Time to Party Like It’s 1989

Time to Party Like It’s 1989

Soviet Champagne in Ukraine

It’s the Christmas holidays in Ukraine and I curse my fate as I walk around a crowded supermarket, scanning shelves for a bottle of sparkling wine. I am on a mission: I have to buy a gift for Galyna, an elderly friend of our family.

“Should I get her a bottle of good Argentinian wine instead?” I ask my mother on the phone, but she is adamant: it has to be good old Soviet champagne, called Sovetskoe Shampanskoe, “Galyna wouldn’t want anything else on her table,” my mother says.

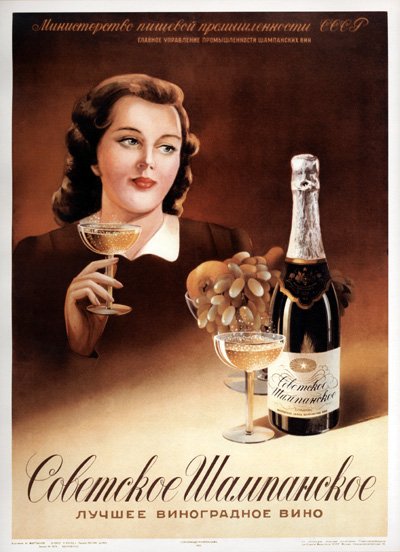

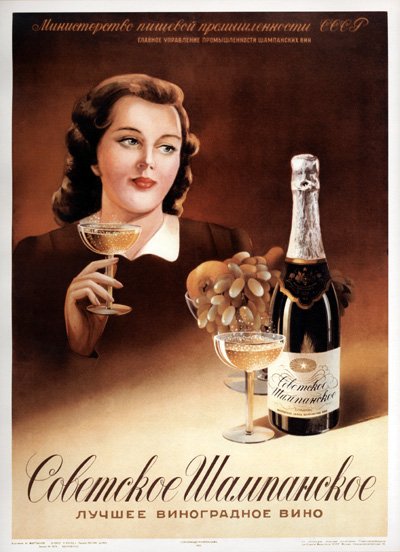

Costing an equivalent of two U.S. dollars, Soviet champagne occupies the lowest tier of the wine department. Wildly popular in Soviet times, it is now the preferred drink of those flat broke or nostalgic for the past era.

Before the Soviet Revolution of 1917, champagne was the drink of a privileged class, and the Communist party decided to make it accessible to workers. The winemakers were given the assignment to create a drink equivalent to French champagne but faster and cheaper in production. The result was Soviet Champagne: a sparkling wine produced in the span of one month. It was a blend of various grapes from Moldavia, Ukraine, Georgia, and Central Asia, processed in numerous wine factories around the U.S.S.R. using identical recipes.

The quality of Soviet champagne was low and gave its consumers terrible headaches. But walled from the capitalist world as the U.S.S.R. was, there was nothing better on the market. Bottles of Soviet champagne embellished every table during every celebration up until recently, when other kinds of sparkling wine became more accessible and affordable in Ukraine. The popular drink was often faked and one had to be careful not to buy a bottle of shampooed water.

After the fall of the U.S.S.R., Soviet champagne was produced in the ex-Soviet countries under old and new names. In Ukraine, the Kyiv Factory of Sparkling Wines produces the drink according to traditional recipes under its original brand name: Sovetskoe Shampanskoe.

When Parliament passed a de-Communization law banning Soviet names and symbols last year, the factory tried to save the brand and added just one letter to the drink’s name, turning Sovetskoe into SovetOvskoe. The change seems to be good enough both for the government and the older generation, sticking to its habitual festive drink.

Galyna is not a radical pro-Soviet babushka. Originally from Lugansk, in Eastern Ukraine, she is against Putin and the war in Ukraine. She enjoys the delights of a capitalist world, like supermarkets and the ability to buy a car or go abroad. But she is a bit nostalgic for the old times. “The Communists gave so much to Ukraine—such buildings, such factories—and now it is all in ruin!” she says. “And look, instead of bringing the country to order, they now spend money on dumb laws. Who needs a new street name when people have nothing to eat?” She finds it strange to see street and city names changed and the statues of Lenin demolished all over Ukraine just because they are a reminder of the Soviet past.

As we say our goodbyes, Galyna still cradles her gift of Soviet champagne and complains about her teenage grandkids, who don’t participate in family celebrations anymore. They also buy Soviet champagne for their student parties, they say, but only because it’s cheap.