A Small Political Thaw Anywhere Is a Victory For Us All This Year

A Small Political Thaw Anywhere Is a Victory For Us All This Year

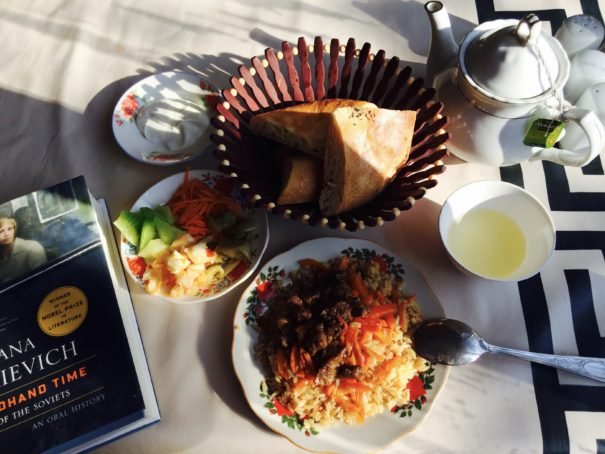

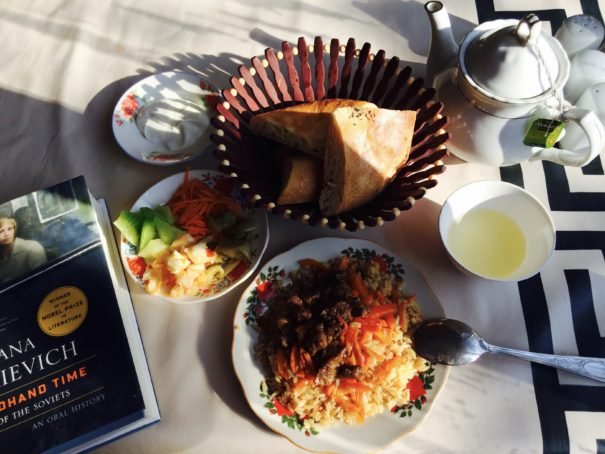

Osh in Dushanbe

The past year has been a grim one for the post-Soviet nation of Tajikistan. The president has seized more or less absolute, lifelong power; the only legitimate political opposition has been driven into exile; the economy’s been hit by a recession; and protections against warrantless search and seizure have been abolished. In comparison, America’s bad year seems almost picayune.

After a night of alcohol-fueled commiseration over the current, dismal state of affairs—and what are sure to be dismal-er times ahead—there is no better hangover cure than a plate of Central Asia’s soul food: osh, a succulent-sweet dish of rice, carrots, and beef or lamb, stewed for hours over an open fire and served with pickled vegetables, tangy yogurt, bread fresh from the oven, and a big pot of sweet lemon tea.

The dispute over where to get the best osh in Dushanbe, Tajikistan’s capital, is heated and partisan, but today I am in Oshi Khoja Rasul, a legendary oshkhona in a quiet residential street in the heart of the city. Here, the beef dissolves in your mouth after the first bite. The bread is yeasty and dense under its glazed crust. Muted winter sunlight filters through the branches of the plum tree in the courtyard into the low-ceilinged interior, with a wood stove heating cauldron-sized pots of tea, and age-stained carved wooden columns and paneling.

Traditionally, osh isn’t a breakfast food, but even Dushanbinci know that it certainly makes a great brunch, and by 11:30 a.m., Oshi Khoja Rasul is so full that patrons wend their way around the snug central hall looking for a seat, any empty seat, at the communal tables. I end up sharing with two taxi drivers.

I’ve come here today in honor of what may the only piece of good news Tajiks have heard all year: for the first time in 24 years, flights between Tajikistan and Uzbekistan will resume. The announcement came as the Tajik and Uzbek governments began to renew (some of) the diplomatic ties that were broken after the fall of the Soviet Union 25 years ago, potentially including an end to the strict visa regime separating the two countries. It’s a momentous occasion around these parts. No one really knows how many Tajik nationals are ethnically Uzbek, and vice versa, but it’s certainly a large number, and plenty of people in both countries have family on the other side of the border.

Osh is another—particularly delicious—cross-border linkage between Tajikistan and Uzbekistan. Three weeks ago, UNESCO declared osh part of the intangible cultural heritage of humanity, awarding the honor to both Tajikistan and Uzbekistan—a diplomatic move, considering both countries claim to have invented osh, and to have the best osh chefs.

Oshi Khoja Rasul is one of the many oshkhonas in Tajikistan owned and staffed by Uzbeks—a symbol of the indelible ties between the people of the two countries, regardless of any inflammatory rhetoric from their governments. And here, as day laborers and businesspeople alike mop up the last grains of rice from their plates with a crust of bread, mix pickled carrots with their yogurt, fill their neighbors’ teacups and pass the salt along the table, all that’s visible is the quiet pleasure of a meal heartily enjoyed in good company.