A Drink With No Country

A Drink With No Country

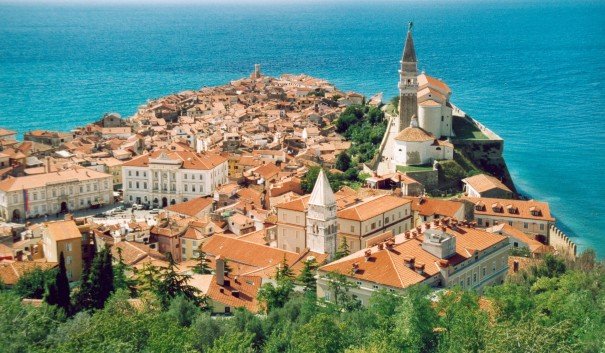

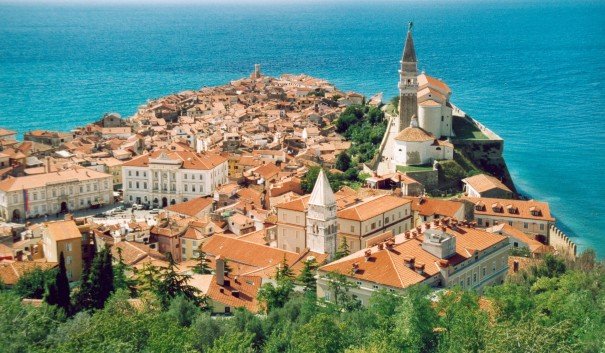

Hugos in Piran

The street that slopes towards the sea is called Via Karl Marx. A little further back, behind the red Venetian house and leonine Venetian statues and the Hapsburg silkiness of Tartini Square, is the cobblestoned Via Engels. The street’s official name—Engelsova Ulica—is also given, but here, just beyond an Italo-Slovene border that, for many locals, is just a suggestion, Italian is the language of tourism. Here, overlooking the blue water, is the Café Theatre: an art nouveau theater that has been converted into a cocktail bar. Lautrec-style paintings of “Gaiety Girls” in corseted bustles line one wall, waterfront windows the other.

Next door, the terrace of Hotel Piran—est. 1913, the sign reminds me—spills out towards the water. It is the sort of hotel you find in midcentury novels, one of the melancholy, French-style grands hôtels. They exist less on the land on which they stand than in an atemporal communion with all others: the Baron in Aleppo, the Pera Palace in Istanbul. Waiters are formal, floors are marble, old women linger. Centuries, like borders, do not exist.

And we all drink Hugos.

Hugos, in all the culturally indeterminate cities of the Adriatic Coast, are a cocktail without a country. I first drank them in front of the Verdi Theatre in Trieste, where an acquaintance explained to me a folk etymology that is in all likelihood entirely wrong. “It’s pronounced Ugo,” she said. “Ugo – as in Yugoslavia.” After all, she says, Trieste was once—according to Churchill’s famous speech—the terminal rail of the Iron Curtain: everything after it was east.

Except that it is popular, too, in the South Tyrol and in what was once Austria-Hungary. It is the Germanic alpine elderflower that gives the drink—an effervescent and variant mixture of elderflower, mint, champagne, sparkling water, and lime—its signature fragrance. It is like an Austrian Spritz (this part of the Adriatic, after all, was once part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire) but it is not. It also shares similarities with the Venetian variety—Venice, too, held sway here—but is not that, either. In Trieste, it is paired with Liptauer Condito: an anchovy and sheep-cheese paste spread over rough, Central European rye. In Groznjan, Croatia, an artists’ hill town of woven stone a twenty-minute drive away, it might be paired with truffled cheese.

In Piran, I drink it after a plate of fresh-fried squid, ordered from a vine-covered counter in the Piazza Vecchia, overlooking the eighteen-year-old century cistern and consumed on my walk back to the hotel. It is sweeter here than in Trieste—less elderflower, more lime—and colder.

I am in Slovenia, or else I am in former-Venice, or former-Austria-Hungary, or else in former-Yugoslavia, or else—if I believe the separatist claims of the Trieste Liberà Movement—in an occupied portion of the Free State of Trieste, which they argue ought to contain all of the Istrian Peninsula: Croatia, Italy, and Slovenia alike.

Either way, I drink my Hugo.

Either way, all around me, the sun dives into blackness, and I do not want to be anywhere else.