A quarter of India’s population was affected by a massive drought this summer. In the region of Marathwada, farmers are losing hope.

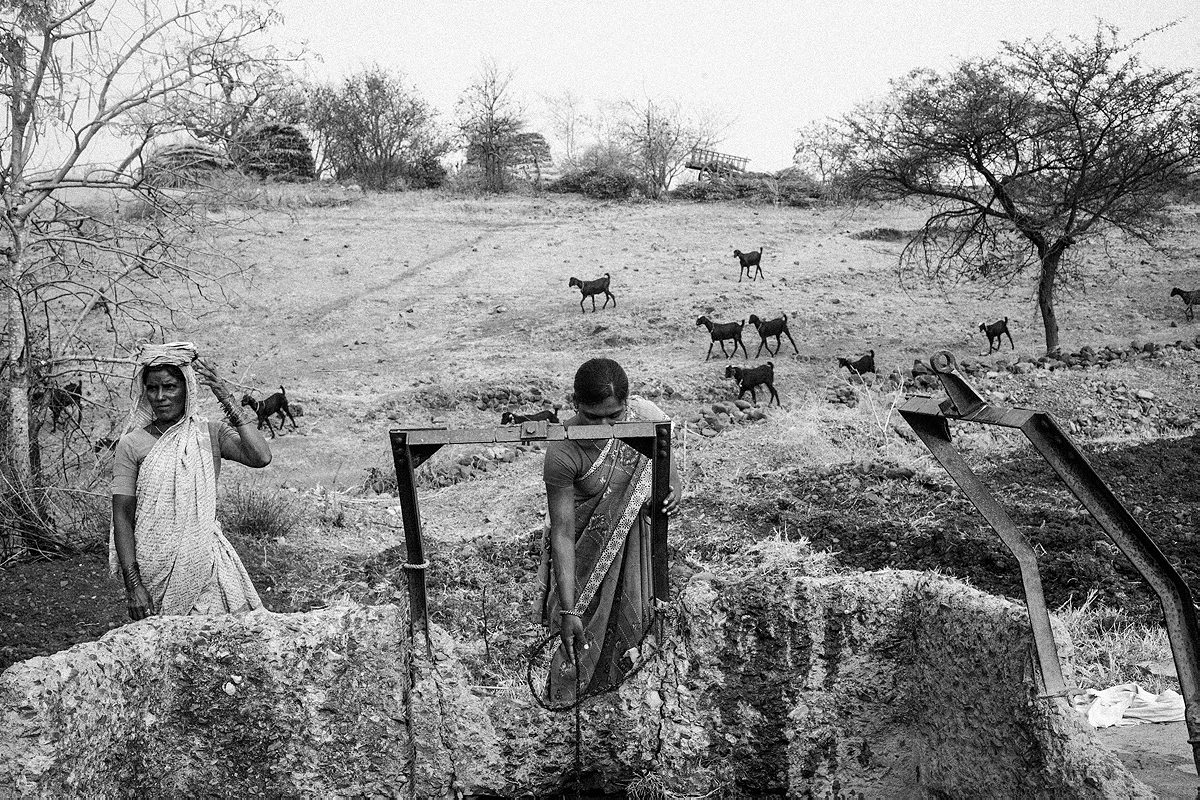

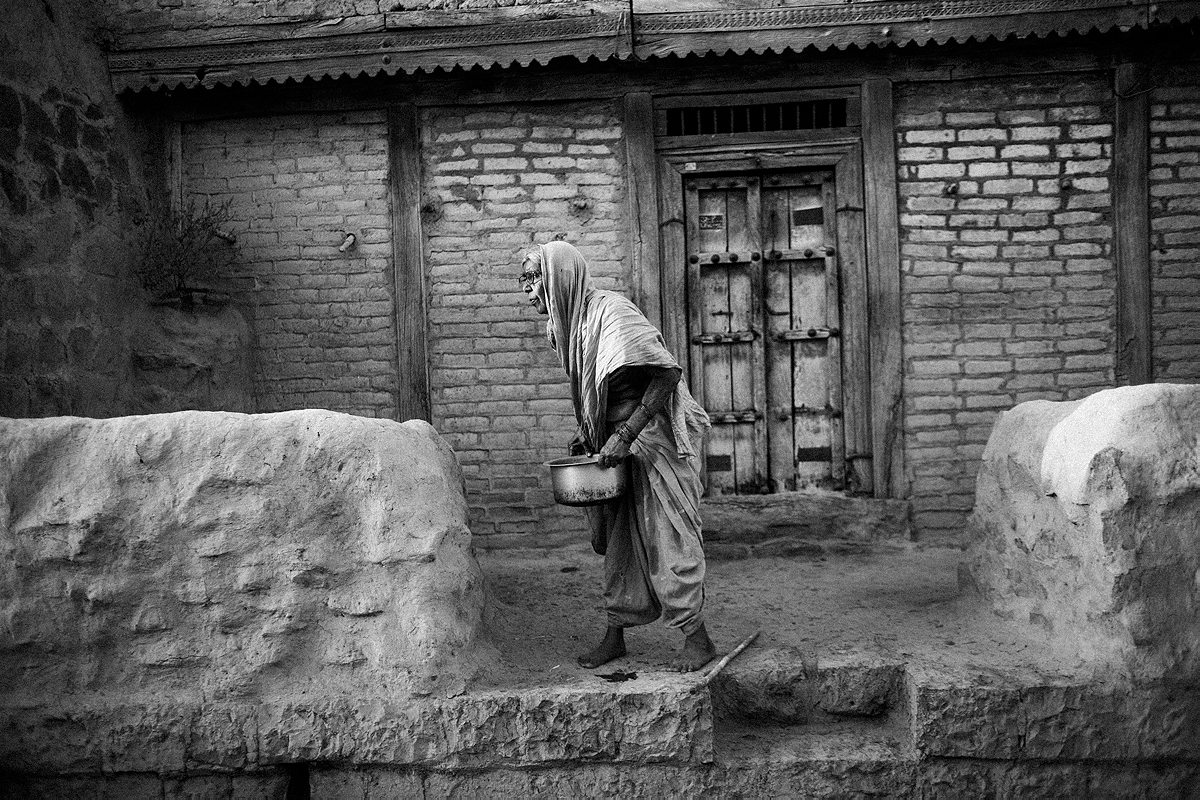

Over centuries, people in the rain shadow region of Marathwada have developed a lifestyle that emphasizes conserving water. After bathing their children, for example, it is not uncommon for mothers in villages to give the collected water to livestock or use it to water plants.

Sugarcane, a water-guzzling crop, isn’t well-suited to the arid landscape. Yet state-level policies have led to the establishment of 61 sugar mills in Marathwada, a region spread across 25,000 square miles in the western Indian state of Maharashtra.

With the promise of higher returns, farmers were encouraged to move away from traditional crops like sorghum, bajra, groundnut, and pigeon pea.

Today, the proliferation of sugarcane is only one of many factors contributing to the farmers’ misery. A terrible drought swept across India this summer, affecting more than 330 million people, a quarter of the country’s population. Among the worst hit was the Marathwada region, located 220 miles east of Mumbai.

Marathwada only received 49 percent of what is considered normal rainfall in 2015, with some villages receiving as little as 35 percent. I met farmers who are spending huge amounts of money to dig one well after another, hoping to tap into a much deeper aquifer that will save their crops.

As yields suffer and debts accumulate, many have been pushed to the brink and beyond: over 1,500 farmer suicides have been reported in the region since last year.

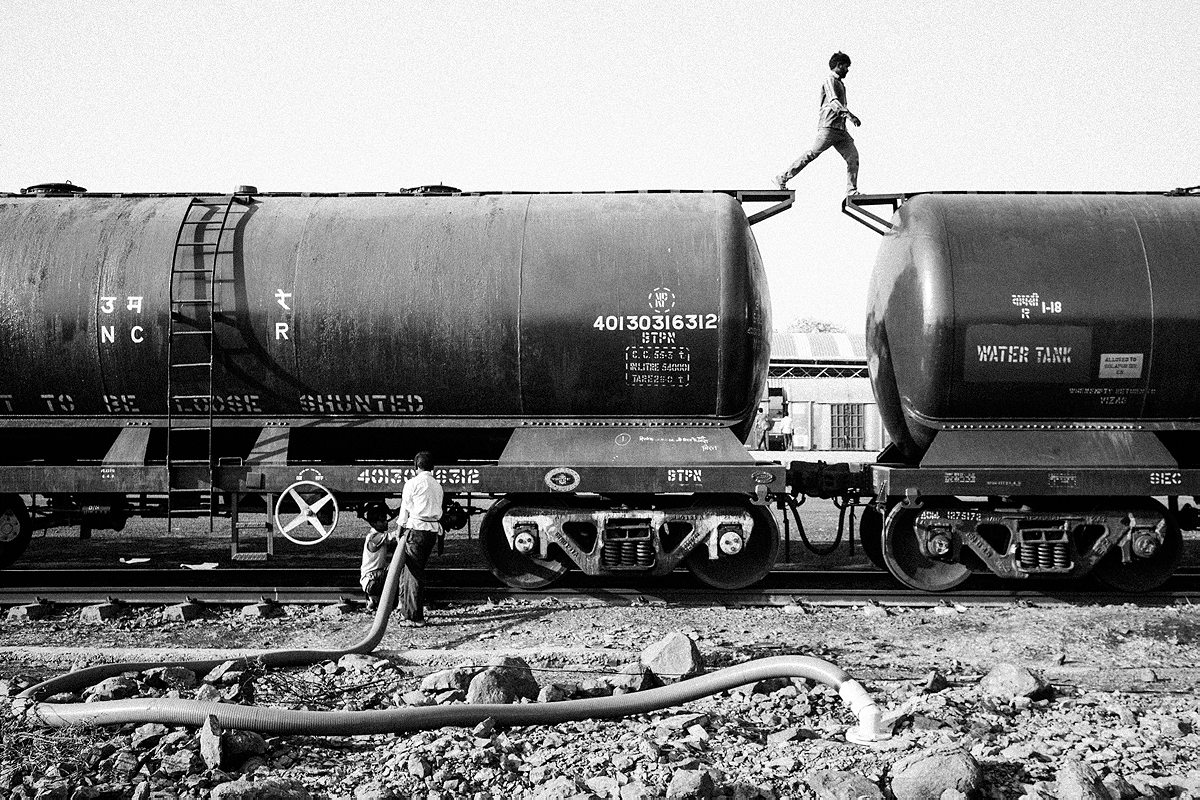

Facing a severe drinking water crisis, the state decided to ban the opening of new sugar mills in the region for the next five years. In the cities of Marathwada, scuffles frequently break out among those who must wait hours to get water from tankers. School exams in Latur, a major education hub, were moved forward so that students could return to their villages sooner and bring down the city’s water requirements.

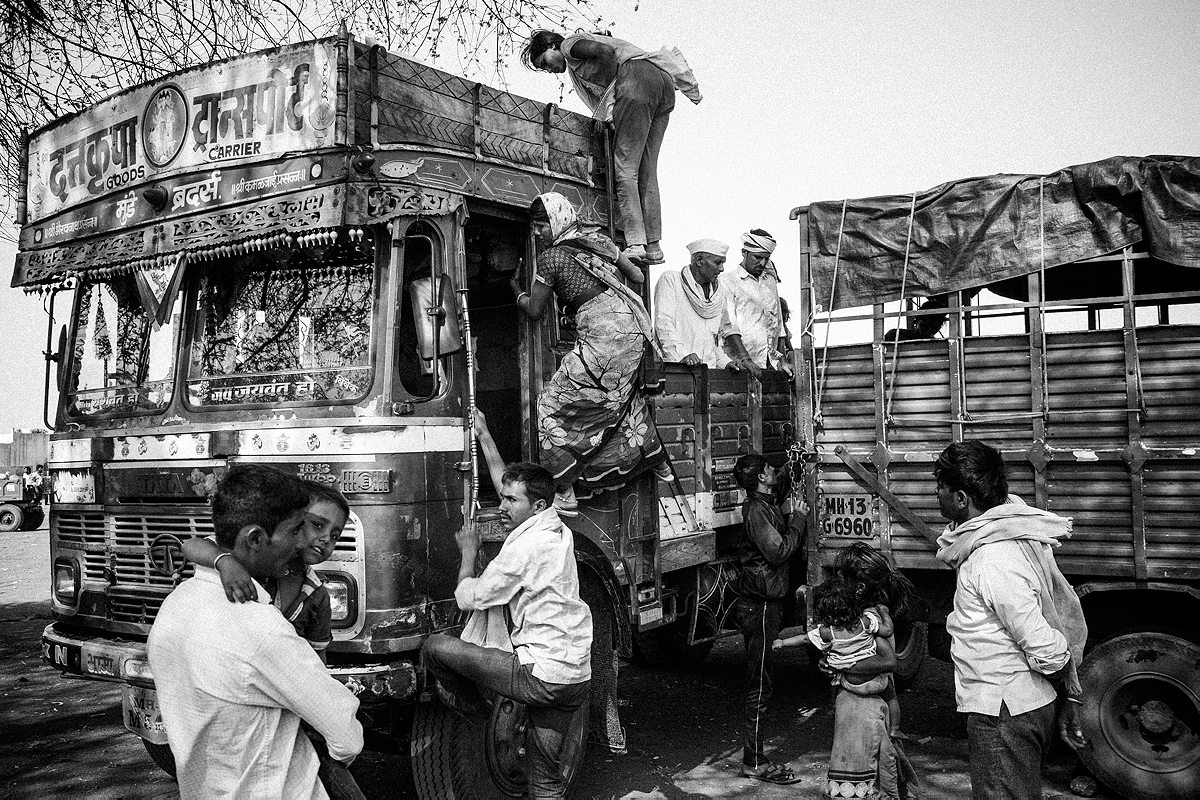

The lack of work in villages during the summer months has forced thousands of farmers and landless laborers to migrate to major cities like Mumbai, Pune, and Hyderabad. Madhukar Pawar, a 26-year-old farmer from Pimpri Deshmukh in Parbhani, is a first-time drought-migrant. He owns four acres of land in his village, but works in a Mumbai suburb for nine dollars a day, clearing drains in preparation for the next monsoon.

“It is well below my dignity to do such work but I don’t have a choice,” he told me. Others have found jobs at construction sites or sweeping the roads. They sleep on open ground and under flyovers, hoping to return home soon.