Thanks to a paranoid Communist past, the tiny nation is littered with fortifications against an attack that never came.

Albania has a bunker problem. Across this tiny country of 2.8 million people, thousands of bunkers continue to dot the landscape. How many thousands, no one knows. Indeed, no one knows how many were built in the first place; estimates range from 150,000 to 750,000. Accurate records are either lost, destroyed, or weren’t kept in the first place.

Some bunkers are little steel pillboxes, with just enough room for a man and a machine gun. Others are enormous underground complexes, the size of villages, designed to protect the entire Albanian government from the nuclear attack they thought was imminent.

They run from the coast to the mountains, north from the former Yugoslavia, south to Greece. They never saw action, and are today considered a monumental waste of money and resources. Communist Albania didn’t have enough for bread or decent housing, but apparently had plenty to build one bunker for every 11 Albanians.

But they are not without their uses, and 35 years after the last bunker was built, Albanians are coming up with all sorts of ingenious ways to turn concrete lemons into lucrative lemonade.

To understand why Albania invested so much of what they had into bunkers requires a crash course in post-war Albanian history. Following the defeat of Albania’s Fascist and Nazi invaders, Enver Hoxha’s communist Albanian Party of Labour took power.

They ruled with an iron fist. More Stalinist than Stalin, Hoxha’s rigid ideological vision caused him to break, one by one, with every other Communist nation in the world—Yugoslavia, the Soviet Union, China—until, by the end of the seventies, they were without allies, alone against the world.

The borders were sealed, the secret police were everywhere, and the citizens were reminded daily, if not hourly, to be ready to defend the world’s last pure Communist state.

The bunkers were a key part of this program of self-reliance in the face of constant threat. According to the founders of Bunk’Art 1 (more on them later), bunkerization was first thought of in 1964, following a state visit to North Korea, and in 1971, the government decided to implement the program. The first bunkers went up in 1975, the last ones in 1983.

Fatos Ajazi was an army mechanic in the 1970s, and helped build the first bunkers, including the ones that now dot his farm in Ndroq, four miles from the coast. “We have the best bunkers in the region,” he boasts.

They’re certainly impressive. His whole farm is a former army garrison, and he keeps his sheep and chickens in the ruined concrete buildings, some of which he’s restored. Hike about five minutes up behind the property, through the woods, and there is a line of large, mushroom shaped bunkers, about eight feet high, facing the sea.

They’re part of a long column of defenses between the sea and Tirana, the country’s capital. Inscriptions on the inside wall reveal they were built in February of 1981. The floor is covered in sheep shit; the major use for these bunkers now is sheltering animals.

But in 1995, they had a wedding on the property, and the bunker was used as a kitchen. And in 1999, during the Kosovo War, 1800 Kosovar refugees sheltered on the farm, many of them sleeping in the bunkers themselves.

It was a doctor assisting the refugees who gave Ajazi the idea of turning the area into a private hospital: the sea air, he says, makes it ideal for convalescing patients. Ajazi’s other idea is to turn it into a resort, with a pool, hotel, restaurant, and animals. The area is steeped in history, from early Ilyrian settlements, to the Romans, to the spot where the first partisans attacked Italian invaders in the Second World War, to the bunkers. Ajazi hopes people will open their wallets to be a part of that.

Throughout the country, people are turning bunkers into businesses. Like almost all other post-Communist states (and some current Communist ones), Albanians have taken quite a shine to capitalism.

On the beach at Durres, in the place where Pompey defeated Caesar in 48 BC, Lalaia restaurant serves up bowls of steaming mussels and plates of deep-fried red snapper. Though it is round, you’d never know it was a bunker until you see the storeroom. A waiter has to pry open a foot-thick concrete wall to enter. Within, it looks like a prison cell, dark and dank, except that it’s full of wine.

We would play on the bunkers… Unless someone used them as toilets

Further up the beach, in the upscale area of Qerret, one bunker houses a pizzeria, the other a bar, though they’re both closed for the season. Many others work as the foundations for bridges and piers.

“It used to be full of them here,” says Elton Çaushi, a tour guide with Albania Trips, who often takes visitors to the bunkers. “They thought an attack would come by sea, like in World War II. But now they’re mostly gone or covered up.”

As a child in the eighties, Çaushi used to come to the beach and stay in what he describes as a “barracks.” But he thought it was heaven. “It was wonderful,” he says. “We would play on the bunkers, around the bunkers. Unless someone used them as toilets.”

They’d also function as makeshift love motels. “In the seventies and eighties, everyone used to lose their virginity in these things,” Çaushi says. “There were no hotels or motels, and the society was too [strict] to bring your girlfriend or boyfriend home.”

Today, bunker businesses pay a sort of “rent” to the local government–Çaushi says it can be anywhere between $200 and $500–but it’s unlikely the Ministry of Defense, who technically own the bunkers, see any money.

A few years ago, the government gave concessions to come and demolish the bunkers and sell them for scrap, Çaushi says. But it was a corrupt process, and all the money went into officials’ pockets.

In Marikaj Village, 10 miles west of Tirana, farmer Hajdark Kuçi reclaimed his family’s land from the Albanian government following decommunization in the nineties, a terribly chaotic time that is remembered even less fondly than the Communist era.

During the Albanian Civil War of 1997 (a disputed term, as many Albanians say it wasn’t so much a civil war as a period of mass unrest and rampant gangsterism) one of the bunkers was full of leftover dynamite. Kuçi had to hire men with Kalashnikovs to protect it. And not just from thieves: throughout the country, there were stories of people flicking cigarettes into dynamite-filled bunkers, with the expected results.

Sixteen bunkers are on the property, most of them tunnels in the mountain. He uses them to store equipment, including a still for making raki, the home distilled spirit almost every Albanian–Muslim or otherwise–distils and drinks.

But he’s hoping to turn one of the bunkers into a restaurant. Like Ajazi, he’s hoping to run a resort, especially given the wildlife that lives on the property and in its artificial lake. He’s fixed the walls with brick and the ceiling with wood rafters. “The main problem with the bunkers is insulation,” Kuçi says. “They don’t have enough, so they leak.”

The other problem is the government doesn’t want him to touch them. They are, after all, government property. “If you do nothing to do them, [the government] does nothing,” Kuçi says. “But you do something, and they start to cause problems and get involved.” But since they’re on his land, he figures there’s not much the government will do about it.

“They come to remind us not to tamper with them,” Kuçi says. “So I tell them to take them away.”

Not all the bunkers have been remade with the explicit goal of making money. Bunk’Art is a non-profit project that aims to convert bunkers into museums and art spaces. They have so far converted two of Albania’s most enormous bunkers: Bunk’Art 1 is several miles outside of Tirana, and is built into an underground bunker meant for use by Hoxha and his government in the event of attack. Bunk’Art 2 is a smaller bunker in the center of the city, once linked directly to the Ministry of Internal Affairs.

Inside Bunk’Art 1, they say the structure was completed and inaugurated in 1978 after six years of construction.

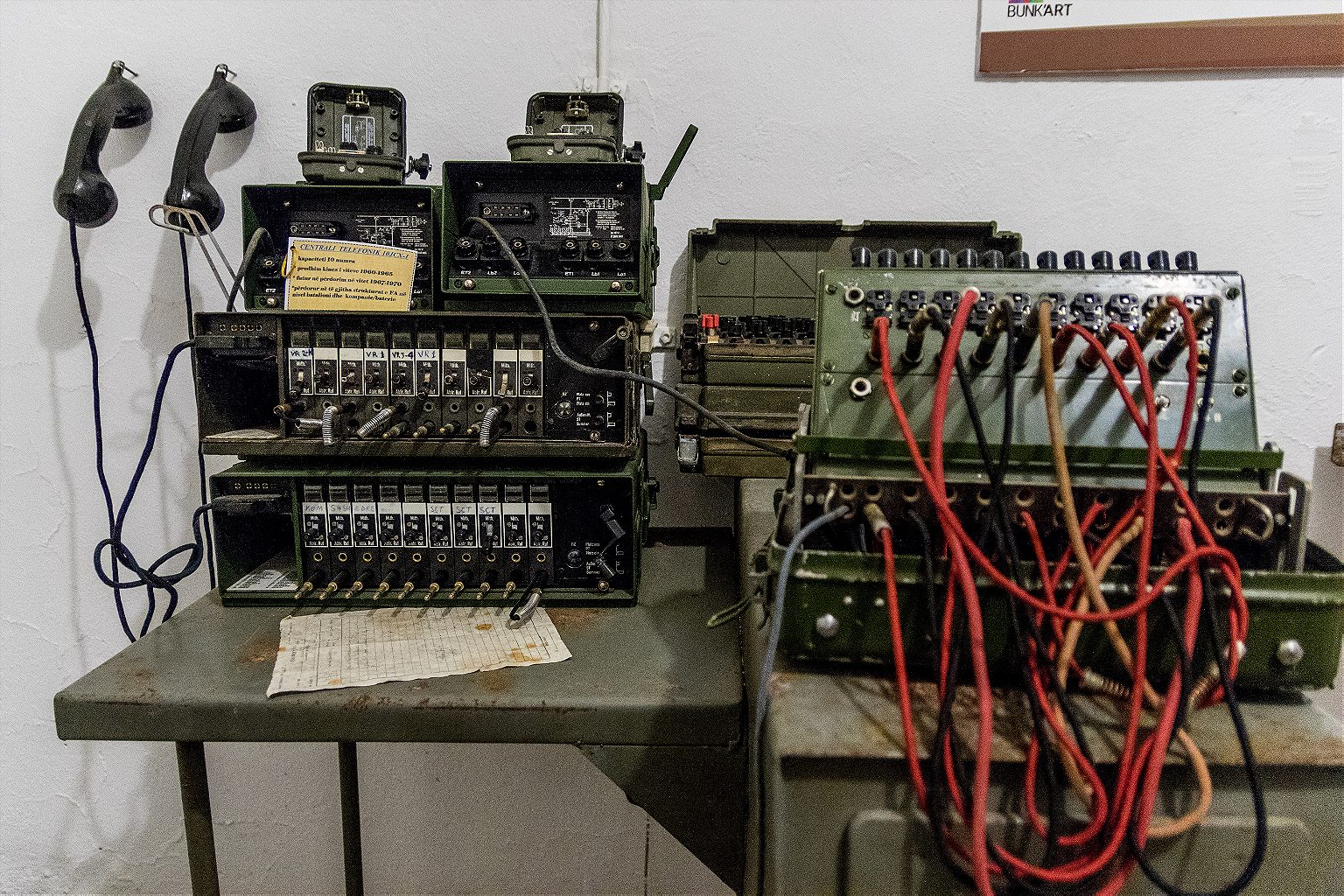

There are offices with phones and typewriters, televisions and radios, where the government would have conducted the day-to-day operations of running a country under nuclear attack. There is a whole apartment for Hoxha himself. In one room, there is a Commodore PET personal computer from 1977. How they got that into the country, at the height of Albanian isolation, I can only imagine. There is also an enormous hall where the government could have convened.

Other rooms are set up to explain the history of the Albanian armed forces, from the Italian invasion of 1939 to the fall of Communism in 1990. There are art installations as well, including one that features a bronze bust of Hoxha held in a basketball net.

But it’s Bunk’Art 2, though smaller and less historically important, which is the more horrifying. Built between 1981 and 1986, it’s also entirely underground and built to withstand a chemical or nuclear attack. The entrances and exits are new, since before you could only access it by underground passage from within the Ministry of Interior’s building.

Most of the museum is dedicated to the Sigurimi, the much feared Albanian secret police. Like the KGB in Russia or the Stasi in East Germany, this was not an organization with great moral qualms. One room lists the tortures inflicted on prisoners. There are riot police uniforms, including an original protective suit worn to train attack dogs; huge chunks of it are ripped out. Spy equipment, like hidden listening devices, looks straight out of a Cold War spy film.

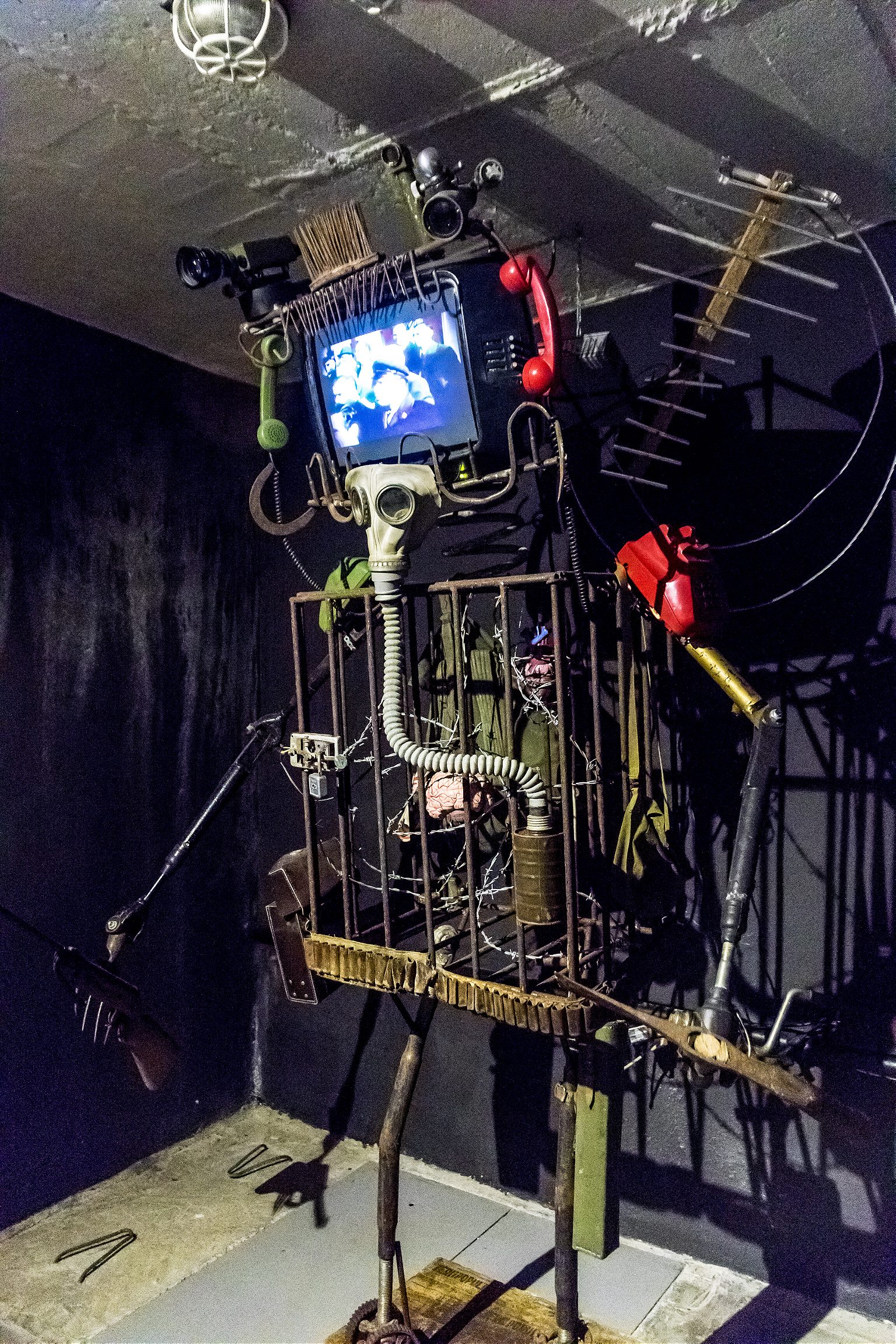

The most fascinating part is a sculpture called “The Monster of the Dictatorship,” by Rajmonda Zajmi Avignon. It’s an anthropomorphic piece, with a TV as a head, a gas mask face, two phones for ears, video cameras on top for eyes, a cage for a torso, and in the cage a brain wrapped in barbed wire. In its hands are a gun and a pickaxe, which refers to the slogan of the Albanian Communist Party, “We build socialism by holding the pickaxe in one hand and the rifle in the other.”

Though no one has counted how many bunkers still exist, what is clear is there are many fewer now than before.

At the Memorial to Communism, a park in downtown Tirana, there are several original pillbox bunkers, covered in spray-paint and bird shit, facing the Prime Minister’s office. Though many Albanians would like to see them dug up, others want them to stay, and not just for the tourist dollars.

Ajazi, the farmer who’s thinking of putting a hospital on his bunkered property, thinks it’s terrible they’re being removed.

“It’s bad to destroy the bunkers. They’re a part of our history. We shouldn’t forget,” Ajazi says. Some people have approached him to buy the bunkers and demolish them for the steel. But even if Ajazi did own them, which he doesn’t, he would never sell them.

“It’s sad to see them go away,” he sighs.