A visit to starkly different neighborhoods in Istanbul reveals a city divided in the run-up to a historic vote.

On April 16, voters in Turkey will say yes or no to a new constitution that could change the country’s parliamentary system to an executive presidency in a referendum that has been fiercely contested on both sides, sparking domestic turmoil and international incidents. Yes voters, or proponents of the presidential system, which is closely associated with President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan and his increasingly authoritarian government, argue that the new system would be similar to the American and French model of government, while opponents say it will compromise the separation of powers and the independence of the judiciary. With a Yes vote, President Erdogan could rule Turkey until 2029. Polls show both sides are neck and neck.

A visit to four neighborhoods in Istanbul—liberal-secularist Beşiktaş; conservative Üsküdar; leftist Kadıköy; and Eyüp, a place steeped in Islamic history—reveal a city deeply divided in the days leading up to the historic vote.

Beşiktaş—The European Side of the Bosphorus

In Democracy Square, a woman in a headscarf dances while waving the Turkish flag. She’s wearing a shirt that says Evet (Yes) and she’s moving in front of the folks whose shirts read Hayır (No). The Hayır truck blares Baskanliga Hayır! (No to the President!) to the tune of Queen’s We Will Rock You. The Yes side blasts the 2014 campaign song that became a runaway hit after last summer’s failed coup attempt, Re-cep-Tay-yip-Er-do-gan! Above, a screen replays dramatic moments from that evening: of tanks on the streets, of unarmed civilians facing down soldiers. I score a Turkish coffee cup from the Evet tent.

Both sides pass out flyers and pamphlets and make speeches for commuters waiting at busy crosswalks. A fight breaks out: an Evet campaigner claims, “This is a party election! This is a party election!” A woman from the Hayır campaign loudly protests, “This is not a party election! This is not a party election!”

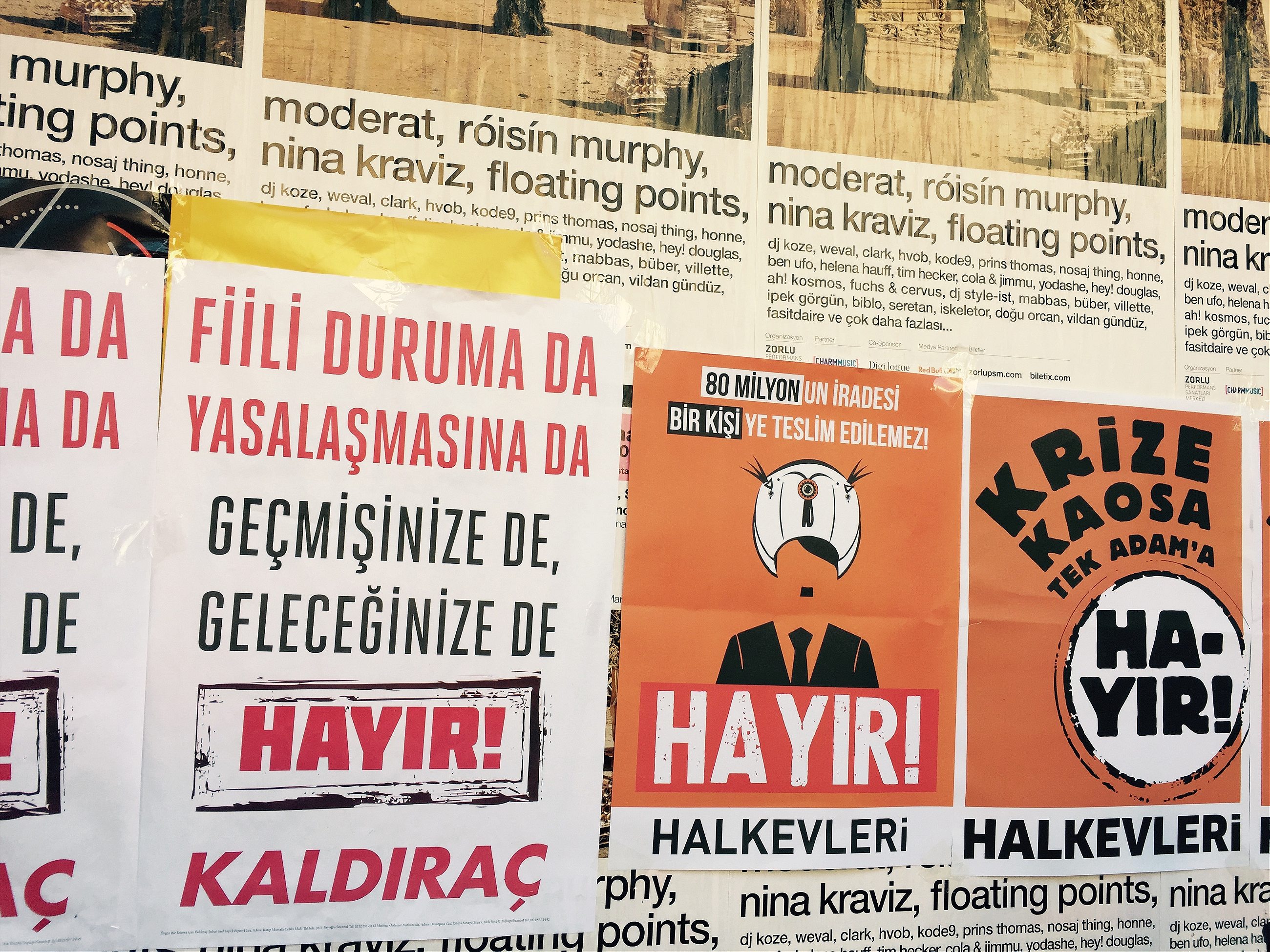

In its campaign ads, the Yes side tends to emphasize the current leadership and the ruling party, the AKP (the Justice and Development Party), while the No campaign has generally avoided mention of a specific party or politician. Traveling around Istanbul, however, it’s hard to escape building-sized portraits of the president and the prime minister. The slogan on a lot of these signs read, For a Stronger Turkey, Yes. The No side’s posters feature an innocuous young girl in pigtails smiling. Her message: For My Future, No. It’s as if the choice was between the particular of the present and the generality of the future.

I cross the street from Democracy Square and make my way to the heart of Beşiktaş. I notice a white tent with a sign that reads: If You’re Undecided Ask a Lawyer. I listen in. It appears to be a sort of confessional, where people can stop by and ask their burning questions about the constitutional changes. One of the lawyers is trying to explain the proposed system to a group of ladies. The lawyer explains, “When you look at the European examples, this is very different.” A woman interrupts, “I don’t care about Europe. What is the use of this constitution?”

Avrupa, Europe, hangs like a dark cloud over the referendum. The Venice Commission, which advises the Council of Europe (of which Turkey is a member), recently stated that the new constitution would put Turkey “on the road to an autocracy.” Then last month, a diplomatic spat between Turkey and the Netherlands erupted after Dutch authorities barred Turkish ministers from reaching the Turkish consulate in Rotterdam, a city with a large Turkish diaspora. Holland claims that Turkey was warned against holding referendum rallies on the eve of the Dutch elections, citing public order and security concerns. At the consulate, protests against the Dutch government’s actions turned violent, amid heavy police presence, water cannons, and dogs. Turkish papers flashed the headline Europe’s Dog! accompanied by a photo of a police dog attacking a Turkish protester lying on the ground.

“Most people don’t know why they’re saying yes or no,” says Poyraz, a 31-year-old fishmonger in Beşiktaş. “I myself don’t know. But I do know that I love this man [Erdogan]. If Yes wins, Turkey will become stronger.”

I wonder then, why would some say No? “They’re scared of Islam,” says Poyraz, “but this is a Muslim country. There’s freedom. See how people are living here.” He looks me in the eye: “You can be covered or not. But some say, why do you want women to be covered? And I say I’m a Muslim, I have to live this way.” (Full disclosure: I don’t cover my hair.) “Follow your own country,” he adds, “don’t follow other countries like America or Holland.”

I hop over to Mephisto, a bookstore that carries alternative zines and journals. Titles on feminism, socialism, LGBT issues, and other progressive topics line the walls. I talk to Gamze, 22, a student at Sakarya University, about why she’s voting No. Her main reason is “the quality of life for women.” She says, “No woman wants to live in this way. We’re not able to walk the streets safely. I’m a student and when I graduate there are no jobs. There’s an unemployment crisis, especially among young people.”

Beşiktaş has the feel of a college town. There are several universities nearby. Young people in various types of dress do what young people do everywhere: they make out. They try to look cool while smoking. They wear nose rings and Che T-shirts. On game days, the bars of Beşiktaş are filled with football fans cheering the local team, also called Beşiktaş. It’s a typical evening at a pub; the television on loud, the announcer giving the play by play, the sudden roar after a goal is scored, the clink of toasts.

I strike up a conversation with Kamil, a 28-year-old computer engineer. I ask him what he thinks about the referendum. He says he’s undecided, but that he will make a decision soon. “The current system is not working. It needs to change, but I don’t know how,” he says. It’s a sentiment echoed by many, as the current constitution is a holdover from the 1980 military coup. Back then, the ruling military junta helped draft the constitution and then put it to a referendum. It passed with 92 percent of the vote.

Kamil doesn’t really have a party and says his vote changes with every election. Now, he’s closely following each side’s promises. I ask him about what a lot of No voters and opponents of Erdogan are scared of, that bars like the one we’re sitting in now would have to close. “That’s hard to say. Turkey is mostly Muslim, but Shariah coming in? I don’t think there’s a chance,” he says.

And did Turkey’s diplomatic incident with the Netherlands influence him in any way? He says it didn’t. “I think it was more for those who will vote yes. Before every election, something like this always happens.”

Üsküdar—The Asian Side of the Bosphorus

Every day, thousands of commuters travel from the European side of Istanbul to the Asian side and back, boarding ferries from the Beşiktaş pier. Fifteen minutes across the Bosphorus, I’m in the neighborhood of Üsküdar, a more conservative place.

Various parties have set up stands to persuade people just as they hop off the ferry. A child from the MHP (The Nationalist Movement Party) booth runs up to give me a pamphlet for the Yes side. When I ask him why he’s for Yes, he says he doesn’t know and runs away. A woman passing out No literature with her young daughter reaches out to hand me a flyer, but it blows away in the wind. “It’s because God doesn’t want you to win,” mutters a lady in an abaya, walking past us.

I talk to Uğurcan about the referendum. He’s a student at Istanbul University, manning a No booth for the CHP, the secular-leaning Republican People’s Party. Across the street, the call to prayer begins from Mihrimah Sultan Mosque, its loudspeakers broadcasting the azaan towards the Bosphorus, and birds flutter away in formation. It’s a sight to behold, but Uğurcan looks visibly agitated. He wants to move to a quieter location.

He tells me his reasons for voting No: “The president can throw out the parliament. For the vice presidency, he can pick his relatives. This very system was realized in Azerbaijan this year. The president there selected his wife.”

Uğurcan goes on to explain how hard it has been for the No campaign. “If you look at the ads and boards everywhere, they [the Yes side] are using state facilities and resources. In Ümraniye, there was an attack against our No campaigning friends. There was also an incident in Esenler,” he says, naming various neighborhoods throughout the city. According to reports, the atmosphere for No campaigners has been somewhat difficult, as some elected officials have tarred those who support No as terrorists and traitors. For example, the mayor of Ankara, Melih Gökçek, recently tweeted a photo essentially equating the No side with ISIS leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi and Fetullah Gülen, an exiled cleric who Turkey claims masterminded the coup attempt last year.

I make my way towards Mihrimah Sultan Mosque. Tiny stools and tables sit arranged against its walls. Bystanders and the faithful, old and young, sip tulip-shaped cups of tea and play with prayer beads. There’s a honey store behind the mosque, and off to one side runs a staircase that leads to a coffee shop called Aşiyan Book and Coffee. It’s outfitted in a neo-Ottoman style—chandeliers, gold frames and velvet chairs—complete with classical Turkish music softly wafting through the space. The specialty here is the strong coffee served in small cups, chased with shot glass-sized helpings of sherbet and water. I’m tempted by the array of glazed deserts behind the glass cabinet.

I speak with Ayşe, 26, who says she’s voting Yes. “People who say No have a lot of prejudice,” she tells me “The headscarf, they’re scared of it, of people who wear it. Why?” She continues, “This is partly our fault. We haven’t explained ourselves, we’ve closed ourselves off. But why is this prejudice there? Jewish traditions, Christianity, all the religions of the world have their rules, why can’t we?”

I interrupt her, asking why some would say they don’t want a “one-man regime,” as is the refrain among No supporters. “In that case, another president can come after him. The CHP can come next,” she says. “Why do I support this president? He ended the headscarf ban. I couldn’t go to school to study to become a mathematics teacher. Now, I’m a teacher of religion. I could not become a mathematics teacher.”

Kadıköy—Across the Golden Horn

About a 20-minute drive away from Üsküdar, minus the traffic, lies Kadıköy. It was once the ancient Greek maritime town of Chalcedon, called City of the Blind because its citizens supposedly settled on the Asian side, directly across the more beautiful Byzantium and its Golden Horn. Now, Kadıköy is a neighborhood known for its cafés, bookstores, nightlife, hobby shops, and antiques. Whole blocks are devoted to bars and pubs. Synagogues and large churches of varying denominations—Greek, Armenian, Catholic—stand among the buildings here. Bold crosses jut into the sky.

Kadıköy is a strong No holdout. I ask a woman on the street about her vote, and she doesn’t hesitate. “Of course No. Everyone in Kadıköy will say No.” She refuses to discuss the matter further. Hayır! jumps out from the walls, the streets, the store fronts. Stickers and flyers from various parties, such as the HDP, the pro-Kurdish People’s Democratic Party, and the TKP, the Turkish Communist Party, show the breath of political affiliations campaigning against the presidential system. The posters are colorful in bright oranges, greens, and purples, animated like cartoons. A popular one is the outline of a man, a white turban on his head, a black smudge of a mustache above his lip, evoking a Turkish twist on a certain German politician of days past.

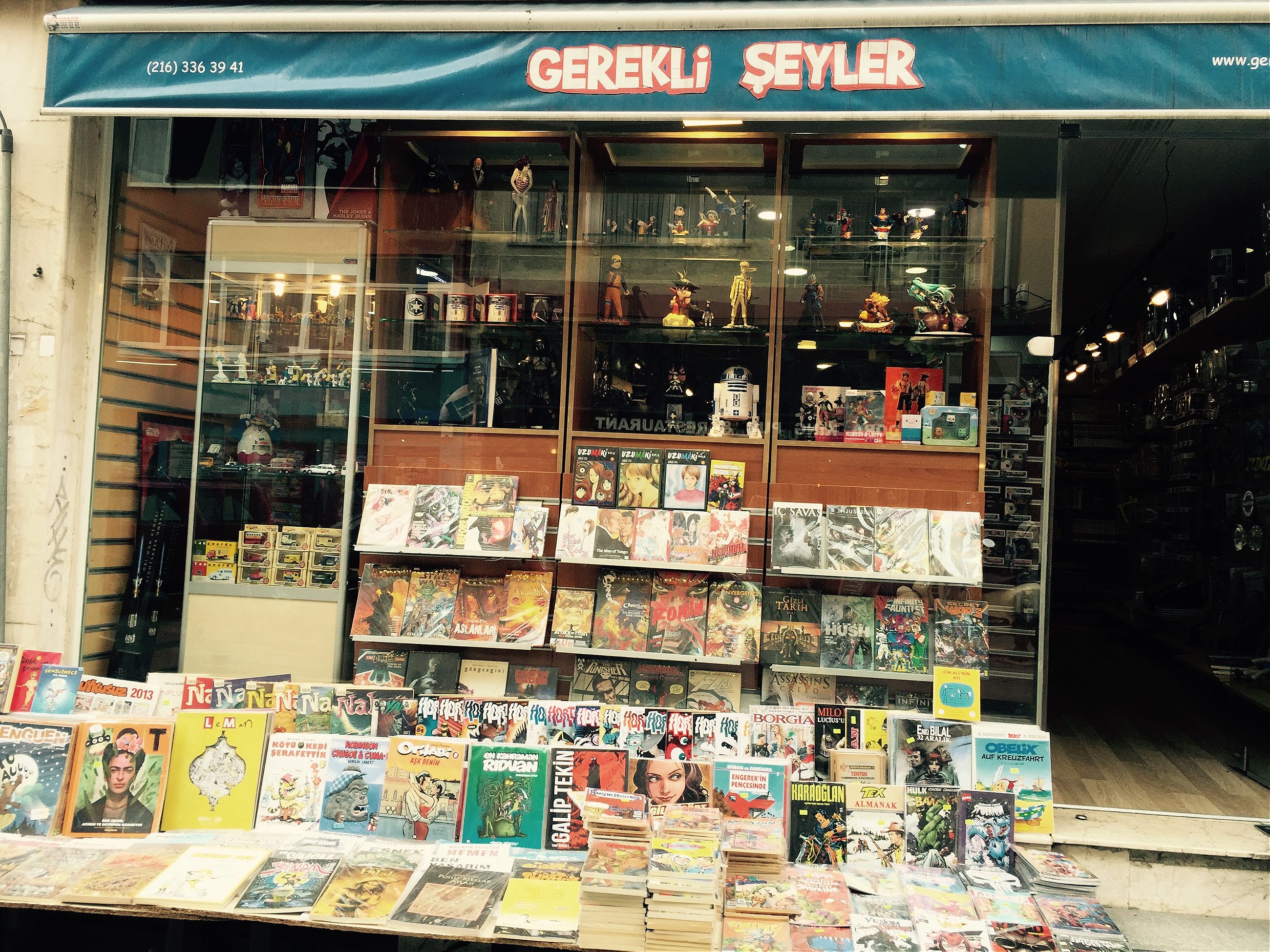

I make my way to a comic book store, Gerekli Şeyler—or Necessary Things—which offers a wide selection of Japanese manga books, American graphic novels, works by Turkish cartoonists, and action figurines. There’s a particular genre of historical graphic novel that lewdly depicts Ottoman sultans and their concubines alongside gory drawings of janissaries in their European conquests. Perhaps an alternative to the highly-produced and overly-scripted Ottoman soap operas that have invaded Turkish television in the past decade.

I talk to Arda, 32, as he thumbs through a book, about why he’s voting No. “This is the last stop. There will be no return to democracy after this,” he says. I ask him why some might say Yes to the proposed constitutional changes. He shrugs and simply laughs, “They’re not reading. They don’t read.” His friend beside him couldn’t help but chuckle at this. Arda continues: “Politics. It’s like selecting a football team. People aren’t thinking, they just follow.”

One of the things that first captivated me about Istanbul was the diversity of lifestyles here, that places like Kadıköy could exist alongside a neighborhood like Üsküdar. I was impressed by the surface-level pluralism of this city. A woman in full chador rubbing elbows with a scantily clad punk kid, someone casually sipping a beer as the call to prayer echoes. It’s beautiful and singular. It’s also delicate, even precarious.

I talk to Meltem, 24, who works at a bar. She says she’s voting No because she works at a place that serves alcohol and she really does’t like Erdogan. She laughs as though this opinion is obvious. “The government can quietly pass all sorts of restrictions under this new system,” she says. I’ve heard many dismiss the prospect of Shariah outright, but Meltem was one of the few people I met who’s serious about it. “A ban on alcohol is possible. They’ve already been laying the groundwork.”

I think about Ayşe in Üsküdar, her feelings about the prejudice she faces, and the headscarf ban that prevented her from being a mathematics teacher. I ask Meltem, do you think those who say No have some sort of prejudice against those who say Yes? She doesn’t think so: “If yes wins, they won’t share the country with the no voters. They think those who say no just don’t like the AK party [the current ruling party]. But they don’t allow other parties to emerge. The AK party knows that if the no voters stand together, they can come up with a party that can really challenge them.”

Eyüp—Outside the Old City Walls

After the fall of Constantinople, the Ottoman Turks renamed this quarter of Istanbul Eyüp, after the late Ayyub al-Ansari, who was a close companion of the Prophet Muhammed. Ayyub al-Ansari died in the first Arab siege of Constantinople, and his tomb rests inside Eyüp Sultan Mosque, a marbled complex consisting of a mausoleum and prayer halls. Muslim worshippers gather to pay their respects and take selfies with blue iznik tiles that adorn the walls. Outside, fountains anchor the marble square, while vendors selling ice cream and snacks dot the perimeter. Mothers run after children, young couples hold hands. A group of girls in chadors appear to float just above the ground.

I approach them, wanting to speak about the referendum. They’re a bit wary. I can’t tell if they’re angry, scared or happy to see me. Black fabric stretches across their mouths, chins, ears, and heads. A semicircle of face is all I have to go by. One of them is really outspoken, but she’s mulling my proposition. I assure her I won’t take a photo of her, and that I’m the only one who will listen to a recording of her voice. She’s playful and starts to speak, but then stops and says “one minute, one minute,” as if she’s preparing her words. After some back and forth, she finally gives in.

Her name’s Melike. She’s 21, studies Arabic and Islamic thought, and says Yes to the proposed constitution. She points to her outfit. “Because I wear this clothing. Because I want to live an Islamic lifestyle. That’s why I say yes. In my mother’s time, it was very hard to travel around wearing such clothing. There used to be a ban on covering in schools, in the military, but that’s all gone now.”

I try to steer the conversation towards the constitution itself, and I ask her if she’s read the proposed changes. “Of course,” she says. “Now we have a president and a prime minister. When you look at the time of the caliphate, it was only one person who ruled. So, I believe only one person should govern.”

At night, the fountains light up. The last azaan of the day sounds. The Turkish flag draped at the mosque’s entrance glows crimson. The number of municipality services here is staggering. A giant screen provides a daily schedule of adult education courses, Quran classes, and community theater performances. Several street sweepers keep the marble square spotless.

I talk to Şeyma, a 22-year-old housewife who is relaxing as the evening begins. She’s covered, but I can see her face. I ask her what she thinks about the referendum, and what her choice will be. “The number of MPs [members of parliament] is quite low,” she says. “I haven’t really managed to see them, or talk to them. But with the proposed changes, there will be more MPs. They will interact with the public more.”

She lives in a CHP-dominated area and claims the No side just doesn’t want to listen. “The prejudices and nightmares are turning in their heads. They’re not seeing reality. They’re deaf and blind.”

I think about how hard it is for any person, apart from a legal expert, to make sense of a whole constitution, with 18 new articles proposed. Most elections come down to a person, or a party, or a single choice: leave or remain in the E.U., legalize or criminalize marijuana. Ballot questions in the U.S. tend to focus on one provision, a rule change, an exception. But to ask an ordinary citizen to vote on a legal system and its outcomes? To essentially envision the future of government? It’s a tall order, and in the face of a difficult decision, most will latch onto what could be lost—the ability to drink alcohol, to wear the chador, to roam the streets undisturbed as you are. Bars, headscarves, mini skirts: these talismans of identity take hold, turn political, until winner takes all. Until it’s a referendum on the public itself.