Some say Gundelia was part of Jesus’ crown of thorns. Now Israelis and Palestinians are fighting over the plant in the West Bank.

In the dead of night in March, three cargo trucks pulled up to a military checkpoint in the West Bank. Israeli border police brought them to a halt and pulled back a tarp to reveal hundreds of plastic bags packed with the prickly green limbs of dismembered plants, their alien flower buds peeking out.

The five Palestinian men transporting the goods were arrested and their merchandise—11 tons of greenery—confiscated in what Israeli police said was one their largest ever seizures of Akoub, a plant protected under Israeli law and celebrated at Palestinian dinner tables.

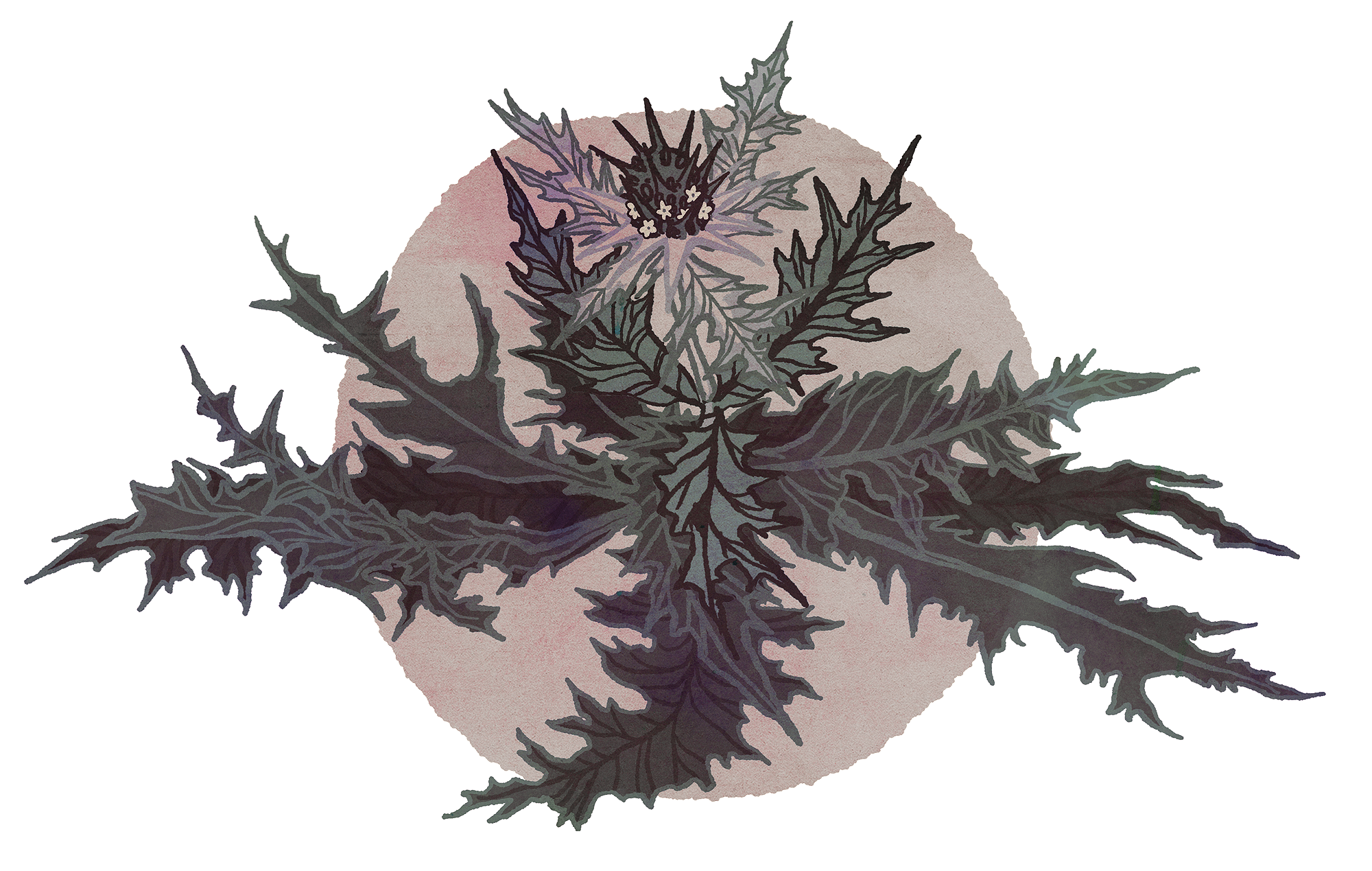

Palestinians have foraged and eaten Akoub, known in English as Gundelia, for generations. Some say the precious plant tastes like a cross between asparagus and artichoke. Others praise its subtle sweetness or tout its supposed ability to treat everything from diabetes to bronchitis. Some researchers believe its thorns may have been woven together to make Jesus’ thorny crown. Once picked and removed of thorns, those slender, sturdy stems and flower buds are traditionally thrown into stews, a soup thickened with dried goat-milk yogurt, or fried with eggs.

For many Palestinians in the Israeli-occupied West Bank, harvesting Akoub is a defining part of the hyper-seasonal culinary calendar. In late winter and early spring, around the time that green almonds and white cucumbers hit the markets, Palestinians flock to the hills to pick the coveted thistle, which still grows only in the wild. For the entirety of its brief, weeks-long season, Akoub is the hottest product in the market.

[Related: How a new Ramallah is quickly emerging from its dusty past]

Nidal al-Q’ua is an officer in the Palestinian intelligence services, but his real passion is agronomy. On spring mornings he will trudge through the hills near his West Bank hometown of Beit Lid, 35 miles northeast of Jerusalem, to hunt the plant that he says he can sell for upwards of $20 per kilo. Nidal, 46, grew up eating Akoub, scouring the hills looking for it alongside his mother each spring. His wife, Rana, 32, became a fanatic, too, after marrying him ten years ago. When Akoub comes into season, the pair explains, their area becomes a frenzy of picking, buying, and selling. Families purchase extra to freeze and cook later during the Muslim holy month of Ramadan–assuming their stock lasts that long.

But picking Akoub has become a problem in recent years. Israeli authorities say commercial pickers have severely depleted the wild thistle’s population. Over a decade ago, Israel’s Nature and Parks Authority placed Akoub on its protected species list, threatening pickers with thousands of dollars of fines and possible arrest. It’s only in the past year that Israel has started to enforce this ban in the West Bank, the territory Palestinians want as a part of their future state.

In pursuit of Akoub, hungry—and, in some cases, profit-driven—Palestinians are now pitted against the Israeli military, tasked with enforcing environmental regulations in the West Bank. Now pressures from both sides threaten to diminish the plant’s abundance in the wild or its survival within the local culture.

[Related: Welcome to the food capital of the West Bank]

It takes Nidal 20 minutes—the dense shrubbery of wildflowers, grasses, and edible seed pods crunching underfoot—to spot it: a young Akoub, with its purple spine surrounded by broad thorny leaves, like a small fern, only a little more threatening. He pulls the plant up by its roots with a smile. “It is not endangered like they make it to out be,” he says.

Ask Nidal and Rana what makes this plant worth hours of foraging and cleaning thorns and they’ll have a hard time telling you. They look at each other and chuckle, unsure where to begin. “There’s a sweetness to it,” Rana says.

“It’s just not like other plants,” adds Nidal.

Gundelia is a finicky perennial plant. The roots become dormant in the summer and resprout in the autumn. To propagate, its flowers must fully blossom into a purple and yellow orb and then dry out. This bushy top then detaches from the base and becomes a kind of tumbleweed, tossing its hundreds of dried seed pods around the arid summer landscape. If Gundelia is picked before completing this process, it cannot spread.

The barbed flower is abundant throughout the region—it grows in Lebanon, Cyprus, Turkey, and Iran among other countries—but Israeli ecologists have long watched Palestinians pick Gundelia in dismay. Unfortunately for Gundelia, its most-delicious state is before the young flower buds bloom, when the stem is green and tender, long before the seeds can spread. Ori Fragman-Sapir, a professor at Hebrew University and editor of Flora of Israel Online, says he has seen massive carpet blooms diminished and in parts of the southern West Bank, the plant has disappeared altogether.

“If it were collected only privately for someone’s family that’s ok, but this plant was collected commercially,” Fragman-Sapir says. “Although it’s not a rare plant, it is under threat of overcollection.”

While nature preservation is never easy, in the West Bank, the task of preserving a tumbleweed that traverses Palestinian towns, Israeli settlements, and the no-man’s-land in between is mired in decades of distrust and enmity—and hits at the root of the Palestinian quest for statehood.

Israel captured the rugged territory in the 1967 Arab-Israeli War and now manages everything from courts to water through military control, a state of affairs viewed by most of the international community as an occupation. Civilian matters, like ecological conservation, are carried out by a defense body dubbed the “Civil Administration” and enforced on Palestinians through military orders. The West Bank’s 51 nature reserves are subcontracted to Israel’s Nature and Parks Authority, which operates under the umbrella of the military.

In 1994, Palestinians were given partial autonomy in parts of the West Bank with the establishment of the Palestinian Authority (PA) government. The land was divided into three categories, known as A, B, and C, scattered across the 2,260-square-mile territory. In Area A, which includes all major Palestinian cities, the PA has full control and is free to administer environmental policy as they see fit. Area B is under partial Palestinian control, and Area C—roughly 60 percent of the West Bank—is under full Israeli control. Nearly three million Palestinians live in the entire West Bank, according to Palestinian figures, and around 400,000 Jewish settlers, mostly concentrated in Area C, where every rock and tree is fought over.

The confusing patchwork of Israeli and Palestinian jurisdiction is marked by military checkpoints and blaring red signs that forbid Israelis from entering Area A. To avoid traffic tickets, Palestinian taxi drivers always buckle up when crossing into Area C, where Israeli police patrol.

Akoub, being a tumbleweed, doesn’t adhere to these political lines, and grows in all three areas. Still, it tends to favor the undeveloped, hilly terrain that lies mostly in Area C, resulting in a fierce cat-and-mouse game between Israeli environmental inspectors and Palestinian commercial pickers.

One picker told a Palestinian news website this year that he was “hunted” by an army helicopter and environmental authorities while picking in the northern West Bank mountains. In another case in 2014, Akoub picking turned deadly as Israeli soldiers shot and killed a 14-year-old Palestinian boy who attempted to cross the fence separating the West Bank from Israel to forage on the other side.

Still, an ecologist with the Israeli defense body that administers the West Bank complained that eight inspectors for the vast territory are not nearly enough to control the mass waves of Akoub picking. “Our efforts are only a drop in the ocean,” he says.

Instead, Israeli-manned checkpoints separating the Israeli-administered hills from the Palestinian cities have become the primary enforcement mechanism. Some pickers have been caught with hundreds of thousands of dollars worth of Akoub.

Chef Fadi Kattan, who runs the Hosh al-Syrian guesthouse and Fawda Cafe in Bethlehem, fondly remembers how his mother cooked Akoub: fried, with lemon juice and tahini. At his restaurant he likes to play with the traditions, serving the illegal stems and flower buds with parsley oil and pomegranate seeds or dipped in chocolate and sprinkled with pistachio.“I don’t understand how an occupying force can allow itself to forbid culinary tradition that is not at all linked with its own culture,” he says.

While “trendy” chefs around the world are promoting foraging, he adds “in this place you have an occupying force that’s saying it’s forbidden.” Though many Palestinians agree on the need to protect Akoub, they also see Israeli conservation efforts as inherently illegitimate, just another part of a system that prevents them from using large swaths of land for agriculture.

Foraging, which requires Palestinians to traverse geo-political boundaries, is uniquely subject to the combination of Israeli movement restrictions and environmental damage caused by over picking. Saying they’ve been over-picked, Israeli authorities have already outlawed foraging for herbs like wild sage and Zaatar, the tangy oregano-like herb that forms the foundation of so much of Palestinian cooking. But domestication, Kattan argues, in addition to uprooting a rich culinary culture built on seasonality, could permanently change Akoub’s lightly sweet, innately wild taste. “Zaatar was changed totally,” he says, “It lost that spicy little kick.”

If Israel were serious about conservation, Kattan says, it would leave Palestinians to pick and grow Akoub the way they have for generations and focus instead on stopping the expansion of Jewish settlements. “The largest environmental threat is called the settlements. Har Homa, which is opposite to us, used to be a forest,” Kattan says. “Now it’s a forest of white buildings.”

Husam Taleeb, who heads the PA’s Department of Forests, Rangeland, and Wildlife, eats his Akoub with chunks of lamb stewed with yogurt. He acknowledges that the plant deserves preservation efforts, but not in a scheme created and enforced by Israel. “I think if we want to protect the plant, we can protect it inside some areas,” he says, “but not in all of Palestine.” Taleeb says he is open to protecting Akoub in the areas that are defined as nature reserves by Palestinians, not Israelis.

Nature reserves, which constitute around 12 percent of the West Bank, are despised by most Palestinians. They see these reserves as yet another Israeli restriction—along with closed military zones and settlements—that have reshaped the landscape of Area C. In some instances, those nature reserves have been adjusted to make room for expanding Jewish settlements, which does nothing to quell deep-seated Palestinian suspicions of Israel’s conservation efforts.

Shepherds are a common sight alongside the highways, and many Palestinians still make their living through small-scale farming, often battling over land with Israeli settlers. But in a 2016 report, the United Nations said that decades of Israeli control had created a “structural deformation” of the Palestinian economy, a result of the “continuous process of de-agriculturalization” caused by Israeli restrictions. A blanket ban on foraging Akoub, says Taleeb, “is really just a reason to prevent Palestinian farmers from using Area C. For us, it’s political.”

Fortunately, the rolling hills outside Beit Lid where Rana and Nidal al-Q’ua hope to start their Akoub business are in Area B. Rana, the Palestinian intelligence officer’s wife, has already begun to till a small patch of land where she hopes to tame the wild plant in the West Bank’s rocky reddish dirt.

Ori Fragman-Sapir, the Israeli ecologist, says it is time for Palestinians to adapt to a changing environmental reality. He thinks farming Akoub is the best way forward. “It made sense for Arabs to pick it when Israel was not that populated,” he says, referring to both Israel and the West Bank. “Today we are confronting the situation where Israel is like a small Hong Kong—where nature remains in small islands in between.”

Rana and Nidal are among the first Palestinians to try capitalizing on that new reality, cultivating Akoub to take advantage of the economic window created by its natural scarcity and increasingly rigid Israeli restrictions. Taleeb says he knows of around ten farmers who have been trying their hand at germinating the plant over the last two years. “There’s a lack of Akoub in the Palestinian market, and I wanted to grow something that will fill this gap and make income for my family,” says Rana, as her son nibbles on a stem of wild fennel.

Soft-spoken but visibly passionate, the mother of three is the driving force behind the business plan. For two months, she collected prickly brown seeds for her first crop every time she ventured out into the hillsides with her family. No one in her town knew anything about how to plant the seeds, so she went online and, through a series of careful internet searches, taught herself how to cultivate the plant. During a recent visit, Rana showed off with pride the rewards of her years of hard work: a black plastic bag full of hundreds of seedpods and dozens of saplings.

“If it all works out, Akoub will go from being a wild plant to something like any other vegetable,” she says.

Rana planted a test batch of Akoub in 2015 and harvested it for the first time in 2017. Her second batch of 1,000 kilos (about 2,200 lbs) sold out in one week. Now everyone in Beit Lid knows she has the goods. Soon, she hopes to expand the crop to a five-acre plot and become the central source for Akoub seeds in the West Bank, assuming the right investors turn up.

“This is all empty,” Nidal says pointing out over the fields. “We want this to be filled with Akoub.”