A photographer discovers Northern Nigeria through the women who write romance novels.

When Glenna Gordon showed Firdausy the picture she had taken of her, the young woman was disappointed. In the photograph, which is the first in Gordon’s new book “Diagram of the Heart,” a woman lies on a bed reading, while crisp light coming from the window behind her illuminates her neck, her feet and her arms. “It’s very dark,” Firdausy told her. “You can’t see my face.” Many of the photographs in Gordon’s book, which documents the lives of female romance novelists in Northern Nigeria, share this aesthetic: they are taken in the intimacy of bedrooms, where light and shadows create both closeness and mystery. “They definitely didn’t love all the pictures,” explains the 34-year-old photographer, smiling, adding the Nigerian women she met were used to “bright, shiny photos taken with a lot of flash of everybody standing up very straight and looking right at the camera.” She did take some of those too and printed them as gifts as she returned again and again to the city of Kano and its surroundings. “Diagram of the Heart” is her love letter to the women she met there. She spoke with R&K at our offices in Brooklyn.

Roads & Kingdoms: Can we start by talking about the title of the first one of these romance novels that you came across? It’s called “Sin is a Puppy,” which is just… great.

Glenna Gordon: Yes, the full title is “Sin is a Puppy that Follows You Home.” It’s actually one of the few Hausa novels that have been completely translated into English. Basically, I was going to Northern Nigeria for a mass wedding and I asked an acquaintance, Carmen McCain, who did translations for the book, what I should read before I went. She said this book by a Muslim woman who writes romance novels. I was really excited about it right away, so I went up for this wedding and also decided to start this new project. I ended up pitching something to a publication who said they were interested in running a slideshow, but I thought it wasn’t right for this. I knew I wanted to dig in deeper and keep working on the project, so I held off and I kept going back.

R&K: What was it about “Sin is a Puppy” that made you want to explore this subject?

Gordon: The fact that it so completely and totally defied my expectations, and that once I went there, the people I met also defied my expectations. You know, we have so many ideas of what places we’ve never been to look like and what people are like there and what’s possible, and the romance novels shattered all of these things at once, and that’s exactly what I want to do in my work. “Sin is a Puppy” is not a beach read that is going to be appealing to a mass audience in the U.S., but I felt really excited about the story and just about this whole movement.

R&K: What is the book about?

Gordon: “Sin is a Puppy” is about a woman whose husband takes a second wife, who’s a prostitute. He ends up kicking her out of the house. In the meantime, the husband runs a stall at the market where he has all of his goods and his money, and there’s a fire and he loses everything. The second wife leaves him and he’s forced to ask his first wife for forgiveness. All of the relatives encourage her to accept him and in the end, she does. It’s not the kind of ending that a Western feminist audience would think of as a powerful, but within the context of Northern Nigeria, their power relationship has changed and that’s really significant.

R&K: Who are the first people you met while researching this project?

Gordon: One of the first people I met was Rabi Talle, who I visited a few times in Northern Nigeria, and her picture is sprinkled throughout the book. When I met her, she was young, she was very feisty, unmarried, and I told her about my other project on weddings and she said my sisters and I are going to a wedding tonight, why don’t you come? I just felt like all of the stars were aligning, and that all I needed was right there. So, of course I wanted to keep working on it. Then I met a lot of other writers and I clicked with some of them more than others. The ones who I had stronger personal relationships with were the ones I visited again and again. The starting point was definitely the novelists and the novels, but I used that as a starting point but not an ending point.

R&K: Where did it take you?

Gordon: All over. I went to a lot of weddings, I greeted a lot of ladies, I went back and forth to Northern Nigeria a lot and I guess in the end it took me to this book.

R&K: What is the link between the weddings and this project?

Gordon: When I started the novelist project, at first I did very formal portraits of the authors and I took photos of the production of the books and the markets and the industry, but I felt like that wasn’t quite enough. I showed the work to friends and other photographers here in New York and everybody said I should reenact scenes from the novels, but that just never appealed to me. I never really wanted to do that, that’s just not how I work. But most of the novels are about marriage, I mean, that’s the context in which romance happens there, there’s no dating, there’s only courting within a family structure that’s very prescribed and formal. I had been going to weddings for a long time for my “Nigeria Ever After” project and it just made sense to keep going to weddings.

R&K: How does the romance novel industry function? Are the novels all self-published and sold at the same market?

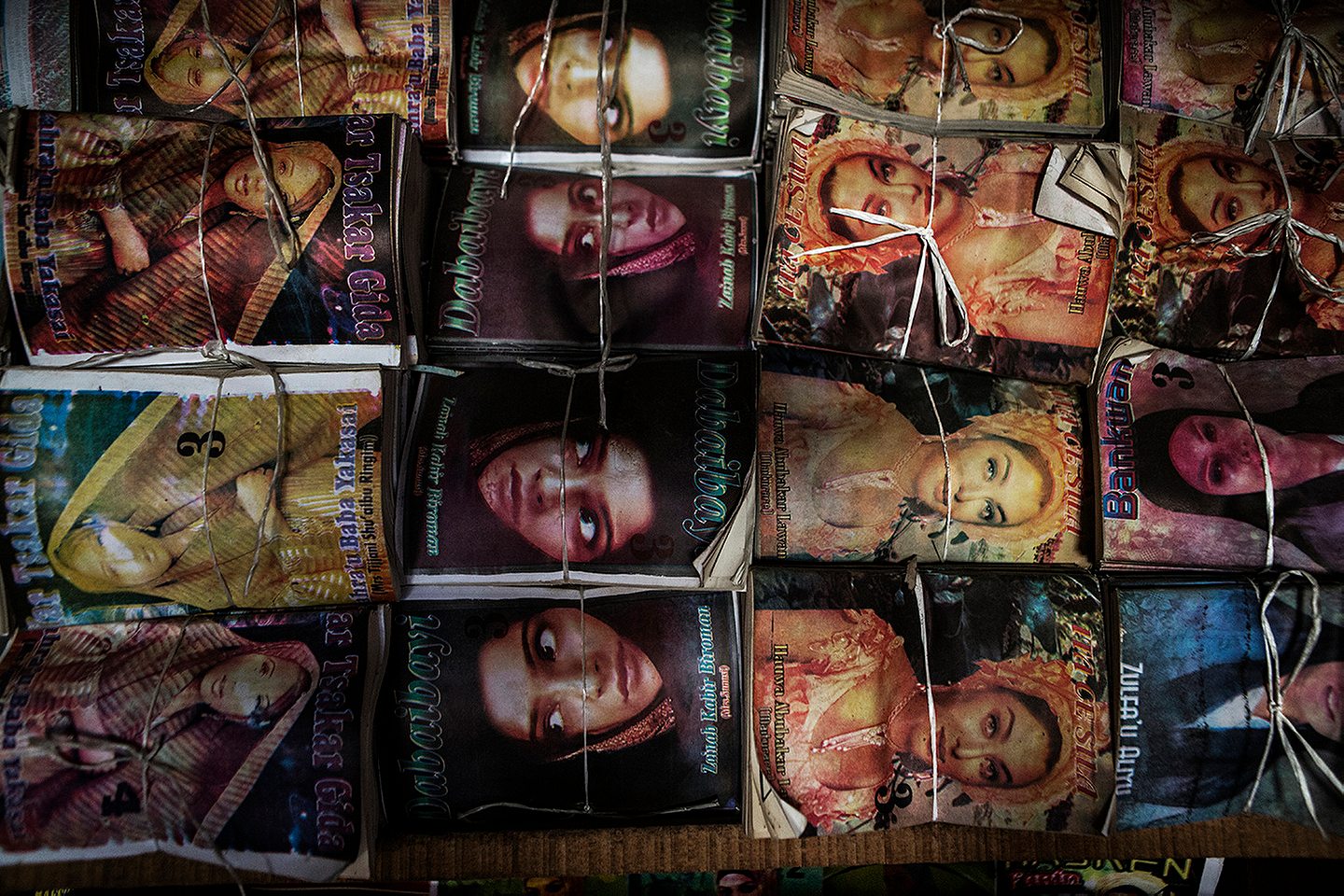

Gordon: Younger and less established writers have to front the money for their books and self-publish. They’ll take them to the market in Kano and then the shopkeepers will pay them when they’re sold. More established authors will work with publishers and can make a fair amount of money off of it. Most of the women write the novels by hand in small composition books and then take them to somebody who types and edits the text a little bit. Then the publisher will help organize the cover art and have them printed, hand-assembled, and taken to the market. There’s a big market in Kano where you can buy vegetables, used clothes, car tires, and books. They’re also scattered throughout Northern Nigeria and a bunch of countries in that area because Hausa is a language that’s spoken throughout the Sahel, which is the thin strip of land below the Sahara desert. It’s actually second only to Swahili in the number of people who speak it in Africa, so some of the books will travel quite far and go to markets in Niger and Burkina Faso and all over, but the center of the industry is Kano.

R&K: And in the production chain that you just mentioned, is it going to be women all along the way?

Gordon: No, editing and publishing is mainly done by men. One thing that was neat there was one woman, who’s one of the more prolific writers, she was super tired of all of these male shopkeepers cheating her and not giving her the full amount she was owed that she just opened her own shop. She sells mainly her books but also other people’s books, so there are women who take roles in the industry but for the most part it’s men.

R&K: What is the literacy rate in Northern Nigeria?

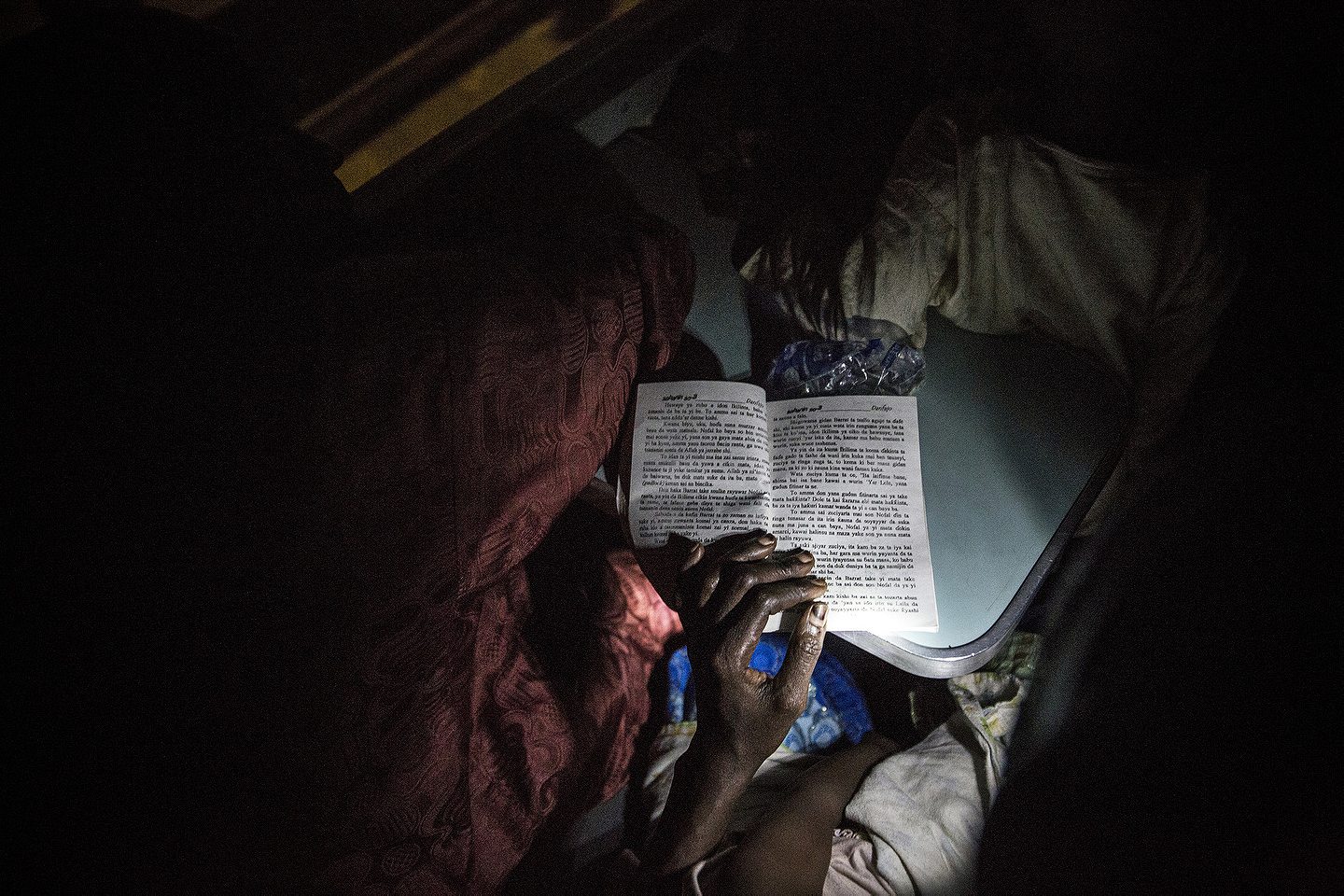

Gordon: I was never able to find a good number. Literacy in Hausa is actually higher than literacy in English, but I could never find a solid number. Definitely you’re going to see more middle class and upper middle class women reading novels, and you’re going to see more women reading them in cities than villages. But the last picture in the book is actually from an assignment for the New York Times Magazine, where I took a train across Nigeria. The train is definitely for people who can’t afford an airplane or a car or other transportation, and one night when I was walking up and down the train taking pictures, I saw an old Hausa woman reading a novel using her phone as a flashlight. I was really excited because I had seen city women reading them and middle class women reading them, but she was definitely neither of those.

R&K: What are other themes that are explored in these novels?

Gordon: There are a couple of writers who are super political. The woman who wrote “Sin is a Puppy,” a lot of her books speak out against child marriage. Jamila Umar, she wrote a book about a young girl who is trafficked to Sudan, and that was based on something that happened to her neighbor’s house girl. That’s the most extreme on the political end, and then some novels are just pure romance love stories like you’d see in Harlequin novels here. Others reinforce social norms. They’ll be about how to be a good Muslim wife, or how to accept the way your husband treats you, and those are certainly not subversive at all.

R&K: Can you talk about censorship and the pressure from local authorities to reign in this literature?

Gordon: A couple years ago, the person who was then the State Governor who’s now the Minister of Education in Nigeria publicly burned a lot of these books. He said they were leading to all sorts of moral indecency in the north and set up a system of censorship. As far as I understand, the books just became less racy. People are not fighting that and there’s not been a case of a novelist being arrested for writing a book. I think racy books still circulate a little bit, though it was hard to get people to talk about them because it is dangerous and it’s a very conservative place.

R&K: What did these novels teach you about Northern Nigeria?

Gordon: It’s funny because they tell you what’s important. There will be very extended descriptions about who greeted who and it will be like and he did not Salam her back and so when you read that sort of thing, you learn about what’s important to people and the way social relations happen. And again, I wanted to make pictures that were about what the novels were about. In the books there would be very long discussions of dowries, so that sort of piqued my interest and I would be on the look-out when I was at at someone’s house and I would ask what part of their furniture was their dowry. It just influenced the way I was taking pictures and what I thought of as a relevant picture. I mean, I was looking for things that were quieter and more atmospheric. It’s really easy to go to a place like Northern Nigeria and find a story about a woman who was captured by Boko Haram and raped and had a child and now is shunned by her community, and I feel like that’s sort of the standard photojournalist way to approach a region. I knew that it wasn’t really what I wanted to do. I do that quite often because at the end of the day, I’m a working photographer and I’m commissioned by newspapers and magazines, but I wanted to do something a bit different when I was doing this project on my own.

R&K: Right. Your project about the abductions of the schoolgirls by Boko Haram was also shot in Northern Nigeria. How did the two stories fit together?

Gordon: I had already been working in Northern Nigeria very consistently when the schoolgirls were kidnapped. It meant that I knew how to operate there, I had a network, I knew how to greet people, how to navigate these social cues, and it also meant that I really cared about the place. I had met tons of little girls who were the same age as these girls and I really felt like I wanted to do some work on it. I wouldn’t have done it if I hadn’t already been working on the novelists project, I wouldn’t have been situated to do it.

R&K: What does it feel like to work on such different types of projects in the same place?

Gordon: When I started out, I was doing much more narrow strictly photojournalistic work, but I didn’t find it very rewarding. I would do these stories about malnutrition, refugees, conflicts, and you know, I had this idea that there was a division of labor in this world and that my job was to take pictures and that someone else’s job was to disseminate the pictures and that someone else’s job was to create social change. Ultimately I started to feel like that system was broken. One of the main things that happened is that I was competing to take the best picture of a tragedy with other photographers, and I didn’t want to be in that race. It’s not that I’m not motivated by social justice, I absolutely am, but I also question the advocacy of photos to create change using that model. I mean, using that model, the photos I took of the schoolgirls were seen a gazillion places, they went viral, they were all over the internet, important people saw them, people saw them in Nigeria, people saw them in the U.S., and still nothing changed. So why am I doing this work? I’m not saying I shouldn’t have done that work, I’m very glad that I did it, but you know, I question the model that says that we’re supposed to take pictures of the tragedies that are happening because when we witness them, we are catalysts for change. To me that model is no longer working, and so as a photographer I just want to contribute something else to this world.

R&K: This project, of course it’s different and unique, but it doesn’t exist in a vacuum, it has political and social ramifications. What do you think it says about Nigeria today?

Gordon: When outsiders think about Islam, people think about ISIS, terrorists, Al Qaeda. And you know, there’s just as much variation within Islam as there is within Christianity. The more we know about the world around us, the more we’re able to fill in the blanks and not just project our own ideas. This doesn’t have the specific social justice platform that other projects I’ve done have, but at the same time, I hope that people who encounter this work have a slightly different perception of Muslim women living in Northern Nigeria, living in Africa, living around the world.