There Is Much Warmth to Be Found in Shared Memories and Shared Drinks

There Is Much Warmth to Be Found in Shared Memories and Shared Drinks

Becherovka in Northern Slovakia

Slavs are cold and dark, at least according to stereotypes. But I know from growing up with my father, Igor, that below that icy exterior lies warmth and nostalgia.

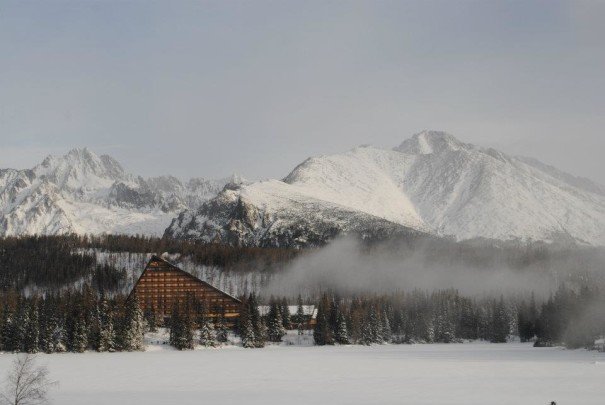

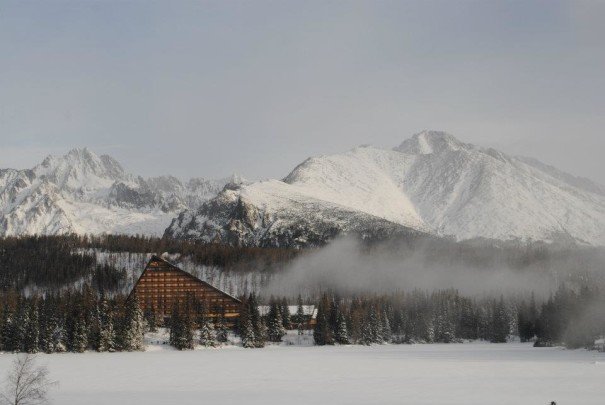

My family hails from the former Czechoslovakia and for a short time, we lived in Poland. Driving to the Tatras for ski trips became a source of solace during the long, tortuous winter months in Warsaw. Surrounded by genetically familiar faces, I would sit in a cabin with my family on the periphery of a glacier lake in Northern Slovakia.

It never takes me long to decide that I’m going to dive face-first, mouth-open into a big plate of bryndzové halušky. I could call it ‘Slovak mac and cheese’ if searching for a gross Western comparison. But that would be sacrilege. Halušky is composed of small potato dumplings, enveloped in a mild, yet slightly tangy, rich sheep cheese. Over the cheese is a layer of bacon and the remaining grease. The oil pools and glistens and when met with a cold beer, one experiences a most sublime sensation, which only cheese, bacon fat, and booze can create.

However, as crucial as melted cheese and fatty meat are to any post-skiing ritual, true salvation comes in the form of an herbal liqueur named Becherovka. If a drink could be the microcosm of a culture, this would be it.

To an outsider, it may taste too strong and complex at first, but if you

have enough of it you become enraptured by its bitter beginning and partial to its sweet undertones. Much like a first encounter with a Slav. As my father told me, it’s “part of our fabric.”

My first shot of Becherovka was around the age of nine and was handed to me by my father in a frosted shot glass on the side of a mountain. According to Igor, it was meant to “lubricate my muscles” for the day of skiing we had ahead of us. Even now, the smell of those mysterious herbs brings me a sense of comforting disobedience. A memory of mischievous bonding with my father, who used to whisper under my hat, “don’t tell mom.”

In the cabin, the shots of Becherovka began to slow the passing of time. My increasingly relaxed father requested a song (he really only ever relaxes in the presence of skiing and digestives). The small band—made up of a violin, a guitar, and an accordion—played a folk song that every Czech and Slovak grew up hearing. I remembered twirling in circles to that song as my babi sang to me. I could feel each pluck of the chords in my genes. I saw the russet faces of those around me soften as the violin wept. Both my father and mother had started to cry, and they weren’t the only ones.

Maybe everyone was fueled by copious amounts of beer and the soothing fire. But there is no denying that the magical liqueur progressively chipped away at the frigid exterior of my fellow drinkers as the ice encrusted on their boots was simultaneously melting under their seats.

There is much warmth to be found in shared memories and a generous amount of Becherovka.