[Looks at Photo] I’ll Have What They’re Having

[Looks at Photo] I’ll Have What They’re Having

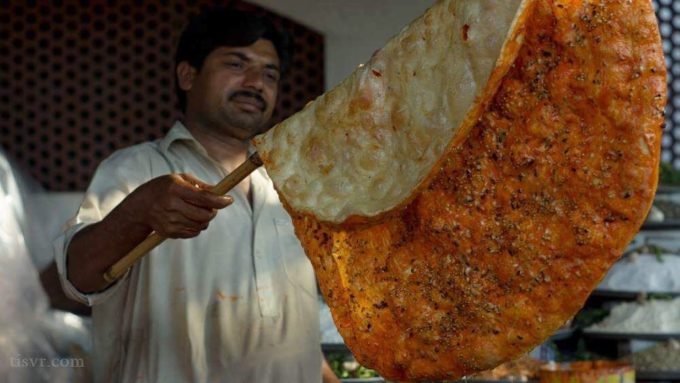

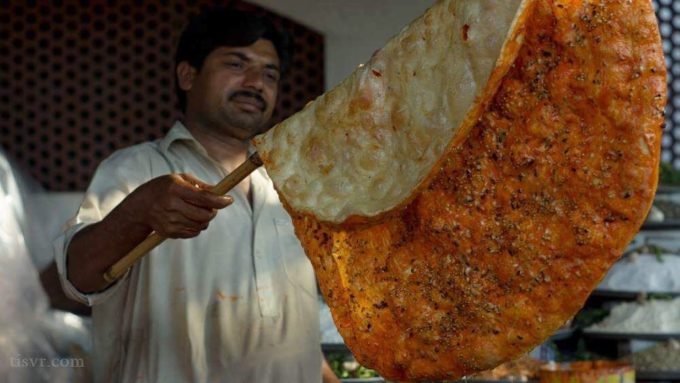

Katlama in Lahore

One of my earliest memories is of eating gigantic, deep-fried flatbreads smothered in spices at my grandparents’ home in Lahore. The bread was delicious, and according to my mother, after we had come back from our trip I ordered my father to search the city for a katlama like the one we had in Lahore.

I had forgotten about that, until I visited Lahore again many years later. I had only come for a day, and the original plan was to set off for home early next morning, but the smog deterred us. We were in the car debating where to get breakfast as we waited for the haze to clear. The long fingers of dawn had crept up across the horizon, and the municipal workers were sweeping the street. It was strange to see a city, usually bustling with people, clogged with traffic, so empty, quiet, and vulnerable.

We drove to old Anarkali Bazaar in central Lahore, named after the legendary figure, Anarkali, a courtesan that the Mughal Emperor, Akbar, supposedly ordered to be buried alive. The bazaar was shrouded in fog, but we caught glimpses of the British and Mughal architecture. A few nameless roadside stalls were open, and there was a small queue of people in front of them. We watched as one of the vendors lit a fire under a huge, blackened wok full of oil. Another person behind him deftly rolled dough into sizable balls.

I asked him for breakfast recommendations. He parroted a list of options: halwa puri, channa cholay, katlama, qeemay ki tiki (sometimes known as qeemay ka katlama), etc. We ordered the katlama and qeemay ki tiki. The vendor produced a large rolling pin and worked on the dough, stretching it. He threw a blend of chili powder, pomegranate seeds, and crushed cumin in a thick mixture of besan (chickpea flour) and spread it all over the dough. He then carefully tipped it in the sputtering oil until it was completely submerged.

The vendor, between flipping the katlama and drinking his second cup of chai, told us that the bazaar was at least a century old—perhaps even older than that. They opened shop at six every morning, except on special occasions such as an urs or mela (the festival to mark the death anniversary of saints), where they opened even earlier to accommodate devotees. The prepared food was usually all gone within two hours.

There was no place to sit, and like other bystanders having their breakfast in front of the stall, we tore off pieces of hot katlama right there. There was a delightful crunch of the pomegranate seeds, and the bread was flavorful and crispy around the edges. We started on the qeemay ki tiki: a deep-fried, flaky pastry pie filled with spicy minced meat. There was grease on our fingertips and on the sides of our mouths; pastry flakes scattered across the folds of my dupatta; meat and pastry and bread in our bellies. And my favorite part: it was even better than how I remembered.