A conflict between the government and indigenous people threatens one of Brazil’s most unique national parks.

LAGOA DA CONFUSÃO, Brazil—

It was noon, and we were driving west as drab fields of parched soybean and scrub rushed past. Our goal was to find a local with a skiff who could take us across a river and into a national park that does or does not exist, depending on whom you ask.

There was a metallic click as my companion, Raoni Japiassu Merisse, the very real boss of this paper park, slid the ammunition cartridge into his black semiautomatic pistol engraved with the initials of his employer, the Chico Mendes Institute for Biodiversity Conservation. Japiassu had never fired a single shot outside of his training, but he was prepared to. “Our leaders believe we are at war with the indigenous,” he said with a mixture of duty and resignation.

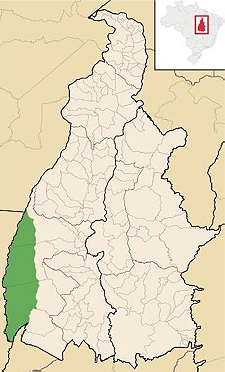

Just 30 years old, Japiassu was the man caught in the middle of what he called “an impossible situation.” On federal maps, Araguaia National Park still encompasses the northern third of Bananal Island, a 200-mile long river island in north central Brazil that is shaped like a crude arrowhead pointing north. The place was once considered Brazil’s answer to Yellowstone, but 13 years ago, the Javaé and Karajá tribes who live on the island took one of Japiassu’s predecessors hostage, commandeered boats and vehicles, and set fire to the park headquarters.

They were angry about attempts to rein in illegal fishing and cattle ranching, activities that brought outsiders—and cash—to the impoverished island people. After a long struggle, federal lawmakers demarcated new indigenous territories that have complete overlap with the park’s boundaries, creating a legal conundrum. Japiassu’s bosses back in the capital of Brasília demand that he enforce Brazil’s conservation laws inside an indigenous territory where he no longer has unambiguous jurisdiction.

Every year, the forest becomes a veritable inferno as it is set ablaze to facilitate dragging nets along lake bottoms and to make room for illegal cattle pastures. Over the last 10 years, satellites have recorded 3,611 fires inside the park, according to the National Institute for Space Research.

If Japiassu ever has to unholster his weapon, the subsequent outrage could topple the government’s tenuous hold on the island. When he began working in 2008, there were 12 people working in his office. Now, there were just three. The park, at that moment, had a half-dozen boats it had seized from illegal fisherman, but it didn’t have a single working motor. “The indigenous people won’t leave this area,” he said, “but it’s possible that we will leave one day.”

Japiassu has wild, curly black hair and a scraggly black beard covering the chin and jawline of his angular face. He reminds me of the park’s mascot, the jabiru, a lanky stork common along the Araguaia River. He wears rectangular glasses perched on his beak of a nose, and he speaks English cautiously, enunciating each syllable with a deep, emphatic voice. When I visited him in February, his wife was two weeks away from giving birth to their first child.

“Does it make your wife nervous?” I asked, gesturing at the pistol.

“I can only tell her the main things,” he said. “I try not to alarm her.”

It took all day and part of the next to reach the river’s edge because of one delay after another. Standing on the high bank at last, I got my first glimpse of the vast green canopy stretching across Bananal Island. It is the largest river island in the world and the place where two of Brazil’s most diverse ecosystems—the Amazon and the Cerrado savanna—collide with all the biological fireworks that entails. Low-lying parts of the island are eerie-looking flooded forests with freshwater sponges clinging to stilted roots. Areas of high ground, where the 34 indigenous villages of the Javaé and Karajá are scattered, look like classic Cerrado: a blend of dry forest, scrub, and grassland.

During the dry season from May to September, the game trails are thick with the three-toed tracks of tapir and the paws and claws of jaguars and giant anteaters. As the water level drops, temporary lakes, known as igapós, become cleaved from the river course, trapping hundreds of bizarre fish species, including the 400-pound pirarucu, a silvery monster with teeth on its tongue. Deep in the Mata do Mamão, a dense, nearly inaccessible forest on the center of the island, rumors persist about an uncontacted tribe of Ava-Canoeiro Indians.

Japiassu is trying to rebuild the park’s relationship with the indigenous, one village at a time. He had established a relatively good rapport with Walter, the chief of Txukode who was supportive of the park’s enforcement efforts—so long as they benefited his people. Walter is a mellow, friendly man with graying eyebrows and a constellation of pockmarks on his cheeks. After discussing the conflict with Walter at his second home in Lagoa da Confusão, he had agreed to give us a tour of his tribal land in exchange for 50 gallons of gas.

After we pulled out from the cove where Walter hid his skiff, we headed south along the main channel of the river with Bananal Island on our right. The water was unusually low for this time of year, and the sandy beaches were packed with water birds along with the occasional black caiman, a once-endangered species whose numbers have recently risen. In the overhanging scrub, I spotted what looked like a chicken with a mohawk. This was a hoatzin, famously called the stinkbird because its herbivorous diet endows its droppings with a barnyard stench.

According to the Javaé people, there was a time when the sun was as black as swamp water. They lived in a magical realm beneath the bogs and rivers of Bananal Island. In this subterranean Eden, everyone was healthy, no one quarreled, and no one ever died. If you thought about eating fish for dinner, a fish would materialize before your eyes.

But this region, called Berahatxi, was far from perfect. The world was thick in an ankle-deep layer of mud. The water there was murky and foul-tasting. The fish always seemed undercooked. No one had ever experienced the pleasure of sex. One by one, these people explored tunnels that would take them out of the depths, and they began to encounter other people who had already emerged.

The Earth’s surface, the Brazilian anthropologist Patricia de Mendonça Rodrigues has recounted, “would prove itself to be both fascinating, owing to the novelties that were to be found, and terrifying, owing to the prices they would have to pay for being there.”

A Fitzcarraldo-esque dream to create a Brazilian identity

The idea to establish a national park on Bananal Island came from a black abolitionist and military engineer in the state of Bahia. In 1876, André Rebouças was inspired by the establishment of Yellowstone and suggested that Bananal Island could become one of Brazil’s first parks. Almost 90 years later, on Dec. 31, 1959, President Juscelino Kubitschek declared the entire island Araguaia National Park.

Kubitschek had a Fitzcarraldo-esque dream to colonize the nation’s interior and create a Brazilian identity. As part of Operation Bananal, he brought in modernist architect Oscar Niemeyer to build a stilted hotel and resort, the Hotel JK, overlooking a crocodile and piraña-infested beach near an Indian village on the Araguaia River.

“Here—where they were alone, abandoned in the jungle—on the 27th day of July 1960, began the integration of the Bananal Island community by the will of President Juscelino Kubitschek, helped by God and men for the love of Brazil,” read a plaque at the president’s island residence, called Alvoradinha.

The indigenous people were far less exuberant about this arrangement. Brazilian settlers invaded indigenous land in greater numbers, fishing with nets and dynamite and stocking the island with as many as 200,000 head of cattle. When they actually paid to lease the land, it was often for far less than the market value. Villages were robbed of the hardwood trees. Violence was common. “An Indian by the name of Luiz was beaten up, by four young men, so that they could have sexual intercourse with his Indian wife,” a government official wrote in a report from 1964. “Sir, the Javaés have been suffering for years, without those who commit the crimes being punished.”

The history of the park since Kubitschek’s time goes like this: In 1971, the Brazilian government gave three-quarters of the island park over to an indigenous reserve. In 2002, the Javaé and Karajá demanded more. They invaded the park headquarters and razed a fisheries inspection station.

By 2010, the Brazilian government had conceded to their demands and established two new indigenous territories in the north that would have complete overlap with the national park. For conservationists, it was the beginning of the end. “Bananal Island has now fallen into the maw of the Indian,” wrote Marcos Sá Correa, the editor of the Brazilian environmental news site O Eco.

Japiassu’s first job with the park involved trying to put an end to illegal fishing with a groundbreaking fisheries agreement with the indigenous people. Each resident would be allowed to fish for 100 kilograms each month and could sell what he or she pleased. Outsiders, however, were forbidden from fishing under any circumstances.

Japiassu felt good about his work and was fond of the indigenous people. He was born in Goiana, a pleasant city in the center of the country, but raised in Palmas, the steamy capital of Tocantins state. His mother named him after Raoni Metuktire, the Kayapo chief who, in 1989, made a global tour with Sting in order campaign for the establishment of a united indigenous territory along the Xingu River. “I always loved the Cerrado,” he says. “I wanted to fight deforestation.”

The head of the park at the time told Japiassu that his job was always to build relationships. “I am the bad guy, and you are the good guy,” he told him. But in early 2012, the park head announced that he was departing and that Japiassu would have to assume his mantle. In other words, he would have to become the bad guy.

During a crackdown on illegal fishing that implicated the owner of a restaurant in the city of Porto Nacional, Japiassu confronted the chief of Boto Velho village who had given the fishermen access to waters inside the national park. He showed him photographic evidence of the crime and said that no punishment would befall the indigenous people—only the fishermen. He demanded that the chief let his men enter Boto Velho and seize their boats. The chief refused. “I am not afraid neither to die nor to kill,” the chief told him. “If something happens, you will be the person responsible.”

Japiassu resolved to isolate the rogue chief. He announced that he would no longer send his firefighters into the disputed territory, arguing that the threats had made him concerned for their safety. When a fire broke out in May 2012, Japiassu monitored it by satellite, watching it grow pixel by pixel. By the second week, it was the largest forest fire in the country and appeared on the nightly news program Fantástico.

Japiassu’s superiors in Brasília were caught off-guard by the negative publicity. They ordered him to take action, and he found himself begging the chief for a guarantee of safe passage. “It was humiliating, not just for me but for the Brazilian government,” Japiassu told me. “It destroyed all of our work.”

Out on the river, Walter waved to one of his relatives, bobbing up and down in the water, trying to untangle a net beneath his motorized canoe. When we came for a closer look, we saw five hefty freshwater turtles wriggling on their backs.

Our boat made a wide arching turn across the flat water and followed a tributary into the island’s interior. Suddenly, a pinkish dolphin breached the surface and exhaled from its blowhole. Walter cut the engine, and we were surrounded by about a half-dozen of these dolphins, popping up, snorting, and then vanishing again in the black water.

Walter chuckled at their antics and said his people revered the curious animals. So do scientists: Last year, they recognized the Araguaia river dolphin as a new species, isolated by rapids from the other two dolphins living in the Amazon.

When they arrived at Walter’s village, a dusty smattering of huts on the edge of the park, we goofed off with a bow and arrow, and the men performed a traditional song for us. As I wandered around under the searing sun, I met a 22-year-old man named Araruwe who was resting on a hammock made from a tattered fishing net. He had recently migrated here from Cananoa, a village in the south.

He said that there were too many people using the indigenous reserve and the hunting and fishing had deteriorated. Inside the national park, he said, you could have all the fish you desired.

Knowing the sad history of this place, I sympathized with the indigenous people. At the same time, it was hard to understand how a population of 4,300 needed the island’s entire 8,000-square-mile area to survive. That’s 1,200 acres for every man, woman, and child. How is it possible that they cannot use their resources more efficiently?

Japiassu knew his own days were numbered, as the indigenous kept moving north. Illegal fishing was still a problem, and cattle numbers on the island were rising again. Walter had said he would cooperate on efforts to keep cattle out of the park, but Japiassu knew that would only work if the tribes had an alternative source of income. He felt like he was a man alone, fighting for something he wasn’t sure he believed in anymore. He would leave as soon as he found someone to replace him. “I don’t want to take part in this lie,” he told me. “I am starting to think, maybe, it would be better to extinguish the national park.”

At the end of our visit, sweat was dripping down Japiassu‘s brow, and we were both thirsty. Walter pulled a pitcher of water out of the refrigerator at the concrete block school and poured it into a glass for Japiassu. He held it up to his eyes. It was the color of weak tea. He had no choice. He took a sip and said it tasted like dirt.

Reporting in Brazil was supported by the Mongabay Special Reporting Initiative.