In a society that feels increasingly lost in life, love, and finances, a self-help industry booms

Shanghai, CHINA—

I found my self-help group through an Uber driver. In China, the car service’s drivers are often part-timers who have other occupations—hotel managers, entrepreneurs, housewives—each with his or her own reason for driving, but with the common desire of “going out and learning.” It’s an expression you hear often in cities or small towns across the country; in Chinese, the term “going out” can refer to traveling abroad, or simply going outside the home or family and into the real, tougher world.

This particular driver was particularly interested in “going out.” He told me that driving around the city allowed him to meet new people and have new experiences. “You seem like a curious person,” he told me. “You should come to my events. They’re full of people like you that like to learn about new things.” I wasn’t exactly sure what he meant by “events,” but after the short ride from People’s Square to Jing’An Temple we exchanged contact information on WeChat, a popular Chinese messaging app, and shortly thereafter I received a message about an event on what seemed like a talk on food and nutrition.

I wasn’t terribly interested in a class on nutrition, but from the driver’s WeChat profile I could see he was involved with daily events on an unusual mix of topics, ranging from investing to dating to weight loss. While these issues are sources of concern for many of us, in Shanghai they are the most important boxes to tick for anyone that wants to “succeed.” It’s common, in fact, to see online advertisements for workshops that offer similar help. Marriage agencies offer courses on dating mannerisms. On Douban, a popular social network platform, it’s easy to find emotional support meet-ups and study groups for young professionals on a variety of topics. I had attended a few in Beijing and Nanjing before, but this was the first time I had encountered one that seemed to cover all aspects of daily life. I was therefore curious to know the winning formula and decided to attend one of the talks the following week.

The desire for self-actualization in a hyper-competitive society like China is strong. It’s also increasingly difficult as inequality continues rising. China’s income distribution is, in fact, among the worst in the world; China’s Gini coefficient for income, which is used to measure inequality, was 0.49 in 2012. The World Bank considers a coefficient above 0.40 to represent severe income inequality; by comparison, the United States is at 0.41 and Germany at 0.3.

The idea of self-development is not new, but a legacy of Confucian culture, where self-development is required to foster the development of others, and therefores create a more “harmonious” society. What is new, however, is that in today’s context, the wish for self-development is driven by the need to succeed. As Eric Hendriks, author of China’s Self-Help Industry: American Life Advice in China, puts it, “Chinese urbanites are driven by the fear of losing out,” which is also why driving an Uber car to “go out and learn” is not so different from going out and attending a class on nutrition. The self-help industry, with its Chicken Soup For The Soul books and motivational classes, offers help to those in fervent pursuit of happiness and well-being. Hendriks estimates that self-help books account for 34 percent of all printed books in China—a total revenue of about $3 billion.

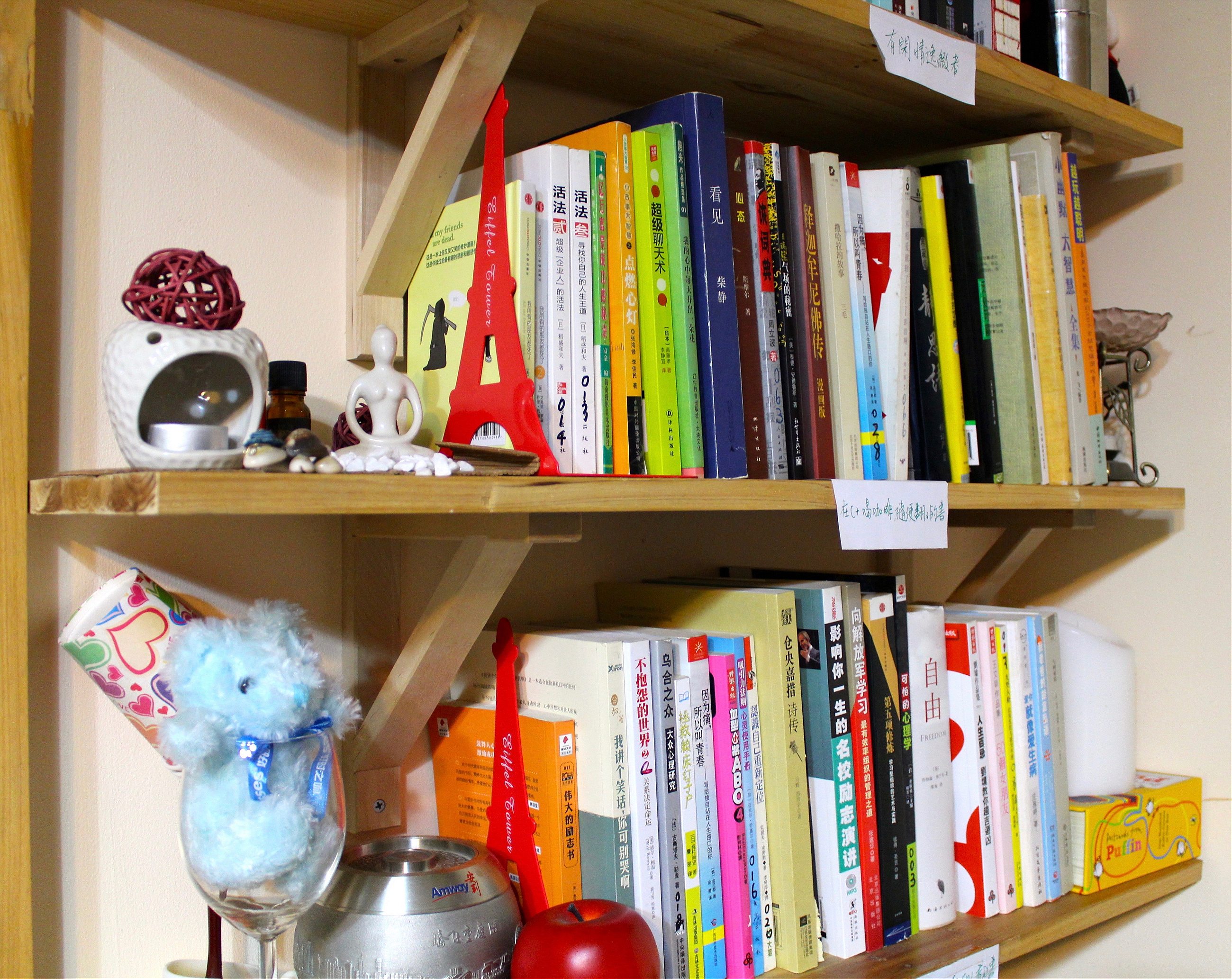

The class was in a lane house in the Former French Concession. I met my Uber driver outside the main entrance. He went by An Di, an auspicious name that translates to “peaceful guide.” He spoke softly in a controlled manner, pronouncing every word slowly as if I would not understand. He carried a large calendar where he jotted down his daily tasks. “Everyone in the group has one. It helps us feel better,” he explained. He told me that his group has been renting the space for a year and that the membership has been growing steadily. “This is a place for self-development,” he said proudly as he showed me around the house, which mainly consisted of one large room with an open kitchen. It reminded me of a playroom, with tables and chairs scattered around, buckets of colored pencils, shelves of books, and sheets of white paper piled on tables.

The group was about 30 people, some regulars, some new. They were mostly in their 20s and 30s and worked in a variety of professions, from design to advertising to IT and e-commerce. Most attendees were women, but an increasing number of men are joining as well, An Di told me.

The events are organized by a man they call Brother White, who is something like the members’ life coach. They credit him with getting their lives on the right path, one on which they are healthier, happier, and generally better people. The events are aimed at helping others achieve this level of well-being. In the last year, they have started sister groups in six cities, and plan to start many more. Brother White, who lives in Taiwan, travels to Shanghai every month to give two or three talks. On his last visit, the guru opined on the future of the economy, and women.

The choice of topics is consistent with the varied books that filled the room’s bookshelves—predominantly motivational self-help books with titles like Define Yourself and Pain is What We Call Youth. I’ve seen books like these all over China. Chicken Soup For the Soul volumes can be found not only in bookstores and libraries, but also on streets near university campuses and train stations. Dale Carnegie’s How to Win Friends and Influence People is considered a classic in China, and John Gray’s Men are from Mars, Women are from Venus is sold at virtually every book vendor.

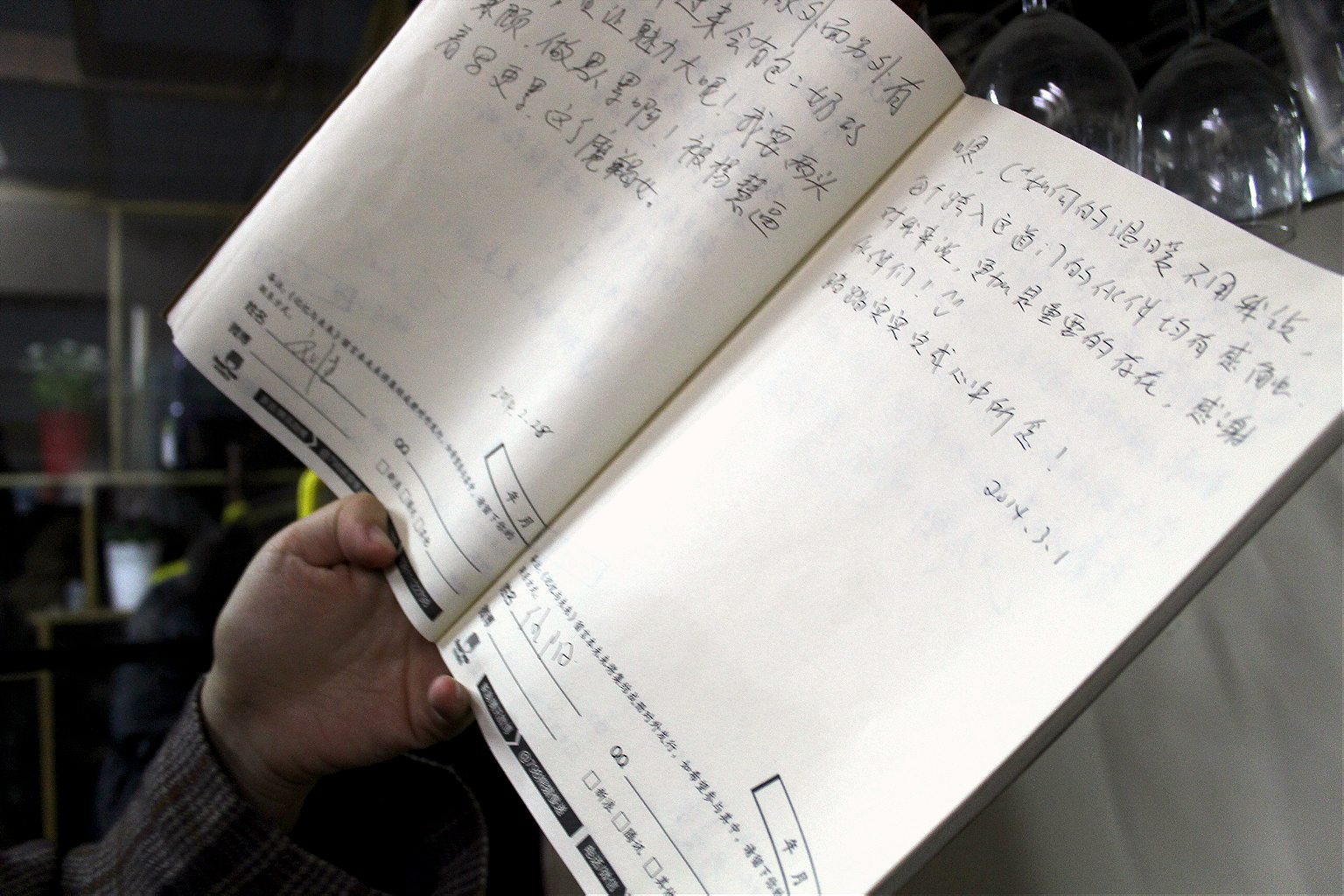

An Di, the Uber driver, showed me the group’s diary, a collection of handwritten wishes and motivational messages. “Writing down your thoughts and emotions can help you better yourself,” he told me. As we spoke, the room filled up and a young woman, who wore black clothes and a red shawl, introduced herself as the host of today’s class on nutrition. She invited us to address her by her English name, Isabel. I took my seat while we were asked to do a round of AA-style introductions—our names, blood type, zodiac sign, and what we hoped to learn or achieve. The group applauded after each introduction. One young woman wearing a flowery dress said, “I’m here because my motto is healthy, happy, and thin.” Another member, who recently got married, explained, “I want to improve myself, my family, and especially my husband!” Another member, who also hosts a weekly class on movies, said, “I didn’t realize I was unhealthy until I started coming here.” She added, “I am an entirely different person now.”

What followed was a series of do’s and don’ts that Isabel read out loud from a PowerPoint presentation she had put together. “Reducing foods containing carbs makes us stronger and energetic”; “Drinking water in small sips helps your body absorb it better”; “Avoid eating street food”. The advice was a mix of traditional Chinese medicine and food scares with an American twist. While everyone dutifully scribbled down notes, there was a group reading of a Taiwanese version of Let’s Eat Right to Keep Fit, a pseudoscientific book on nutrition from 1950s America that, I discovered later through a Google search, had been debunked for providing false nutritional advice.

At the end of the class, Isabel proceeded to demonstrate the efficacy of vitamin C supplements over flu tablets that she had bought over-the-counter. She poured water into two small containers, added red ink to both, and then dropped a vitamin C tablet into one and a flu tablet into the other. The first turned white and the second black. “And this is why it’s better to take vitamins rather than medicines when you are ill,” she concluded without elaboration, as everyone awed in a chorus.

As the class ended and the group moved on to prepare dinner, I reflected on what exactly these young women and men were getting out of the event. In a deeply uneven and highly competitive society such as China’s, I could understand how Brother White’s classes offered a solution to anyone pursuing well-being and happiness. It’s much less about learning what’s OK and not OK to eat, than developing the tools and support network to navigate the complex and stressful society out there. To “improve” or “heal,” as the group members describe it, therefore means to get back on your feet, follow your dream, and succeed.

The value of a class like the one I attended lay not so much in the quality of the information, but in its ability to help people craft knowledge based on the overwhelming amount of data around us. Choosing bits and pieces of nutrition knowledge from different sources, such as traditional Chinese medicine and American nutritionists, gives a sense of control over one’s life—even if the information provided is dubious.

But I still wasn’t totally sold. As I prepared to leave, An Di approached me to ask how I was feeling. “Confused,” I replied.

“That’s how all newcomers feel, but you’ll feel much better the next time you join us,” he said, before encouraging me to write down my thoughts in the group diary.