Dead Wallabies and Illegal Stills

Dead Wallabies and Illegal Stills

Rye in Tasmania

It was in a foggy parking lot in central Tasmania, at a lone telephone booth glowing by the roadside, that I first bent down and found all the blood and fur stuck to my bumper. Actually, it was stuck in the bumper. I went into my room at a little lakeside fishing lodge, grabbed a flashlight, and splashed a handkerchief with some lukewarm water.

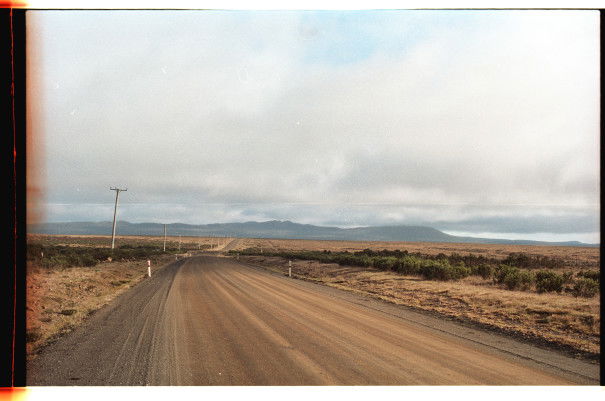

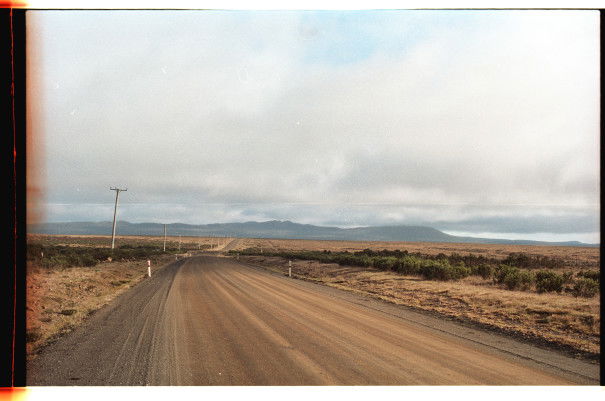

It had been twilight by the time I arrived in the highlands, driving up a narrow road that wound through rolling, grassy pasture land. Tasmania has an old-country feel; the village hotels offer Dorset teas and lorries sit by the roadside packed with Merino sheep. A poppy farmer in Bothwell had advised me not to miss this drive. By nightfall, the two-lane blacktop was quiet, the air was still and cool, and the buttonwood plains seemed to stretch for miles. It felt rugged, ethereal, a place apart.

All of a sudden, the road swarmed with little bouncing shadows. The first wallaby made an alarming pop as it bounced off my rental car. I slammed on my brakes, pulled to the roadside, and put on my flashers. The pot roast dinner that I’d picked up at a roadside takeaway shop, all sticky with gravy and mashed potatoes, spilled out on to the floor. I opened the door and walked down the road expecting to find a warm body. There was roadkill everywhere. But I found nothing. The wallaby must have bounded off.

Earlier that day, the poppy farmer in Bothwell told me his uncle ran a distillery—a hillbilly still—and I’d found him at a whitewashed horse barn, tucked away behind a row of high hedges. Pete Bignell, a graying man of Scottish descent and a long-time sheep farmer, greeted me with a hearty handshake. “There’s plenty of illegal stills about,” he said, “heaps of them about, really.”

His still, which he’d hammered out of copper and welded together, was legal. Bignell called it the Belgrove Distillery. His yard was littered with big metal canisters—he also fumigated soil for apple and strawberry farmers for a living. Behind the barn was a field of rye. It seemed like he did it all. Bignell showed me to a big, rusty washing machine, where he malted his rye, which then steeped in a big stainless steel tank that smelled of porridge. All this distilled down into a spicy, white rye. “I just do the cuts by nose,” he said. “I know what I want in there. It’s a very different way of doing things.”

As if to demonstrate the point, he got on the floor of the barn and fired up a burner, an old pool heater he’d salvaged from his “auntie” that looked like a cross between a flamethrower and a leaf-blower. It ran off used cooking-oil and sent up a faint smell of fish n’ chips. Before I left, I picked up a couple sixty-milliliter sampler bottles, thinking I’d try them once I returned home.

Late that night, I decided to take an early return on my investments, as I rinsed the blood off the plastic bumper. The first sip of uncle Pete’s rye was spicy. It burned, but it did the trick. The next morning, a bright, spring day, the bottle was empty and, when I peered under the bumper—a faint throbbing in my temples—I saw only a flyspeck of fur.