The food of Manila reflects a predilection for welcoming outsiders. Welcome to the salu-salo, the fiesta, the party: here are the dishes to watch for.

It’s happened to me in numerous airport transit areas, in a hotel lobby in Rome, at the dentist in Singapore, in a store in Tokyo—anytime and anyplace that a fellow Filipino abroad catches the accent and starts up a chat. It’s always the same question, the essential one for the Filipino diaspora: “Saan ka sa atin?” Which part of the homeland are you from?

The question is one part friendliness, one part excuse to speak Tagalog, one part shortcut to understand your compatriot. The Ilocanos of the northern flatlands are a thrifty lot with a salt-heavy cuisine. Pampagueños have a reputation for complex palates. The Negrense, from sugarcane country, like things a little sweeter. Cebuanos know their way around lechon. And if you’re from Manila, like me? Then really you’re from somewhere else.

My parents are originally from Bicol, a region on the eastern flank of the Philippines known for its coconut-based stews spiked with a tiny, fiery chili called siling labuyo. My mother’s cooking combined Bicolano specialties with child-friendly standards like fried lumpia (spring rolls) and embutido (meatloaf wrapped in pork caul), always served with white rice and a dipping sauce of banana ketchup.

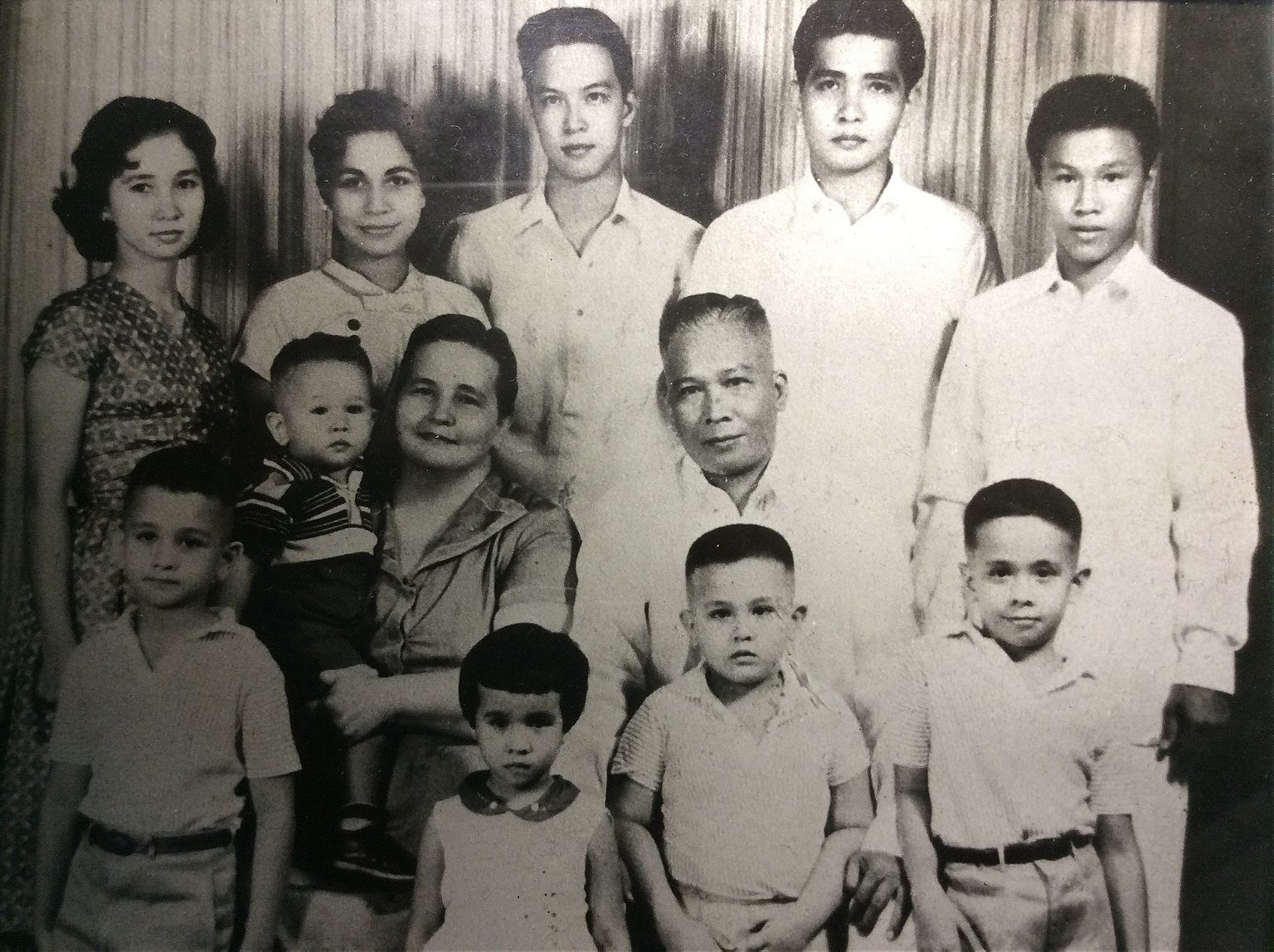

My father’s mother, Lola Billie—a mestiza born to an American father and Spanish mother—specialized in hamburgers, bound with a glut of eggs and flattened in the pan to crisp their edges. Several cousins lived in Binondo, Manila’s Chinatown, where we would visit them several times a year for lauriat dinners, multi-course meals organized for special occasions by my paternal grandfather, Lolo Ramon. He was Philippine-born Chinese. As a kid I simply took for granted that a few times a year one sat at a round table with obscure relatives to eat abalone and pancit (noodles) using chopsticks.

Looking at my cousins and me today, one wouldn’t necessarily guess that we’re related. Some, like my sister, look decidedly Chinese, while others inherited the height or skintone of our Spanish (or maybe American) ancestors. Many, like me, simply look Filipino, clearly Malay, but with features that dovetail with those of other parts of Southeast Asian, Southern China, or the southernmost tip of Taiwan. We are one family, Manila born and bred, decanted and remixed so many times that our hybrid nature is our very identity.

As go Manila’s natives, so goes its cuisine. The food of Manila reflects a predilection for welcoming outsiders, for taking them in and helping them integrate, for better or for worse. Welcome to the salu-salo, the fiesta, the party. Here are the dishes to watch for.

Adobo at Purple Yam (restaurant in Malate or kiosk in Estancia Mall, Capitol Commons)

Historians point to the Tagalog people, Austronesians who migrated from the Pacific Islands and established settlements along Manila Bay and the banks of the Pasig River, as the first residents of what we now call Manila. And no dish in the Filipino arsenal is as emblematic of their cooking as adobo: a braise of vinegar, soy sauce, garlic, black peppercorns, and bay leaves.

The modern name for the dish originates with the Spanish, who, in need of a Latin vocabulary to codify their new colony, referred to the dish as adobo de los naturales, literally “the marinade of the natives.” And native it is. Every island, province, town, and household has its own recipe. Adobo is the national umbilical cord to our earliest forebears. No matter what external influences work their way into our culture, adobo will ground us.

The earliest Filipinos would have used coconut vinegar, cane vinegar, or rice vinegar to cook and preserve their food. Salt, native to the islands, was later replaced or enhanced with soy sauce, introduced by Chinese traders. Standard adobo is made with chicken or pork, but anything can be adobo’d—squid, beef, quail, shrimp, kangkong (water spinach), catfish, tanigue (mackarel), frog legs, crickets, banana flowers, bamboo shoots. Wherever you’re from, and whatever your taste, the best adobo is almost always your mother’s.

Amy Besa, owner of Purple Yam in Brooklyn and Manila, also a self-described Manileña, makes her adobo with apple cider vinegar because that’s what was available in her city supermarkets growing up. A recipe from her book Memories of Philippine Kitchens uses baby back ribs and replaces the peppercorns with tellicherry peppers. She shared her recipe with the New York Times, where it maintains a perfect five-star rating from hundreds of homesick Filipinos.

Pancit Mami at Masuki Mami House (Benavidez Street, Binondo)

When Chinese traders first arrived on the islands in the 9th century, they brought with them an array of noodle dishes from the homeland that have, over the years, come to be known collectively as pancit. The word comes from the phrase pian i sit, meaning “convenient food” in the Hokkien dialect spoken in Fujian. Hawkers eventually set up panciterias, Manila’s first restaurants, with Binondo as their epicenter. It is the world’s oldest Chinatown, established in 1594 when the Spanish Governor granted land to immigrant Chinese merchants who had converted to Catholicism. For 400 years, Binondo was the economic center of Manila.

Over the centuries, pancit spread throughout the islands, taking on the distinct character of each place. Made with boiled egg noodles and topped with shellfish, it’s called pancit malabon, named for the fishing town north of Manila. With thin rice noodles, sautéed and tossed with pork, chicken, shrimp, vegetables, hard-boiled eggs, and chicharon, it’s called pancit bihon, from the Hokkien term bee hoon meaning rice vermicelli. Take the same noodles, cook them in boiling water, toss in a shrimp sauce with all the toppings, add achuete powder for color, and it’s pancit palabok. (“Palabok” in Tagalog means “added flavor.”) One can go from north to south on the Philippine map and match each province to its pancit, as food historian Claude Tayag has done, calling out pancit canton, pancit sotanghon, pancit palabok, pancit habhab, pancit langlang, batchoy, udong, miki, molo, lomi.

Manila’s homegrown variation, invented in the 1920s by a Chinese immigrant called Ma Mon Luk, is called pancit mami. A faithful version of the dish—wheat flour noodles served in a clear chicken broth, topped with chicken, beef or pork, and paired with siopao (steamed pork buns)—is still served by his great-grandchildren at Masuki Mami Restaurant in Binondo.

Ensaymada and tsokolate at Mary Grace Café

Spain operated the Manila Galleon, a spectacularly expensive trading ship that plied the seas between Manila and Acapulco once annually, for 250 years. The galleon carried silk, porcelain, gold, and other goods from China, exchanging them for Mexican silver and Spanish foodstuffs that, due to their scarcity and cost, were reserved for festive occasions.

Get yourself invited to a fiesta in the Philippines (it’s not difficult, just say you want to try the local food) and you’ll taste lechon (a whole pig stuffed with herbs and roasted on a bamboo spit), paella, and leche flan. The biggest fiesta of all is Christmas. On the radio, DJ’s, as a half-joke, will play Christmas songs on the 1st of September, and Christmas decorations often start going up as early as November, typhoon season be damned.

This all culminates in Noche Buena, the meal served at midnight on Christmas Eve, a tradition passed on by the Spanish. Before many of my family members dispersed to America and Canada and Singapore, it was normal for forty-odd people to come together each year, descending on a table laden with baked ham, queso de bola (bowling-ball sized globes of Dutch Edam cheese wrapped in shiny red foil), and ensaymada, a sugary brioche based on a bread from Mallorca.

If you visit at any other time of the year, you can get a whiff of festive food by ordering ensaymada at Mary Grace Café. The owner perfected her version of the pastry in 1994 and it’s now available daily in major malls throughout the city. Her ensaymada has a generous cover of shredded Edam cheese, spends a minute under the grill, and is best paired with a cup of viscous hot chocolate.

Gambas al ajillo and San Miguel Beer at Dencio’s Grill

Drinking culture has long existed throughout the archipelago. Farmers in the Tagalog provinces south of Manila celebrate rice harvests by pouring shots of lambanog, a variety of moonshine distilled from coconut flowers. Manileños celebrate the end of the workday by flocking to nearby watering holes, sometimes as a strategy for avoiding the city’s hellish rush hour traffic.

Reliably, on most bar menus, there is pica-pica, the Filipino answer to tapas. Unlike the custom in Madrid of having a few bites standing at the bar, in Manila we find a table and hunker down for the evening. You can get gambas al ajillo— plump shrimp and golden shards of garlic served on a sizzling plate with plenty of crusty bread to soak up the olive oil— or go local with a plate of sisig, grilled pork face and ears sautéed in our own classic mirepoix of ginger, garlic, chili and onions then seasoned with soy sauce, calamansi, and coconut vinegar. If you want to turn tapas into dinner, just ask for a side of rice and a fried egg. Proper tapas bars might look at you funny, but the down-home beer houses, like Dencio’s Grill, will readily oblige.

Nothing goes better with bar snacks than a cold bottle of San Miguel Beer. The brewery—Southeast Asia’s first—opened in 1890 shortly after artificial refrigeration made it possible to brew in the tropics. San Miguel gained immediate popularity among European expats, and when American soldiers arrived there was such high demand that the brewery had to shift most of its inventory to Manila. During the American colonial period, the beer was dear, costing half the price of lunch. Today, a bottle of Pale Pilsen is as cheap as bottled water.

Corned beef pan de sal at Kamuning Bakery (or any Starbucks)

In the 1889 Treaty of Paris, which ended the Spanish-American War, a decrepit colonial power sold its last important possession to an emerging one for $20 million. Unfortunately, nobody told the newly established Philippine Revolutionary Government, so the deal that ended one war also launched another: the brief-but-brutal, three-year-long Philippine-American war.

The Philippines became America’s only formal colony. For 35 years the United States worked to shape a fledgling, little-understood nation in its image: government, education, language, urban planning, and, of course, food, particularly processed foods like corned beef and refined wheat flour. The flour, imported in bulk, was cheaper than rice, so places like Kamuning Bakery, which opened in 1939, popped up around Manila to prepare small, airy pan de sal, or salt bread.

Pan de sal is best in the morning, fresh out of a pugon, or wood-burning stove. At our family breakfast table, when I was growing up, my parents dipped their pan de sal in steaming cups of Nescafe, while mine made for perfect fist-sized sandwiches of peanut butter, Cheez Whiz, Spam, sausage links, or corned beef. Though you’ll now find super-sized pan de sal with corned beef at Manila’s branches of Starbucks, it’s still the everyman’s bread. At local bakeries, a roll won’t set you back more than PHP2.50 today (5 cents). Kamuning Bakery warns people if they think the cost of flour might force them to increase prices.

Halo-halo at Milky Way Café

It took not one, but two foreign influences to bring halo-halo into existence. Americans built the country’s first ice plant, Insular Ice and Cold Storage, in 1902, for their troops in the tropics. Ice and ice cream, once luxuries, became more accessible. Japanese immigrants arriving in the 1920s opened shops installed with ice shavers and sold mongo con hielo, shaved ice topped with red beans, sugar, and evaporated milk. This dessert was itself a variation on a Japanese dish called mitsumame, meaning “many beans.” The local palate had been primed.

Take boiled sweet red beans, macapuno (tissue-like coconut flesh), sliced minatamis na saba (saba bananas cooked in a sugar syrup), jackfruit, green jello, nata de coco (jellied coconut water), kaong (palm fruit), and pinipig (puffed rice). Add a layer of shaved ice doused in evaporated milk. Top with a scoop of ube (purple yam) ice cream and a dollop of leche flan. This is halo-halo, our dessert of summer.

The name is Tagalog for “mixed-up.” Every layer reflects a foreign influence: the candied beans are Japanese; the ice, milk, and ice cream are American; leche flan is Spanish. Brought together just so, it’s Filipino. Milky Way Café, a dairy bar that has served the dessert since the 1950s, builds its halo-halo conscientiously, placing ingredients layer by layer into a tall glass: an edible core sample of Filipino history.

Halo-halo is also, simply, an instruction. Dig in with a long spoon, mix everything up, and take the edge off the city heat.

Yumburger at Jollibee (hundreds of branches)

The Americans may have gone, but their hamburgers made a lasting influence on Manila’s food scene, particularly at Tropical Hut, which opened its first fast food counter in 1962 and has been selling burgers ever since. Burger Machine started selling them from food trucks in 1981. But the best example has to be Jollibee, which launched its Yumburger in 1979.

Jollibee founder Tony Tan Caktiong, like many Chinese immigrants before him, made his fortune localizing foreign food. Jollibee started life as an ice cream parlor selling savory snacks on the side, but Tan noticed that customers were polishing off the burgers faster than the desserts. Ever the entrepreneur, Tan refocused his menu on American fast food tailored to the Filipino palate: those Yumburgers slathered with a sweet special sauce; sweet spaghetti topped with sliced hot dogs; and their iconic fried chicken, Chickenjoy.

Filipinos are Canada’s third-largest immigrant community. Last year, when Justin Trudeau attended the ASEAN Summit in Manila, he stepped off the plane and made a beeline for the nearest branch of Jollibee, where he ordered a one-piece Chickenjoy with a strawberry tea float and a side of photo opp.

Even mighty McDonald’s, perhaps the greatest economic and cultural emissary of our one-time colonizers, never managed to close in on Jollibee’s market share. After a decade-long battle, the Golden Arches faced a choice: leave or imitate. When McSpaghetti appeared on their menu, it was clear which path they’d chosen.

Laing sa gata at the Salcedo Weekend Market

Manila’s sprawl started soon after World War II, radiating north, east, and south from the Old City. Immigrants arrived from all over the country: Tagalogs from the surrounding provinces, Kapampangans from the central rice plains, Ilocanos from the north, Bicolanos up from southern Luzon, the Cebuanos, Ilonggos, Negrense, and Mindanawon from the center and south.

By 1975 this sprawl had created 17 cities from open land and was officially renamed Metro Manila. From 1980 to 1990, the population doubled from 5 million to 10. By the 2000s, Nielsen, the TV ratings firm, had coined a new term, Mega Manila, a geographic region representing 25 million people, a quarter of the country’s population.

Arriving in the capital, a domestic immigrant finds no welcoming enclave, but she can always sniff out food from her hometown. My mother, every chance she gets, buys laing sa gata (dried taro leaves in a spicy coconut stew) at the Salcedo Weekend Market. This food market, operating only on Saturdays at Jaime Velasquez Park in Makati’s Salcedo Village, is a one-stop shop for regional Filipino cuisine.

We might pair our laing with whatever looks good on the day, spreading our bounty on a picnic table: bagnet (deep-fried pork belly) from Ilocos, tamales from Pampanga, bacolod chicken inasal (whole chicken marinated in lime, pepper, vinegar, and oil from achuete seeds, roasted over coals), or Ilocos-style empanada (green papaya, mongo beans, crumbled longganisa and a raw egg, packed into a half-moon rice flour wrapper and deep-fried till crisp on the outside).

“Bahay Kubo” at Toyo Eatery

Filipinos have been leaving to work overseas since the first seamen (and slaves) stepped onto a Manila Galleon. Departures increased in the 1970’s and 80’s as English-speaking Filipinos pursued better jobs abroad. Today 11 million are classified as Overseas Filipino Workers; OFW remittances have their own line item in the GDP.

Those who return home are called balikbayan, meaning “a Filipino back in the country after significant time away.” Some of them open restaurants in Manila. At his restaurant Toyo Eatery, Chef Jordy Navarra has created what is, perhaps, the next generation of Filipino food in a dish that he calls Bahay Kubo. It is the name for our traditional bamboo-and-thatch dwelling and for a folk song that every child learns in school. The song names eighteen vegetables that you can plant in your garden; Navarra’s dish is a meditation on what is gastronomically possible with these vegetables, a plant-forward preparation unusual in carnivorous Manila.

Influenced by years working in the kitchens of the U.K.’s The Fat Duck and Hong Kong’s Bo Innovation, Navarra’s Bahay Kubo combines vegetables that have been grilled, roasted, pickled, blended, infused, distilled, and dehydrated. The first time I ate it, my friend and I launched into the familiar tune, cheerily accompanied by our server, as we dug in, searching for our “sitaw, bataw, patani” (string beans, hyacinth beans, lima beans). Nobody was surprised by the singing. It is encoded in our genes and needs no prompting.

Top image: Timi Siytangco