percent ABV, and a fixture in any self-respecting household.

Kaoliang, like all baijiu, distinguishes itself by its visceral impact. While some Chinese baijiu scorches from sinus to stomach, “58” Kaoliang is more subtle, packing just enough punch to jolt you out of the island’s sleepy stasis into a jovial mood. After three or four, your spirits are golden.

According to local lore, Cold War soldiers fell in love with the stuff as it warmed them up on foggy, windswept nights hiding in bunkers from relentless Chinese shelling. When the wartime general Hu Lian dubbed Kaoliang as his go-to spirit, Kinmenese turned to sorghum farming, and the Republic of China was swept with Kaoliang fever.

At Kinmen Kaoliang’s sprawling central distillery, a grinning employee happily offered up thimble-sized shots and explained how the local libation plays the role of social adhesive. The state-run company funds social programs that are the envy of the rest of Taiwan: free bus rides, subsidized scholarships and pensions, and most famously, duty-free Kaoliang. Three times a year, on national holidays, residents over 20 can buy up to a dozen tax-free bottles and sell it for a profit—or swill it.

And who can say no to that? Kinmen’s population is growing around 4 percent annually, and Chinese tourists are flooding the island in record numbers, doubtlessly spurred on by Kinmen’s smooth-as-water adaptation of baijiu. Nowadays, Kaoliang is a fixture in international competitions, giving this sleepy island of about 160,000 an outsized presence on both the spirit-connoisseur and geopolitical landscapes.

When Taiwan-China relations cool, Kaoliang is there to keep things warm. The government here just opened a water pipeline to the mainland, displeasing skeptical national leaders. But despite the disagreements, Kaoliang stays out of the crossfire. When Taiwan’s vice president welcomes foreign leaders in a bid to hang onto Taiwan’s 17 remaining diplomatic allies, he’s known to break out the Kinmen Kaoliang.

Kinmen officials say the pipeline was sorely needed. Just before its activation, Kinmen found itself with less than four months of fresh water remaining. That’s bad news for Kaoliang production, as any adherent will tell you: Kinmen Kaoliang is distinguished by its fresh water, said to mix with the sea’s aroma. This potion is truly home-brewed.

One wonders what will become of Kaoliang post-pipeline. Will it be produced with (gasp!) Chinese water? The cynic may see that as another step of China’s silent incursion onto the island they once shelled. But the motley crew of Taiwanese and Chinese students I drank with that night had little time for such concerns. Everyone shared a common bond—and there was plenty more of that on the shelf.

Up Next

Hanging Ten in Taiwan

A Scottish‑Style Whisky With Indian Characteristics

In tropical Goa, a master distiller takes on single-malt.

A Simpler Time When Watery Beer Would Do

I had wandered 10th-century temples and learned how to tell real jade from fake, but I had yet to find a decent drink.

Reinventing the Wheel

Monarch Tractor has recently launched its first line of electric tractors with its groundbreaking MK-V model – the world’s first full-electric, driver-optional, data-collecting smart tractor. Its CEO hopes the company is going to revolutionize the future of farming.

Simon Shuster: Reporting on Russia in the Trump era

Moscow-born foreign correspondent Simon Shuster on reporting the world in the Trump era, Russian-American drinking styles, and life in Berlin.