Inside the complicated communities surrounding Okinawa’s controversial U.S. military facilities.

Most headlines about the U.S. military bases in Okinawa tell stories of local opposition. The bases take up nearly 19 percent of the main island and bring with them roughly 25,000 U.S. service members. For decades, they have been protested as sources of crime, symbols of discrimination and oppression from mainland Japan, and evidence of the United States’ global “empire of bases.”

Most recently, the prefecture’s governor, Takeshi Onaga, has proven to be a staunch and outspoken opponent of the bases, standing up to the national government like few local leaders have. This week, Onaga is taking his protest to Washington, D.C., after April’s summit between Prime Minister Shinzō Abe and President Barack Obama resulted in renewed commitment between the two countries to build yet another base.

I lived in Okinawa—a chain of subtropical islands removed geographically, culturally, and historically from the rest of the country—from 2008 to 2009, while researching a book on the effects of the U.S. military presence there. I came prepared to hear grievances and opposition from locals—but was surprised to find that many people I met took a more pragmatic view.

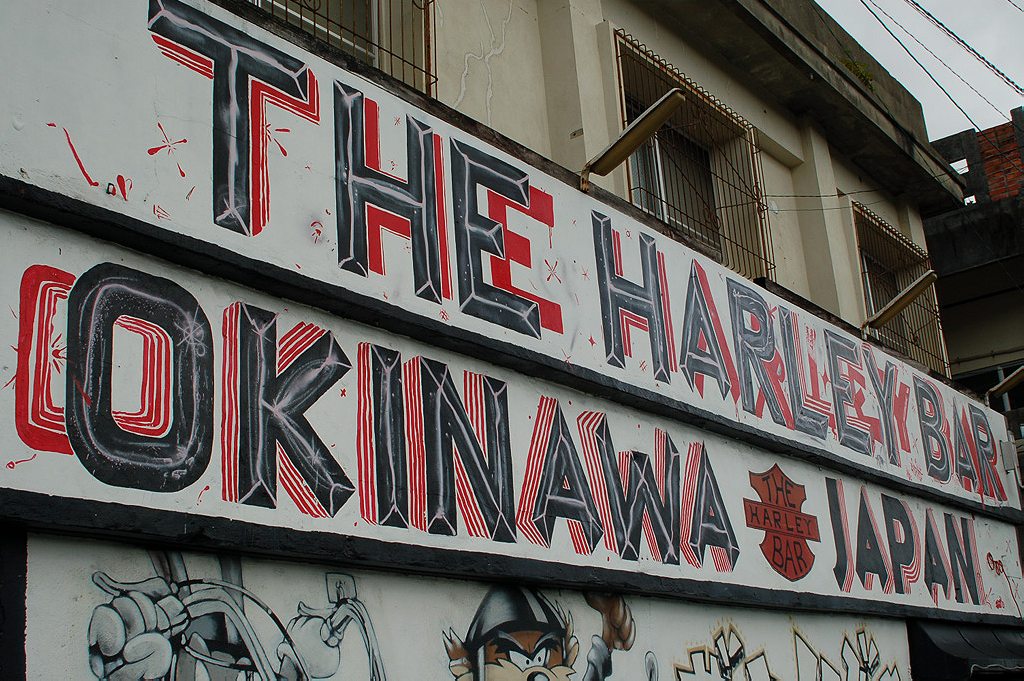

This was a dimension to the U.S. military presence I hadn’t expected to find. In the borderlands around the bases, Okinawans, Americans, and Japanese have forged unique, multicultural communities in which many people thrive. The population and culture reflect the fact that Americans have mixed and interacted with locals for decades. The server at the ramen shop could pass for a local in Brazil, Hawaii, or East Harlem. The grocery store sells Kraft macaroni and cheese. A local favorite, taco rice, is made from layers of Mexican-seasoned ground beef, cheddar cheese, and iceberg lettuce atop a bed of Japanese white rice. Groups of women identify themselves based on their desire to date American men, altering their appearances and speech to blend in with the soldiers. A neighbor, a cousin, a friend, a lover—everyone seems to know someone with a connection to the U.S.

On a Saturday night in September 2009, Yasushi Tamaki told me that Okinawans needed to negotiate the bases, not get rid of them. “So many people make a living off them,” he said. Tamaki had worked as a bartender at Hard Reef Bar in Chatan, Okinawa, for three years when I met him.

Affable and tan, he was in his mid-thirties, dressed in a Denver Nuggets jersey and a newsboy cap. An Okinawa native from the capital city, Naha, he said he had a “shisa” face—the round eyes and broad nose of the traditional lion dogs that guard homes. “I have an Okinawan face,” he told me. “Different from faces on the mainland.”

That night, Hard Reef was filling with American servicemen and local women. American hip-hop and pop music blared. I spotted a few Japanese surfers here and there. A local had told me that the bar, which had a thatched ceiling and mounted televisions playing surfing films, had started as a surfer bar 20 years ago. But the surfers didn’t have money; they bought one drink and went home. So Hard Reef worked to attract more lucrative clientele.

“This place runs off military people,” Tamaki said.

The area around Hard Reef is dominated by U.S. military bases. Up the road sprawls Kadena Air Base, which eats up over 11,000 acres of this part of Okinawa, the main island’s skinny waist. Just south is Camp Lester, and then comes Camp Foster. Farther down Route 58 is the notorious Marine Corps Air Station Futenma. Jammed in the middle of Ginowan City, abutting schools and homes and businesses, Futenma was allegedly called “the world’s most dangerous base” by former U.S. Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld. Efforts to close it have been stalled for years over disagreement about how and where to relocate it.

“People may have different opinions about the bases, but making a living is the most important thing,” Tamaki said. He mentioned the number of Okinawans who worked on base, rented apartments to Americans at inflated rates, or leased land (really without choice, having been evicted and forced, postwar) to the U.S. military.

I sipped my beer and watched footage of a surfer cruising down a brown river. I knew this argument for the bases—that they’re needed for Okinawa’s economy—didn’t hold much weight. On Okinawa, the bases can seem omnipresent, but base-related income makes up a smaller fraction of residents’ total income than commonly thought—only about five percent.

Increasingly, locals argue that the return of land and resources taken by the military, including key urban areas like Futenma, would help the prefecture more. But to people who work at businesses like Hard Reef, the bases can feel like everything.

Tamaki pointed to a Marine drinking by the pool table: Max, a friend of his. Tamaki had become friends with many of the American servicemen who came to the bar—guys in their twenties who called him grandpa (he called them babies). Sometimes, he went to their places for barbeques or to play video games. When they hung out, they slowed down their speech for him so that he could understand their English.

These relationships influenced Tamaki’s opinion of the bases as much as any economic argument. The community that has developed around the bases had come to feel like home. In Naha, where the U.S. military presence isn’t as prominent, Tamaki had grown up without much exposure to Americans. Like many people there, he’d held a more anti-base view. Then he moved north to Chatan, into a mix of Americans, Okinawans, and Japanese. Living alongside the bases, spending shift after shift with his American customers, had changed how he felt. Gradually, he got so used to the diversity when he left the area and was surrounded by only Okinawans, he felt unsettled.

Another bartender offered me a bowl of edamame. He was a quarter American, he told me. When he was growing up, there was a picture of a white guy around his house: his American grandfather, who was from Cleveland.

My friend with me at the bar was also mixed-race. Bilingual, she grew up on the island with her Okinawan mother and American father. Her parents had divorced when she was an adolescent, but each still lived on the island and had remarried. She was close to her father, often meeting him for lunch on Camp Foster, where they both worked. As a family, they spent their lives on and off base, in English and Japanese, among Americans and Okinawans.

Her father, Tommie “Mac” McGowan, relied on the bases even more than Tamaki. “Without the bases, I ain’t got a job,” he told me. “Without the bases, I got to leave.”

McGowan was a retired serviceman who’d first arrived in Okinawa in 1977, a security police officer in the Air Force. He’d be able to stay in the country legally if the bases were removed because he was married to a Japanese citizen and had a spouse visa. But he wouldn’t be able to earn a living, not easily—his Japanese language skills weren’t good enough.

The bases enabled McGowan to live in Okinawa, but they weren’t why he stayed. To him, Okinawa felt like home in a way that Mississippi, where he’d grown up, never had. An African American, he hated the racial tensions of the South. Okinawa felt more accepting. “I feel comfortable in Japan,” he said. “In the States, you got to look over your shoulder all the time. Here, I don’t worry about my wife or daughter being safe when they go out. It’s a warm feeling.”

When freed, many found their homes gone

Today’s headlines about Okinawa aren’t about warm feelings. Governor Onaga remains deadlocked with the Abe administration over construction of a new military facility in northern Okinawa, in the Henoko district. Not densely populated like Ginowan City, the location is billed as a safe replacement for Futenma, but opponents like Onaga say those Marines should be moved off the island completely.

For many, the present situation is inseparable from Okinawa’s history. This spring marks the 70th anniversary of the Battle of Okinawa, the “typhoon of steel” that killed more than one-fourth of the prefecture’s population. In the battle’s aftermath, the American victors confined Okinawan survivors to internment camps. When freed, many found their homes gone—leveled to make way for gleaming American military facilities.

During its 27-year rule of Okinawa postwar, the occupying American administration took more land for bases by “bulldozer and bayonet.” Thousands of displaced people struggled to rebuild in new and unfamiliar spaces, resigned to finding low-paying service jobs on and around the bases. Many couldn’t afford basic conveniences like electricity and running water. Meanwhile, Americans resided in compounds of wealth.

Today, the prefecture remains the poorest in Japan, and the Japanese and American governments’ insistence on this new base despite local opposition recalls the seizure of land postwar. The push for the Henoko facility can be viewed as another injustice in a long line of them. These include the forced annexation and assimilation of Okinawa, once an independent kingdom; civilian deaths at the hands of Japanese soldiers during the war; U.S. occupation that lasted 20 years longer than on the mainland; and, of course, all those bases.

Onaga is determined to make clear to U.S. officials that Okinawans have said no to this base through local democratic processes, and I hope that he is heard. The time for Japan and the U.S. to uphold the democratic rights of Okinawa’s people is far overdue. At the same time, I know that for many of those who have made their homes around the bases, the question of the U.S. military presence can feel complicated.

At Hard Reef, the crowd grew louder as the hours passed. A woman named Rina, in her early forties with long, dark hair and big eyes, told me she’d been coming to the bar since its surfer days. Her mother was Okinawan and her father was a former U.S. serviceman. Rina used to be a surfer herself, and the owner of the bar had taken her under his wing. Rina was defensive of Hard Reef, insisting people went there for the sense of community, not just for drunken hookups.

Later, I watched a guy lift a woman onto a table. She wrapped her legs around his waist and they made out like they were headed to war in the morning. The characterization of Hard Reef as a hookup spot didn’t seem undeserved. Still, I thought I knew what Rina meant.