By documenting the Soviet veterans of WWII, a Ukrainian photographer finds uneasy parallels to the current war in his country.

Victory Day, Moscow. To mark the 70th anniversary of the end of the second World War, Russia stages a massive military parade across Red Square. On the program: over 16,000 troops, 200 armored vehicles and 150 aircraft. It’s the last major anniversary that many veterans will be alive to witness, yet all eyes are on the empty space around Vladimir Putin: Western leaders have chosen to boycott the event in protest against Russia’s actions in Ukraine.

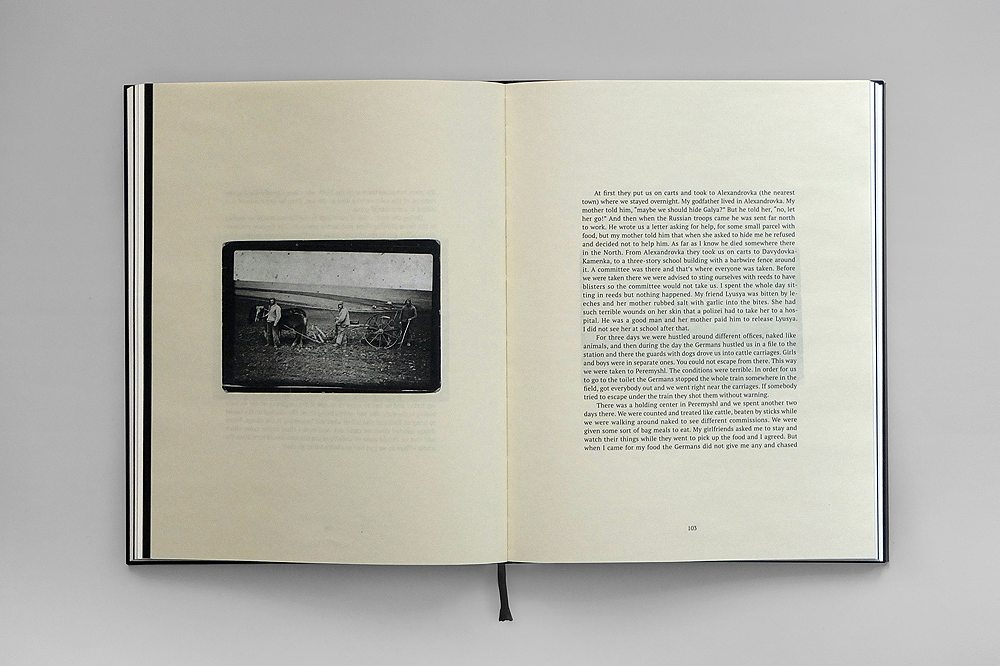

World War II was devastating for the Soviet Union, resulting in the deaths of an estimated 26 million people, including 8.7 million soldiers. Nearly every Soviet family lost someone. But the 9th of May display of military strength amidst the spiraling crisis in Ukraine was a stark reminder of how quickly war can cloud Europe. “We should remember the horrors of war and our history,” says Ukrainian-born photographer Arthur Bondar, who spent the last five years traveling the region to meet WWII veterans before they die. His book, “Signatures of War,” is a tribute to their sacrifices as well as a duty of remembrance for the generations that follow. He joined R&K from Moscow.

Roads & Kingdoms: How much did your family speak about WWII before you started this project?

Arthur Bondar: We didn’t speak much about this topic at all. It was quite hard to bring up because it’s such a painful page in the history of every family, especially in Ukraine, where I grew up. During my childhood, my brother and I spent summers at our grandmothers’ homes. I remember them telling stories about the war. When my maternal grandmother died, I realized how many questions I hadn’t asked her. It was the main reason I decided to start a project about the veterans of WWII. That was five years ago. At that time, I was 25 years old and everything I knew about WWII came from history books. I was very curious to meet real people who had lived through the war while they still alive.

R&K: Were you looking to answer questions about your own family?

Bondar: I never tried to find stories that were similar to my grandmother’s. We all share the same history, but each veteran has his own unique experience and life story. I was interested in the whole generation that went trough the war. People who lost their friends and came back alive to start a new life. I think that generation was much more human and honest than we are. They have very different values than we have today. I admired every veteran that I met during these five years.

R&K: How did you find them and what were the conversations like?

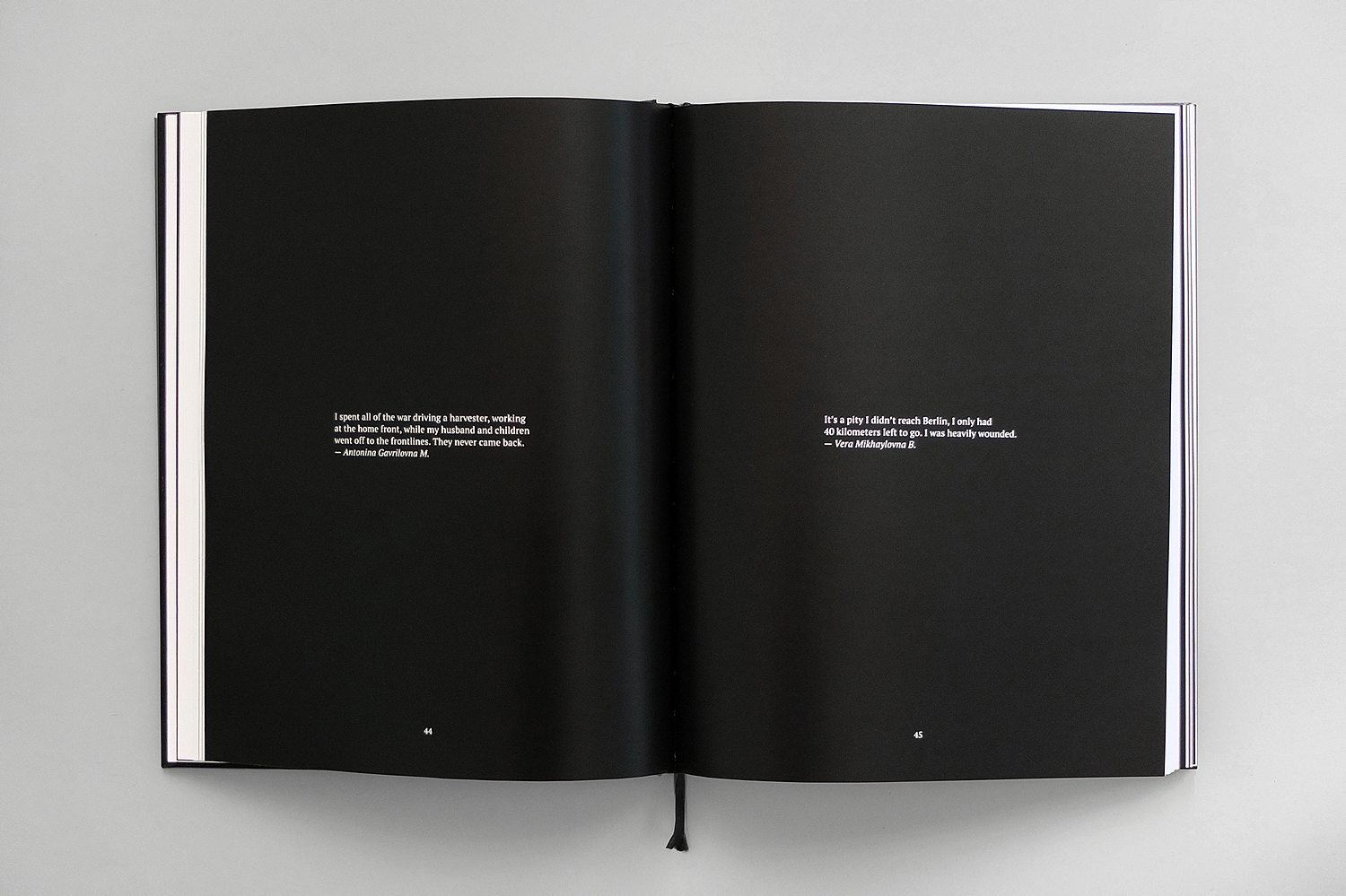

Bondar: There is such a lack of communication between veterans and the rest of society. Veterans usually speak either with their relatives or with other veterans. Their circle of communication is very small. It wasn’t difficult to find them. When I asked if they had friends who were also veterans, they would give me a huge list. I wanted to just open my heart and be really interested in their destinies. They told me their life stories, their names, when they experienced war for the first time and what happened after that. They told me their memories and feelings about war. It sometimes lasted five to six hours because nobody had ever asked them these simple questions. Our government and most people only remember veterans during Victory Day, on the 9th of May. Just one day of the year. It’s such a pity.

R&K: How many people did you photograph, and where did you travel for the project?

Bondar: I photographed close to 80 veterans. All of them were born in the Soviet Union and fought for the Soviet Union, so I consider them citizens of the former Soviet Union. I started the project in Ukraine in 2010 and was shooting there for three years. There, I met veterans of different nationalities who had stayed after the war: Russians, Kazakhs, Belorussians, Moldovans, Jews and others. I covered nearly the whole territory of Ukraine, including small villages and towns. I thought in those days that the project was finished. In 2012, I moved to Moscow to live with my lovely wife Oksana Yushko. When the latest events in eastern Ukraine happened, I understood that I needed to do something that would unite people, not divide them. I needed to say something about peace. So I continued my project in Russia. I wanted to show that we are all the same. People suffer on both sides of the frontline. There is not one truth in this war, and we will not have a winner. All of us will be losers.

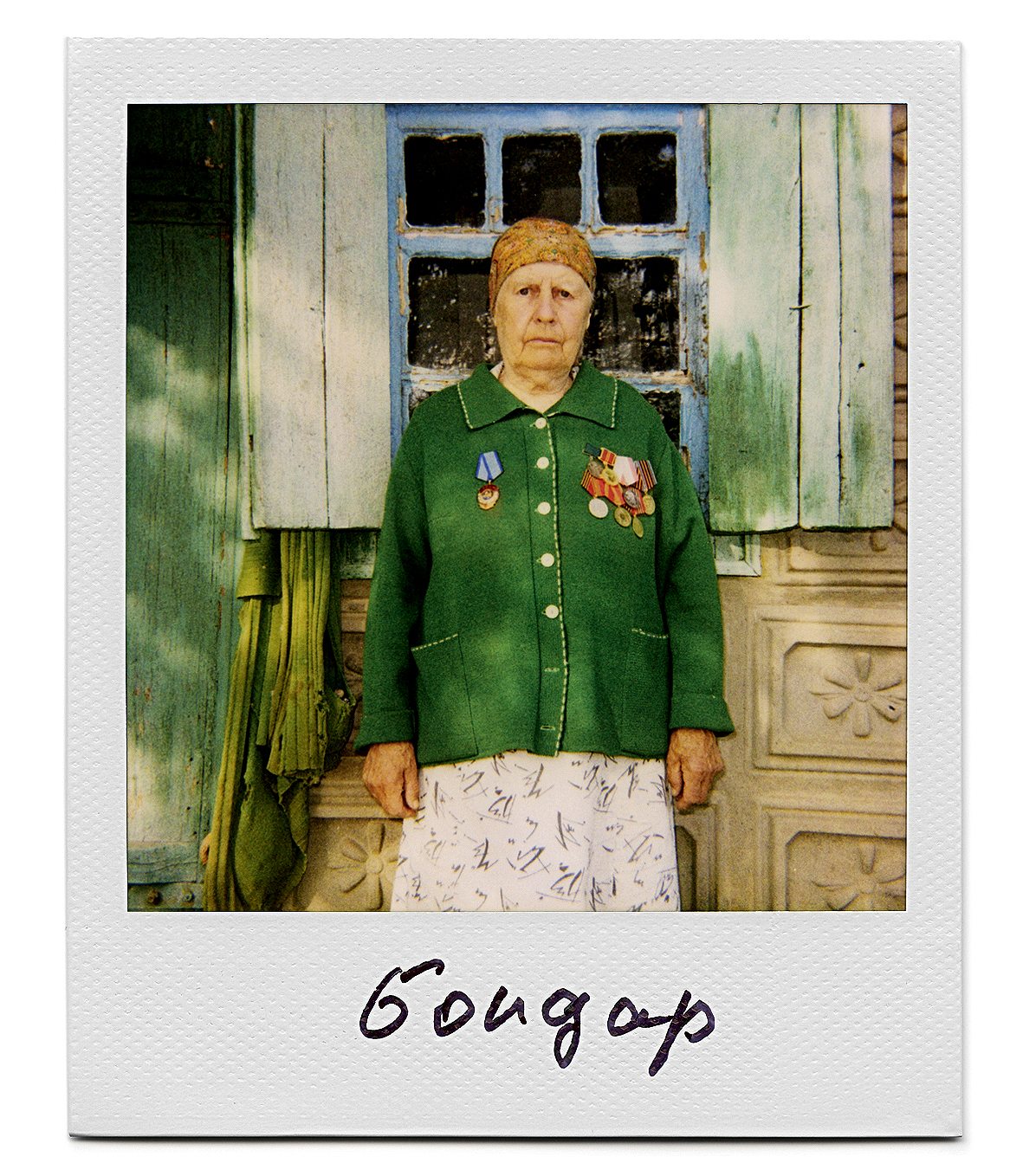

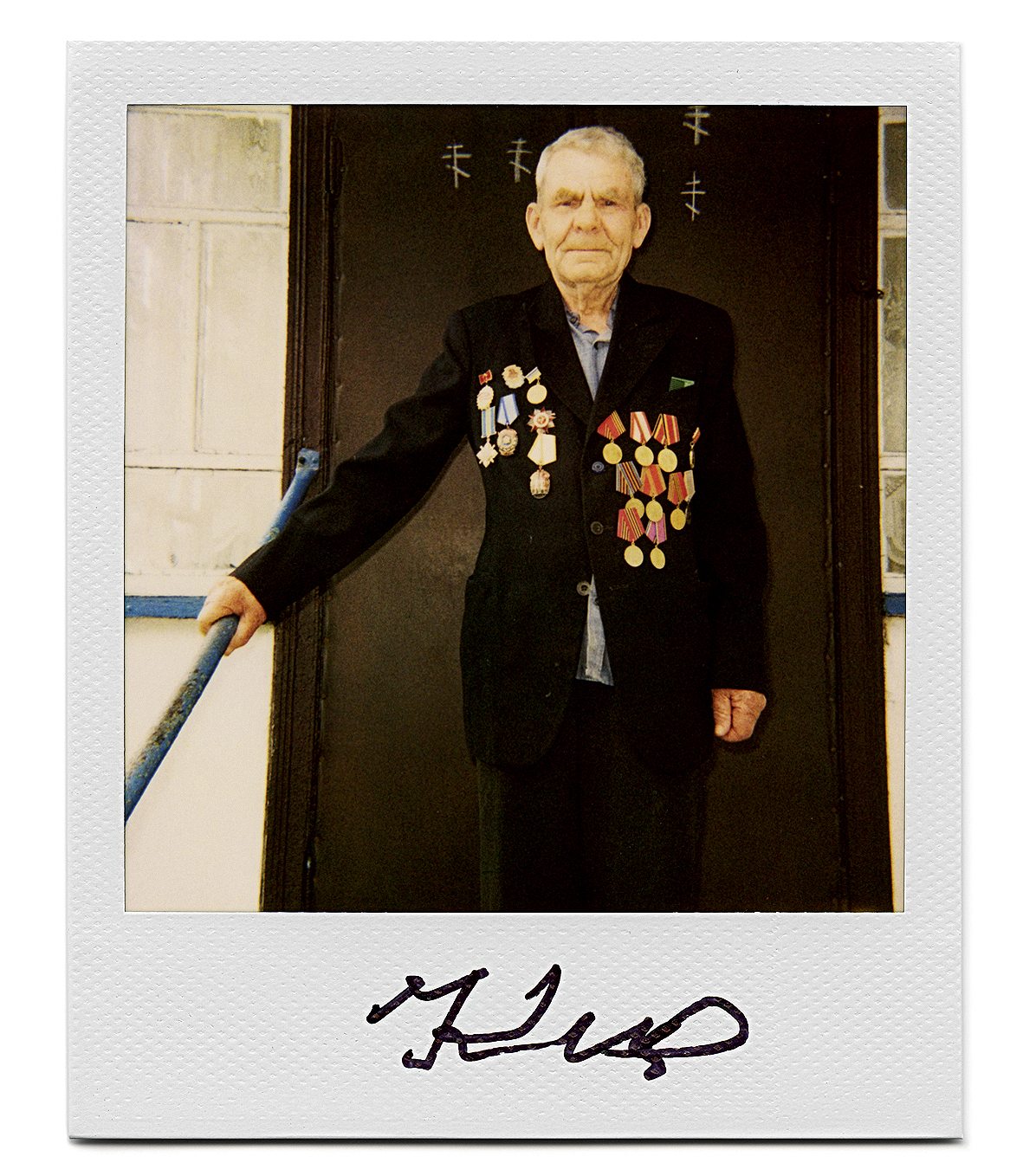

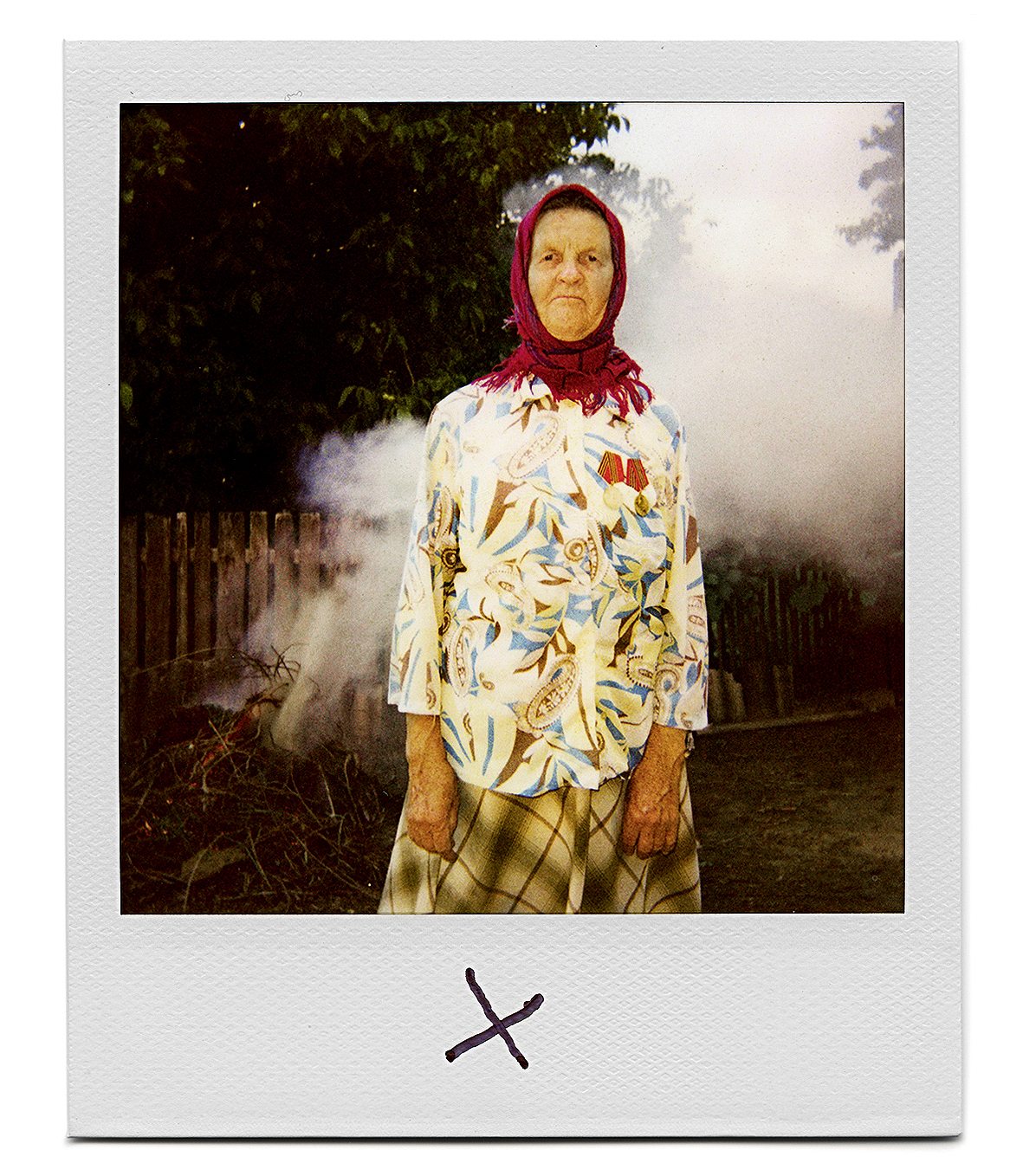

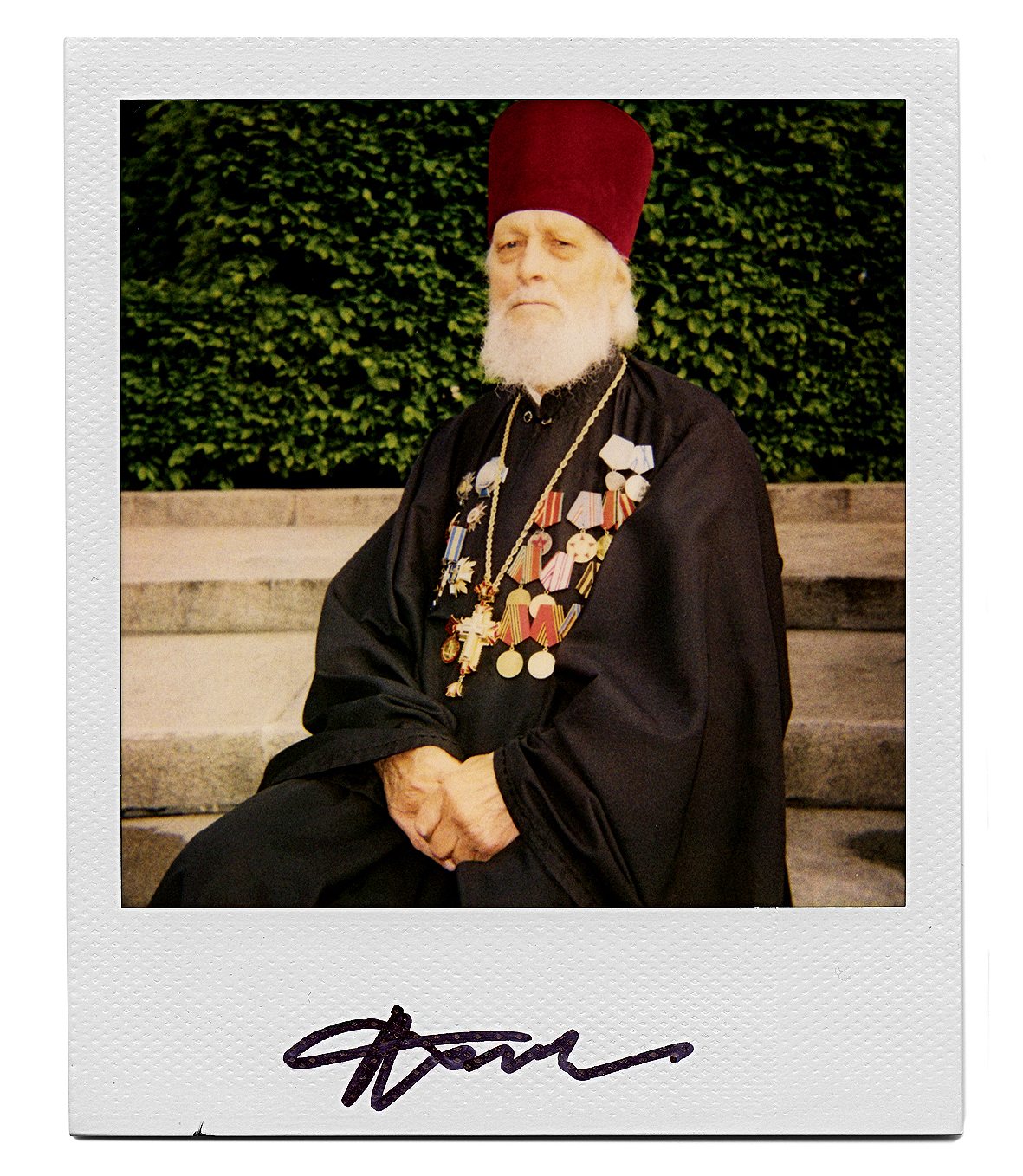

R&K: There is something interesting about the use of Polaroid, instant film, and the themes you are exploring: remembrance, aging, memory. Why did you decide to use that kind of film?

Bondar: The main idea of the project was to create a trace, a story, a memorial to all of these veterans. But at the same time, I wanted to express this feeling of time and aging. An old Polaroid camera and instant film became the perfect tool for that. And I love these small, square images so much because they are so intimate. It is impossible for ten or twenty people to look at one Polaroid picture together. Only one person can do it at a time. And when you look at the person on the photo, you can feel the connection and dialogue between you and them. You can feel the same feelings that I felt when I met all these people.

R&K: The signature below also says so much about the person being photographed.

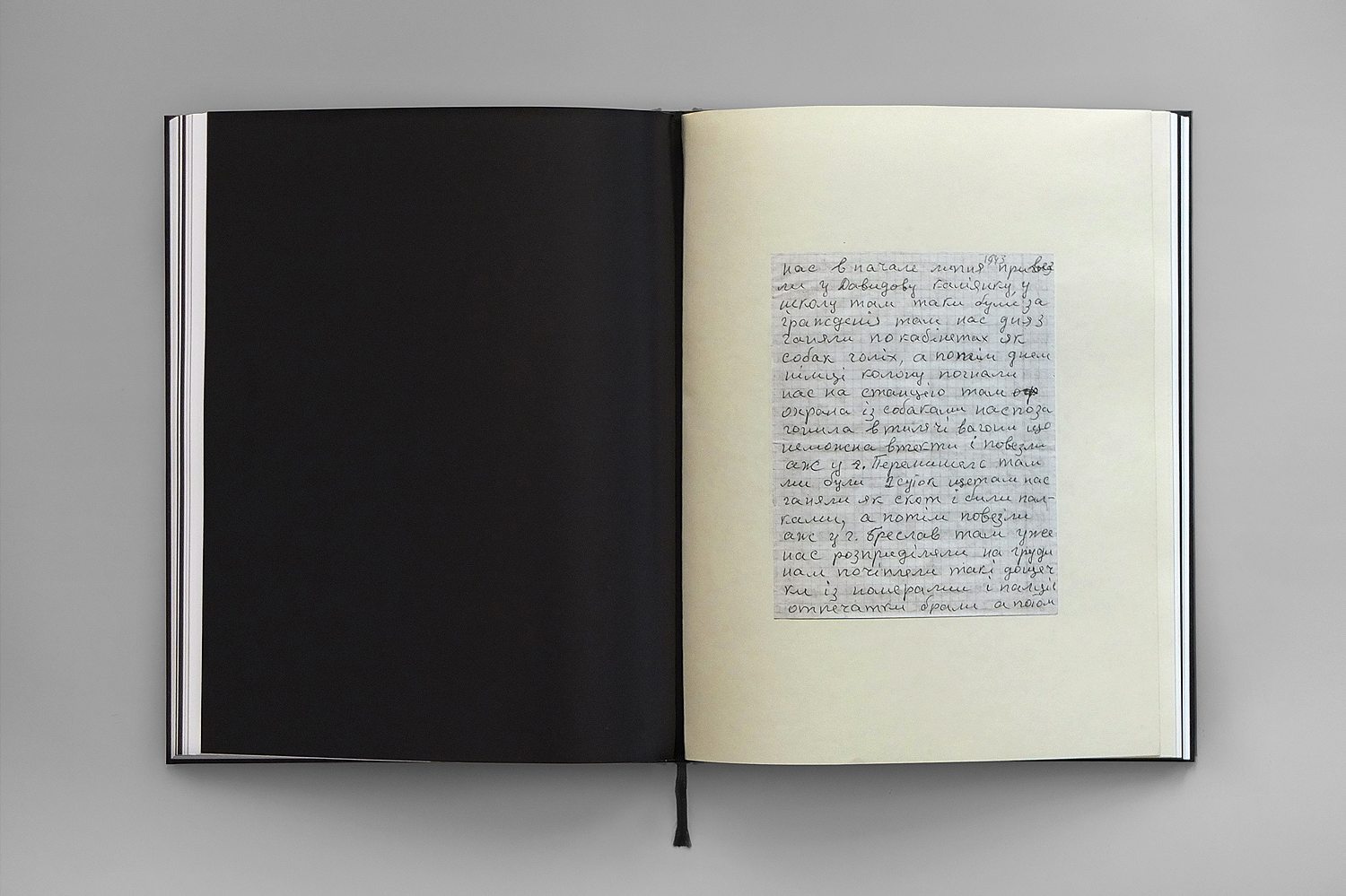

Bondar: We leave many traces behind after our lives are over. These traces are usually our letters, our diaries, our photographs. When I started this project, I found a letter from my paternal grandmother, who was also a veteran. She described her life during World War II in great detail. I also found a lot of photographs in her archive with signatures on the back. All of these things made me think of asking for signatures and adding one more layer to the project. I think our signatures can say a lot of things about us.

R&K: How did your family react to you doing this project? Has your relationship with your grandmother changed?

Bondar: My family is an ordinary Soviet family. My father is an engineer and my mother is a dentist. When I started photography, they were quite skeptical about it. For a long period of time, my parents asked me to find a normal job. Now, they feel that this is a huge piece of our history and that we should keep it and remember it, especially today, when Ukrainian history is being rewritten by politicians. I definitely grew closer to my grandmother during these past five years. Many things have changed during this time in my personal life. Veterans that I photographed have now died, and I have been thinking a lot more about people like them. When I look at their pictures and signatures, I feel that I am on the right path.

R&K: Can you tell us about one character that had a strong impact on you?

Bondar: All of them had a huge impact on me. But I remember one veteran that I met in my hometown of Krivoy Rog in Ukraine. When he looked at his Polaroid picture as it developed, he said: “That is so great. It is my second picture after the War.” That was very striking. Another story was with a veteran from Lugansk, where the war is going on today. I met him at the train station in Kiev and helped carry his bags. He told me about being heavily wounded and spending two days under the ground, unconscious, and how his first love, Galina, had saved him. There are so many others.

R&K: What effect did the war in Ukraine have on you and on the project?

Bondar: I have not met anyone who isn’t affected by war in his home country. No matter how far he is. The same happened with me. I was at Maidan and went to Donbass several times. When you hear the horrible stories from both sides of the conflict, it is impossible to say who is right and who is wrong. A lot of veterans I spoke to were really confused by the current situation. They said that it was the biggest tragedy of the post-World War II era. One veteran said that Russians and Ukrainians fought against the Germans in the same army, in the same regiments, and in the same trenches, but that today they kill each other. It’s a disaster.

R&K: What is there to learn from people who have lived through war?

Bondar: As the great journalist and writer Marina Akhmedova wrote in her introduction text to “Signatures of War:” “People born under peaceful skies with no knowledge of war [don’t] do all they can to avoid it.” I think this is the most important lesson that we can learn from the veterans. We should remember the horrors of war and our history. Only then can we take a step forward towards peace.

R&K: You photographed the heart of the action at Maidan and throughout your career. What is different about photographing people who live on the edges of society?

Bondar: Making such a big and important project like “Signatures of War” made me slow down. Old people are very slow. They are not in a hurry anymore. I just listened to their amazing stories and enjoyed their great company. Sometimes it’s so important to stop and think about the story, instead of running towards the news. I am really grateful to all the veterans for their trust and for letting me collate their memories. It is so important to me, to my family, to my country and to all of us.

You can purchase “Signatures of War” here.