An impending peace agreement between the government and FARC guerillas draws new and old opposition.

GAITANIA, Colombia—

In 2000, Commander Wilson Ramirez, a senior explosives expert for the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia, better known as FARC, left his infant daughter on a stranger’s doorstep for them to look after. Ramirez, commonly referred to by his nom de guerre Teofilo, has seen her only a handful of times as he continues the armed struggle against the state. Today, his daughter, Laura, now 16, still lives with Orfany Neira, the woman who raised her as her own in this small village in the remote mountains of central Colombia, where Communist peasants inspired by the Cuban revolution took up arms 52 years ago.

But Laura and her father could soon be reunited for good. Despite missing a March 23 deadline, the guerrilla group and the government are closing in on a historic peace agreement that would end the FARC’s historic insurgency. Ever since the government entered negotiations with the guerrillas in 2013, a tense but steadfast truce has kept hostilities under control, giving way to a growing police and government contingent in previously impenetrable FARC strongholds like Gaitania. But the agreement has detractors as well as proponents on all sides.

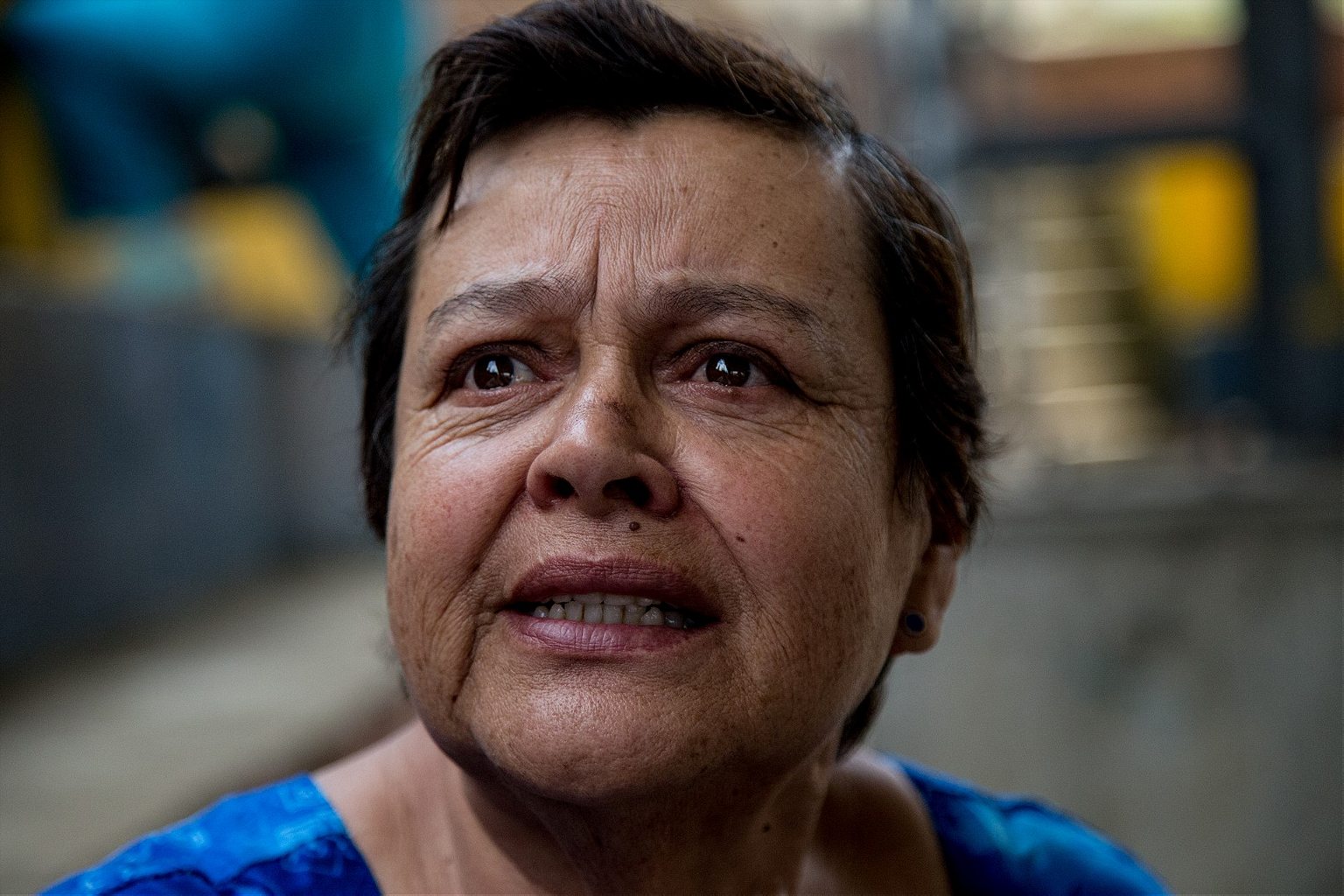

Two years ago, military police stormed Neira’s home, detained her for alleged FARC ties and sent Laura to a home for children in Bogotá. Neira was held in prison on terrorism charges that were eventually dropped, but not before both her physical and mental health critically declined. Fighting back tears, Neira tells us: “The FARC never once harmed me. It was the state who kidnapped me, humiliated me, and destroyed my life on a lie. I want justice, but even then I don’t know if I’ll ever find peace.”

The FARC’s insurgency spread across the country as the group fought a half-century-long war against the government, the military, drug cartels, and state-sponsored paramilitaries. From mountain encampments the FARC governed vast swaths of rural Colombia. But years of successful military offensives and desertion wore down the guerillas, paving the way for negotiations. Although recent polls suggest most Colombians support a peace agreement, the violence carried out by both the FARC and the state has been difficult to forgive.

The state’s presence in Gaitania could allow for demobilization areas for FARC soldiers transitioning into civilian life—after they hand in their weapons and formally abandon armed struggle. But as the government and the FARC debate the fine print of their accord, targeted population centers remain leery. Many locals wonder: Can the guerillas, who imposed their will with impunity for a half-century, be trusted?

The peace agreement wouldn’t change just the political landscape; it would also disrupt the status quo of the criminal underworld if FARC is compelled to renounce the production of coca paste. The FARC has long been financed by criminal enterprises, notably kidnappings and extortions, which the group justified as “contributions” to the struggle. It was in the late 1980s that the guerrillas entered the drug trade it once fought, leading to a financial windfall that persists to this day.

“The FARC are thugs,” says Octavio Varon, a rural day laborer from Gaitania. Last December, Varon and his wife and children were forced to flee their home after a FARC militiaman threatened to kill them if they remained in the village. Wilmer Geraldo, a local FARC officer, attempted to extort Varon, demanding a sudden payment of $600 for his protection. When Varon refused, Geraldo stabbed him repeatedly in the neck and left him for dead. Varon survived and paid the extortion money to save his family’s life. The family pawned their car, paid FARC, and fled with whatever they could carry.

Three months later, they’ve returned to Gaitania looking for reparations at the behest of a state-appointed conflict resolution attorney who set up a meeting with Geraldo. Varon was left significantly mentally impaired by his injuries, leaving his wife, Yuliana, to support the family. “We’re terrified to even be here, but if we don’t get our money or our car back we won’t be able to afford food for our kids,” Yuliana says as she cradles her youngest boy.

Geraldo never showed up for the meeting.

In Matallana, a crime-addled slum in the central Colombian city of Ibague, some 125 miles from Gaitania’s winding mountain passes, Sgt. Acevedo of the Colombian Army, who refused to give his first name, denounces a peace agreement with the guerrillas. “They’re narco-terrorists!” he cries. “It’s a disgrace that the president even shakes their hand.” His outburst comes during a community outreach program offering access to state-sponsored lawyers and health-care providers guarded by the Army’s Sixth Brigade. Their goal is to improve the state’s standing in a neighborhood better known for prostitution and drug-running gangs.

The end of five decades of fighting has left the military at an existential fork in the road. “Some of us are ready to support a coup if necessary against Santos,” says Acevedo, referring to Colombian President Juan Manuel Santos. “It starts with a peace deal and political power. Then we have a FARC government. Eight years later we’re the next Venezuela.”

Prominent conservative voices, some of whom describe President Santos as naïve, share Sgt. Acevedo’s view on the peace process. They support what’s called Uribismo—the militant right wing, anti-guerrilla ideology inspired by former President Álvaro Uribe Vélez. In Medellín, Colombia’s second city, Uribismo thrives. “It’s not a peace accord, it’s a surrender,” says Alejandro, a prominent real estate developer who withheld his last name out of security concerns, during Sunday brunch with his family at an upscale creperie.

“I grew up in a country where atrocities were the norm. The FARC put a whole village into a church and blew everyone up,” Alejandro says, referring to a massacre in Bojayá where 119 civilians were killed. “For those people to cruise into politics without spending a single day in prison is maddening.”

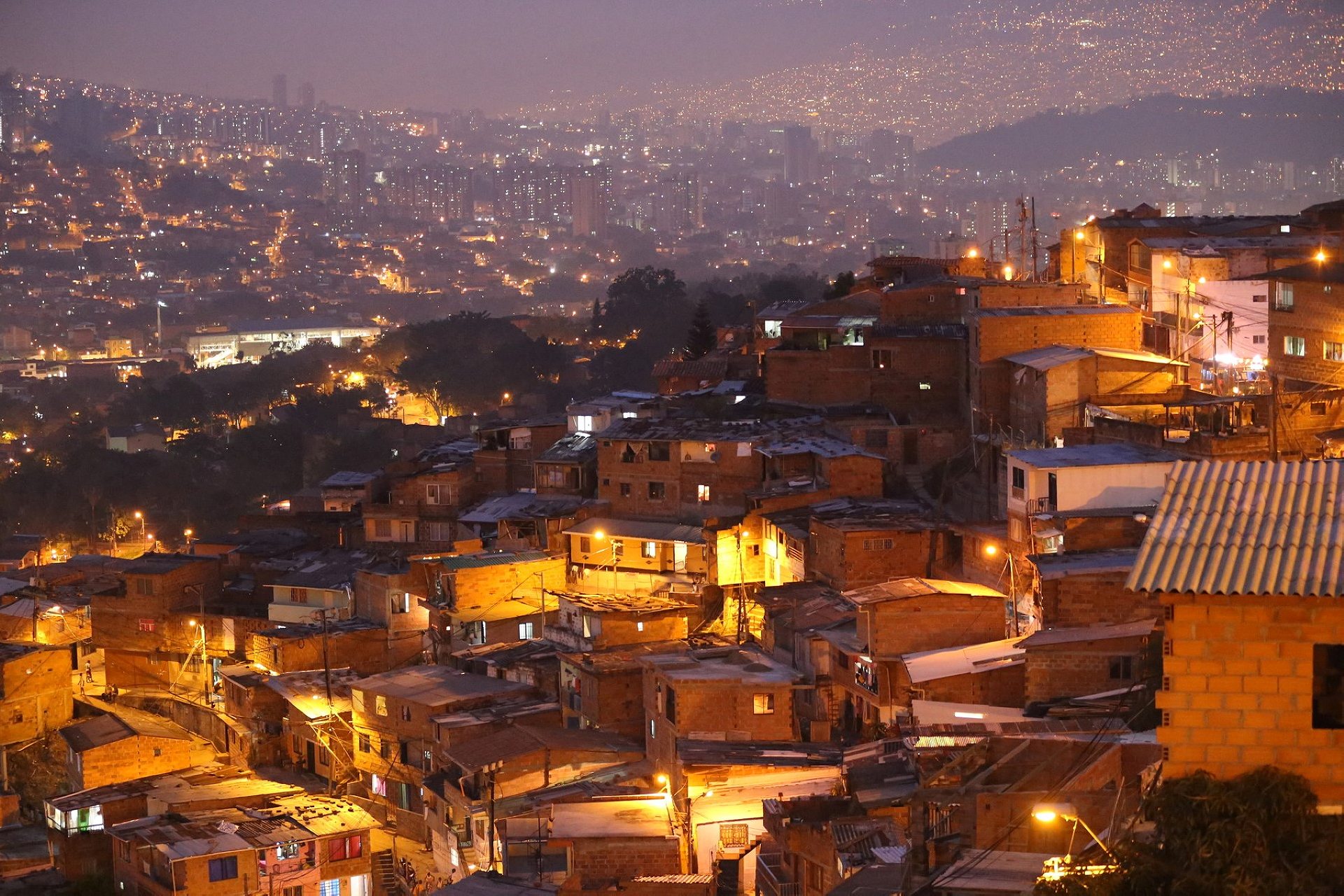

Not far from the neat streets of Medellín’s shopping district up the densely populated sloping hills that surround the city, the urban theater of Colombia’s civil war still rages.

“It’s a micro war. It might be less ideological than 50 years ago, less intense than a decade ago, but it’s never really ended,” says Jhol Ciro, a youth activist with Casa Kolacho, an organization that fosters violence prevention through the arts, as he stands at an outcropping high over the tight-knit network of alleyways and graffiti-coated single room houses of Medellín’s Comuna 13.

Ciro warns of the slow creep in violence against pro-peace community organizers by feuding apolitical gangs affiliated with offshoots of the demobilized paramilitary forces. In March alone, five activists were slain and countless more grassroots organizers were forcibly displaced by the imminent threat of violence.

More surprising is the apparent nostalgia for paramilitarism, despite the groups’ well-known penchant for violence. Graffiti pining for the paramilitaries’ return is popping up across the city walls and public spaces of Colombia. It’s something Ciro cannot comprehend: “It’s bewildering that people would rather have the paramilitaries back instead of peace.”

Across the city in the Comuna 8 district, Ciro finds an unlikely ally in Joaquín Ramírez, the former commander of the vicious Cacique Nutibara bloc’s anti-guerrilla operations, who is now a peace advocate.

“All my life I’ve seen people fall dead around me,” says Ramírez, a soft-spoken man of 42 years. “I used to hunt men down and neutralize them with chainsaws and long rifles because that was our life. The violence made us evil.”

Ramírez was forced into the conflict at 13 when he lost his family to a freak landslide that devastated Comuna 8. Armed groups exploited the chaos and established a foothold in the mountainside slum. Homeless and orphaned, Ramírez turned to the squadrons of paramilitaries to survive a city in turmoil.

In the campaign to cleanse Comuna 8 of urban guerrillas, Ramírez climbed up the ranks. “I thought I was one of the good guys in this absurd movie,” he says. Now he looks back with despair on the violence he caused that helped create the current climate of violence. “We wasted so many years of our lives in senseless violence. Shooting at each other from hilltop to hilltop. We thought we were defending people—it was a lie we told ourselves. We were all sinners.”

Just as the FARC are attempting now, the paramilitaries negotiated a peaceful end to their violence in 2003. It was not a seamless reintegration; his neighbors feared and ostracized him for his bloodied past. To make amends, Ramírez raised a now-beloved peace garden in the heart of the district he once terrorized. Surrounded by whimsical sculptures of anthropomorphized fruits and vegetables, he spends his days preparing flowerbeds and preaching compassion.

Ramírez urges Colombians to abstain from cynicism and to reconcile with the FARC. He insists the alternative is worse. “All of us are victims of this war one way or another. I caused this community so much anguish and yet they still forgave me,” he says. “Through reconciliation, I was able to become good again and go from being an aggressor to a peacemaker.”