Pasteurized pulque can reach new audiences, but is it sill pulque?

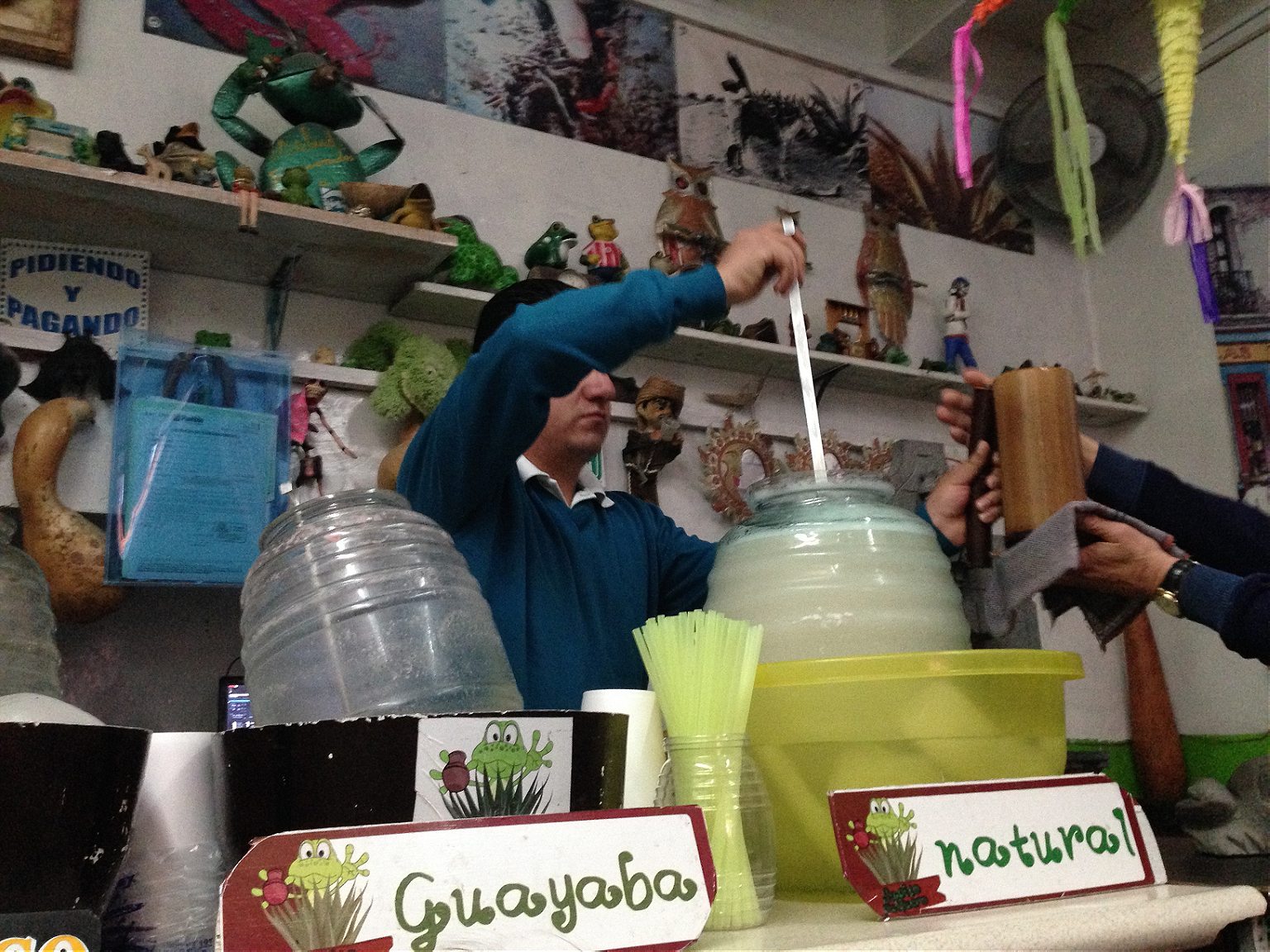

At around 7 pm on Friday, it’s still happy hour at Pulqueria, a speakeasy-style Mexican bar in Manhattan’s Chinatown. Pulque Clasico, described on the cocktail list as “natural fermented agave juice,” goes for $6 a glass. In the traditional Mexican pulquerias the bar is named after, pulque is usually ladled out, fresh and thick, from clay pots. Mishi, the bartender in Manhattan’s Pulqueria, pours it from an unmarked squeezy bottle, the kind you use for simple syrup. The guy on the barstool next to me is on his second round and wants to know more about it. “It’s an ancient drink, with an alcohol content similar to beer, and a flavor comparable to unfiltered sake,” I hear the bartender tell him. No, he says, it’s not from a bottle.

Pulque that’s sold outside of Mexico has to be pasteurized, and it comes in a can. Heather Weinthaler—an importer of Pulque Hacienda 1881, a brand of canned pulque—says that although the bar community is curious about the beverage, there’s reticence about using the canned stuff, which is widely considered inferior. She supplies a pulqueria in Chicago whose owner prefers that the cases be delivered outside of business hours. “He’d rather not tell his customers he gets his pulque from a can. When people ask he just says it’s from Mexico. Maybe they assume it comes in a barrel or something,” she says.

In Mexico, pulque is traditionally consumed fresh. Fresh pulque has a slight pong that’s a little like fruit left out too long, and a viscosity that’s hard to get used to – midway between spit and semen. But it does have a part-sweet, part-tart effervescent complexity that’s all its own. Canned pulque tastes, well, like juice. Pasteurization stops the drink’s fermentation process, allowing it to reach new audiences, but also changes its character. For purists, that makes it harder to like.

A few months ago, in Puebla, Mexico, I was handed a bubbling Coke bottle’s worth of the fresh stuff, funneled straight out of a barrel. This was day-old pulque made by Josué Aguilar Roldán, who has worked as a tlachiquero, or pulque producer, for the past 25 years.

Roldán, who lives in La Preciosita, a village near Puebla, tends to around 60 maguey plants in a small sloping field, enough to net him just under 200 gallons of pulque a week. He has to wait nearly a decade for the plants to mature, and when they are ready, he collects the sap—or aguamiel—with an acocote, a fiberglass pipe, twice a day.

His tinacal, the place where he ferments the aguamiel to make pulque, is a tiny mud-brick shed in his backyard. There, aguamiel at different stages of fermentation rests in big plastic barrels. The fermentation process occurring in Roldán’s shed makes the syrupy-clear “honey water” frothy and milky. Pulque turns yeasty and sour if it isn’t consumed within one to two days as the fermentation continues. That’s why the farthest Roldán has sold his pulque are neighboring towns San Martin and Coltzingo.

Tess Rose Lampert, a New York-based agave specialist, believes that the premise of packaged, exported pulque is a shaky one. Lampert is a member of the Tequila Interchange Project, a collective that promotes artisanal agave distillates. “Pulque in a can is just not pulque. Maybe it’s viable in cocktails, because then it’s a background note. But pulque is a living beverage, and pasteurization just kills it,” she says.

Alex Valencia, the bar manager at La Contenta on the Lower East Side, does give pulque a spot on his alt-agave menu, running through a can a day. Valencia, who grew up in Guadalajara, says he knows “the flavor of canned pulque is not real” but it’s his only option. “It’s my job as a bartender to work with what I have. It’s not perfect, but it’s still a way for people to try something they probably haven’t tried before,” he says. Besides, historically, pulque has had the odds stacked against it, so he wants to do what he can to promote it.

For centuries, pulque posed a moral, spiritual, and political threat to Spanish rulers, says Daniel Nemser, a University of Michigan professor who specializes in colonial Latin American history. The drink was considered sacred by the Aztecs, who drank pulque during rituals, on festivals, and for medicinal purposes (Roldán describes it as “Mexican Viagra”). However, according to Nemser, colonial powers took a different view. “Pulque was seen as a corrupting influence on indigenous populations. The Spanish thought it was disgusting, and they wanted to get rid of it,” he says.

Its decline continued in independent Mexico, says food historian Rachel Laudan. “German brewers came into Mexico with big modern factories in the late 19th century. There was this argument, a calculated campaign to discredit pulque, really, saying that beer was a scientifically produced, European drink, while pulque was backward and unhygienic, that excrement was used to ferment it,” she says.

These centuries of targeted prejudice were not without effect. Pulquerias, once fixtures on most street corners in big cities, began to drift out of business. Valencia recalls that as the pulque market dried up while he was in school, sweet aguamiel was sold as a cheaper alternative to soda instead of being fermented.

As pulque hit the lows of Valencia’s childhood, Rodolfo Del Razo, a tlachiquero from Tlaxcala, was working to refine the process of pasteurizing pulque so that it could be introduced to export markets. The technique took Del Razo around 30 years to perfect. Basically, fresh pulque is first heat-treated in a pasteurization machine and then poured into cans. The cans are sealed, placed into hot water to reduce the risk of thermal shock, and then quality checked before being packed into pallets. It’s a tricky process: if fermentation is not stopped completely, the cans bulge and then explode; too much heat, however, will affect the taste. But in 1994, he finally succeeded.

In the last decade or so, pulque’s fortunes have begun to change. “In 2005, when I was in Mexico City, pulquerias were populated by young Mexican students dressed in black and listening to Bob Marley,” says Nemser. “My sense is that pulque had become a symbol of subculture, a way to incorporate the indigenous past into their identity.” By 2013, he says, there were multi-level pulque bars located in upper-class neighborhoods. It looked like pulquerias, in some pockets at least, had become trendy.

But this revival appears to be confined to Mexico, despite Del Razo’s efforts. In April this year, the New York Times published a piece about the next wave of agave spirits— sotol, bacanora, and raicilla—edging their way into cocktail lists. But pulque, their pre-Columbian predecessor, seems to have been passed over. Weinthaler admits that tequila and mezcal still make up the bulk of her portfolio. “If someone were to say I’m going to get a license just to sell pulque, I would say good luck with that,” she says.

Mixologist Junior Merino, who promoted traditional beverages for the Mexican government until President Nieto took office in 2012, believes that pulque could reach more consumers if it were marketed to even a fraction of the extent that cerveza, tequila, and mezcal have been, even with the limitations of pasteurization. “With more showcases and events, people will get excited about it. It could be an amazing product, but if no one knows about it, who cares?” He adds that the beverage needs a stronger distribution network as well: “You used to be able to find it, and now it’s harder,” says Merino.

As Merino points out, the supply hasn’t always been consistent or widespread. Dan Benavidez, a former consultant with Boulder Imports in Colorado, was the first to bring pulque to the US in the early 2000s. He imported Nectar Del Razo and the now-defunct Pulque la Lucha labels to 22 states in the country. But around 2008, the producers didn’t think the market was growing fast enough, he says, and there was a hiatus in exports. Weinthaler, who is licensed for the Illinois market, says that about two years ago, when the Del Razos were in the process of selling their Pulque Hacienda 1881 brand, she didn’t have any pulque to sell. “It took some time for the new owners to be sure they wanted to continue doing business in the US,” she says.

Currently, pulque is only sold in four states: New York, California, Illinois, and Washington. And even there, it’s not likely you’ll find six-packs of pulque on your local supermarket shelves. Chances are better in small bodegas—say, Mexico 2000 in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, or El Popo Mini Market in Jackson Heights, Queens—but you have to know what you’re looking for and hope they have a couple of cans in stock. And there are only two brands widely available within this niche market: Nectar Del Razo, the kind Valencia uses, and Pulque Hacienda 1881. Both offer a natural flavor, as well as variants like strawberry and coco-piña, and retail for around $2.50 a can.

Back in Puebla, the price for pulque is between 5-8 pesos per liter (around 30 cents), making it difficult for small-scale independent producers like Roldán to stay in production. Of his four brothers, he is the only one making pulque. His brother-in-law has chosen to grow corn and fava beans. Roldán has been collecting aguamiel since he was 13; he says he does it because his father used to do it. But his son, still young, does not seem interested. “He would like to study and go to college.”

The tlachiquero didn’t have much to say about the practice of commercializing pulque for export—his pulque doesn’t travel farther than the next town, and growing international demand would just make it more likely that the acocote will soon shift from the hands of small producers to commercial stakeholders.

Even as small-scale pulque producers in Mexico face an uncertain future, Lampert from the Tequila Interchange Project hopes that some enterprising farmer considers producing pulque within the US. “I think we’ll see that kind of agave grown in Texas or Arizona within the next decade,” she says.

But until then, there is one way to try unpasteurized pulque in New York. La Contenta’s Valencia has a “friend in Tlaxcala” who brings over three liters or so every few weeks. The bartender can’t sell it, but he can offer his customers samples for free, poured out sparingly into shot glasses. “I put it in the freezer and use it little by little. This way, at least people will get to know the real flavor,” he says. On the night I visited, I was lucky enough to try the last of his current batch. It tasted nothing like juice.