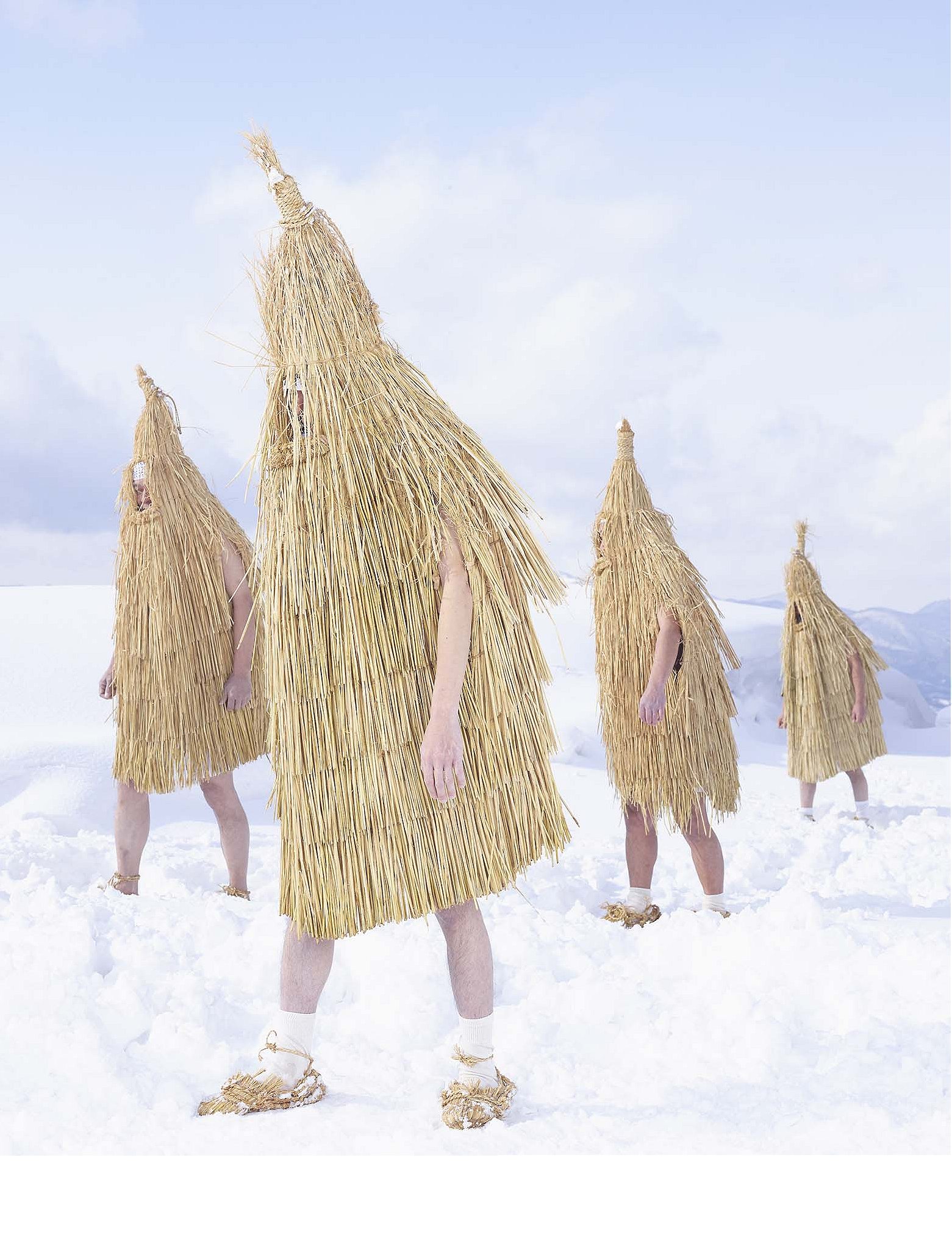

Meet the ritual figures invented by the Japanese to try to tame the elements.

The vibrant colors of Charles Fréger’s work caught my eye a few weeks ago as I walked up rue de la République, one of the main streets of Arles, a sunny city in the South of France. Inside the 17th Eglise des Trinitaires, striking portraits of human monsters big and small contrasted with the solemn, vaulted church ceiling. The photographer’s exhibition “Yokainoshima” is a highlight of this year’s Rencontres d’Arles festival, which celebrates the best of contemporary photography. And that’s exactly what draws you into Fréger’s documentation of ritual Japanese figures: just how contemporary tradition can be.

Roads & Kingdoms: Hi Charles, where are you calling from?

Charles Fréger: I’m in Rouen, I just came back from India yesterday. I was in Delhi working in schools on the idea of school transportation. In neighborhoods like Chandni Chowk, where you can’t navigate by car because roads are so narrow, people use school rickshaws to transport children. I was looking into the communities of Delhi through that lens. It’s a sort of portrait of India and its social classes, which are growing further apart.

R&K: How do you usually prepare for these projects? Do you have a team on location?

Fréger: Yes, I went with an assistant and I had three Indian assistants on location that had organized meetings with schools and that helped me contact certain groups. The preparation for each trip is much longer than the shooting time. We need to find the subjects but also the place, and then contact them and create a schedule, which takes time. I’m always preparing many projects at the same time, five or six trips that might or might not work out.

R&K: How much time did you spend on the project Yokainoshima?

Fréger: Not very long, I took five trips in two years. The book is called Yokainoshima, which means the island of yokai. A yokai is a creature that is strictly Japanese and that can be a monster, a ghost, even an object, and that shows up on Earth to poison people’s daily lives. It’s very complex, because some yokai are also divinities. The Namahage is a yokai, and also a god that descended from the mountains to bring a message and to scare children. The oni are demons. They are also gods. All of this is a question of how you consider each creature, how they are embodied, and what the context of the celebration is. “Yokainoshima” is not a real island. I came up with that title because throughout the project I always thought about being on an imaginary territory. We visited 20 islands, and we didn’t know what we would find on each. In a way, it’s the story of Japan. We see how figures and traditions that come from far away have migrated, how they’ve transformed, or how they created themselves on their own. There are things that resemble what you would find in Cambodia, in Korea, in China, but there are also things that resemble European masquerades. So it’s all very complicated.

R&K: You specifically looked at Europe’s winter traditions in your book Wilder Mann. Were you looking for the same types of celebrations in Japan?

Fréger: In Yokainoshima, I look at all the seasons. At first I started working on one tradition that had a strong resemblance to what I had photographed for Wilder Mann: the Namahage. That was my first trip, but when I decided to continue this project, I actually started with the summer. We are not in the same mindset of what I found in Europe—carnivals and masquerades. Japan’s traditions accompany the inhabitants of a town or of an island throughout the rhythms of life and of nature, and also remind them of their responsibilities towards the community. There is an educative element to them.

R&K: You had to work around quite a few restrictions on how and when you could photograph these traditions.

Fréger: Yes. Some groups allowed me to photograph them only on the day of the celebration. Others were most flexible, thankfully, otherwise the project would have taken 20 years. I never photographed during the festivals, though. I always defined the context myself, so the shoot would take place just before. My work was not to document the celebrations. It was to pick out figures I was interested in and to photograph them in my visual territory, a place coherent to me with all the subjectivity that implies.

R&K: How were you able to pick out the shoot locations so quickly?

Fréger: I just showed up an hour or two before, or the day before, and we would scout the surroundings. Depending on the figure, I would be looking for the sea, or a field, or mountains—it was very varied. Most of these groups came from small towns or villages so it was easy. One tradition was in the suburbs of Tokyo though, and we had to be a bit more creative. Preparation isn’t the most complex part. What was difficult was the weather and the willingness of people to get involved and to take time to do this, because it takes a lot of time.

R&K: Just putting on the costume must have taken a while in some cases.

Fréger: Yes, and that’s also why certain groups only agreed to be photographed during the festival; simply wearing the costume was complex. Some costumes are made with natural materials, and are very fragile. They were made on the day of the celebration, so in those cases we had to be there that day. It was similar for the straw men in Wilder Mann.

R&K: How were you able to see what the costumes would look like in advance? Had they already been documented in photographs or drawings?

Fréger: These figures are often used in villages as tourist draws, so there is a little bit of material—documents, drawings, photographs, pictograms. That’s how we were able to go: hey, in the prefecture of Fukuoka, there are these little black devils and then we’d go to find them.

R&K: We very rarely see their faces.

Fréger: Yes, because I’m interested in the character, and not the person under the costume. I’m interested in the embodiment, in the imaginary identity. That’s why faces appear very little. However, in Yokainoshima, much more than in Wilder Mann, the head is visible. People wear masks that don’t cover the entire face, so you’ll see the person’s ears or cheeks for example. These masks are different than ours. European masks often cover the face completely. We hide the hands and whatever gives the man away behind the costume. Here, I think there is a willingness to show that the man is still there, in control of the figure. People aren’t transformed; they are playing. What’s really apparent about Japan in this project is theatricality. In Wilder Mann, we were documenting the transformation of people, who became beasts. They never took off their costumes. Here, masks could be taken off at any time. It’s about fantasy and theatrics.

R&K: You’ve worked in Japan already, with your series about sumo wrestlers, “Rikishi,” and the one about the Seijinshiki ceremony. What did this new project teach you about the country?

Fréger: “Rikishi” was made in Tokyo and its surroundings for two years. “Seijinshiki” was made in Osaka and Kyoto. Here, I traveled throughout the rest of Japan and discovered something else entirely. I am the son of a farmer. My sister is a farmer. With Yokainoshima, I got to meet Japan’s rural people. It’s an aging population, which is very frustrating to me. Sometimes I think Japanese people think food drops from the sky. It’s so much more chic to sell robots and cell phones than to grow rice, but paradoxically, Japanese agriculture is fundamental. I saw a lot of fishermen that were 75. I saw 75-year-old women growing rice. There are no young people in the farms. So right now, we are arriving at a point where it’s crucial to ask questions like: what does it mean to live in Japan when 80% of the population lives in the cities and the countryside is deserted? The disconnect is so strong. In Japan’s cities, many people don’t know anything about rural life and what takes place in the countryside. When my book came out, people told me they knew about the Namahage, because they’re the most famous, but they didn’t know about 90% of these traditions.

R&K: Will these traditions disappear for good?

Fréger: I don’t think so. Traditions reappear all the time. Someone will always take over. Maybe that’s what I want to believe in, but these festivals are still important to people. Even in Europe, I went to tiny villages where people came back from cities or from other countries even, just to participate in winter celebrations. It’s a mistake to think that these traditions will disappear for good. There are many urban practices that go away without us noticing. For example, will we say tomorrow that graffiti has disappeared? Things evolve, they stop for a while, and then one day they reemerge. We accept that in the urban space, but in the rural space we talk about extinction. What really counts in the countryside is how many people will be capable of perpetuating the traditions. In cities, it’s not the need for people, but it’s the fact that things go so quickly that we forget them and we move on to the next new thing. All of a sudden, we’ll notice that no one is skateboarding anymore. And then years later, we’ll see skateboards again.

R&K: So you’re an optimist?

Fréger: No, I’m not an optimist, because I spend my time traveling to places that are more and more bruised. I don’t really believe in globalization, though. What I see is that despite this idea of a globalizing world, there are groups, there are regional traditions, there are practices that continue and that are being reinforced, even financed. What I’m most worried about is how the environment in which I travel is being destroyed and worn out. That worries me.

R&K: You’re taking about nature?

Fréger: Yes. I don’t really feel like an environmentalist, but just coming back from India, it really shocked me. And Japanese beaches are monstrous. We think that Japan is clean, but many of their beaches are real dumpsters. They’re covered with polystyrene, with fishing materials, it’s incredible.

R&K: What you are saying about globalization sums up your entire body of work.

Fréger: The people I photograph, the celebrations, the rituals and the practices, they all have one thing in common: community. The sense of having something in common with your neighbor. And in general, that also means having something in common against someone else. Identity would be vague without some sort of rivalry. If there wasn’t a soccer team against another soccer team, a club versus another, then there wouldn’t be communal stimulation. There is a strong energy in the idea of wanting to be together and create a common identity. We are told that we live in an age of individuality, but people are constantly on their cell phones, sending messages to each other. We have this need to be with others.

“Yokainoshima” will be on show until August 28th at Les Rencontres d’Arles and was published as a book in June 2016. You can see more of Charles Fréger’s work on his website and follow him on Facebook.