Marwan Hisham and Molly Crabapple discuss their new book and what it was like collaborating when one of them lived in a war zone.

The eastern Syrian city of Raqqa lies in ruin after years of ISIS rule, and an intensive bombing campaign by a US-led coalition. Twenty-nine-year-old Marwan Hisham, now living in Turkey, grew up in Raqqa and lived there during the early days of ISIS’ control of the city. After an interaction on Twitter, artist and writer Molly Crabapple, now thirty-four years old, began using Hisham as a source on articles, which provided a rare insight into life in ISIS-controlled territory. Hisham went to great risks, even taking photos with his cellphone, which Crabapple later based many of her drawings off of. Their most recent collaboration is the book “Brothers of the Gun: A Memoir of the Syrian War,” which details Hisham’s life in Syria, resistance against the Assad regime, and life under ISIS. R&K’s photo editor Cengiz Yar spoke with Marwan and Molly about their work.

[Read: Why Israelis and Palestinians are fighting over a plant in the West Bank]

Cengiz Yar: How did you come up with the idea of collaborating on a book?

Marwan Hisham: Molly and I knew each other through Twitter. I knew about her art and we talked a lot before we did anything together, but then she suggested that I send her photos from Raqqa so she could draw them.

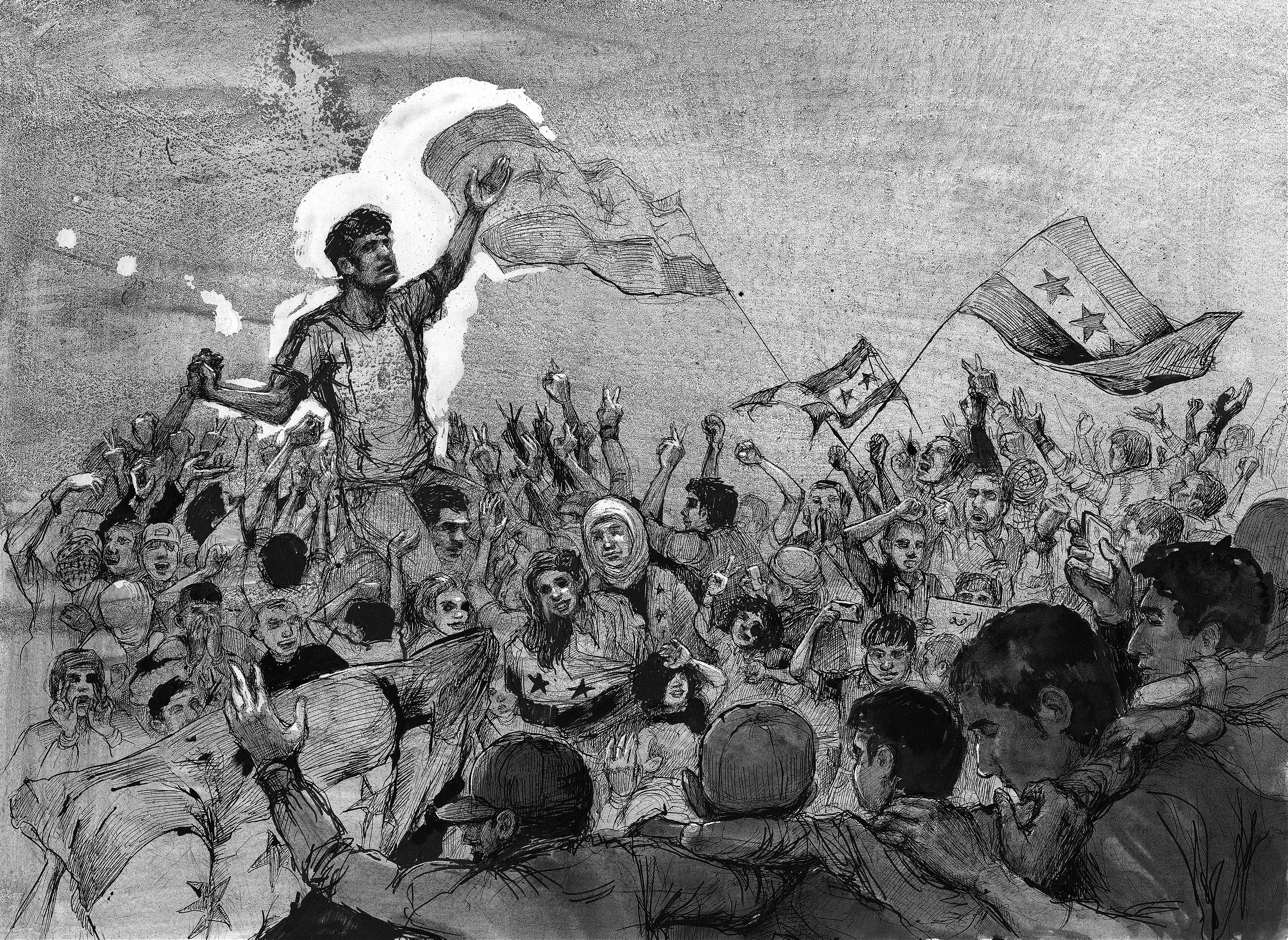

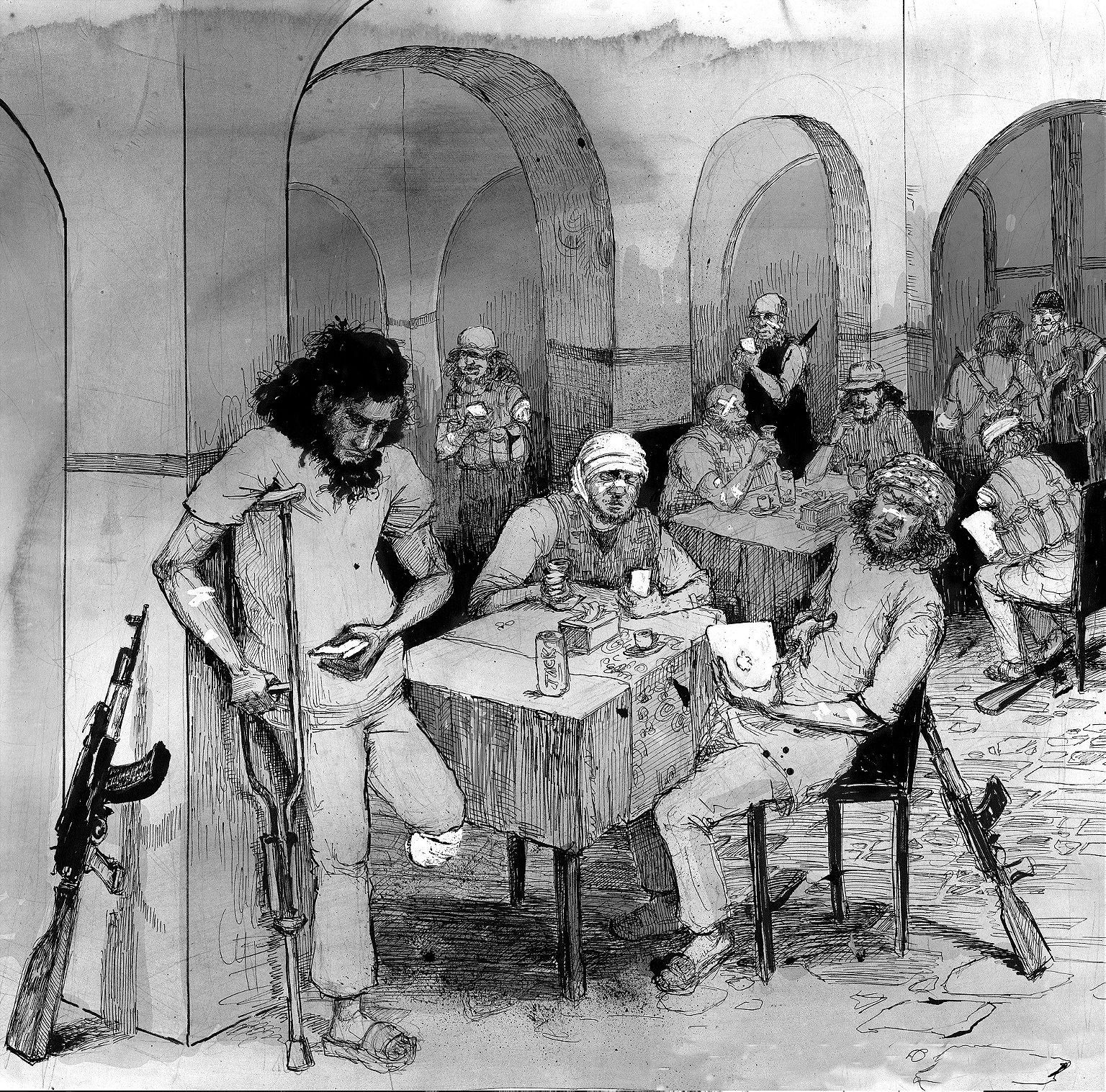

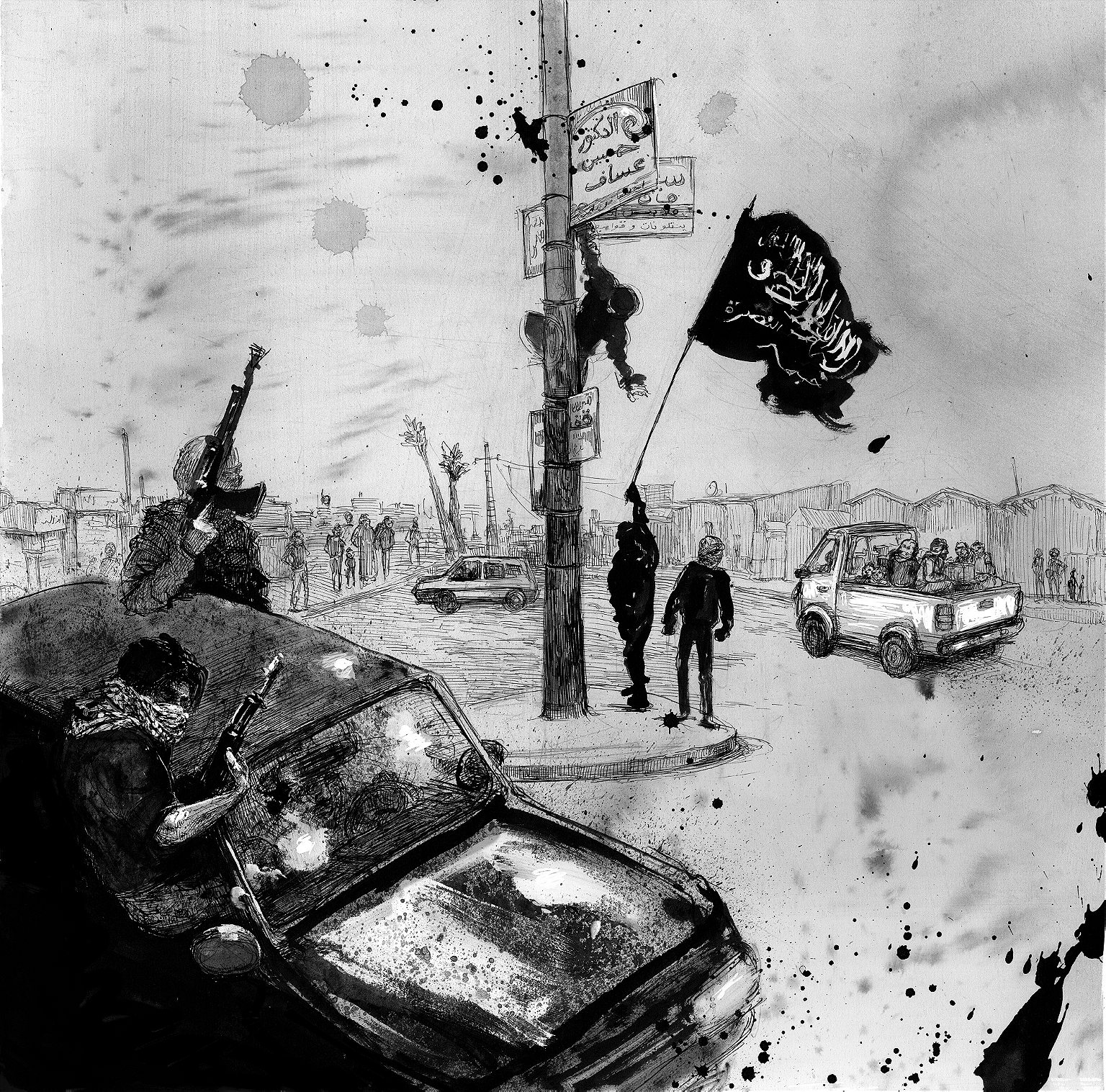

Molly Crabapple: I asked him if he had any photos of the city on his phone, so I could draw illustrations based on them. He didn’t, but he told me he could take some, of course vastly downplaying the danger. A few weeks later he texts me a photo he fucking took inside of an ISIS-controlled hospital and says, “Look I got this photo. No one saw me.” He snuck all around the city taking these photos of stuff that you wouldn’t normally see in mainstream media. Bread lines, kids digging through trash for stuff to sell, or guys sitting outside trying to get wifi. Marwan took pictures of very human things. He was really against cliché war images.

Marwan: We pitched the idea of showing what daily life was like in Raqqa through illustrations to Vanity Fair and they published our story. We did the same thing for Mosul and then Aleppo. Initially, I just wrote short captions for each illustration. For Aleppo, I wrote an article about my experience while I was there as a university student, and how the city changed during the six years I was away. The article and illustrations were well-received. so we thought, Why don’t we expand our collaboration and do a book?

Cengiz: How did you interact with each other while writing this? Was collaborating difficult?

Molly: Marwan and I really pushed each other. It was like a pitched battle. Every single sentence was a negotiation. That’s probably why it seems like the book was written by one person. Marwan art directed the project But I consider them our illustrations, even though he didn’t draw them.

Marwan: Two things were difficult for me. The first issue was writing in a second language (English), so it took me a long time to write down my ideas. The other difficulty was deciding what to include and what not to include, especially when it came to the people involved. My friends, and even my uncle, are in the book. We handled it the best we could, especially so we wouldn’t cause people harm in the future. These were difficult decisions to make.

[Read: The complexities of life amid conflict in Mosul]

Cengiz: And what about this process was difficult for you, Molly?

Molly: I feel like this was, in so many ways, one of the hardest things I’ve been a part of. I spent a lot of time on the phone with Marwan, while he was in ISIS-controlled internet cafés. It’s very fucking hard to communicate online with one of your best friends for months, while you think they’ll die in a bombing or fucking get caught and killed by ISIS.

Once, ISIS cut off all the private internet connections, and closed all the internet cafés. Marwan messaged me and said, “I have 15 more minutes to talk to you. If I can’t get online again, this is such a wonderful thing, I’m so happy we met.” I didn’t speak to him for about a week. Eventually, he was able to get into some internet cafe and we were able to connect again.

Cengiz: Marwan, how did you feel about the risk you took to get the images for the book?

Marwan: At that time, I had no plan for the future because it’s impossible to have a plan when you’re living in a situation like that. When this opportunity to do something special came up, I did not hesitate even though there was a risk every day. At the time, I was working in a café where probably 90 percent of the customers were ISIS guys. Every day, I would face the potential of getting arrested, but I realized the rare access that I had. I knew that no western journalist, no foreigner, could come and do anything like I was doing.

Cengiz: Do you plan to translate the book or distribute it in Syria?

Marwan: I’m not sure we will ever be able to distribute it in Syria, but I definitely want it to be translated into Arabic. There’s a chance that it will be banned in many countries, and that very few publishing houses in the Arab world will publish it. But it’s very important for me that it gets translated into Arabic. We also want to find a Turkish publisher. We think it’s important for Turks to read it because there are many misconceptions in Turkey about Syria.

Molly: I really hope it can get translated into Arabic. There’s nothing else in my life that I’ve been a part of that’s given me more pride. It was very hard, but I’m proud, especially because Marwan is fucking brilliant. He’s a brilliant human. I feel like the structures of journalism and publishing are meant to keep brilliant working class humans, who are from warzones, from ever having any access to speak directly to anyone in the west.

Cengiz: Molly, were there any artists you used as inspiration for your illustrations?

Molly: I looked a lot at Spanish artist Francisco Goya’s “Disasters of War.” I did 82 illustrations in our book in tribute to Goya because that is the number of etchings he created for the series. I looked at stylistic things that he did, like how he would make the white go into the dark. Technical stuff like that.

I feel like Goya’s images get to a deeper truth about war by looking through surreal lens in a way that photojournalism cannot. They’re not one-to-one things, it’s not a copy of reality.

Cengiz: What does life look like now in Raqqa?

Marwan: The city is in ruins, but people are finding ways to get on with their lives. It’s not the first time they have experienced harsh conditions. Everyone’s main priority is getting water, food, and electricity. Some are thinking about education. How can we find a school? How can we teach our children so they won’t grow up illiterate?

There’s a small effort to rebuild the city. If you provide an environment where people can return and rebuild their houses without the fear of bombs or getting arrested, people will not hesitate to return home. The major concern for everyone there is the uncertainty of not knowing who’s going to control the city next.

This interview has been edited and condensed.